Abstract

A mixed-methodology approach was employed to gain a better understanding of international graduate students’ perceptions of academic and social isolation, both in traditional and online environments, to see if these differ, and to explore suggestions for improving their sense of engagement within their learning communities. A survey was completed by 54 respondents and ten individuals participated in focus group sessions or individual interviews. The results show that international students, both in traditional and online programs, experience/perceive high levels of isolation, academically and socially. However, online international students may feel even more isolated than their traditional counterparts. The independent variables gender, type of degree, and family presence appear to also have some influence on some of the respondents’ answers. Participants suggested several types of potential interventions they would find useful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United States (U.S.) continues to be the destination of first choice for many prospective international graduate students, in spite of the 2007–2008 stall in numbers of international graduate program applicants (Council of Graduate Schools 2008) and a marked increase in international competition in the recruitment of international students. In the Institute of International Education’s (IIE) November, 2007 press release Allan E. Goodman, President and CEO of the IIE, commented that:

Given increased global competition for talent, as well as expanded higher education options in many of the leading sending countries, America needs to continue its proactive steps to insure that our academic doors remain wide open, and that students around the world understand that they will be warmly welcomed. (¶ 4).

The Institute of International Education (2006) Open Doors report for the 2005/2006 academic year reported 259,717 international graduate students in the U.S., comprising 46% of all international students reported on student visas in the U.S. The Council of Graduate Schools (2008) report states that there has been a marked decline in international graduate student applications and also emphasizes the increased international competition for international students. These current reports indicate that it is in the best interest of higher education institutions to pay more attention to their current and future international graduate students.

Given the percentages of international students in graduate programs, it is clear that the growing online component of graduate education at American institutions also affects international students. Many higher education institutions offer online courses and degree programs and teach using hybrid learning environments. In the fall of 2007, the number of online students exceeded 3.9 million (Allen and Seaman 2008). The literature on international students’ struggles and experiences in American graduate programs and the literature on the online student experience both note student isolation as a major challenge in student success.

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of international graduate students’ perceptions of academic and social isolation, both in traditional and online environments, and to probe for international graduate students’ suggestions for improving their sense of engagement within their learning communities. The research questions addressed in this study included: (1) How isolated do international graduate students feel at a western research university?; (2) How isolated do online international graduate students feel?; and (3) What type of interventions do international graduate students suggest to improve their feeling of engagement in their academic and social environments? We also ran exploratory analyses to detect whether there were any differences in perceived isolation based on gender, type of degree, family presence, length of time in the U.S., and cultural origin. This study aimed to further explore international students’ perceptions of academic and social isolation in both the traditional and online learning environments and to seek possible solutions.

Literature review

International students’ struggles and perceived isolation

Several studies (Byram and Feng 2006; Kinnell 1990; Klineberg and Hull 1979; Ladd and Ruby 1999; McNamara and Harris 1997; Poyrazli and Kavanaugh 2006; Senyshyn et al. 2000; Tomich et al. 2000; Tompson and Tompson 1996; Wille and Jackson 2003) explore the challenges and hurdles experienced by international students attending institutions of higher education in the U.S. Some of these difficulties include, but are not limited to: language difficulties; difficulties adjusting to the academic culture in the U.S.; misunderstandings and complications in communication with instructors and faculty; feelings of isolation and alienation; and culture shock and issues concerning adjustment and adaptation. Mastering a language that is not one’s own is a persistent and ongoing struggle for international students. Studying in a foreign language is not only a matter of mastering day to day conversation but also gaining a lingual toe hold in the discipline’s academic terminology. Language difficulties can lead to confusion, misunderstandings, struggles with course and program content as well as contribute to great anxiety, and stress concerning in-class participation and presentations.

