Abstract

Does the “shaming” of human rights violations influence foreign aid delivery decisions across OECD donor countries? We examine the effect of shaming, defined as targeted negative attention by human rights international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), on donor decisions about how to deliver bilateral aid. We argue that INGO shaming of recipient countries leads donor governments, on average, to “bypass” the recipient government in favor of non-state aid delivery channels, including international and local NGOs and international organizations (IOs). However, we expect this relationship to be conditional on a donor country’s position in the international system. Minor power countries have limited influence in global affairs and are therefore more able to centrally promote human rights in their foreign policy. Major power countries, on the other hand, shape world politics and often confront “realpolitik” concerns that may require government-to-government aid relations in the presence of INGO shaming. We thus expect aid officials of minor donor countries to be more likely to condition aid delivery decisions on human rights shaming than their counterparts of major donor countries. Using compositional data analysis, we test our argument using originally collected data on human rights shaming events and an originally constructed measure of bilateral aid delivery in a time-series cross-sectional framework from 2004 to 2010. We find support for our hypotheses: On average, OECD donor governments increase the proportion of bypass when INGOs shame the recipient government. When differentiating between donor types we find that this finding holds for minor but not for major powers. These results add to both our understanding of the influences of aid allocation decision-making and our understanding of the role of INGOs on foreign-policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Cingranelli and Pasquarello (1985) show that the U.S. cuts economic but not military aid support to countries with human rights violations. Lebovic and Voeten (2009) find that donor governments pressure international organizations to sanction repressive behavior with cuts in multilateral aid, while bilateral aid flows between donors and the repressive recipient government remain unchanged. Nielsen (2013) disaggregates bilateral aid into its various sectors, showing that human rights violations lead donor governments to cut economic aid but not humanitarian aid. The latter two findings by Lebovic and Voeten (2009) and Nielsen (2013) make important contributions to the literature as they disaggregate aid and are based on a more nuanced understanding of the decision-making process. Both works theorize and test for important heterogeneity within foreign aid.

Multilateral organizations like the UN increasingly rely on bilateral aid as source of financing, which increases the amount of projects that they implement directly on behalf of donor governments (Katherine 2015; Eichenauer and Knack 2014). Although multilaterals engage with recipient authorities in project implementation they often impose strict conditions. As Lebovic and Voeten (2009) find, international organizations promote human rights more forcefully than bilateral donor governments.

Others bilateral aid tactics include the imposition of conditionality, or the appropriation of aid budgets into aid sector.

Please see Murdie and Peksen (2014, 218) for a discussion of these World Values Survey findings.

Author Interview with Senior Government Official, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Stockholm, June 18, 2013.

It is important to note that we do not expect that the entire foreign aid budget earmarked for the public sector in any given year will be shifted towards non-state actors. Many collaborative donor-recipient projects have a multi-year time frame and are implemented with the involvement of donor agencies. While many of these projects may be more difficult to reorient in terms of delivery method, more programmatic and budget-oriented funding can more easily be redirected to alternative delivery agents. However, according to extensive author interviews with more than 70 aid decision-makers across OECD donor countries, aid officials have the power to freeze or withhold significant funding even for multi-year projects if deemed necessary, which may be in the face of unexpected anti-democratic behavior or corruption.

Evidence of this trend documented in country reports by Human Rights Watch (www.hrw.org/publications/reports) and Amnesty International (https://www.amnesty.org/en/countries/africa/ethiopia/).

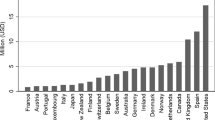

As donor governments have increased their capacity for reporting over time, the coverage of the delivery channel data has steadily increased. In 2004 and 2005 Austria, Belgium, Sweden, and the United States reported data on this dimension. In 2006, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, and Portugal joined the group of reporting OECD donors. By 2007 all OECD provided data on delivery channels with the exception of Luxembourg and Spain. Across all these countries data coverage is steadily increasing across recipient countries, without any evidence of systematic underreporting on particular recipient countries.

