Abstract

This paper provides a formal theory of inflectional periphrasis, the phenomenon where a multi-word expression plays the grammatical role normally played by a single word filling a cell in an inflectional paradigm. Expanding on the literature, I first identify and illustrate six key properties that a satisfactory theory of periphrasis should account for: (i) the phenomenon of periphrasis is found in the inflection of all major parts of speech; (ii) the logic of the opposition between periphrasis and synthesis is the logic of inflection; (iii) auxiliaries as used in periphrases are morphosyntactic hybrids; (iv) some periphrases are morphosyntactically non-compositional; (v) periphrasis is independent of phrase structure, but (vi) the parts of a periphrase are linked by a grammatical function. The rest of the paper presents a lexicalist theory of periphrasis, relying on a version of HPSG (Pollard and Sag 1994) for syntax combined with a version of Paradigm Function Morphology (Stump 2001) for inflection. The leading idea is that periphrases are similar to syntactically flexible idioms; the theory of periphrasis is thus embedded within a more general theory of collocation. Periphrasis is accounted for in a strictly lexicalist fashion by recognizing that exponence may take the form of the addition of collocational requirements. I show how the theory accounts for all key properties identified in the first section, deploying partial analyses for periphrastic constructions in English, French, Czech, and Persian.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Notice that I use periphrasis, a mass term, to designate the general phenomenon, and periphrase, a count term, to refer to particular instances of the phenomenon (that is, particular periphrastic constructions).

Note that I use morphosyntactic feature where Brown et al. (2012) say grammatical feature. Also note that this definition makes the identification of periphrasis dependent on the definition of morphosyntactic features, and limits the attention to inflection. I thus leave aside the issue of periphrastic lexeme formation, on which see Ackerman and Webelhuth (1998, 219–340), Ackerman et al. (2011), and Lee and Ackerman (submitted).

Some adjectives also inflect for number and/or gender. Gender agreement is marked by the prefixes d-, b-, j- and v-. The superlative is formed by combining a comparative adjective with the preposed word eggara ‘(the) most’. Nouns distinguish 4 case values, but all non-nominative cases are syncretic on adjectives. This syncretic case value is noted as obl in the glosses.

If more than two exponents are in complementary distribution, the three situations may combine in various ways.

The present perfect is syncretic with the bounded past indirect evidential, and historically based on the morphologization of the clitic form of the copula. However the present perfect forms exhibit a cohesiveness that is not found in copular constructions based on the clitic copula, and present idiosyncratic morphophonological fusion in colloquial usage; hence, despite their historical source, they are clearly synchronically synthetic words. See Bonami and Samvelian (2015) for details.

Corbett (2013, 172) cites the suppletive paradigm of the verb ‘go’ in the Romanian dialect of Fundătura documented by Maiden (2004, 242), which exhibits a morphomic split along the N-pattern between inherent reflexive forms such as 1sg

and nonreflexive forms such as 1pl

and nonreflexive forms such as 1pl

. However this is not a clearcut case, since Romanian reflexive markers have been argued to be affixal (Monachesi 2005).

. However this is not a clearcut case, since Romanian reflexive markers have been argued to be affixal (Monachesi 2005).This table is unfaithful to Chumakina’s description in two respects. First, Chumakina points out that a periphrastic realization is also possible for the present habitual, although it is dispreferred. Second, Chumakina labels ‘past perfective’ the forms labeled here as ‘past perfect’, and takes the present/past distinction to be irrelevant for the form labeled here ‘present perfect’; in addition the form labeled here ‘bounded past’ is labeled ‘simple past’, and my ‘unbounded’ forms are ‘imperfective’. This slightly different view of the data does not affect the point that neither the synthetic nor the periphrastic strategy covers a natural class of paradigm cells: quite on the contrary, by more strongly collapsing the opposition between tense and aspect, Chumakina’s view of the data is even more strikingly morphomic. I am indebted to Marina Chumakina for extended discussion of the issue and for kindly providing the unpublished partial paradigm in Table 6.

Czech nouns inflect for 2 numbers and 7 cases. In the interest of space, Table 7 only shows 4 case values.