Along with language, international students are confronted with culture shock and the process of acculturation. This is not only a process of finding one’s way in the host country’s culture, but also navigating the differences between academic cultures and ways of thinking and seeing the world, or learning shock (Okorocha 1996). Many of the above mentioned studies and others suggest that the factors of gender, type of degree program, accompanying family members, living conditions, length of time in U.S., and cultural origin significantly affect the perceptions and experiences of international students (Park 2002, Senyshyn et al. 2000; Tomich et al. 2000). Therefore, we chose to incorporate items in the survey instrument that reflected these factors and to explore whether they indicated differences in international graduate students’ perceptions of academic and social isolation.

McClure’s (2007) study of international students’ cross-cultural adjustment identifies four themes concerning international students’ experiences: student/supervisory relationship, academic/organizational marginalization, social marginalization, and advantaging. Isolation, making up two of the major categories in this recent study, indicates a very real and relevant issue in improving the learning environment and overall success in academic and professional development for international graduate students. This study aimed to measure overall perceived isolation of international graduate students, but we also applied the concepts of academic and social isolation as a theoretical framework to further guide our investigation and interpretations. For this study we defined academic isolation as a feeling of marginalization and anxiety in adapting to new learner roles and relationships and stress concerning the ability to perform in a teaching and learning environment and ability to undertake independent research (McClure 2007). Social isolation was defined as pervasive feelings of loneliness, dissatisfaction, marginalization, and heightened levels of interpersonal distress (Reynolds and Constantine 2007) resulting in withdrawal or inability to successfully integrate into one’s social milieu (McClure 2007). By international graduate students, we mean students enrolled in graduate programs at the university whose place of origin is other than the U.S.

Graduate students’ perceived isolation

There are strong unspoken traditions and assumptions that undergird the supervision of graduate students. They are assumed to be independent, critical thinkers, and strong writers, and if they are not already so, it is assumed that they will acquire these characteristics by observing and imitating other students and their advisors (Manathunga and Goozee 2007). The supervision structure of graduate students mimics that of a cognitive apprentice relationship, and is “built up on a transmissive approach to education, where students want to be filled up with their supervisor’s knowledge” (p. 309). Further assumptions are that graduate programs choose talent instead of “growing it” and that scholars in training will be able to develop themselves into independent academics, teachers, and researchers with minimal pedagogical interference. Lee (2008) nevertheless, writes, “We know that the supervisor can make or break a PhD student” (p. 267) and Ives and Rowley (2005) state that the communication between the supervisor and student is the most important component in the development of graduate students. Ku et al. (2008) emphasize, “The mentor/mentee relationship may be even more vital for international graduate students because they are dealing with a high level of cultural adjustment and language barriers, along with attempting to understand the culture of academia” (p. 366). We also know that engagement in the learning community is crucial to the success of graduate students (Cross 1998).

Lee (2008) identifies the following key concepts in the supervision of graduate students: functional/project management, enculturation, critical thinking, emancipation, and development of a quality advising relationship. Studies (Brown 2007; McClure 2007) recognize that a more functionalist and pragmatic approach presides in the advising relationship, where both graduate students and faculty work under the pressure of their workload and other duties and responsibilities. Research on the advising relationship with international graduate students cite heightened interpersonal and acculturative distress (Reynolds and Constantine 2007), lack of supervision (McClure 2007), differences in expectations between advisor and advisee (cultural dissonance), and failure in communication (Brown 2007). These tendencies can contribute to perceived feelings of academic isolation on the part of international graduate students.

International graduate students are more reliant on advising relationships in building social networks and finding means and support for their academic and personal needs. Records indicate that the attrition rate from doctoral programs has ranged consistently over the past recent decades somewhere between 40–50% (Schinke and da Costa 2001). While it is recognized that the graduate student experience can be intensely stressful and perplexing, it can be particularly so for international students. Faculty and advisors need to be more conscious of their role in contributing to the development of international scholars’ social networks and engagement in the local community of scholars. This study explored international graduate students’ suggestions as potential interventions that might alleviate feelings and perceptions of isolation.