However, as Dietrich (2016) shows, donor political economies influence the degree to which they respond to low governance quality in recipient countries with bypass tactics.

The results are robust to alternative cluster specifications on the recipient country and the donor country.

For example, we should expect differential effects for distance. Minor power donor governments have less reach and less capacity to implement their own projects. As distance increases we should expect minor powers to decrease bypass and channel more aid through the government-to-government channel. For major powers we might not expect there to be as strong as an effect, perhaps we even expect the opposite outcome.

Again, the results are robust to alternative cluster specifications.

The Appendix is available on the Review of International Organization’s webpage.

Given our short time span and small within-unit sample sizes we opt for the inclusion of donor and recipient fixed effects instead of dyad fixed effects. If the within unit sample size is small, the unit effects alone may account for most of the variation in our bypass variable. What is more there are time-invariant dyadic variables in the specification that are very important to include in the model, including distance. If we included dyadic fixed effects this control would drop out as it is perfectly collinear with the set of unit dummy variables. This makes it impossible to estimate the unique effects of that variable. We nonetheless estimated the model using dyad fixed effects and the shaming coefficient (with a p-value of 0.108) just misses conventional levels of statistical significance.

We present the results in the Appendix Table 1, Models 1 through 4.

We thank the editor and one anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

The sample is slightly bigger as it excludes the Total Aid Per Capita measure. This measure captures per capita levels of foreign aid that flow between donor and recipient pair given that at least 90 percent of the channel of delivery data was reported to the OECD CRS.

Table 2 in the Appendix presents further tests that explore the effects of INGO Shaming on levels of social and economic sector aid. Again, INGO Shaming is not systematically associated with levels of aid.

Table 3 in the Appendix presents the results for the INGO coefficients from three different samples that exclude the top 10, top 15, and top 20 most fragile states in the international system. The model specifications include ones with and ones without the lagged dependent variable. The size of the coefficients are increasing in size as the estimation sample becomes more limited to include only aid-receiving countries with functionally competent governments.

We thank one anonymous reviewer for raising this issue and suggesting the alternative proxy.

We re-estimate the model using a seemingly-unrelated regression framework. The results are very similar to the independent subsample analysis.

We thank one anonymous reviewer suggestion and present the findings in Table 8 in the Appendix.

Since we should expect major and minor powers to respond differently to at least some confounders we include the controls in interaction with Minor Donor.

References

Acht, M., Mahmoud, T., & Thiele, R. (2015). Corrupt governments do not receive more state-to-state aid: governance and the delivery of foreign aid through non-state actors. Journal of Development Economics, 114, 20–33.

AFD (2011). Les Francais e l’aide au developpement. Agence Francaise de Developpement.

Aitchison. (1986). The statistical analysis of compositional data. London: Chapman Hall.

Alesina, A., & Dollar, D. (1992). Human rights and economic aid allocation under Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter. African Studies Review, 36(1), 147–167.

Alesina, A., & Dollar, D. (2000). Who gives foreign Aid to Whom and Why? African Studies Review, 5, 33–63.

Apodaca, C., & Stohl, M. (1999). United states rights policy and foreign assistance. International Studies Quarterly, 43(1), 185–198.

Ausderan, J. (2014). How naming and shaming affects human rights perceptions in the shamed country. Journal of Peace Research, 51(1), 81–95.

Baehr, P., & Castermans-Holleman, M. (1994). The role of human rights in foreign policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Baehr, P.R, Castermans-Holleman, M.C, & Grünfeld, F. (2002). Human rights in the foreign policy of the Netherlands1. Human Rights Quarterly, 24, 992–1010.

Bandstein, S. (2007). What determines the choice of aid modalities? A framework for assessing incentive structures. SADEV Report 4.

Bapat, N. (2011). Terrorism, democratization, and U.S. foreign policy. Public Choice, 149(3-4), 315–335.