In the Czech grammatical tradition, the class of kuře is treated as a separate inflection class, under the assumption of a segmentation where the stem is constant and the -et-, -at- augments are part of inflection. A more satisfactory analysis, which is hinted at in Cvrček et al. (2010, 189), is to assume that these augments are segmented separately, either as portion of stem alternants or as separate suffixes.

See Cvrček et al. (2010, 167). I am indebted to Jana Strnadová for extended discussion of the Czech data.

The symbol ‘∼’ notes free variation. In the nominative and accusative, there is no contrast between the masculine inanimate hard and soft declensions, and hence no variation in form.

The head and edge situations are far from exhausting the typology of loci of realization of morphosyntactic properties. A spectacular example in Persian is discussed by Samvelian and Tseng (2010), where pronominal complements of a verb are realized on the edge of its least oblique remaining complement, irrespective of the position of that complement in the clause.

This discussion presupposes that the determination of the head of the relevant construction can be made independently of the morphological expression of phrasal properties, by the sole examination of the syntactic distribution of the ancillary and main elements. Of course in many instances the relevant evidence is partial or lacking. Note the contrast between our and Gregory Anderson’s (2006) use of ‘head’: Anderson calls a periphrase aux-headed (resp. lex-headed) if and only if all phrasal properties that are realized inflectionally are realized on the ancillary (resp. main) element.

See Abeillé and Godard (2002) for detailed discussion of the contrasts between these two structures. Importantly, neither structure is reserved for periphrastic inflection: the flat structure is also characteristic of causative constructions, the nested structure is also characteristic of modal verbs.

Up to now I have only discussed cases where the ancillary element is the head and the main element is either the complement or the head of that complement. There are claims in the literature that the opposite situation also arises (Anderson 2006; Brown et al. 2012), with the ancillary element being a dependent and the main element the head. However the empirical evidence presented in support of these claims is not compelling, and amenable to alternative analyses. I leave the exploration of such cases for future research.

In fact, more than two expressions can be involved. I will analyze such a case below.

I am indebted to Farrell Ackerman for pointing out this dataset and its relevance. Periphrastic expression of the future in Persian presents similar problems.

The Persian progressive, discussed in Sect. 2.4, is an example of the limiting case where the main element on its own is compatible with the content expressed by the periphrase. In that case the sole role of the periphrastic combination is the exclusion of other readings—specifically, while the synthetic form on its own is compatible with either a progressive or a habitual reading, the periphrase only conveys the progressive.

This is well known to be a slight idealization, since kick the bucket allows for limited, metalinguistic internal modification in expressions such as kick the proverbial bucket.

A more precise definition of reverse selection in the vocabulary of HPSG can be found in the Appendix.

I follow Bonami and Stump (forthcoming) in assuming that situations where two rules are unordered by specificity while being more specific than all other rules in the block lead to overabundance: there is more than one optimal exponence strategy.

Notice that Bonami and Samvelian (2009) obtain the effect of (38) using a block-internal rule of referral rather than an implicative statement in the definition of the paradigm function. See Bonami and Stump (forthcoming) for a discussion of the differences between these two approaches to directional syncretism.

In the case of statements about synthetic inflection, the set of reverse selection requirements is empty. In that case, in the interest of backwards compatibility, I take the notational liberty to write the output of the paradigm function as a paradigm cell: I write ‘〈φ,σ〉’ for what should really be ‘〈〈φ,σ〉,∅〉’.

Implicit in (40a) is an analysis of synthetic inflection relying on 3 rule blocks for superlative prefixes, comparative suffixes, and case/number suffixes. The slightly simplified analysis sketched here does not capture the common properties of periphrastic comparatives and superlatives. Doing so entails treating comparatives and superlatives as sharing a common morphosyntactic property.

Of course this is only the first step of an adequate account of overabundance. As Boyd (2007) shows, the relative frequency of the synthetic and periphrastic strategies varies considerably from adjective to adjective, with various phonological, morphological, syntactic or lexical factors acting as partial predictors of the observed distribution. Modeling such effects can only be approached within a probabilistic view of grammar.

