Abstract

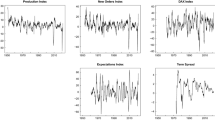

In this paper we apply wavelet analysis to study the dynamics of long-term movements in wholesale prices for the USA, the UK and France over the period 1791–2012. The application of wavelet analysis to long-term historical price series allows us to detect long waves in prices whose periodization is remarkably similar to those provided in the literature for the pre-World War II period. Moreover, we find evidence on the existence of long waves in prices also after World War II, a period in which long waves are generally difficult to detect because of the positive trend displayed by prices. The comparison between the long wave components extracted through wavelets and the Christiano–Fitzgerald band-pass filter suggests that wavelets provide a reliable and straightforward technique for analyzing long waves dynamics in time series exhibiting quite complex patterns such as historical data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the classical decomposition approach time series are the sum of different unobserved components: trend, cyclical, seasonal and irregular components.

Growth cycles definition follows from the modern approach to business cycles analysis (Lucas 1977), where business cycles are defined as fluctuations around a (stochastic) trend.

Although designed using frequency domain analysis, these filters are undertaken in the time domain by applying moving averages to time series data.

In this study we do not intend to provide a solution to the problem of the statistical proof of Kondratieff cycles. The statistical identification of long waves is at least problematic given the low number of repeated cycles within the period of observation, i.e., the Kondratieff cycle is too long for the length of the present time series.

The gain and the phase shift of the filter determine the so-called transfer function of a filter which is used to evaluate the properties of a filter.

However, the ideal band-pass filter requires the application of an infinite-order moving average filter to the series of interest, and thus, some kind of approximation is needed in order to be implemented in empirical applications.

The theory of the spectral analysis relies on the spectral representation theorem according to which any time series within a broad class can be decomposed into different frequency components.

The signal can then be analyzed for its frequency content because the Fourier coefficients of the transformed function represent the contribution of each sine and cosine function at each frequency.

In additon, the results of the frequency domain method at all dates are dependent on the sample length (Baxter and King 1999).

Nonstationarity is an intrinsic feature of datasets used in long waves studies since long-term data generally include historical events such as war episodes, policy changes, technique innovations and crisis periods that are likely to be responsible for structural breaks in the form of abrupt changes, jumps and volatility clustering.

Detrending procedures are not neutral with respect to the results relating to the existence of cycles: “the smoothing techniques may create artefacts” (Freeman and Louçã 2001, p. 99).

The exact band-pass filter is a moving average of infinite order, so an approximation is necessary for practical application.

The ideal band-pass filter can be better approximated with longer moving averages. Using a larger number of leads and lags allows for a better approximation of the exact band-pass filter, but makes unusable more observations at the beginning and end of the sample.

Wavelets, their generation and their potential usefulness are discussed in intuitive terms in Ramsey (2010, 2014). A more technical exposition with many examples of the use of wavelets in a variety of fields is provided by Percival and Walden (2000), while an excellent introduction to wavelet analysis along with many interesting economic and financial examples is given in Gençay et al. (2002) and Crowley (2007).

Moreover, the transformation to the frequency domain does not preserve the time information so that it is impossible to determine when a particular event took place, a feature that may be important in the analysis of economic relationships. In other words, it has only frequency resolution but not time resolution.

Corrections for war periods (war data are influenced by pre-war armament booms, war economy and post-war reconstruction booms around World War II and to a lesser extent World War I) are generally applied to original data by interpolating series for the war years (Metz 1992) or a priori elimination of the impact of the war periods (Korotayev and Tsirel 2010) on the assumption that such shocks can be seen as disturbances in the normal structure of data.

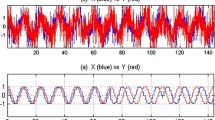

Each of the sets of the coefficients \(s_{J},d_{J},d_{J-1},\ldots ,d_{1}\) is called a crystal in wavelet terminology.

They capture oscillations with a period of 2–4, 4–8, 8–16, 16–32 and 32–64 years, respectively.

The variance of the time series is preserved in the variance of the coefficients from the MODWT, i.e., \(\hbox {var}(X_{t}) = \sum _{j=1}^J \hbox{var}(d_{j},t) + \hbox{var}(s_{J},t)\) (see Percival and Mojfeld 1997).

