ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Depression is common among individuals with osteoarthritis and leads to increased healthcare burden. The objective of this study was to examine excess total healthcare expenditures associated with depression among individuals with osteoarthritis in the US.

DESIGN

Adults with self-reported osteoarthritis (n = 1881) were identified using data from the 2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Among those with osteoarthritis, chi-square tests and ordinary least square regressions (OLS) were used to examine differences in healthcare expenditures between those with and without depression. Post-regression linear decomposition technique was used to estimate the relative contribution of different constructs of the Anderson’s behavioral model, i.e., predisposing, enabling, need, personal healthcare practices, and external environment factors, to the excess expenditures associated with depression among individuals with osteoarthritis. All analysis accounted for the complex survey design of MEPS.

KEY RESULTS

Depression coexisted among 20.6 % of adults with osteoarthritis. The average total healthcare expenditures were $13,684 among adults with depression compared to $9284 among those without depression. Multivariable OLS regression revealed that adults with depression had 38.8 % higher healthcare expenditures (p < 0.001) compared to those without depression. Post-regression linear decomposition analysis indicated that 50 % of differences in expenditures among adults with and without depression can be explained by differences in need factors.

CONCLUSIONS

Among individuals with coexisting osteoarthritis and depression, excess healthcare expenditures associated with depression were mainly due to comorbid anxiety, chronic conditions and poor health status. These expenditures may potentially be reduced by providing timely intervention for need factors or by providing care under a collaborative care model.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Arthritis is a chronic rheumatic condition and contributes to high rates of disability and healthcare expenditures.1–3 Approximately 22 % of the US adult population has been reported to have some type of arthritis.4Osteoarthritis is the most common type of arthritis. With increasing obesity, physical inactivity and an aging population, the prevalence of osteoarthritis and its consequent economic burden is likely to increase in the US.5

Depression and depressive symptoms are common among individuals with osteoarthritis,6–8 as osteoarthritis causes chronic pain and disability, which are both underlying factors for depression.7 The prevalence of depression among individuals with arthritis can be very high, ranging from 17 to 27 %, depending on the type of arthritis and definition of depression.9–12 It has been estimated that among adults in the age group of 54–65 years, 18.1 % of major depression is attributable to arthritis.10 A greater proportion of individuals with osteoarthritis are reported to have depression (12.4 %) as compared to individuals without osteoarthritis.8

Although several studies have examined the excess healthcare expenditures associated with depression in other chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and asthma,13–15 no previous US study has estimated excess healthcare expenditures associated with depression among individuals with osteoarthritis or factors that contribute to these excess expenditures.

Such excess expenditures due to depression can be due to presence of multimorbidity among individuals with osteoarthritis. Individuals with osteoarthritis often report comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, depression, respiratory disease and obesity. It is also evident from the previous literature that individuals with osteoarthritis have at least two comorbid conditions and three-fourths of the individuals with osteoarthritis have three or more comorbid conditions.16 The presence of Multimorbidity and depression among individuals with osteoarthritis can lead to increased pain and functional disability,17which in turn may contribute to excess healthcare expenditures among adults with osteoarthritis and depression compared to those with osteoarthritis and no depression.

It is important to examine excess healthcare expenditures associated with depression, because many new policy initiatives have focused on care management of high-cost, high-need patients to improve quality and reduce future costs. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) has also created incentives for providers through shared savings programs within accountable care organizations to provide collaborative care with reduced cost. Policy makers are also experimenting with various reimbursement initiatives, such as bundled payments for episodes of care to reduce costs. All these financial reforms require the identification of high-cost, high-need patients. An understanding of factors that contribute to high healthcare expenditures among those with complex healthcare needs, such as those with co-occurring osteoarthritis and depression, may help providers in developing and implementing appropriate care management with reduced costs.

Therefore, the primary objective of the current study is to estimate excess total healthcare expenditures associated with depression among a nationally representative sample of US adults with osteoarthritis, and examine the extent to which individual-level factors contribute to the excess total healthcare expenditures associated with depression by using a post-regression linear decomposition approach.

METHODS

Analytical Framework

The Andersen’s behavioral model for healthcare services utilization was adopted to provide a conceptual framework to the study.18 This model has been used extensively to examine the relationship between predisposing, enabling, need, personal health practices, and external environment factors, and healthcare services utilization and expenditures. The model posits that healthcare service utilization (in this study, it is in the form of total healthcare expenditures) can be predicted through individual level factors: 1) predisposing—gender, race, and age; 2) enabling—marital status, education, employment, poverty status, insurance coverage, and usual source of care; 3) need—perceived physical and mental health status, anxiety, presence of cardiovascular conditions, and other chronic conditions; 4) personal health practices—body-mass index (BMI), exercise, and smoking status; and 5) external environment—metro versus non-metro residence.