Technically, the treatment of overabundance proposed in Bonami and Stump (forthcoming) and adopted here entails that paradigm functions output sets of cells. Hence the usual notation involving identity statements of the form ‘PF(l,σ)=X’ is misleading, and would more cogently be replaced by a notation of the form ‘X∈PF(l,σ)’. In the interest of readability and backwards compatibility though, I have refrained from introducing a new notation. However, in Sect. 5, where I will need to refer to the output of the paradigm function rather than individual clauses in its definition, set membership will explicitly be used.

The analysis presented here is simplified in various ways, in the interest of space, notably by not taking into account so-called ‘overcompound’ (‘surcomposé’) forms, or an explicit account of pronominal affix realization on the auxiliary.

The locus of these syntactic features within the sign is variable. All features discussed in exemplification in this paper are head features, that is, features whose value is projected from head to phrase. However it is known that some features realized by inflection need to be considered marking (Tseng 2002a) or edge (Tseng 2002b) features.

An obvious alternative is to implement within HPSG an approach to morphology sharing the main design features of PFM. See Crysmann and Bonami (2012), Bonami and Crysmann (2013) for explicit proposals of this kind. The interface between infl and morphosyntactic property sets could also be seen as the locus of the distinction between content and form paradigms advocated by Stump (2006). I leave aside theses issues which are orthogonal to the concerns of this paper.

References

Abeillé, A., & Godard, D. (2000). French word order and lexical weight. In R. D. Borsley (Ed.), The nature and function of syntactic categories, syntax and semantics (pp. 325–360). New York: Academic Press.

Abeillé, A., & Godard, D. (2002). The syntactic structure of French auxiliaries. Language, 78, 404–452.

Ackerman, F., & Nikolaeva, I. (2014). Descriptive typology and linguistic theory. A study in the morphosyntax of relative clauses. Stanford: CSLI.

Ackerman, F., & Stump, G. T. (2004). Paradigms and periphrastic expression. In L. Sadler & A. Spencer (Eds.), Projecting morphology (pp. 111–157). Stanford: CSLI.

Ackerman, F., Stump, G. T., & Webelhuth, G. (2011). Lexicalism, periphrasis and implicative morphology. In R. D. Borsley & K. Börjars (Eds.), Non-transformational syntax: formal and explicit models of grammar (pp. 325–358). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Ackerman, F., & Webelhuth, G. (1998). A theory of predicates. Stanford: CSLI.

Anderson, G. (2006). Auxiliary verb constructions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, J. M. (2011). The substance of language volume II: morphology, paradigms, and periphrases. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, S. R. (1992). A-morphous morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aronoff, M. (1994). Morphology by itself. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Aronoff, M., & Lindsay, M. (2015). Partial organization in languages: la langue est un système où la plupart se tient. In S. Augendre, G. Couasnon-Torlois, D. Lebon, C. Michard, G. Boyé, & F. Montermini (Eds.), Proceedings of the 8th décembrettes (pp. 1–14). Toulouse: CLLE-ERSS.

Blevins, J. P. (2006). Word-based morphology. Journal of Linguistics, 42, 531–573.

Blevins, J. P. (forthcoming). Periphrasis as syntactic exponence. In F. Ackerman, J. P. Blevins, & G. T. Stump (Eds.), Paradigms and periphrasis. Stanford: CSLI.

Bonami, O., & Crysmann, B. (2013). Morphotactics in an information-based model of realisational morphology. In S. Müller (Ed.), Proceedings of HPSG 2013 (pp. 27–47). Stanford: CSLI.

Bonami, O., & Samvelian, P. (2009). Inflectional periphrasis in Persian. In S. Müller (Ed.), Proceedings of the HPSG 2009 conference (pp. 26–46). Stanford: CSLI.

Bonami, O., & Samvelian, P. (2015). The diversity of inflectional periphrasis in Persian. Journal of Linguistics, 51(2). doi:10.1017/S0022226714000243.

Bonami, O., & Stump, G. T. (forthcoming). Paradigm function morphology. In A. Hippisley & G. T. Stump (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bonami, O., & Webelhuth, G. (2013). The phrase-structural diversity of periphrasis: a lexicalist account. In M. Chumakina & G. G. Corbett (Eds.), Periphrasis: the role of syntax and morphology in paradigms (pp. 141–167). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Booij, G. (2010). Construction morphology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boyd, J. (2007). Comparatively speaking: a psycholinguistic study of optionality in grammar. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, San Diego.

