“When walking in quicksand country, carry a stout pole — it will help you get out should you need to. As soon as you start to sink, lay the pole on the surface of the quicksand. Flop onto your back on top of the pole. Work the pole to a new position: under your hips and at right angles to your spine. Take the shortest route to firmer ground, moving slowly.”

Piven/Borgenicht 1999, p. 18

Summary

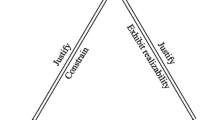

The paper focuses upon curriculum planning in the scientific disciplines at university level, although it is claimed the argument may be of wider applicability. Drawing upon the writings of philosophers of education from several decades ago (notably Schwab and Scheffler) whose work is too often overlooked in contemporary debates about the curriculum, and using illustrative examples from the author’s own experience, it is argued that too often the focus of science curriculum planning is the “rhetoric of conclusions” or the “substantive structure” — the current state of knowledge at the forefront of the respective disciplines — to the neglect of what Schwab called the “syntactical structure” of the sciences (which roughly approximates their epistemology). This aspect of these disciplines is essential for the general student trying to become familiar with the nature of science as a broad field of knowledge, for prospective teachers, and — contra Scheffler’s view — for students who aim at careers as researchers.

Zusammenfassung

Der Beitrag der Epistemologie zur Curriuculumkonstruktion in den Naturwissenschaften

Der Aufsatz fokussiert auf die Curriculumplanung für den naturwissenschaftlichen Unterricht in der universitären Lehrerausbildung, wenngleich behauptet wird, dass dieses Argument weitreichendere Anwendbarkeit besitzt. Der Text knüpft an erziehungswissenschaftlichen Schriften (insbesondere von Schwab und Scheffler) an, deren Veröffentlichung zwar einige Dekaden zurückliegt, deren Beitrag in den aktuellen Debatten aber oft übersehen wird. Darüber hinaus werden einige illustrative Beispiele aus dem Erfahrungsschatz des Autors genutzt, um zu zeigen, dass der Fokus der Curriculumplanung für die Naturwissenschaften — dem augenblicklichen Wissensstand der zu berücksichtigenden Disziplinen zufolge — zu oft in einer „Rhetorik der Schlussfolgerung“ oder „substantivischen Struktur“ besteht, was dazu führt, dass das, was Schwab die „syntaktische Struktur“ der Naturwissenschaften nennt (und ihrer Epistemologie ziemlich nahe kommt), vernachlässigt wird. Dieser Aspekt jener Disziplinen ist besonders wichtig für Studierende, die allgemeinbildend vertraut werden möchten mit den Naturwissenschaften, für angehende Lehrer und — entgegen Schefflers Ansicht — für Studenten, die eine Karriere als Forscher anstreben.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Holton, G. (2002): B. F. Skinner and P. W. Bridgman: The Frustration of a Wahlverwandtschaft. In: Heidelberger, M. /Stadler, F. (Eds.) (2002): History and Philosophy of Science. — Dordrecht, pp. 335–346.

Jackson, P. W. (1992): Conceptions of curriculum and curriculum specialists. In: Jackson, P. W. (Ed.): Handbook of Research on Curriculum. — New York.

Lakatos, I. (1976): Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programs. In: Lakatos, I. /Musgrave, A. (Eds.): Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. — Cambridge, pp. 91–196.

NRC (2002): Scientific Research in Education. — Washington, D.C.

Phillips, D. C. (1987): Philosophy, Science, and Social Inquiry. — Oxford.

Phillips, D. C. (1996): Philosophical perspectives. In: Berliner, D. /Calfee, R. (Eds.): Handbook of Educational Psychology. — New York, pp. 1005–1019.

Phillips, D. C. (2000): The Expanded Social Scientist’s Bestiary. — Lanham.

PISA (2001): Knowledge and Skills for Life: First Results from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2000. — Paris: OECD.

Piven, J. /Borgenicht, D. (1999): The Worst-Case Scenario Survival Handbook. — San Francisco.

Rennie, J. (2002): Fifteen Answers to Creationist Nonsense. In: Scientific American, Vol. 287, No. 1, pp. 78–85.

Russell, B. (1948): An Outline of Philosophy. — London 1948.

Scheffler, I. (1973): Philosophy and the curriculum. In: Scheffler, I. (Ed.): Reason and Teaching. — London, pp. 31–41.

Schwab, J. J. (1978): Science, Curriculum, and Liberal Education: Selected Essays. — Chicago.

Science and Education (1998): Special Issue: The Nature of Science and Science Education, Vol. 7, No. 6.

Shulman, L. (1987): Knowledge and teaching: foundations of the new reform. In: Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 1–22.

Skinner, B. F. (1972): Beyond Freedom and Dignity. — London.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper was presented at the conference Silence Between the Disciplines, Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, Berlin, October 2002.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Phillips, D.C. The contribution of epistemology to curriculum construction in the sciences. ZfE 6, 421–431 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-003-0043-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-003-0043-0