Design

We used a retrospective cross-sectional design.

Data Source

We used data from the 2010 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), a large-scale nationally representative survey of US households, families and non-institutionalized individuals. Using a panel design, the survey collects information on healthcare utilization, expenditures associated with these services, and the sources of payment.19 The survey also elicits information on medical and mental health conditions.20,21 This information is collected verbatim and converted into International Classification of Disease, Ninth edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes by professional coders. These ICD-9-CM codes were further converted in clinical classification codes, and for the purpose of this study, either or both of them were used.22

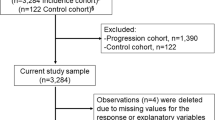

Analytical Sample

The analytical sample consisted of adults with osteoarthritis (n = 1881). Individuals with osteoarthritis were identified using clinical classification code “203.” These individuals were 22 years or older, alive during the calendar year, and reported having positive healthcare expenditures. Individuals with osteoarthritis and depression were identified using both full-year consolidated data files and medical condition files.

Measures

Dependent Variable: Total Healthcare Expenditures

Total healthcare expenditures consisted of payments made for hospital inpatient stays, emergency room visits, outpatient visits, office-based medical provider visits, prescription drugs, dental visits, home health visits and other medical expenses.22 Other medical expenses included ambulatory care, vision and dental care, durable medical equipment, and other items such as hearing devices, medical equipment, etc., that are purchased or rented. MEPS captured payments for these services from the following sources: Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE (a health care program offered by the Military Health System for active duty service members, National Guard and Reserve members, their families, survivors, and certain former spouses), Veterans Affairs including CHAMPVA (Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs), and other federal, state and local sources, out-of-pocket expenses, private insurance, worker’s compensation and other unclassified resources.

Key Independent Variable: Presence of Depression

The presence of depression was identified from medical condition file using the clinical classification code “657” or ICD-9-CM code “296” or “311,” which represents both bipolar and depressive disorders.

Other Independent Variables

Other independent variables were: predisposing, enabling, need, personal health practices, and external environment factors, as suggested by Anderson behavioral model. Predisposing factors were gender (female, male), race (white, African Americans, Latino, and others), and age (22–39, 40–49, 50–64, and 65 years and older). Enabling factors included marital status (married, widow, separated/divorced and never married), education (less than high school, high school and more than high school), employment (employed, not employed), poverty (poor, near poor, middle income and high income), insurance coverage (private, public and uninsured), and usual source of care. The poverty status variable was defined using the federal poverty level (FPL), which uses family size and composition. Poor was defined as incomes less than the FPL, near poor as 100 % to less than 200 % of the FPL, middle income as 200 % to less than 400 % of the FPL, and high income as 400 % of the FPL or greater. Need factors included perceived physical and mental health status (excellent/very good, good, and fair/poor), anxiety (anxiety and no anxiety), chronic conditions (presence of zero, one, two, the or more chronic conditions) such as anemia, asthma, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cancer, and thyroid disorder, and presence of cardiovascular conditions (yes, no) such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease. Personal health practices included BMI (under/normal weight, overweight, and obese), physical activity (three times per week, and no exercise), and smoking status (current smoker and others). External environment included metro status (metro and no metro).

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests were used to examine unadjusted subgroup differences in the characteristics of those with depression and osteoarthritis as compared to those without depression. Ordinary least square regression (OLS) on log-transformed expenditures was used to evaluate the magnitude of the association between depression and healthcare expenditures. In this regression, predisposing, enabling, need, personal healthcare practices, and external environment factors were included as other independent variables.

To better understand the contribution of each patient level factor to the differences in expenditures among adults with and without depression, a post-regression linear decomposition was performed. This technique, known as “linear decomposition,” was developed by Blinder-Oaxaca.23,24 The decomposition technique enables investigators to assess how much of the differences in expenditures of the two groups (depression and no depression) may be due to: 1) observable and measured factors, such as predisposing, enabling, need, personal health practices, and external environment factors; 2) unobservable (such as genetic disposition for severe depression) and other unmeasured factors in this study; and 3) an interaction that accounts for the differences in the characteristics and regression coefficients that may exist simultaneously.25 The interaction term can be included either in the explained portion or in the unexplained portion. The choice is left to the analysts based on interpretation rather than statistics. We included the interaction term in the unexplained portion, because part of the difference is also due to differences in regression coefficients.