Online students’ perceived isolation

Some of the major concerns that pertain to online courses are course quality, student and instructor readiness, student motivation and satisfaction, and learner attrition. These factors can be interrelated and influence student retention. Attrition has been a problem with distance education. Moore and Kearsley (1996) report that the online course dropout rate was quite high—30–50%—in the past. Undergraduate- (Richards and Ridley 1997) and graduate-level online courses (Terry 2001) have both been affected by higher attrition rates than compared to residential courses. Shaw and Polovina (1999) point out that the social isolation of online students “is widely documented” (p. 22) and may be a contributing factor to high dropout rates in online courses.

Cross (1998) mentions “the isolation that exists for large numbers of commuting, part-time students” is one criticism “of the pedagogies of our time” (p. 5). Learners construct their knowledge when they are placed in active roles and in social learning environments that are safe. Learning communities are vital to the practice of scholarship. In small groups, learners can exchange ideas and make connections between existing and new knowledge, enabling them to integrate newly acquired knowledge. It is the learning communities in which we participate that help us build our experience and develop our scholarship. It is noted that this can be particularly challenging in the online and distance environment.

When students participate in scholarship online, there is a strong possibility of isolation given that many will not meet in person during a course or a program of study. The online environment offers advantages for learners such as time to think about and reflect on instructional material, the ability to carefully craft a written response to threaded discussion posts, the option of concealing one’s country of origin and second language difficulties, and so forth. On the other hand, students may experience higher levels of isolation because they have limited opportunities to participate in engaging learning communities and to receive important peer support, both cited as critical by Cross (1998) and McClure (2007). These assumptions may particularly hold true when learners are at stage in which self direction, self determination, and confidence are critical. Smith and Shwalb (2007) note that online communication may improve students’ communications and ties to their home and can improve the process of acculturation, however “extensive computer use may also be related to social isolation” (p. 168). Their results show that time spent socializing in person was more highly correlated with adjustment than communication on the computer.

The literature indicates that in person contact and graduate students’ relationships within their learning communities are key factors in their adjustment and success, no less so in the online learning environment (Hudson et al. 2006). The existing research highlights isolation as a main concern for international students, and a growing concern about the isolation of online students.

Methodology

Setting

The study took place at a western research-extensive university in the U.S. The university offers 71 academic graduate programs in seven colleges and three schools. In spring 2009, student enrollment exceeded 13,000. In spring 2008, approximately 3.5% of students were identified as international students and the total enrollment of graduate international students was 248.

Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire. Researchers invited several students to participate in two focus group sessions. Eight students were able to participate during the scheduled sessions, and two students who were not able to attend the sessions were willing to participate in individual semi-structured interviews. As an incentive focus group and interview participants received lunch and a campus bookstore gift certificate.

Data collection

Instrument

The questionnaire is comprised of 25 five-point Likert scale items, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, three open-ended questions, one multiple-response item, nine demographic questions, and one overall perception of isolation scale item represented by a 9.3 cm line ranging from not isolated at all to totally isolated (see appended instrument). The questions were intended to measure the constructs of perceived academic and social isolation. Questions were directly derived from the literature (Byram and Feng 2006; Kinnell 1990; Klineberg and Hull 1979; Ladd and Ruby 1999; McNamara and Harris 1997; Poyrazli and Kavanaugh 2006; Senyshyn et al. 2000; Tomich et al. 2000; Tompson and Tompson 1996; Wille and Jackson 2003).

The instrument was included (See “Appendix” section) twice in an electronic newsletter that is distributed to all international students. Researchers distributed the paper-based questionnaire after spring break at one international student event. Five international graduate students known to the researchers were recruited to distribute copies to other international students to utilize the snowball effect, a data collection procedure used to obtain referrals in order to identify knowledgeable individuals (Patton 2002).

Interview schedule

Focus group and interview sessions were held on campus and lasted 60-minutes. The interview schedule included questions pertaining to issues such as happiness with their current lives, difficulties they encountered when they first arrived on campus, individuals who support them, additional support needed, suggestions for improving their social and academic lives, and a question about courses primarily delivered online (see appended list of interview questions).