Data from 1791 to 1990 are taken from Lothian and Taylor (1996). As stated in their Appendix (see pp. 505–506), the origin of the wholesale prices series is as follows. For France: 1803–1948, European Historical Statistics (Mitchell 1975, pp. 772–774, table 1) and 1949–1990, various issues of International Financial Statistics (IFS). For the UK: 1791–1939, 1946–1948, Jastram (1977, pp. 32–33, table 2), 1939–1945, Board of Trade, wholesale price index for 1930–1950, as reported in British Historical Statistics (p. 730), table entitled Prices 5, and 1948–1990, IFS, various issues. For the USA 1791–1800, Warren and Pearson (1935, pp. 30–32, table 1), 1800–1976, Jastram (1977, pp. 145–146, table 7), 1976–1990, IFS, various issues. From 1991 to 2012 wholesale price series for the three countries are updated by the authors using various issues of IFS.

The breakpoints are estimated with the R package strucchange (Zeileis et al. 2002). The number of estimated breakpoints according to the values of the RSS and BIC criteria are five and four, respectively. However, on the grounds of sequential tests and also because of the well-known fact that information criteria are often downward biased, we select three breaks (Bai and Perron 2003).

Although wavelets were first introduced in the mid-80s and the real development started in the early 90s, they are considered a relatively new tool in signal processing. Nonetheless, in the last decades, they are becoming increasingly popular, especially in economics and finance applications.

We apply the MOWDT because the DWT has two main drawbacks: (1) the dyadic length requirement (i.e., a sample size divisible by \(2^{J}\)), (2) the wavelet and scaling coefficients are not shift invariant, and, finally, the MODWT produces the same number of wavelet and scaling coefficients at each decomposition level as it does not use downsampling by two.

With reflecting boundary conditions, the original signal is reflected about its end point to produce a series of length 2N which has the same mean and variance as the original signal.

See Bernard et al. (2014) for a discussion of the main theories of long waves proposed in the literature and for some empirical evaluation of the empirical evidence on cycles of different time scales.

Indeed, most economic variables display a spectrum that exhibit a smooth declining shape with considerable power at very low frequencies.

This last result strictly holds for the UK and the USA, whereas in the case of France the level of energy at the \(D_{4}\) level is slightly higher than that at the \(D_{5}\) level.

According to Lewis (1978) Kondratieff price swings, which is declining prices from 1873 to 1895 followed by rising prices from 1895 to 1913, are associated with a change in the terms of trade between agriculture and industry, where agricultural prices fall more up to 1895 and then rise relative to industrial prices.

Indeed, the diverging pattern emerging in the first decade of the new millennium indicates that a phase shift between the price waves of the USA and those of the two European countries could have occurred.

We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting this point.

After Kondratieff (1926) a huge number of long wave chronologies have been proposed by various authors, e.g., Schumpeter (1939), Clark (1944), Burns and Mitchell (1946), Dupriez (1951), Imbert (1959), Mandel (1975), Rostow (1978), van Duijn (1983), among the others, but only a few of them are based on nominal prices.

In Kondratieff the peak of the third long cycle for France is located in 1920 because Kondratieff’s periodization is based upon the movement of gold prices, not nominal prices.

We select the band-pass filtered frequency components in the BK and CF filters so that only fluctuations within the band of 32–64 years are retained in each filtered component.

The BK filter is estimated using a value of leads and lags equal to 12 and padding the original data at both sides to compensate for the loss of data. The filtered components detected using the BK filter (not reported in Fig. 4) are strikingly different from the two other filters, both as to the amplitude of the movements and the timing of the turning points.

These results are fully in line with a-priori expectations about the ability of band-pass filters to extract the cyclical component whose performance are likely to depend on the characteristics of the spectral density of the (unknown) theoretical cyclical component (e.g., Metz 2011). The filters by Baxter and King (1999) and Christiano and Fitzgerald (2003) assume a special type of data generating process, that is independent and identically distributed variables and random walks, respectively. Since a random walk puts more weight on lower frequencies, whereas independent and identically distributed variables weight all frequencies equally, Everts (2006, p.17) conclude that “the filter by Christiano and Fitzgerald approximates the ideal band-pass filter for data sets with low frequencies (long durations) better than the filter by Baxter and King” and that “produces more accurate results for long business cycles than the one by Baxter and King.” On the other hand the filter by Baxter and King approximates the ideal band-pass filter for shorter business cycles with higher accuracy than the filter by Christiano and Fitzgerald which provide a worse performance for cycles with short durations.