The decomposition approach categorizes healthcare expenditures into an “explained portion” and an “unexplained portion.” The explained portion is calculated by multiplying the differences in characteristics by estimated regression coefficients of these characteristics. Regression coefficients, also referred to as regression weights, could be based on regression coefficients derived from OLS regression among adults with depression or regression coefficients derived from OLS regression among adults without depression. To counter this problem, regression estimates from OLS regression among adults with and without depression can be used. In this paper, Neumark’s approach is used.26 In this approach, regression coefficients are derived by pooling observations from the two groups without controlling for depression. All analyses accounted for the complex survey design of MEPS, and were conducted using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.3, Cary, NC, USA. Surveymeans, surveyfreq, and surveyreg procedures were used in SAS to account for clustering, stratification, and weights.

RESULTS

Among adults with osteoarthritis, approximately 21 % had coexisting depression. The characteristics of the sample differed by depression status. As compared to individuals without depression, those with depression had a higher proportion of females (62.9 % vs. 75.8 %), individuals between 50 and 64 years of age (36.8 % vs. 50.0 %), and those who were poor (10.2 % vs. 15.7 %), obese (36.7 % vs. 47.0 %), and current smokers (11.1 % vs. 23.5 %).A higher proportion of individuals with depression reported fair/poor perceived physical health (42.8 % vs. 20.9 %), fair/poor perceived mental health (32.7 % vs. 8.6 %), anxiety (26.7 % vs. 9.4 %), and two or more chronic conditions (31.6 % vs. 23.2 %), as compared to individuals without depression. Chi-square tests revealed significant subgroup differences in the characteristics of the two groups for all domains of the Andersen’s model (Table 1).

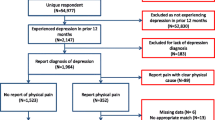

Figure 1 presents the average total healthcare expenditures among individuals with and without depression. Among individuals with osteoarthritis, the average total healthcare expenditures were approximately $13,684 for those with depression, compared to $9,285 for those without depression.

Table 2 presents results from separate OLS regressions on log-transformed total healthcare expenditures for those with and without depression. The regression coefficient of depression (or any categorical variable) can be interpreted by exponentiating the regression coefficients of a dummy variable and subtracting one (i.e., percent change = eβ – 1). After adjusting for predisposing, enabling, need, personal health practices, and external environment factors, adults with depression had 38.8 % (β = 0.328, p < 0.001) greater healthcare expenditures compared to those without depression.

Separate OLS regressions among those with and without depression revealed that the association between expenditures and subject characteristics was not similar. For example, the uninsured had lower healthcare expenditures compared to those with private insurance among adults with depression. However, the relationship was reversed among adults without depression (Table 2). Adults without health insurance had greater healthcare expenditures compared to those with private insurance. Similarly, among individuals without depression, those reporting good perceived physical health status had 35.5 % higher healthcare expenditures compared to those with excellent/very good health (β = 0.304, p < 0.001). Such significance was not observed for individuals with depression reporting good perceived physical health status. In contrast, other factors, i.e., fair/poor perceived physical health, other chronic conditions and CVD, had similar associations with expenditures. For example, among those with depression, individuals reporting fair/poor perceived physical health had 138 % (β = 0.868, p < 0.001) higher healthcare expenditures compared to those with excellent/very good health. Similarly, among those without depression, individuals reporting fair/poor perceived physical health had 83 % (β = 0.604, p < 0.001) higher healthcare expenditures compared to those with excellent/very good health.

Table 3 summarizes the results from the post-regression linear decomposition approach. The predicted log-transformed expenditures were 8.83 for adults with depression and 8.25 for adults without depression, suggesting a difference of 0.548. Of this difference, 53.84 % was explained by the differences in the characteristics of the two groups. This difference varied from 53.84 % when parameter estimates from OLS regression among individuals with depression were used as weights, to 36.87 % when parameter estimates from OLS regression among individuals without depression were used as weights. When parameter estimates from pooled OLS regression were used as weights, 52.6 % of the difference in average total healthcare expenditures was explained by all the individual level factors included in the study. In our analysis, 16.98 % of the differences were due to the interaction term.

Among patient level variables, need factors contributed the most to the total explained difference. This difference varied from 52.87 % when parameter estimates from OLS regression among individuals with depression were used as weights, to 50.91 % when parameter estimates from OLS regression among individuals without depression were used as weights. When parameter estimates from pooled OLS regression were used as weights, 58.88 % of the difference in average total healthcare expenditures was explained by need factors included in the study.

Explained portions of predisposing, enabling, personal health practices and external environment had negative signs. These negative signs suggest that, keeping other factors constant, if the “depression” group had the same distribution of characteristics as the “no depression” group (predisposing, enabling, personal health practices, and external environment factors), the total healthcare expenditures of individuals with depression would be higher.

