Abstract

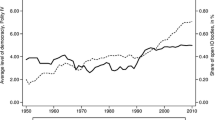

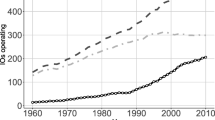

This article uses the informal governance framework to elucidate the connection between regime transition and participation in regional international organizations (IOs). In particular, this study focuses on non-democratic regional IOs and examines the empirical case of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). We investigate how the level of regime transition of each CIS member state affects its participation in the CIS. The paper utilizes an original dataset that contains information regarding the number of CIS-related agreements that have been signed by each CIS member state during the 1991–2010 time period, which can be used to measure the level of participation of each state in the CIS. We find that states with a lower level of democratization and a higher level of marketization are more likely to participate in agreements within the CIS. The paper contributes to the wider application of informal governance framework by demonstrating the usefulness of these theories for understanding the nature and dynamics of regional IOs, such as the CIS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Examples of this type of IO include the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, ASEAN (during the early years of its existence) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

For example, there is much debate regarding whether EU decision-making processes are democratic. However, by the standards of the definition that is provided above, it is a democratic IO.

Compared with democracies, non-democracies are generally more likely to use informal governance mechanisms in their internal political procedures (Gel’man 2012); furthermore, in non-democracies, domestic political processes are typically less tolerant of any types of restrictions to the power of the incumbent. Therefore, decisions that appear to restrict a leader’s power should be more frequently overruled by a non-democratic leader than by a democratic leader.

We use “marketization” and “economic reforms” interchangeably to refer to the extent to which market economy institutions are established and functional.

This statement does not imply that there are no other benefits of IO membership and participation during “ordinary times.” However, these benefits are equally relevant for countries with different political regimes and therefore cannot yield predictions regarding whether democratization should be correlated with levels of IO participation.

Note that although a number of papers have identified a mutually reinforcing relationship between democratization and regional cooperation, in a study of a regional IO consisting of nations that have not experienced high levels of democratization (Mercosur), Remmer (1998) finds much less evidence of the existence of this relationship.

An obvious question in this context is why Russia provides these benefits to CIS countries. One reason could be internal political gains, given that the Russian population is strongly in favor of post-Soviet integration (Rose and Munro 2008). Another benefit is ensuring that the “dormant” institutional framework of the CIS functions and can be re-activated at any point in the future.

Prior to the revolutionary wave, the CIS regularly dispatched its observers to elections in the post-Soviet countries; however, in the second half of the 2000s these practices have been institutionalized (Status of the Mission of Observers in 2004, International Institute of Monitoring of Development of Democracy, Parliamentarianism and Protection of Human Rights in 2006) and expanded.

One possible case of this type of enforcement is Russia’s support of Abkhazia during its secession war against Georgia in 1992–93. This support could be interpreted as an instance in which Russia used force to compel Georgia to join the CIS, although the empirical evidence underlying this interpretation is certainly debatable. We appreciate the remark of an anonymous referee who noted the existence of this case.

We do not include agreements from other areas into our analysis: however, these areas (e.g., inter-parliamentary cooperation) are of minor importance and produce an insignificantly small number of agreements.

All of the acts of the CIS that have been signed by CIS members (or passed by any CIS institution, which all possess an intergovernmental nature and operate on the principles of voluntary participation in each decision) have the same de jure binding legal status (although, depending on the laws of individual CIS countries, certain of these acts may require different forms of ratification). These acts refer to very different types of decisions, such as the establishment of new norms; the specification of budget contributions and allocations of funds; and personnel decisions. However, it is virtually impossible to rank these acts in terms of importance. Personnel decisions, for example, may play a crucial role in affecting the ability of Russia, the leading state of the CIS, to manipulate the organization, and greater disagreements have frequently arisen among the CIS states with respect to these decisions than with respect to more general treaties.

Although it is reported that Georgia requested permission to continue participating in certain CIS agreements (Mikhailenko 2011).

During certain time periods Russia has been more democratic than the remaining members of the CIS (see debate in Obydenkova and Libman 2012), whereas during other periods, it became less democratic than other CIS members.

Unless otherwise stated, these data are derived from the World Development Indicators.

