Abstract

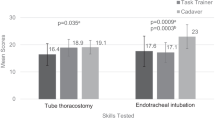

Emergency medicine (EM) training mandates that residents be able to competently perform low-frequency critical procedures upon graduation. Simulation is the main method of training in addition to clinical patient care. Access to cadaver-based training is limited due to cost and availability. The relative fidelity and perceived value of cadaver-based simulation training is unknown. This pilot study sought to describe the relative value of cadaver training compared to simulation for cricothyrotomy and tube thoracostomy. To perform a pilot study to assess whether there is a significant difference in fidelity and educational experience of cadaver-based training compared to simulation training. To understand how important this difference is in training residents in low-frequency procedures. Twenty-two senior EM residents (PGY3 and 4) who had completed standard simulation training on cricothyrotomy and tube thoracostomy participated in a formalin-fixed cadaver training program. Participants were surveyed on the relative fidelity of the training using a 100 point visual analogue scale (VAS) with 100 defined as equal to performing the procedure on a real patient. Respondents were also asked to estimate how much the cadaveric training improved the comfort level with performing the procedures on a scale between 0 and 100 %. Open-response feedback was also collected. The response rate was 100 % (22/22). The average fidelity of the cadaver versus simulation training was 79.9 ± 7.0 vs. 34.7 ± 13.4 for cricothyrotomy (p < 0.0001) and 86 ± 8.6 vs. 38.4 ± 19.3 for tube thoracostomy (p < 0.0001). Improvement in comfort levels performing procedures after the cadaveric training was rated as 78.5 ± 13.3 for tube thoracostomy and 78.7 ± 14.3 for cricothyrotomy. All respondents felt this difference in fidelity to be important for procedural training with 21/22 respondents specifically citing the importance of superior landmark and tissue fidelity compared to simulation training. Cadaver-based training provides superior landmark and tissue fidelity compared to simulation training and may be a valuable addition to EM residency training for certain low-frequency procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baker K (2011) Determining resident clinical performance: getting beyond the noise. Anesthesiology 115(4):862–878. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e318229a27d

King RW, Schiavone F, Counselman FL, Panacek EA. Patient care competency in emergency medicine graduate medical education: Results of a consensus group on patient care. In: Academic Emergency Medicine.Vol 9.; 2002:1227-1235. doi:10.1197/aemj.9.11.1227

Wang EE, Quinones J, Fitch MT et al (2008) Developing technical expertise in emergency medicine—the role of simulation in procedural skill acquisition. Acad Emerg Med 15:1046–1057. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00218.x

Mayo PH, Hackney JE, Mueck JT, Ribaudo V, Schneider RF (2004) Achieving house staff competence in emergency airway management: results of a teaching program using a computerized patient simulator. Crit Care Med 32(12):2422–2427. pii:00003246-200412000-00009

Charlton R, Dovey SM, Jones DG, Blunt A (1994) Effects of cadaver dissection on the attitudes of medical students. Med Educ 28:290–295. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.1994.tb02714.x

Hafferty FW (1988) Cadaver stories and the emotional socialization of medical students. J Health Soc Behav 29:344–356. doi:10.2307/2136868

Ferrada P, Anand RJ, Amendola M, Kaplan B (2014) Cadaver laboratory as a useful tool for resident training. Am Surg 80:408–409. http://search.proquest.com/openview/f12a36552598cbbb4f84a49f5dffd981/1?pq-origsite=gscholar. Accessed 23 Mar 2016

Sharma M, Macafee D, Horgan AF (2013) Basic laparoscopic skills training using fresh frozen cadaver: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Surg 206:23–31. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.10.037

Dawson DL, Meyer J, Lee ES, Pevec WC (2007) Training with simulation improves residents’ endovascular procedure skills. J Vasc Surg 45:149–154. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.09.003

Anastakis DJ, Regehr G, Reznick RK, et al. (1999) Assessment of technical skills transfer from the bench training model to the human model. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00327-4

Eyre A, Eicken J (2014) TITUS–making chest tube thoracostomy training realistic, efficient, and affordable. Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD) Annual Meeting

Langdorf MI, Montague BJ, Bearie B, Sobel CS (1998) Quantification of procedures and resuscitations in an emergency medicine residency. J Emerg Med 16:121–127. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(97)00252-7

Lewis CE, Peacock WJ, Tillou A, Hines OJ, Hiatt JR (2012) A novel cadaver-based educational program in general surgery training. J Surg Educ 69:693–698. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2012.06.013

Ocel JJ, Natt N, Tiegs RD, Arora AS (2006) Formal procedural skills training using a fresh frozen cadaver model: a pilot study. Clin Anat 19:142–146. doi:10.1002/ca.20166

Tabas JA, Rosenson J, Price DD, Rohde D, Baird CH, Dhillon N (2005) A comprehensive, unembalmed cadaver-based course in advanced emergency procedures for medical students. Acad Emerg Med 12:782–785. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.004

Sagarin MJ, Barton ED, Chng YM, Walls RM (2005) Airway management by US and Canadian emergency medicine residents: a multicenter analysis of more than 6000 endotracheal intubation attempts. Ann Emerg Med 46:328–336. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.009

Sethuraman KN, Duong D, Mehta S et al (2011) Complications of tube thoracostomy placement in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 40:14–20. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.06.033

Al-Eissa M, Chu S, Lynch T, et al. (2008) Self-reported experience and competence in core procedures among Canadian pediatric emergency medicine fellowship trainees. CJEM 10(6):533–538. pii:fab8057485954c3ab3bc0dc3785b737d

Ball CG, Lord J, Laupland KB, et al. (2007) Chest tube complications: how well are we training our residents? Can J Surg 50(6):450–458. http://search.proquest.com/openview/a2ff2f29d795ebd7025f202e219e53fc/1?pq-origsite=gscholar. Accessed 23 Mar 2016

Leblanc F, Champagne BJ, Augestad KM et al (2010) A comparison of human cadaver and augmented reality simulator models for straight laparoscopic colorectal skills acquisition training. J Am Coll Surg 211:250–255. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.04.002

Sharma M, Horgan A (2012) Comparison of fresh-frozen cadaver and high-fidelity virtual reality simulator as methods of laparoscopic training. World J Surg 36:1732–1737. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1564-6

McCarthy MC, Ranzinger MR, Nolan DJ, Lambert CS, Castillo MH (2002) Accuracy of cricothyroidotomy performed in canine and human cadaver models during surgical skills training. J Am Coll Surg 195:627–629. doi:10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01337-6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Takayesu, J.K., Peak, D. & Stearns, D. Cadaver-based training is superior to simulation training for cricothyrotomy and tube thoracostomy. Intern Emerg Med 12, 99–102 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-016-1439-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-016-1439-1