Abstract

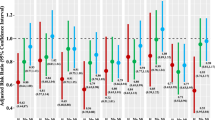

Preterm delivery (PTD), or birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation, is a serious public health issue, and racial disparities persist. In a recently published study, perceptions of the residential environment (or neighborhood context) were associated with PTD rates among urban African American women with low educational attainment (≤12 years); however, the mechanisms of these associations are unknown. Given this gap in the literature, we used data from the Life Influences on Fetal Environments Study of postpartum African American women from Metropolitan Detroit, Michigan (2009–2011; n = 399), to examine whether psychosocial factors (depressive symptomology, psychological distress, and perceived stress) mediate associations between perceptions of the neighborhood context and PTD. Validated scales were used to measure women’s perceptions of their neighborhood safety, walkability, healthy food availability (higher=better), and social disorder (higher=more disorder). The psychosocial indicators were measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale, Kessler’s Psychological Distress Scale (K6), and Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale. Statistical mediation was assessed using an unadjusted logistic regression-based path analysis for estimating direct and indirect effects. The associations between perceived walkability, food availability, and social disorder were not mediated by psychosocial factors. However, perceptions of neighborhood safety were inversely associated with depressive symptoms which were positively associated with PTD rates. Also, higher perceived neighborhood social disorder was associated with higher PTD rates, net of the indirect paths through psychosocial factors. Future research should identify other mechanisms of the perceived neighborhood context-PTD associations, which would inform PTD prevention efforts among high-risk groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008; 371(9606): 75–84.

CDC. Reproductive Health: Preterm Birth. 2013; http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/MaternalInfantHealth/PretermBirth.htm. Accessed April 26, 2013.

Martin J, Hamilton B, Osterman M, Curtin S, Matthews T. Births: Final Data for 2012. National Vital Statistics Reports; Volume 62 Number 9. Vol 62 No 9. Hyattsville, MD: U.S Department of Health & Human Services; 2013.

National Center for Health Statistics, first natality data. 2015; http://www.marchofdimes.org/Peristats/ViewSubtopic.aspx?reg=99&top=3&stop=63&lev=1&slev=1&obj=1. Accessed 8 Dec 2015.

Osypuk TL, Galea S, McArdle N, Acevedo-Garcia D. Quantifying separate and unequal: racial-ethnic distributions of neighborhood poverty in Metropolitan America. Urban Aff Rev. 2009; 45(1): 25–65.

Logan J, Stults B. Separate and Unequal: the Neighborhood Gap for Blacks, Hispanics and Asians in Metropolitan America. Providence, RI: Russell Sage Foundation and The American Communities Project of Brown University; 2011.

Dole N, Savitz DA, Siega-Riz AM, Hertz-Picciotta I, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Psychosocial factors and preterm birth among African American and white women in central North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94(8): 1358–1365.

Giurgescu C, Zenk SN, Dancy BL, Park CG, Dieber W, Block R. Relationships among neighborhood environment, racial discrimination, psychological distress, and preterm birth in African American women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012; 41(6): E51–E61.

Sealy-Jefferson S, Giurgescu C, Helmkamp L, Misra DP, Osypuk TL. Perceived physical and social residential environment and preterm delivery in African-American women. Am J Epidemiol. 2015; 182(6): 485–493.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Seeing disorder: neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows”. Soc Psychol Q. 2004; 67(4): 319–342.

Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001; 42(3): 258–276.

Schulz A, Williams D, Israel B, et al. Unfair treatment, neighborhood effects, and mental health in the Detroit metropolitan area. J Health Soc Behav. 2000; 41(3): 314–332.

Hill TD, Ross CE, Angel RJ. Neighborhood disorder, psychophysiological distress, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2005; 46(2): 170–186.

Gary TL, Stark SA, LaVeist TA. Neighborhood characteristics and mental health among African Americans and whites living in a racially integrated urban community. Health & place. 2007; 13(2): 569–575.

Accortt EE, Cheadle AC, Dunkel SC. Prenatal depression and adverse birth outcomes: an updated systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2015; 19(6): 1306–1337.

Dunkel SC. Psychological science on pregnancy: stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011; 62(1): 531–558.

Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2001; 108(2): e35–e35.

Mujahid MS, Diez Roux AV, Morenoff JD, Raghunathan T. Assessing the measurement properties of neighborhood scales: from psychometrics to ecometrics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007; 165(8): 858–867.

Echeverria SE, Diez-Roux AV, Link BG. Reliability of self-reported neighborhood characteristics. J Urban Health. 2004; 81(4): 682–701.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997; 277(5328): 918–924.