DISCUSSION

We estimated excess total healthcare expenditures associated with depression among adults with osteoarthritis, and elicited patient level factors contributing to excess total healthcare expenditures. We found that among individuals with osteoarthritis, those with depression had approximately 38.8 % greater total healthcare expenditures compared to those without depression, even after adjusting for predisposing, enabling, need, personal healthcare practices, and external environment factors.

It is plausible that individuals with co-occurring chronic physical conditions and depression (i.e., osteoarthritis and depression) may have more medical care utilization than individuals with only physical conditions (i.e., osteoarthritis). It has been documented in a study on veterans with diabetes that those with mental health conditions such as depression may incur higher direct general medical care costs than costs for mental healthcare.27 Among Medicare beneficiaries with common chronic conditions, co-occurring depression more than doubled the odds of hospital admissions for medical care.28

The results from post-regression linear decomposition indicate that the explained portion varied from 53.84 % when regression coefficients from the osteoarthritis and depression group were used, to 36.87 % when regression coefficients from the osteoarthritis group were used. Using the pooled regression weights, 58.88 % of the difference in total expenditures was explained by the need factors. In our study sample, adults with depression were more likely to report fair/poor physical health compared to those without depression. It is possible that adults with depression may perceive their physical health to be fair/poor due to depressive symptoms and functional limitations due to depression. Individuals with fair or poor perceived health status may need greater medical care leading to greater healthcare expenditures, compared to individuals with excellent perceived physical healthcare status.

Thus, the explained portion quantified how much of total healthcare expenditures would be reduced if adults with osteoarthritis and depression had need factors similar to those of adults with osteoarthritis and no depression.

However, when we weighted the differences in characteristics by the regression coefficients from the osteoarthritis group, we found that 50.91 % of the expenditure gap was explained by need factors such as perceived physical and mental health, anxiety, presence of cardiovascular, and other chronic conditions. Thus, the extent to which the excess expenditures could be reduced would depend not only on equalizing the need factors between the two groups, but also on the relationships between need factors and healthcare expenditures.

An important point to note here is the presence of multimorbidity in those with depression. In our study sample, adults with depression had higher rates of co-existing CVD and other chronic conditions compared to those without depression. Therefore, it is not surprising that higher prevalence of multimorbidity in the “depression” group can lead to higher medical care utilization and expenditures compared to the “no depression group.” These findings have implications for healthcare delivery reforms that focus on care management, along with reimbursement strategies to reduce costs. For example, the model known as DIAMOND (Depression Improvement Across Minnesota Offering a New Direction) included both an integrated care component and bundled payments to primary care providers for depression. This model has been found to be effective in reducing depression remissions, and is based on the IMPACT (Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment) intervention that uses a collaborative approach for providing treatment.29,30 It is also evident from the results of a systematic review of 45 studies that receiving collaborative care as compared to usual care has been found to be beneficial among those with major depressive disorder for improving the treatment outcomes such as adherence and functional status, and for reducing the financial burden.31 It has to be noted that the demonstration projects for providing coordinated care for high-cost and high-need patients have also proven to be cost-effective. Specifically, the Massachusetts General Physicians Organization (MGH), which targeted patients with multiple chronic conditions and high cost, has been shown to reduce costs and improve care.32

Findings in this study can be interpreted after considering its strengths and limitations. The main strengths of our study are the use of a large nationally representative data set, a comprehensive list of independent variables that may affect expenditures, and availability of healthcare expenditures from all sources. We contributed to the knowledge base on this topic by examining the extent to which individual level factors contributed to the excess expenditures among individuals with arthritis using a post-regression linear decomposition technique. However, certain limitations associated with our study should be noted. All measures were self-reported and may be subject to recall bias. Nearly 50 % of excess healthcare expenditures associated with depression remained unexplained. We could not adjust for other factors, such as severity of osteoarthritis and depression. Inclusion of these factors could have increased the explained portion of excess expenditures associated with depression. Additionally, the decomposition technique may provide quantitative results by distinguishing between the explained and unexplained portions of the differences in healthcare expenditures; it does not address the underlying mechanisms, nor does it identify the reasons for differences in average characteristics between the two groups.

CONCLUSION

This is the first study to use nationally representative data to estimate healthcare expenditures associated with depression among individuals with osteoarthritis. We found that depression is associated with 38.8 % higher expenditures in individuals with osteoarthritis. By using a linear-decomposition approach, we also identified that higher prevalence of need factors, such as poor perceived health status, anxiety, other chronic conditions and CVD, explained 52 % of the excess expenditures. Our findings suggest that routine screening and a collaborative care approach may be needed to prevent clinical depression and reduce the depression-associated costs.