As evidenced by Metz (2009, p. 65), “the mechanical use of filters without considering trend breaks may result in spurious impression of the trend and cyclical behavior of time series.”

Filtering methods applied to a finite length time series inevitably suffer from border distortions; this is due to the fact that the values of the transform at the beginning and the end of the time series are always incorrectly computed, in the sense that they involve missing values of the series which are then artificially prescribed. Therefore, at the edges of a series the filtered values are likely to suffer from these boundary effects and have to be interpreted carefully.

References

Andrews DWK, Lee I, Ploberger W (1996) Optimal change-point tests for normal linear regression. J Econom 70:9–38

Bai J (1994) Least squares estimation of a shift in linear processes. J Time Ser Anal 15:453–472

Bai J (1997a) Estimating multiple breaks one at a time. Econom Theory 13:315–352

Bai J (1997b) Estimation of a change point in multiple regression models. Rev Econ Stat 79:551–563

Bai J, Perron P (1998) Estimating and testing linear models with multiple structural changes. Econometrica 66:47–78

Bai J, Perron P (2003) Computation and analysis of multiple structural change models. J Appl Econom 18:1–22

Baxter M (1994) Real exchange rates and real interest differentials: have we missed the business-cycle relationship? J Monet Econ 33:5–37

Baxter M, King R (1999) Measuring business cycles: approximate band-pass filters for economic time series. Rev Econ Stat 81:575–593

Bernard L, Gevorkyan A, Palley T, Semmler W (2014) Time scales and mechanisms of economic cycles: a review of theories of long waves. Rev Keynes Econ 2:87–107

Berry BJL (2006) Recurrent instabilities in K-wave macrohistory. In: Devezas TC (ed) Kondratieff waves, warfare and world security. IOS Press, Amsterdam, pp 22–29

Berry BJL, Kim H, Kim H-M (1993) Are long waves driven by techno-economic transformations? Technol Forecast Soc Change 44:111–135

Bieshaar H, Kleinknecht A (1984) Kondratieff long waves in aggregate output? an econometric test. Konjunkturpolitik 30:279–303

Bosserelle E (1991) Les fluctuations longues de prix de type Kondratieff. Thèse de doctorat nouveau régime en sciences économiques, Université de Reims

Bosserelle E (2001) Le cycle Kondratieff : mythe ou réalité? Futuribles International, numéro 16, LIPS, DATAR, Commissariat Général du Plan

Bosserelle E (2012) La croissance économique dans le long terme: S. Kuznets versus N.D. Kondratiev - Actualité d’une controverse apparue dans l’entre-deux-guerres. Economies et Sociétés, Cahiers de l’ISMEA, série Histoire économique quantitative, AF, 45:1655–1688

Bosserelle E (2013) Les études empiriques menées sur les cycles longs depuis le début des années 1980: Quels enseignements? In: Diemer A, Borodak D, Dozolme S (eds). Heurs et malheurs du capitalisme, Editions Oeconomia, pp 132–154

Bossier F, Hugé P (1981) Une vérification empirique de l’existence de cycles longs á partir de données belges. Cahiers économiques de Bruxelles 90:253–267

Burns AF, Mitchell WC (1946) Cyclical changes in cyclical behavior. In: Burns AF, Mitchell WC (eds) Measuring business cycles. NBER, New York, pp 424–471

Christiano LJ, Fitzgerald TJ (2003) The band pass filter. Int Econ Rev 44(2):435–465

Clark C (1944) The economics of 1960. MacMillan, London

Crowley P (2007) A guide to wavelets for economists. J Econ Surv 21:207–267

Darné O, Diebolt C (2004) Unit roots and infrequent large shocks: new international evidence on output. J Monet Econ 51:1449–1465

Daubechies I (1992) Ten lectures on wavelets. In: CBSM-NSF regional conference series in applied mathematics, vol 61. SIAM, Philadelphia

de Wolff S (1924) Prosperitats-und Depressionsperioden. In: Jensen O (ed) Der Lebendige Marxismus. Thuringer Verlagsanstalt, Jena, pp 13–43