Data analysis

Survey data

Researchers examined the data for statistical assumptions. Three cases had missing data; these were substituted with the mean. Bivariate scatterplots were generated and examined in order to examine for linearity. Pearson correlation coefficients were examined to determine if multicollinearity existed. The six highest correlation coefficients in the matrix are between items 17 and 18 (.78), items 5 and 14 (.67), items 2 and 4 (.67), items 4 and 13 (.66), items 3 and 4 (.65), and 20 and 24 (.64). The collinearity diagnostic shows that the highest variance proportion is .85. Therefore no multicollinearity or singularity exists. Because the instrument includes items on a 5-point Likert scale, all of the scatterplots reveal abnormalities between the variables. An examination of z scores revealed two outliers within the range of z ± 3.00; these cases were deleted from the data set.

Frequencies were generated before 12 negative items were recoded. Means and standard deviations were calculated. To determine the instrument’s internal reliability the Cronbach alpha coefficient was used. Independent sample t tests were performed with three independent variables: gender, type of degree, and family presence. A one-way analysis of variance was run after participants were sorted into three groups depending on length time of study in the U.S. A correlational analysis was run after calculating the total score of Likert-scale items for each case. Chi-squares were calculated after participants were grouped into four categories (continent) based on their country of origin and eight groups (colleges and schools) depending on their programs of study. Qualitative data generated with open-ended questions were analyzed using open coding in order to categorize the data and find emerging themes (Flick 2006).

Focus group sessions and interviews

To analyze the range of answers that student interviewees provided in describing how they make sense of their experiences abroad, recordings of focus group discussions and individual interviews were transcribed and reviewed. The data were coded through a process of open coding, and emerging themes were analyzed both individually and across interviews for further analysis. Precautions in order to increase the “trustworthiness” (Lincoln and Guba 1985) of the research and to minimize threats to its credibility included conducting multiple data collection strategies and triangulation. Member checks were used to verify the accuracy of the researchers’ interpretations and representation (Bogdan and Biklen 2003; Creswell 2003; Patton 2002). Researcher journals and extensive memoing were used to exercise researcher reflexivity to identify personal subjectivities.

Results

Respondents

Fifty-four individuals who completed the questionnaire represented 24 countries. The countries that were represented the most were: (1) China (16.7%), (2) Indonesia (14.8%), and (3) Kenya (9.3%). The majority of respondents were male (55.6%), enrolled in a master’s program (51.9%), and did not have their families living with them (53.7%). Participants had studied in the U.S. between 3 and 160 months (M = 32.35). Most of the participants (87%) had a graduate assistantship, teaching assistantship, or scholarship to study at the university. Only 14 (26.9%) respondents participated in online courses.

Isolation of international students

Survey results

Thirty-six individuals responded to the scale item on which they marked how isolated they felt. The range was 6.75 with respondents marking from 0 to 6.75 on the 9.3 cm scale (M = 2.5) (Table 1). Respondents most “strongly agreed” or “agreed” with the following items: they are happy with their academic life at the university (87.1%); colleagues and instructors listen to and pay attention to their contributions in class (83.3%); their input and points of view are equally valued in their learning environment (83.3%); and their intelligence and hard work are acknowledged by their peers and advisors (83.0%).

At least 70% strongly agreed or agreed with the following items: they feel comfortable in the learning environment provided by the department (79.6%); they feel they have the academic support that they need to be successful in their studies at the university (77.7%); they have a circle of friends on whom they can rely on (74.0%); they feel comfortable working with their American colleagues (72.2%); and they feel equally respected as academics and future professionals (72.2%). Items with which individuals most disagreed or strongly disagreed are as follows: their difficulties with the English language make it hard for them to talk to faculty (77.8%) or other students (70.3%); and Americans think they are incompetent because they are quiet (72.2%). Individuals’ responses were fairly split for three items: they always feel foreign at the university; they spend most of their time with other international students; and Americans do not value their culture. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the scale was very high (a = .91).