REFERENCES

Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35.

Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15–25.

Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Joski P. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Aff. 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:W4-437-445.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of self-reported arthritis or chronic joint symptoms among adults–United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(42):948–950.

Yelin E, Cisternas M, Foreman A, Pasta D, Murphy L, Helmick CG. National and state medical expenditures and lost earnings attributable to arthritis and other rheumatic conditions—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(1):4.

Sale JE, Gignac M, Hawker G. The relationship between disease symptoms, life events, coping and treatment, and depression among older adults with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(2):335–342.

Rosemann T, Backenstrass M, Joest K, Rosemann A, Szecsenyi J, Laux G. Predictors of depression in a sample of 1,021 primary care patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(3):415–422.

Gore M, Tai KS, Sadosky A, Leslie D, Stacey BR. Clinical comorbidities, treatment patterns, and direct medical costs of patients with osteoarthritis in usual care: a retrospective claims database analysis. J Med Econ. 2011;14(4):497–507.

Creed F. Psychological disorders in rheumatoid arthritis: a growing consensus? Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49(10):808.

Dunlop DD, Lyons JS, Manheim LM, Song J, Chang RW. Arthritis and heart disease as risk factors for major depression: the role of functional limitation. Med Care. 2004;42(6):502–511.

Bruce TO. Comorbid depression in rheumatoid arthritis: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10(3):258–264.

Godha D, Shi L, Mavronicolas H. Association between tendency towards depression and severity of rheumatoid arthritis from a national representative sample: the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(7):1685–1690.

Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):464.

Welch CA, Czerwinski D, Ghimire B, Bertsimas D. Depression and costs of health care. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(4):392–401.

Nichols GA, Bell TJ, Pedula KL, O’Keeffe-Rosetti M. Medical care costs among patients with established cardiovascular disease. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(3):e86–e93.

Kadam UT, Croft PR. Clinical comorbidity in osteoarthritis: associations with physical function in older patients in family practice. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(9):1899–1904.

Wilkie R, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Jordan KP, Lacey R, McBeth J. Reasons why multimorbidity increases the risk of participation restriction in older adults with lower extremity osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study in primary care. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(6):910–919.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

AHRQ. MEPS-HC Sample Design and Collection Process. http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/hc_data_collection.jsp. Accessed March 27th, 2015.

AHRQ. MEPS HC-120 2008 Medical Conditions File. 2010; http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h120/h120doc.pdf. Accessed March 27th, 2015.

Machlin S, Cohen J, Elixhauser A, Beauregard K, Steiner C. Sensitivity of household reported medical conditions in the medical expenditure panel survey. Med Care. 2009;47(6):618–625.

AHRQ. MEPS HC-138: 2010 Full Year Consolidated Data File. 2010; http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h121/h121doc.shtml. Accessed March 27th, 2015.

Oaxaca R. Male–female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int Econ Rev. 1973;14(3):693–709.

Blinder AS. Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. J Hum Resour. 1973;8(4):436–455.

Jann B, Zürich E. The Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. Stata J. 2008;8(4):453–479.

Neumark D. Employers’ discriminatory behavior and the estimation of wage discrimination. J Hum Resour. 1988;23(3):279–295.

Banerjea R, Sambamoorthi U, Smelson D, Pogach LM. Expenditures in mental illness and substance use disorders among veteran clinic users with diabetes. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2008;35(3):290–303.

Himelhoch S, Weller WE, Wu AW, Anderson GF, Cooper LA. Chronic medical illness, depression, and use of acute medical services among Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2004;42(6):512–521.

A new direction in depression treatment in Minnesota: DIAMOND program, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Bloomington, Minnesota. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(10):1042–44. http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/ps.2010.61.10.1042.

Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(18):2428–2429.

Katon W, Guico-Pabia CJ. Improving quality of depression care using organized systems of care: a review of the literature. Prima Care companion to CNS disorders. 2011;13(1):e1–e8.

Urato C, David BNM, Jerry C. Evaluation of Medicare Care Management for High Cost Beneficiaries (CMHCB) Demonstration: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts General Physicians Organization (MGH). Baltimore: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2010.

Acknowledgements

The project described was partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U54GM104942. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or policy or the position of West Virginia University (WVU) or any other affiliated organizations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agarwal, P., Sambamoorthi, U. Healthcare Expenditures Associated with Depression Among Individuals with Osteoarthritis: Post-Regression Linear Decomposition Approach. J GEN INTERN MED 30, 1803–1811 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3393-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3393-4