Barry, C., Chad, C., & Flynn, M. (2013). Avoiding the spotlight: human rights shaming and foreign direct investment. International Studies Quarterly, 57(3), 532–544.

Barry, C., Sam, B., Clay, C., Flynn, M., & Murdie, A. (2015). Choosing the Best House in a Bad Neighborhood: Location Strategies of Human Rights INGOs in the Non-Western World. International Studies Quarterly, 59(1), 86–98.

Bennett, S., & Stam, A. (2000). EUGene: a conceptual manual. International Interactions, 26, 179–204.

Berger, L. (2012). Guns, butter, and human rights the congressional politics of US aid to Egypt. American Politics Research, 40(4), 603–635.

Bond, D, Joe, B, Churl, O, Jenkins, JC, & Taylor, CL (2003). Integrated data for events analysis (IDEA): an event typology for automated events data development. Journal of Peace Research, 40(6), 733–745.

Bryant, KV (2015). Funding aid agencies: the political determinants of core v. non-core. Unpublished Manuscript.

Brysk, A (1993). From above and below social movements, the international system, and human rights in Argentina. Comparative Political Studies, 26(3), 259–285.

Brysk, A. (2009). Global good Samaritans: human rights as foreign policy. Oxford University Press.

Bueno de Mesquita, B, & Smith, A (2009). A political economy of foreign aid. International Organization, 63, 309–340.

Carleton, D, & Stohl, M (1985). The foreign policy of human rights: rhetoric and reality from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan. Human Rights Quarterly, 7(2), 205–229.

CIDA (2004). Canadian attitudes toward development assistance. Prepared for the Canadian International Development Agency.

Cingranelli, D., & Richards, D. (2010). The Cingranelli and Richards human rights data project. Human Rights Quarterly, 32, 395–418.

Cingranelli, DL, & Pasquarello, TE (1985). Human rights practices and the distribution of us foreign aid to Latin American countries. American Journal Political Science, 29, 539–563.

David, D., Murdie, A., & Steinmetz, C.G. (2012). Makers and shapers: human rights INGOs and public opinion. Human Rights Quarterly, 34(1), 199–224.

Dietrich, S. (2013). Bypass or engage? Explaining donor delivery tactics in foreign aid allocation. International Studies Quarterly, 57(4), 698–712.

Dietrich, S (2016). Donor political economies and the pursuit of aid effectiveness. International Organization, 70(1), 65–102.

Dietrich, S., & Wright, J. (2015). Foreign aid allocation tactics and democratic change in Africa. Journal of Politics, 77(1), 216–234.

Dreher, A. (2006). Does globalization affect growth? Evidence from a new index of globalization. Applied Economics, 38(10), 1091–1110.

Dreher, A., Moelders, F., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2010). Aid delivery through non-governmental organizations: does the aid channel matter for the targeting of Swedish aid? World Economy, 33(2), 147–176.

Dreher, A., Nunnenkamp, P., Oehler, J., & Weisser, J. (2012a). Acting autonomously or mimicking the state and peers? A panel tobit analysis of financial dependence and aid allocation by Swiss NGOs. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 60(4), 829–867.

Dreher, A., Nunnenkamp, P., Thiel, S., & Thiele, R. (2012b). Aid allocation by German NGOs: does the degree of public refinancing matter? World Economy, 35 (11), 1448–1472.

Eichenauer, V., & Knack, S. (2014). Bilateralizing multilateral aid? Aid allocation by world bank trust funds. Unpublished Manuscript.

Escribà-Folch, A. (2010). Repression, political threats, and survival under autocracy. Available at SSRN 1705508.

Felbermayr, G., & Groeschl, J. (2013). Naturally negative: the growth effects of natural disasters. Journal of Development Economics, 111, 92–106.

Franklin, J.C. (2008). Shame on you: the impact of human rights criticism on political repression in Latin America. International Studies Quarterly, 52(1), 187–211.

Freedom House (2012). www.freedomhouse.org.