More specifically, we set the dummy equal to 1 if the country was part of the WTO in the last year of a particular 5-year period; we also use the same convention for our robustness checks.

Unfortunately, the quality of data for this metric is rather low. Typically, data on ethnic composition are collected as part of census data; however, these census data are often not sufficiently precise to address the complex issues of ethnic identification and they may suffer from misreporting. In addition, all countries do not implement their censuses in a timely fashion. Finally, because a census is typically administered only once per decade, only 1 to 3 census observations are available for most of the examined post-Soviet states for the examined time period. Thus, we set both of these variables to be equal to the latest possible census data that are available for a particular period.

Details regarding all of the robustness checks that are not presented in the main text of the paper are available in the Supplementary Material.

We should note that the interpretation of the interaction term in non-linear models can be subject to difficulties (Ai and Norton 2003). In linear models (OLS), this interpretation should be conducted based not only on the magnitude and significance of the interaction term but also on the analysis of the changes in the direction, magnitude and significance of marginal effects, as described in Brambor et al. (2006). We follow this approach, plotting the marginal effects; the appropriate graphs are provided in the Supplementary Material.

The variable was constructed in the following way. For Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, we used the average share of CIS oil exports that were reported by the CIS Interstate Statistical Committee. If no information was available regarding this metric for a particular period, then data from the previous period or from the closest subsequent period were used. For all other countries, the share was set to zero. We had to drop Turkmenistan from this examination because no information was available regarding this nation’s oil exports during the examined time period. We also excluded Russia from consideration because of its special status in the system of CIS pipelines.

We also used a different approach in which we estimated regressions for the full sample, but relaxed the assumptions of the initial model, allowing for policy-area-specific slopes. The results of this procedure are discussed in the Supplementary Material.

References

Abdelal, R. (2001). National purpose in the world economy: Post-soviet states in comparative perspective. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80, 123–129.

Allison, P. D., & Waterman, R. P. (2002). Fixed effects negative binomial regression models. Sociological Methodology, 32, 247–265.

Allison, R. (2008). Virtual regionalism, regional structures and regime security in central Asia. Central Asian Survey, 27, 185–202.

Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J. A., Limongi, F., & Przeworski, A. (1996). Classifying political regimes. Studies in Comparative International Development, 31, 3–36.

Ambrosio, T. (2006). The political success of Russia-Belarus relations: Insulating minsk from a ‘Color’ revolution. Demokratizatsiya, 14, 407–434.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., & Smith, A. (2012). Domestic explanations of international relations. Annual Review of Political Science, 15, 161–181.

de Mesquita, B., Bruce, M., James, D., Siverson, R. M., & Smith, A. (1999). An institutional explanation of the democratic peace. American Political Science Review, 93, 791–807.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (1998). Regression analysis of count data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, D. R., & Orenstein, M. A. (2012). Post-soviet authoritarianism: The influence of Russia in its near abroad. Post-Soviet Affairs, 28, 1–44.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2009). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143, 67–101.

Collins, K. (2009). Economic and security regionalism among patrimonial authoritarian regimes: The case of central Asia. Europe-Asia Studies, 61, 249–281.

Darden, K. A. (2009). Economic liberalism and its rivals: The formation of international institutions among the post-soviet states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doner, R. F., Ritchie, B. K., & Slater, D. (2005). Systemic vulnerability and the origins of developmental states: Northeast and Southeast Asia in comparative perspective. International Organization, 59, 327–361.

Dreher, A., & Jensen, N. M. (2007). Independent Actor or Agent? An Empirical Analysis of the Impact of U.S. Interests on International Monetary Fund Conditions. Journal of Law and Economics, 50, 105–124.

Dreher, A., & Voigt, S. (2011). Does Membership in International Organizations Increase Government Credibility? Testing the Effect of Delegating Powers. Journal of Comparative Economics, 39, 326–348.

Fang, S., & Owen, E. (2011). International Institutions and Credible Commitments of Non-Democracies. The Review of International Organizations, 6, 141–162.

Fearon, J. D. (1994). Domestic Political Audiences and the Escalation of International Disputes. American Political Science Review, 88, 577–692.