Stahl T, Rutten A, Nutbeam D, et al. The importance of the social environment for physically active lifestyle—results from an international study. Soc Sci Med. 2001; 52(1): 1–10.

Orr ST, James SA, Blackmore PC. Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms and spontaneous preterm births among African-American women in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Epidemiol. 2002; 156(9): 797–802.

Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol. 1977; 106(3): 203–214.

Canady RB, Stommel M, Holzman C. Measurement properties of the centers for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D) in a sample of African American and non-Hispanic White pregnant women. J Nurs Meas. 2009; 17(2): 91–104.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977; 1(3): 385–401.

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003; 60(2): 184–189.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983; 24(4): 385–396.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985; 98(2): 310–357.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008; 40(3): 879–891.

Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: a Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013.

Gruenberg DA, Wright RJ, Visness CM, et al. Relation between stress and cytokine responses in inner-city mothers. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015; 115(5): 439–445. e433.

McEwen BS. Brain on stress: how the social environment gets under the skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012; 109(SUPPL.2): 17180–17185.

Peters A, McEwen BS. Introduction for the allostatic load special issue. Physiol Behav. 2012; 106(1): 1–4.

McEwen BS. Stressed or stressed out: what is the difference? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005; 30(5): 315–318.

Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Peters RM, Johnson DA, Templin TN. Association of depressive symptoms with inflammatory biomarkers among pregnant African-American women. J Reprod Immunol. 2012; 94(2): 202–209.

Christian LM, Franco A, Glaser R, Iams JD. Depressive symptoms are associated with elevated serum proinflammatory cytokines among pregnant women. Brain Behav Immun. 2009; 23(6): 750–754.

Coussons-Read ME, Lobel M, Carey JC, et al. The occurrence of preterm delivery is linked to pregnancy-specific distress and elevated inflammatory markers across gestation. Brain Behav Immun. 2012; 26(4): 650–659.

Coussons-Read ME, Okun ML, Schmitt MP, Giese S. Prenatal stress alters cytokine levels in a manner that may endanger human pregnancy. Psychosom Med. 2005; 67(4): 625–631.

Schminkey DL, Groer M. Imitating a stress response: a new hypothesis about the innate immune system’s role in pregnancy. Med Hypotheses. 2014; 82(6): 721–729.

Chatterjee P, Chiasson VL, Bounds KR, Mitchell BM. Regulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 during pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2014; 5: 253.

Giurgescu C, Engeland CG, Zenk SN, Kavanaugh K. Stress, inflammation and preterm birth in African American Women. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews. 2013; 13(4): 171–177.

Gargano JW, Holzman C, Senagore P, et al. Mid-pregnancy circulating cytokine levels, histologic chorioamnionitis and spontaneous preterm birth. J Reprod Immunol. 2008; 79(1): 100–110.

Ruiz RJ, Jallo N, Murphey C, Marti CN, Godbold E, Pickler RH. Second trimester maternal plasma levels of cytokines IL-1Ra, Il-6 and IL-10 and preterm birth. J Perinatol. 2012; 32(7): 483–490.

Vogel I, Goepfert AR, Thorsen P, et al. Early second-trimester inflammatory markers and short cervical length and the risk of recurrent preterm birth. J Reprod Immunol. 2007; 75(2): 133–140.

Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010; 1186.1: 125–145.

Aneshensel CS, Sucoff CA. The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 1996; 37(4): 293–310.

Franzini L, Caughy MOB, Nettles SM, O’Campo P. Perceptions of disorder: contributions of neighborhood characteristics to subjective perceptions of disorder. J Environ Psychol. 2008; 28(1): 83–93.

Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Wiley; 2008.

Radloff LS, Locke BZ. The Community Mental Health Assessment Survey and CES-D Scale. In: Weissman MM, J.K. M, eds. Community Surveys of Psychiatric Disorders. eds. ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1986:177-189.

Orr ST, Blazer DG, James SA, Reiter JP. Depressive symptoms and indicators of maternal health status during pregnancy. J Women’s Health. 2007; 16(4): 535–542.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by a grant from National Institutes of Health #1F32HD080338.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Michigan, St. John Providence Health System, and Wayne State University. All study participants gave written informed consent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sealy-Jefferson, S., Giurgescu, C., Slaughter-Acey, J. et al. Neighborhood Context and Preterm Delivery among African American Women: the Mediating Role of Psychosocial Factors. J Urban Health 93, 984–996 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0083-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0083-4