Independent-sample t tests were performed to evaluate differences in gender, type of degree, and family presence. It was hypothesized that gender, type of degree, and family living with the student would yield statistically significant differences in response to some of the questions. The t test with the independent variable gender was significant for two items. Item 21, t(50) = 2.98, p = .004, and item 25, t(50) = 2.38, p = .02, were significant. Males had a higher mean score for both questions than females.

The type of degree (master or doctorate) sought resulted in only one significant result, question 18, t(49) = 2.04, p = .05. Doctoral students had a lower mean than master students for this item. Four items yielded significant differences in means when the family variable was evaluated. Students who had their families living with them had significantly higher means on items 6, t(49) = 2.25, p = .03; 7, t(49) = 3.60, p = .001; 20, t(49) = 2.05, p = .05; and 24, t(49) = 2.30, p = .03.

A one-way analysis of variance was conducted to evaluate the relationship between the length of time participants had been studying in the U.S. and their levels of isolation. The independent variable, length in months, included three levels: 1-12 months, 13-36 months, and 37 months or more. The ANOVA was significant for item 23, F(2, 49) = 4.65, p = .01. Follow-up tests were conducted to evaluate pairwise differences among the means. The variance among the three groups ranged from .37 to .93. Post hoc comparisons with the use of the Tukey were performed. There was a significant difference in the means in item 23 between the two groups who had studied up to 12 months and between 13 and 36 months in the U.S. The mean for the individuals who studied in the U.S. up to 12 months was higher. The 95% confidence intervals for the pairwise differences are reported in Table 2.

Chi-square tests were conducted to evaluate whether participants’ responses differed depending on the continent of their origin and college. The four continent variables were Asia, Europe, Africa, and Central America. The six colleges or schools were engineering; arts and sciences; education; business; agriculture; and environmental and natural resources. The results of the test with the continent variables were statistically significant for eight of the scale items: item 2, χ²(9, N = 52) = 61.21, p < .01; item 3, χ²(12, N = 52) = 29.26, p < .01; item 4, χ²(9, N = 52) = 31.38, p < .01; item 12, χ²(9, N = 52) = 19.05, p < .05; item 13, χ²(9, N = 52) = 26.69, p < .01; item 18, χ²(12, N = 52) = 26.31, p = .01; item 22, χ²(12, N = 52) = 22.79, p < .05; and item 24, χ²(12, N = 52) = 60.86, p < .01. Results of the test with college variables were not statistically significant.

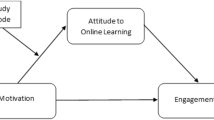

A total scale score was calculated for each participant. A correlation coefficient was computed between total scale scores and isolation scale scores. The result revealed that there was statistically significant correlation (a = −.41, p < .05) (Fig. 1).

Focus groups and in-depth interviews

Similar to the survey results, when directly asked if they felt isolated, most participants answered that they did not feel isolated at all. International graduate students have a strong sense of purpose in completing their academic programs and taking advantage of the educational and career opportunities they have been afforded, or what McClure (2007) coined advantaging. However, when asked to further describe the challenges they struggle with and how they feel about their studies here in the U.S., they often described situations of acute academic and social isolation.

Participants made a number of statements that indicated various aspects of their perceived academic isolation. One concern was the lack of familiarity with the academic culture and expectations. “We need a better idea about what research is, and what we are supposed to accomplish with our research. What is the overall perspective about research? I never did any research before.” For example, “What is the IRB, a proposal and all of that? Giving us a hint would be a great help in the long run. We would learn more and gain more from the research courses if we had this first.” Another participant corroborated this statement, “Not knowing what is expected is very tough.”