Gel’man, V. (2012). “Subervsive Institutions and Informal Governance in Contemporary Russia”, in International Handbook on Informal Governance, eds. Thomas Christiansen and Christine Neuhold. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hale, H. E. (2008). The foundations of ethnic politics: Separatism of states and nations in eurasia and the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hausman, J., Hall, B. H., & Griliches, Z. (1984). Econometric models for count data with an application to the Patents-R&D relationship. Econometrica, 52, 909–938.

Hellman, J. S. (1998). Winners take all: The politics of partial reform in postcommunist transitions. World Politics, 50, 203–234.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 347–61.

Kubicek, P. (2009). The commonwealth of independent states: An example of failed regionalism? Review of International Studies, 35, 237–256.

Lankina, T., & Getachew, L. (2006). A geographic incremental theory of democratization: Territory, aid, and democracy in postcommunist regions. World Politics, 58, 536–582.

Libman, A. (2007). Regionalization and regionalism in the post-soviet space: current status and implications for institutional development. Europe-Asia Studies, 59, 401–430.

Libman, A., & Vinokurov, E. (2012). Holding-together regionalism: Twenty years of post-soviet integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Malfliet, K., Verpoest, L., & Vinokurov, E. (Eds.). (2007). The CIS, the EU and Russia: Challenges of integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Mansfield, E. D., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2006). Democratization and international organizations. International Organization, 60, 137–167.

Mansfield, E. D., & Pevehouse, J. C. (2008). Democratization and the Varieties of International Organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 52, 269–294.

Mikhailenko, A. (2011): “Tendencii Postsovetskoi Integracii.” Svobodnaya Mysl (12)

Miller, E. A. (2006). To balance or not to balance: Alignment theory and the commonwealth of independent states. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Obydenkova, A. (2011). Multi-Level Governance in Post-Soviet Eurasia: Problems and Promises. In H. Enderlein, S. Walti, & M. Zuern (Eds.), Handbook on multi-level governance (pp. 292–308). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Obydenkova, A. (2008). Regime transition in the regions of Russia: The freedom of mass media: Transnational impact on sub-national democratization? European Journal of Political Research, 47, 221–246.

Obydenkova, A. (2012). Democratization at the grassroots: The European Union’s external impact. Democratization, 19, 230–257.

Obydenkova, A., & Libman, A. (2012). The impact of external factors on regime transition: Lessons from the Russian regions. Post-Soviet Affairs, 28, 346–401.

Pevehouse, J. C. (2002). With a little help from my friends? Regional organizations and the consolidation of democracy. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 611–626.

Remmer, K. L. (1998). Does democracy promote interstate cooperation? Lessons from the Mercosur region. International Studies Quarterly, 42, 25–51.

Rose, R., & Munro, N. (2008). Do Russians see their future in Europe the CIS? Europe-Asia Studies, 60, 49–66.

Snidal, D., & Thompson, A. (2003). International Commitments and Domestic Politics. Institutions and Actors at Two Levels. In D. W. Drezner (Ed.), Locating the proper authorities. The interaction of domestic and international institutions. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Stone, R. W. (2002). Lending credibility: The international monetary fund and the post-communist transition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stone, R. W. (2004). The political economy of IMF lending in Africa. American Political Science Review, 98, 577–591.

Stone, R. W. (2008). The Scope of IMF Conditionality. International Organization, 62, 589–620.

Stone, R. W. (2011). Controlling institutions: International organizations and the global economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tomz, Michael, Wittenberg, Jason, and Garry King (2003): “CLARIFY: Software for Interpreting and Presenting Statistical Results.” Mimeo

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to their universities, the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management and the Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Barcelona). They would also like to thank both the Ramon y Cajal program of the Ministry of Innovation and Science of Spain (Madrid) and the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad de Gobierno de España for financing the project “Influencias Externas y Democratización: ¿Eurasia contra La Unión Europea?” We are also grateful to Randall W. Stone, the guest editor of this special issue, for his insightful comments on our paper and to three anonymous reviewers of the journal for their very important suggestions and recommendations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(ZIP 945 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Libman, A., Obydenkova, A. Informal governance and participation in non-democratic international organizations. Rev Int Organ 8, 221–243 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-012-9160-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-012-9160-y