Bresnan, J. (1978). A realistic transformational grammar. In M. Halle, J. Bresnan, & G. A. Miller (Eds.), Linguistic theory and psychological reality (pp. 1–59). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bresnan, J. (2001a). Explaining morphosyntactic competition. In M. Baltin & C. Collins (Eds.), Handbook of contemporary syntactic theory (pp. 11–44). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Bresnan, J. (2001b). Lexical-functional syntax. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Brown, D., Chumakina, M., Corbett, G. G., Popova, G., & Spencer, A. (2012). Defining ‘periphrasis’: key notions. Morphology, 22, 233–275.

Brown, D., & Evans, R. (2012). Morphological complexity and unsupervised learning: validating Russian inflectional classes using high frequency data. In F. Kiefer, M. Ladányi, & P. Siptár (Eds.), Current issues in morphological theory: (ir)regularity, analogy and frequency (pp. 135–162). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Chumakina, M. (2013). Periphrasis in Archi. In M. Chumakina & G. G. Corbett (Eds.), Periphrasis: the role of syntax and morphology in paradigms (pp. 27–52). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Corbett, G. G. (2013). Periphrasis and possible lexemes. In M. Chumakina & G. G. Corbett (Eds.), Periphrasis: the role of syntax and morphology in paradigms (pp. 169–189). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Corbett, G. G. (in press). Morphosyntactic complexity: a typology of lexical splits. Language.

Crysmann, B., & Bonami, O. (2012). Establishing order in type-based realisational morphology. In S. Müller (Ed.), Proceedings of HPSG 2012 (pp. 123–143). Stanford: CSLI.

Cvrček, V., Kodýtek, V., Kopřivová, M., Kováříková, D., Sgall, P., Šulc, M., Táborký, J., Volín, J., & Waclawičová, M. (2010). Mluvince sousčasné češtiny (Vol. 1). Prague: Karolinum.

Fillmore, C. J., Kay, & O’Connor, M. C. (1988). Regularity and idiomaticity in grammatical constructions: the case of let alone. Language, 64, 501–538.

Franks, S., & Holloway King, T. (2000). A handbook of Slavic clitics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gazdar, G. (1982). Phrase structure grammar. In P. Jacobson & G. K. Pullum (Eds.), The nature of syntactic representations. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Gazdar, G., Klein, E., Pullum, G. K., & Sag, I. A. (1985). Generalized phrase structure grammar. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Ginzburg, J., & Sag, I. A. (2000). Interrogative investigations. The form, meaning, and use of English interrogatives. Stanford: CSLI.

Gonzalez-Diaz, V. (2008). English adjective comparison: a historical perspective. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Göskel, A., & Kerslake, C. (2005). Turkish: a comprehensive grammar. Oxon: Routledge.

Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1993). Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In K. Hale & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from building 20 (pp. 111–176). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halpern, A. (1995). On the placement and morphology of clitics. Stanford: CSLI.

Harman, G. H. (1963). Generative grammars without transformation rules. A defense of phrase structure. Language, 39, 597–616.

Haspelmath, M. (2000). Periphrasis. In G. Booij, C. Lehmann, & J. Mugdan (Eds.), Morphology: an international handbook on inflection and word-formation (Vol. 1, pp. 654–664). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Hippisley, A. (2007). Declarative deponency: a network morphology account of morphological mismatches. In M. Baerman, G. G. Corbett, D. Brown, & A. Hippisley (Eds.), Deponency and morphological mismatches (pp. 145–173). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hockett, C. F. (1958). A course in modern linguistics. New York: Macmillan.

Hockett, C. F. (1967). The Yawelmani basic verb. Language, 43, 208–222.

Horn, G. M. (2003). Idioms, metaphor, and syntactic mobility. Journal of Linguistics, 39, 245–273.

Huddleston, R., & Pullum, G. K. (2002). The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, D., & Lappin, S. (1999). Local constraints vs. economy. Stanford: CSLI.