Diebolt C (2005) Long cycles revisited—an essay in econometric history. Economies et Sociétés, série Histoire économique quantitative AF 32:23–47

Diebolt C, Doliger C (2006) Economic cycles under test: a spectral analysis. In: Devezas TC (ed) Kondratieff waves, warfare and world security. IOS Press, Amsterdam, pp 39–47

Diebolt C, Doliger C (2007) Retour sur la périodicité d’une nébuleuse: le cycle économique. Réponse à Eric Bosserelle. Economie Appliquée 50:199–204

Diebolt C, Doliger C (2008) New international evidence on the cyclical behaviour of output: Kuznets swings reconsidered. Quality and quantity. Int J Methodol 42:719–737

Dupriez LH (1951) Des mouvements économiques généraux, Tomes 1 et 2. Edition Nauwelaerts, Louvain

Englund P, Persson T, Svensson L (1992) Swedish business cycles: 1861–1988. J Monet Econ 30:343–371

Erten B, Ocampo JA (2013) Super cycles of commodity prices since the mid nineteenth century. World Dev 44:14–30

Everts M (2006) Band-pass filters. Munich Personal RePec Archive Paper no. 2049

Freeman C, Louçã F (2001) As time goes by: from the industrial revolution to the information revolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gençay R, Selçuk F, Whitcher B (2002) An introduction to wavelets and other filtering methods in finance and economics. San Diego Academic Press, San Diego

Gençay R, Gradojevic N, Selçuk F, Whitcher B (2010) Asymmetry of information flow between volatilities across time scales. Quant Finance 10:895–915

Gerster HJ (1988) Lange Wellen wirtschaftlicher Entwicklung. Lang, Frankfurt

Gerster HJ (1992) Testing long waves in price and volume series from Sixteen Countries. In: Kleinknecht A, Mandel E, Wallerstein I (eds) New findings in long wave research. St Martin’s Press, New York, pp 120–147

Goldstein JS (1988) Long cycles: prosperity and war in the modern age. Yale University Press, New Haven

Goldstein JP (1999) The existence, endogeneity and synchronization of long waves: structural time series model estimates. Rev Radic Polit Econ 31:61–101

Granger WJ (1961) The typical spectral shape of an economic variable. Econometrica 34:150–161

Hassler J, Lundvik P, Persson T, Söderlind P (1994) The Swedish business cycle: stylized facts over 130 years. In: Bergstrom V, Vredin A (eds) Measuring and interpreting business cycles. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp 11–108

Haustein HD, Neuwirth E (1982) Long waves in world industrial production, energy consumption, innovations, inventions, and patents and their identification by spectral analysis. Technol Forecast Soc Change 22:53–89

Imbert G (1959) Des mouvements de longue durée Kondratieff. Thèse, Aix. La pensée universitaire, 1960

Jacks DS (2013) From boom to bust: a typology of real commodity prices in the long run. NBER, WP no. 18874

Jerrett D, Cuddington JT (2008) Broadening the statistical search for metal price super cycles to steel and related metals. Resour Policy 33:188–195

Kondratieff ND (1926) The major cycles of the conjuncture and the theory of forecast. Economika, Moscow

Kondratieff ND (1935) The long waves in economic life. Rev Econ Stat 17:105–115

Kondratieff ND (1992) Les grands cycles de la conjoncture. Economica, Paris

Korotayev AV, Tsirel SV (2010) A spectral analysis of world GDP dynamics: Kondratieff waves, Kuznets swings, Juglar and Kitchin cycles in global economic development, and the 2008–2009 economic crisis. Struct Dyn 4:3–57

Kriedel N (2009) Long waves of economic development and the diffusion of general-purpose technologies: the case of railway networks. Economies et Sociétés, série Histoire économique quantitative, AF 40:877–900

Kuczynski T (1978) Spectral analysis and cluster analysis as mathematical methods for the periodization of historical processes. Kondratieff cycles—appearance or reality? In: Proceedings of the seventh international economic history congress, vol 2. International Economic History Congress, Edinburgh, pp 79–86

Lewis WA (1978) Growth and fluctuations 1870–1913. George Allen and Unwin, London

Lothian JR, Taylor MP (1996) Real exchange rate behavior: the recent float from the perspective of the past two centuries. J Polit Econ 104:488–509

