Abstract

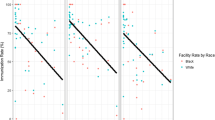

Racial disparities in invasive pneumococcal disease and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination (PPV) persist despite significant progress. One reason may be that minority patients receive primary care at practices with fewer resources, less efficient office systems, and different priorities. The purposes of this paper are: (1) to describe the recruitment of a diverse array of primary care practices in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania serving white and minority patient populations, and the multimodal data collection process that included surveys of key office personnel, observations of practice operations and medical record reviews for determining PPV vaccination rates; and (2) to report the results of the sampling strategy. During 2005, 18 practices participated in the study, six with a predominantly minority patient population, nine with a predominantly white patient population, and three with a racial distribution similar to that of this locality. Eight were solo practices and 10 were multiprovider practices; they included federally qualified health centers, privately owned practices and faculty and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center community practices. Providers represented several racial and ethnic groups, as did office staffs. PPV rates determined from 2,314 patients’ medical records averaged 60.3 ± 22.6% and ranged from 11% to 97%. Recruitment of practices with attention to location, patient demographics, and provider types results in a diverse sample of practices and patients. Multimodal data collection from these practices should provide a rich data source for examining the complex interplay of factors affecting immunization disparities among older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2006 National Health Interview Survey. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhis/released200706.htm. 2007. Accessed on August 20, 2007.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—National Center for Health Statistics. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the January–September 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhis/released200603.htm#4. 2006.

Kyaw MH, Rose CE Jr, Fry AM, et al. The influence of chronic illness on the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in adults. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:377–386.

Lexau CA, Lynfield R, Danila R, et al. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among older adults in the era of pediatric pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294:2043–2051.

Flannery B, Schrag S, Bennett NM, et al. Impact of childhood vaccination on racial disparities in invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;291:2197–2203.

Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:575–584.

Gyorkos TW, Tannenbaum TN, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of immunization delivery methods. Can J Public Health. 1994;85:S14–S30.

Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:92–96.

Lin MK, Marsteller JA, Shortell SM, et al. Motivation to change chronic illness care: results from a national evaluation of quality improvement collaboratives. Health Care Manage Rev. 2005;30:139–156.

Zammuto RF, Krakower JY. Quantitative and qualitative studies of organizational culture. Res Organ Change Dev. 1991;5:83–114.

Shortell SM, Marsteller JA, Lin M, et al. The role of perceived team effectiveness in improving chronic illness care. Med Care. 2004;42:1040–1048.

Aday LA. Designing and Conducting Health Surveys. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.; 1989.

Bryk A, Raudenbush S. Hierarchical Linear Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1992.

Boyd AD, Hosner C, Hunscher DA, Athey BD, Clauw DJ, Green LA. An ‘Honest Broker’ mechanism to maintain privacy for patient care and academic medical research. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76:407–411.

Silverman M, Terry MA, Zimmerman RK, Nutini JF, Ricci EM. The role of qualitative methods for investigating barriers to adult immunization. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:1058–1075.

Silverman M, Terry MA, Zimmerman RK, Nutini JF, Ricci EM. Tailoring interventions: understanding medical practice culture. J Cross-Cult Gerontol. 2004;19:47–76.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000.

Krieger N, Rowley DL, Herman AA, Avery B, Phillips MT. Racism, sexism and social class: implications for studies of health, disease, and well-being. Am J Prev Med. 1993;9:82–122.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Pascale M. Wortley, PhD from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for her invaluable advice in the preparation of this manuscript.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Grant No. 5 U01 IP000054-02 and the National Institutes of Health and the EXPORT Health Project at the Center for Minority Health, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, NIH/NCMHD Grant No. P60 MD-000-207. Its contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the CDC, ATPM, or the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Zimmerman, Nowalk, Raymund, Tabbarah, and Fox are with the Department of Family Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; Zimmerman and Terry are with the Department of Behavioral and Community Health Sciences, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; Wilson is with the UPMC St. Margaret Family Medicine Residency, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Sampling Scheme

A proportional random cluster sample will be conducted to achieve about 165 patients per practice, nested by clinician.

-

Step 1.

Site or UPMC will develop list of names of persons aged 65 or older seen in the last year as outpatients. We will assume N patients appear on the list. Inpatient visits are not to be included.

-

Step 2.

Honest broker will take list and assign each patient to a clinician based on the clinician seen most frequently (over last 3 years).

-

Step 3.

The list will be stratified by clinician.

-

Step 4.

If a clinician has <15 patients, then delete clinician and clinician’s patients (revise N to be the number of patients remaining).

-

Step 5.

If, and only if, N <175, then take all patients for the practice (inclusive sample randomization not necessary).

-

Step 6.

If N ≥ 175, each clinician specific list of patients will be randomized by honest broker as follows below.

-

Step 7.

Calculate the proportion p of patients to be sampled; p = 175/N.

-

Step 8.

The number of patients on a particular clinician’s list is n. For each clinician in a practice, calculate n × p. If n × p > 15 for each clinician, then randomly sample n × p patients and sampling is complete. If n × p ≤ 15, then go to Step 9.

-

Step 9.

If n × p ≤ 15 for a particular clinician, then randomly sample 15 patients for that clinician and sample n × p patients for the other clinicians.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zimmerman, R.K., Nowalk, M.P., Terry, M.A. et al. Assessing Disparities in Adult Vaccination Using Multimodal Approaches in Primary Care Offices: Methodology. J Urban Health 85, 217–227 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-007-9247-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-007-9247-6