Karlík, P., Nekula, M., & Rusínová, Z. (1995). Příruční mluvnice češtiny. Prague: Lidové Noviny.

Kiparsky, P. (1973). ‘Elsewhere’ in phonology. In S. R. Anderson & P. Kiparsky (Eds.), A Festschrift for Morris Halle (pp. 93–106). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Kiparsky, P. (2005). Blocking and periphrasis in inflectional paradigms. In G. Booij & J. v. Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology 2004 (pp. 113–135). Dordrecht: Springer.

Kuhn, J. (2003). Optimality-theoretic syntax: a declarative approach. Stanford: CSLI.

Lee, L., & Ackerman, F. (submitted). Thai passives and the morphology–syntax interface. UCSD.

Legendre, G. (2007). On the typology of auxiliary selection. Lingua, 117, 1522–1540.

Maiden, M. (1992). Irregularity as a determinant of morphological change. Journal of Linguistics, 28, 285–312.

Maiden, M. (2004). When lexemes become allomorphs—on the genesis of suppletion. Folia Linguistica, 38, 227–256.

Malouf, R. (2003). Cooperating constructions. In E. Francis & L. A. Michaelis (Eds.), Linguistic mismatch: scope and theory (pp. 403–424). Stanford: CSLI.

Matthews, P. H. (1972). Inflectional morphology. A theoretical study based on aspects of Latin verb conjugation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Matthews, P. H. (1991). Morphology (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mel’čuk, I. A. (1993). Introduction et première partie: Vol. 1. Cours de morphologie générale. Montréal & Paris: Presses de l’Université de Montréal & CNRS Éditions.

Miller, P. (1992). Clitics and constituents in phrase structure grammar. New York: Garland.

Monachesi, P. (2005). The verbal complex in Romance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Müller, S. (2002). Complex predicates: verbal complexes, resultative constructions, and particle verbs in German. Stanford: CSLI.

Müller, S. (2010). Persian complex predicates and the limits of inheritance-based analyses. Journal of Linguistics, 46, 601–655.

Müller, S. (2013). Unifying everything: some remarks on simpler syntax, construction grammar, minimalism, and HPSG. Language, 89, 920–950.

Nichols, J. (2011). Ingush grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nikolaeva, I. (2013). Periphrasis in Tundra Nenets. In M. Chumakina & G. G. Corbett (Eds.), Periphrasis: the role of syntax and morphology in paradigms (pp. 77–104). London/Oxford: British Academy/Oxford University Press.

Nikolaeva, I. (2014). A grammar of Tundra Nenets. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Nunberg, G., Sag, I. A., & Wasow, T. (1994). Idioms. Language, 70, 491–538.

Pollard, C., & Sag, I. A. (1987). Information-based syntax and semantics. Stanford: CSLI.

Pollard, C., & Sag, I. A. (1994). Head-driven phrase structure grammar. Stanford: CSLI/The University of Chicago Press.

Popova, G., & Spencer, A. (2013). Relatedness in periphrasis: a paradigm-based perspective. In M. Chumakina & G. G. Corbett (Eds.), Periphrasis: the role of syntax and morphology in paradigms (pp. 191–225). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Poser, W. J. (1992). Blocking of phrasal constructions by lexical items. In I. A. Sag & A. Szabolcsi (Eds.), Lexical matters (pp. 111–130). Stanford: CSLI.

Richter, F., & Sailer, M. (2003). Cranberry words in Formal grammar. In C. Beyssade, O. Bonami, P. Cabredo Hofherr, & F. Corblin (Eds.), Empirical issues in formal syntax and semantics (Vol. 4, pp. 155–171). Paris: Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne.

Richter, F., & Sailer, M. (2010). Phraseological clauses in constructional HPSG. In Proceedings of HPSG 2009 (pp. 297–317). Stanford: CSLI.

Richter, F., & Soehn, J.-P. (2006). Braucht niemanden zu scheren—NPI licensing in German. In S. Müller (Ed.), Proceedings of HPSG 2006 (pp. 421–440). Stanford: CSLI.

Robins, R. H. (1959). In defense of WP. In Transactions of the philological society (pp. 116–144).