Lucas RE (1977) Understanding business cycles. Carnegie-Rochester Conf Ser Public Policy 5:7–29

Mandel E (1975) Long waves in the history of capitalism. In: Review NL (ed) Late capitalism. NLB, London, pp 108–146

Metz R (1992) A Re-examination of long waves in aggregate production series. In: Kleinknecht A, Mandel E, Wallerstein I (eds) New findings in long waves research. St. Martin’s Press, New York, pp 80–119

Metz R (2006) Empirical evidence and causation of Kondratieff cycles. In: Devezas TC (ed) Kondratieff waves, warfare and world security. IOS Press, Amsterdam, pp 91–99

Metz R (2009) Comment on Stock markets and business cycle comovement in Germany before world war I: evidence from spectral analysis. J Macroecon 31:58–67

Metz R (2011) Do Kondratieff waves exist? How time series techniques can help to solve the problem. Cliometrica 5:205–238

Metz R, Stier W (1992) Modelling the long wave-phenomena. Hist Soc Res 17:43–62

Mosekilde E, Rasmussen S (1989) Empirical indication of economic long waves in aggregate production. Eur J Oper Res 42:279–293

Percival DB, Mojfeld H (1997) Analysis of subtidal coastal sea level fluctuations using wavelets. J Am Stat Assoc 92:868–880

Percival DB, Walden AT (2000) Wavelet methods for time series analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Proietti T (2011) Trend estimation. In: Lovric M (ed) International encyclopedia of statistical science, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin

Ramsey JB (2010) Wavelets. In: Durlauf SN, Blume LE (eds) The new Palgrave dictionary of economics. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp 391–398

Ramsey JB (2014) Functional representation, approximation, bases and wavelets. In: Marco Gallegati, Semmler W (eds) Wavelet applications in economics and finance. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 1–20

Ramsey JB, Zhang Z (1995) The analysis of foreign exchange data using waveform dictionaries. J Empir Finance 4:341–372

Ramsey JB, Zhang Z (1996) The application of waveform dictionaries to stock market index data. In: Kravtsov YA, Kadtke J (eds) Predictability of complex dynamical systems. Springer, Berlin, pp 189–208

Reijnders JPG (1990) Long waves in economic development. Edward Elgar, Aldershot

Rostow WW (1978) The world economy: history and prospect. University of Texas Press, Austin

Schumpeter JA (1939) Business cycles. McGraw-Hill, New York

Solomou S (1990) Phases of economic growth 1850–1973. Kondratieff waves and Kuznets swings. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Stier W (1989) Basic concepts and new methods of time series analysis. Hist Soc Res 14:3–24

Strang G (1993) Wavelet transforms versus Fourier transforms. Bull Am Math Soc 28:288–305

Taylor JB (1988) Long waves in six nations: results and speculations from a new methodology. Review 9:373–392

van Duijn JJ (1979) The long wave in economic life. Economist 125:544–576

van Duijn JJ (1983) The long wave in economic life. Allen and Unwin, Boston

van Ewijk C (1981) The long wave–a real phenomenon? Economist 129:324–372

van Ewijk C (1982) A spectral analysis of the Kondratieff cycle. Kyklos 35:468–499

van Gelderen J (1913) Springvloed: Beschouwingen over industrieele ontwikkeling en prijsbeweging (Spring Tides of Industrial Development and Price Movements), De Nieuwe Tijd 18:253–277, 369–384, 445–464

Zarnowitz V, Ozyildirim A (2002) Time Series decomposition and measurement of business cycles. Trends and growth cycles. NBER Working Paper no. 8736, Cambridge

Zeileis A, Leisch F, Hornik H, Kleiber C (2002) strucchange: An R package for testing for structural change in linear regression models. J Stat Softw 7:1–38

Acknowledgments

A preliminary version of the paper has been presented at the 16th Conference of the Association for Heterodox Economics, University of Greenwich, London, Uk, 2–4 July 2014. We thank participant for their useful comments. We would like to thank three anonymous reviewers whose careful reading and valuable comments considerably improved our original text. The responsibility for all remaining errors is, of course, ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallegati, M., Gallegati, M., Ramsey, J.B. et al. Long waves in prices: new evidence from wavelet analysis. Cliometrica 11, 127–151 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-015-0137-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-015-0137-y