Gleditsch, N.P., Peter Eriksson, W., Sollenberg, M., & Strand, H. (2002). Armed conflict 1946-2001: a new dataset. Journal of Peace Research, 39(5), 615–637.

Hendrix, C.S., & Wong, W.H. (2013). When is the pen truly mighty? Regime type and the efficacy of naming and shaming in curbing human rights abuses. British Journal of Political Science, 43, 651–672.

Kaufman, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2012). Governance Matters VI http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.asp [Accessed: 12 September 2012].

Keck, M.E., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond borders: advocacy networks in international politics. Cambridge University Press.

Kuziemko, I., & Werker, E. (2009). How much is a seat on the security council worth? Foreign aid and bribery at the United Nations. Journal of Political Economy, 114(5), 905–930.

Lebovic, J.H., & Voeten, E. (2009). The cost of shame: international organizations and foreign aid in the punishing of human rights violators. Journal of Peace Research, 46, 79–97.

Licht, A.A. (2010). Coming into money: the impact of foreign aid on leader survival. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54(1), 58–87.

Morgenthau, H. (1979). Human rights & foreign policy. First Distinguished CRIA Lecture on Morality and Foreign Policy.

Murdie, A., & Peksen, D. (2013). The impact of human rights INGO activities on economic sanctions. The Review of International Organizations, 8(1), 33–53.

Murdie, A., & Peksen, D. (2014). The impact of human rights INGO shaming on humanitarian interventions. Journal of Politics, 76(1), 215–228.

Murdie, A., & Urpelainen, J. (2015). Why pick on us? Environmental INGOs and state shaming as a strategic substitute. Political Studies, 63(2), 353–372.

Murdie, A.M., & Davis, D.R. (2012b). Shaming and blaming: using events data to assess the impact of human rights INGOs1. International Studies Quarterly, 56 (1), 1–16.

Neumayer, E. (2003a). Do human rights matter in bilateral aid allocation? A quantitative analysis of 21 donor countries. Social Science Quarterly, 84(3), 650–666.

Neumayer, E. (2003b). Is respect for human rights rewarded? An analysis of total bilateral and multilateral aid flows. Human Rights Quarterly, 25(2), 510–527.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 1417–1426.

Nielsen, R. (2013). Rewarding human rights? Selective aid sanctions against repressive states. International Studies Quarterly, 52(9), 1–13.

Page, B., Shapiro, R., & Dempsey, G. (1987). What moves public opinion? American Political Science Review, 81, 23–44.

Perkins, R., & Neumayer, E. (2010). The organized hypocrisy of ethical foreign policy: human rights, democracy and Western arms sales. Geoforum, 41(2), 247–256.

Rioux, J.-S., & Van Belle, D.A. (2005). The influence of le monde coverage on french foreign aid allocations. International Studies Quarterly, 49, 481–502.

Risse, T., Ropp, S., & Sikkink, K. (1999). The power of human rights: international norms and domestic change. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ritter, E.H. (2014). Policy disputes, political survival, and the onset and severity of state repression. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 58(1), 143–168.

Ron, J., Ramos, H., & Rodgers, K. (2005). Transnational information politics: NGO human rights reporting, 1986–2000. International Studies Quarterly, 49(3), 557–588.

Vreeland, J., & Dreher, A. (2014). The political economy of the united nations security council. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tim Buethe, Stephen Chaudoin, Desha Girod, Raymond Hicks, Stephen Knack, Matthew Winters, Joseph Wright, participants at the 2014 conference on The Political Economy for International Organizations and the 2014 conference of the American Political Science Association, as well as two anonymous reviewers and Axel Dreher for valuable comments and suggestions. All errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dietrich, S., Murdie, A. Human rights shaming through INGOs and foreign aid delivery. Rev Int Organ 12, 95–120 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-015-9242-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-015-9242-8

Keywords

- Foreign aid

- Human rights

- Foreign policy

- International non-governmental organizations

- International organizations