Sadler, L., & Spencer, A. (2001). Syntax as an exponent of morphological features. In G. Booij & J. van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology 2000 (pp. 71–96). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Sag, I. A. (2012). Sign-based construction grammar: an informal synopsis. In H. Boas & I. A. Sag (Eds.), Sign-based construction grammar (pp. 69–202). Stanford: CSLI.

Sailer, M. (2000). Combinatorial semantics and idiomatic expressions in head-driven phrase structure grammar. Ph.D. thesis, Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen.

Salminen, T. (1997). Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne: Vol. 227. Tundra Nenets inflection. Helsink: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

Samvelian, P., & Tseng, J. (2010). Persian object clitics and the syntax-morphology interface. In Proceedings of HPSG 2010 (pp. 212–232). Stanford: CSLI.

Short, D. (1993). Czech. In B. Comrie & G. G. Corbett (Eds.), The Slavonic languages (pp. 455–532). London: Routledge.

Soehn, J.-P. (2006). Über Bärendienste und erstaunte Bauklötze—Idiome ohne freie Lesart in der HPSG. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Soehn, J.-P., & Sailer, M. (2003). At first blush on Tenterhooks. About selectional restrictions imposed by nonheads. In G. Jäger, P. Monachesi, G. Penn, & S. Wintner (Eds.), Proceedings of Formal grammar 2003 (pp. 123–138).

Sorace, A. (2000). Gradients in auxiliary selection with intransitive verbs. Language, 76, 859–890.

Spencer, A. (2003). Periphrastic paradigms in Bulgarian. In U. Junghanns & L. Szucsich (Eds.), Syntactic structures and morphological information (pp. 249–282). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Spencer, A. (2013a). Lexical relatedness: a paradigm-based model. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spencer, A. (2013b). Sentence negation and periphrasis. In M. Chumakina & G. G. Corbett (Eds.), Periphrasis: the role of syntax and morphology in paradigms (pp. 227–266). London/Oxford: British Academy/Oxford University Press.

Steedman, M. (1996). Surface structure and interpretation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Stump, G. T. (2001). Inflectional morphology. A theory of paradigm structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stump, G. T. (2002). Morphological and syntactic paradigms: arguments for a theory of paradigm linkage. In G. Booij & J. van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology 2001. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Stump, G. T. (2006). Heteroclisis and paradigm linkage. Language, 82, 279–322.

Stump, G. T. (2013). Periphrasis in the Sanskrit verb system. In M. Chumakina & G. G. Corbett (Eds.), Periphrasis (pp. 105–138). London/Oxford: British Academy/Oxford University Press.

Stump, G. T., & Hippisley, A. (2011). Valence sensitivity in Pamirian past-tense inflection: a realizational analysis. In A. Korn, G. Haig, S. Karimi, & P. Samvelian (Eds.), Topics in Iranian linguistics (pp. 103–116). Wiesbaden: Ludwig Riechert Verlag.

Thornton, A. M. (2012). Reduction and maintenance of overabundance. A case study on Italian verb paradigms. Word Structure, 5, 183–207.

Tseng, J. (2002a). Remarks on marking. In F. Van Eynde, L. Hellan, & D. Beermann (Eds.), The proceedings of the 8th international conference on head-driven phrase structure grammar (pp. 267–283). Stanford: CSLI.

Tseng, J. L. (2002b). Edge features and French liaison. In J.-B. Kim & S. Wechsler (Eds.), The proceedings of the 9th international conference on head-driven phrase structure grammar (pp. 313–333). Stanford: CSLI.

Vincent, N., & Börjars, K. (1996). Suppletion and syntactic theory. In Proceedings of the first LFG conference.

Wagner-Nagy, B. (2011). On the typology of negation in Ob-Ugric and Samoyedic languages. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

Walther, G. (2013). De la canonicité en morphologie: perspective empirique, théorique et computationnelle. Ph.D. thesis, Université Paris Diderot.

Wasow, T., Sag, I. A., & Nunberg, G. (1984). Idioms: an interim report. In S. Hattori & K. Inoue (Eds.), Proceedings of the XIIIth international congress of linguists (pp. 102–115). Tokyo: Nippon Toshi Center.

