Abstract

Background

Emotional eating (EE) has been implicated as an important variable in bariatric surgery and is frequently assessed during preoperative evaluations. Little is known about the association between preoperative EE and postoperative outcomes. This study examined associations between preoperative EE, as measured by the Weight and Lifestyle Inventory, and 2-year postoperative percent weight loss.

Methods

Data collected during preoperative evaluations were analyzed retrospectively. A total of 685 patients completed intake data, with 357 patients (52 %) completing 2-year follow-up measures. The average time from the initial appointment to surgery is 6 months. Preoperative data was collected at approximately month 2 of this 6-month period. Follow-up data was collected during 2-year postoperative follow-up visits.

Results

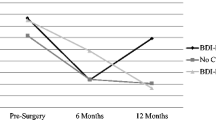

The average percent of weight lost was 22.93 (SD = 13.62). Analyses indicated that (1) EE was not associated with percent weight loss for the overall sample, (2) EE was not associated with percent weight loss for females, (3) EE in response to positive affect was associated with percent weight loss for males, and (4) the interaction between preoperative depressive symptoms and EE was not associated with percent weight loss for either sex.

Conclusion

While the WALI provides a fruitful means of gathering clinical information, results suggested no association between scores on Section H of the WALI and weight loss. The results suggest that EE may impact surgical outcomes differentially in men as compared to women. Future research should seek to replicate these findings and focus on gender differences related to surgical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ganley RM. Emotion and eating in obesity: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 1989;8:343–61.

Canetti L, Bachar E, Berry EM. Food and emotion. Behav Process. 2002;60:157–64.

Zijlstra H, van Middendorp H, Devaere L, et al. Emotion processing and regulation in women with morbid obesity who apply for bariatric surgery. Psychol Health. 2012;27:1375–87.

Walfish S. Self-assessed emotional factors contributing to increased weight gain in pre-surgical bariatric patients. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1402–5.

Walfish S, Brown TA. Self-assessed emotional factors contributing to increased weight in presurgical male bariatric patients. Bariatr Nurs Surg Patient Care. 2009;4:49–52.

Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, et al. Self-reported eating behaviors of extremely obese persons seeking bariatric surgery: a factor analytic approach. Obesity. 2006;14:83S–9S.

Dziurowicz-Kozlowska AH, Wierzbicki Z, Lisik W, et al. The objective of psychological evaluation in the process of qualifying candidates for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:196–202.

Litwin R, Goldbacher EM, Cardaciotto L, et al. Negative emotions and emotional eating: the mediating role of experiential avoidance. Eat Weight Disord; Forthcoming 2016.

Bongers P, Jansen A, Havermans R, et al. Happy eating. The underestimated role of overeating in a positive mood. Appetite. 2013;67:74–80.

Dawes AJ, Maggard-Gibbons M, Maher AR, et al. Mental health conditions among patients seeking and undergoing bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2016;315:150–63.

Bhatti JA, Nathens AB, Thiruchelvam D, et al. Self-harm emergencies after bariatric surgery: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(3):226–32.

Conason A, Teixeira J, Hsu C, et al. Substance use following bariatric weight loss surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:145–50.

Wallis DJ, Hetherington MM. Stress and eating: the effects of ego-threat and cognitive demands on food intake in restrained and emotional eaters. Appetite. 2004;43:39–46.

Sarwer DB, Allison KC, Bailer B, Faulconbridge LF, Wadden TA. Bariatric surgery. In: Block AR, Sarwer DB, editors. Presurgical psychological screening: understanding patients, improving outcomes. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. p. 61–83.

Wedin S, Madan A, Correll J, et al. Emotional eating, marital status and history of physical abuse predict 2-year weight loss in weight loss surgery patients. Eat Behav. 2014;15:619–24.

Canetti L, Berry EM, Elizur Y. Psychosocial predictors of weight loss and psychological adjustment following bariatric surgery and a weight-loss program: the mediating role of EE. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:109–17.

Fuchs HF, Broderick RC, Harnsberger CR, et al. Benefits of bariatric surgery do not reach obese men. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2015;25:196–201.

Mahony D. Psychological gender differences in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2008;18:607–10.

Wadden TA, Foster GD. The weight and lifestyle inventory (WALI). Obesity. 2006;14:99S–118S.

Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Sarwer DB, et al. Comparison of psychosocial status in treatment-seeking women with class III vs. class I-II obesity. Obesity. 2006;14:90S–8S.

Wadden TA, Sarwer DB. Behavioral assessment of candidates for bariatric surgery: a patient-oriented approach. Obesity. 2006;14:53S–62S.

Gelinas BL, Delparte CA, Wright KD, et al. Problematic eating behavior among bariatric surgical candidates: a psychometric investigation and factor analytic approach. Eat Behav. 2015;16:34–9.

Larsen JK, van Strien T, Eisinga R, et al. Gender differences in the association between alexithymia and emotional eating in obese individuals. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:237–43.

van Strien T, Levitan RD, Engels RCME, et al. Season of birth, the dopamine D4 receptor gene and emotional eating in males and females. Evidence of a genetic plasticity factor? Appetite. 2015;90:51–7.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) manual. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993.

Larsen JK, Geenen R, Maas C, et al. Personality as a predictor of weight loss maintenance after surgery for morbid obesity. Obes Res. 2004;12:1828–34.

Rosik CH. Psychiatric symptoms among prospective bariatric surgery patients: rates of prevalence and their relation to social desirability, pursuit of surgery, and follow-up attendance. Obesity. 2005;15:677–83.

Ambwani S, Boeka AG, Brown JD, et al. Socially desirable responding by bariatric surgery candidates during psychological assessment. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:300–5.

Corsica JA, Azarbad L, McGill K, Wool L, Hood M. The Personality Assessment Inventory: clinical utility, psychometric properties, and normative data for bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2010;20:722–31.

Koenders PG, van Strein T. Emotional eating, rather than lifestyle behavior, drives weight gain in a prospective study in 1562 employees. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53:1287–93.

Brogan A, Hevey D. Eating styles in the morbidly obese: restraint eating, but not emotional and external eating, predicts dietary behavior. Psychol Health. 2013;28:714–25.

Patel KA, Schlundt DG. Impact of moods and social context on eating behavior. Appetite. 2001;36(2):111–8.

Turner SA, Luszczynska A, et al. Emotional and uncontrolled eating styles and chocolate chip cookie consumption. A controlled trial of the effects of positive mood enhancement. Appetite. 2010;54(1):143–9.

Martin M, Beekley A, Kjorstad R, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in eligibility and access to bariatric surgery: a national population-based analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:8–15.

Fuchs HF, Broderick RC, Harnsberger CR, et al. Benefits of bariatric surgery do not reach obese men. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25(3):196–201.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fink-Miller, E., Rigby, A. The Utility of the Weight and Lifestyle Inventory (WALI) in Predicting 2-Year Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery. OBES SURG 27, 933–939 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2385-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2385-8