Webelhuth, G., Bargmann, S., & Götze, C. (forthcoming). Idioms as evidence for the proper analysis of relative clauses. In M. Krifka, R. Ludwig, & M. Schenner (Eds.), Reconstruction effects in relative clauses. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Wheeler, M. W. (1979). The phonology of Catalan. Oxford: Blackwell.

Zwicky, A. M. (1992). Some choices in the theory of morphology. In R. D. Levine (Ed.), Formal grammar. Theory and implementation (pp. 327–371). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

This paper started out as an elaboration of Bonami and Webelhuth (2013), designed jointly with Gert Webelhuth and presented at the eighth Mediterranean Morphology Meeting (Cagliary, september 2011) and at the first Frankfurt HPSG workshop (May 2012). I thank the audience at these events for their comments and suggestions. Although Gert Webelhuth could not participate in the writing of this paper and insisted on not co-signing it, his influence on its content is considerable. For providing expert help, and often data, on various languages, I thank Farrell Ackerman (Tundra Nenets), Marina Chumakina (Archi), Johanna Nichols (Ingush), and Jana Strnadová (Czech). Discussions on idioms with Sascha Bargmann were also very helpful. Farrell Ackerman, Berthold Crysmann, Philip Miller, Andrew Spencer and Gert Webelhuth provided important feedback on pre-final versions, leading to many improvements. Any remaining errors are of course my own.

This work was written as the author was a member of the Institut Universitaire de France. It was partially supported by a public grant overseen by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the “Investissements d’Avenir” program (reference: ANR-10-LABX-0083).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: A statement of reverse selection

Appendix: A statement of reverse selection

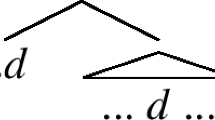

The notion of reverse selection has been characterized informally in Sect. 3.2. Here I provide a partial formalization of the notion in the context of HPSG. The following definitions assume a standard post-Pollard and Sag (1994) feature geometry, with selection of subjects, specifiers and complements via the feature arg-st and selection of heads by adjuncts via the feature mod.

It will be assumed that lexical signs possess a specific representation lex outside of synsem that collects various features that are only indirectly represented in syntax, including arg-st and the syntactic and infl features discussed above. Reverse selection is enacted through a set-valued feature rev-sel inside lex. I assume that elements of rev-sel are of type infl, because I have not encountered situations where more information needs to be referred to via reverse selection. However nothing crucial hinges on this choice.

Reverse selection can be stated as a principle constraining rev-sel requirements to be met in the immediate environment:

-

(54)

Projection

-

a.

Every sign is a projection of itself.

-

b.

A phrase is a projection of its head.

-

c.

A coordination is a projection of each of its daughters.

-

a.

-

(55)

Selection

-

a.

A sign selects all signs whose local value is identical to that of an element on its arg-st.

-

b.

A sign selects any sign whose local value is identical to that of an element on its mod.

-

a.

-

(56)

Reverse Selection Principle If a word w carries a reverse selection requirement s in its rev-sel, then s must be token-identical to the infl value of a word w′ selecting for a projection of w.

As stated, the Reverse Selection Principle will ensure that the main element in a periphrase must appear in the syntactic dependency of the ancillary element. However this is not quite sufficient to avoid overgeneration: the ancillary element may still be found in combination with a sign that is not reverse-selecting for it. Although this situation could be avoided by the addition of control features, it is more elegant to rule it out as a matter of principle. This is the intent of the following principle.

-

(57)

All words belong to one of the three types simple-word, main-word and ancillary-word.

-

(58)

Ancillary element licensing Any word of type ancillary-word must be licensed by the presence in the same utterance of a main-word whose rev-sel contains an element token-identical with the ancillary-word’s infl value.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bonami, O. Periphrasis as collocation. Morphology 25, 63–110 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-015-9254-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-015-9254-3

and nonreflexive forms such as

and nonreflexive forms such as  . However this is not a clearcut case, since Romanian reflexive markers have been argued to be affixal (Monachesi

. However this is not a clearcut case, since Romanian reflexive markers have been argued to be affixal (Monachesi