Participants also talked about feeling as though the academic experience was one-way communication. “There is this sense that we as internationals have to learn everything about U.S. culture but I don’t think that it goes both ways.” Another participant agreed, “We are learning from you, but are you learning from us and are you interested in learning from us?” Others felt as though there was little support offered to them as international graduate students.

So I think that the support of the process of acculturation is a piece that I am not seeing anywhere. And that is where the sense of isolation came. You can be surrounded by a hundred people and still feel like you are alone because no one is acknowledging how hard you are working to get by here.

Another participant confirmed this perception, “I have to agree, there is not a lot of support here… I didn’t actively seek it… you kind of have to randomly figure these things out through other people.” Similar feelings and statements indicated that the participants felt as though they were not really a part of the learning community. Another participant summarized,

I think I fit in enough that I can function without anyone noticing or not. I know enough about the culture where I don’t make these faux pas where people wonder what’s wrong with me. So I think I can function well enough, but the fit is still not there – I have different interests and perspectives.

Others felt as though their thinking was wrong, “Sometimes the international students can’t think like they should, maybe the university can help them,” while others felt as though they did not even exist, “I felt invisible.” One participant explained how “People wouldn’t return our greetings or comments in class. You feel bad because you almost always have to be the initiator, and you feel really bad when people don’t even respond.” Her friend agreed, “I would have dropped out of my first face-to-face class if the other international student hadn’t been in there with me.” Another continued, “Yeah, I felt like we don’t match, I could feel we don’t belong here.” Others felt fear and anxiety when it came to participation in the learning environment. “I often feel uncomfortable speaking up and asking questions in class.” Others agreed, “Often your accent speaks more than anything else.” Participants all reflected on moments in the classroom when they felt as though they did not belong, sensed their differences, and alternative perspectives were not recognized, were unwanted, or were simply ignored. These instances and feelings all contribute to what we have termed academic isolation (McClure 2007).

Students also described instances of social isolation, or feeling closed off from those around them. Many of the participants described long hours of study and laughed when we asked them about their social lives. Several students replied by saying that they have no social lives, or that their social lives have been sacrificed or put on hold for their academic pursuits. Perceived social isolation felt by the interviewees was reflected in statements like, “I wouldn’t use the word isolated, but… I don’t have that many friends around anymore… Recently it’s been getting worse. I don’t have many friends,” and “Yeah, I don’t really fit in anywhere.” Many expressed that they were unhappy and some even described depression. “I wouldn’t say I’m unhappy, but I am not particularly happy.”

A few participants described how they focused on the future and hopes for finding a better place to live when they were finished with graduate school. “I am hoping to graduate and go to a larger place and find some friends.” Another commented, “To be honest, we don’t have many good friends. It is hard to make friends here.” It was apparent that the participants were employing coping mechanisms to lessen their feelings of social isolation.

Other contributions to the conversation also reflected perceived social isolation. “I try to stick to academic stuff (in conversation with colleagues) because we all do the work, but not other things. I only talk to people about academic stuff––assignments, deadlines, writing papers. We don’t socialize.” Another student described the lives of acquaintances, “I know many international students who say they have only been to the student union or to the library once a semester. They just stay in the lab all of the time and do their experiments. Often they only have one day off, so they just sleep. I don’t think they socialize very much.” Another summed up her experience, “I need friends, but I don’t know how to make friends here.”

Participants also expressed that being physically distinctive from the surrounding community also made them feel hesitant to participate in social events. For example, “I feel invisible in the church. Physically distinguishable from other Americans, I feel that I am imagined to be exotic and different.” Another student explained feelings of not belonging.

The longer I have occupied a place in the U.S. and the deeper my roots here, my psychological ties are more attached to my original culture. Now I feel neither [as] insider nor outsider. I think my identity has been negotiated. I think all of my ‘negotiations’ have been derived from my language barrier… the U.S. is not my ‘place’.

Another contributed, “Here, I don’t like to go out much because I feel people look at me weird.” Other participants agreed, “Yeah, you cannot go out alone, so we just stay at home.”

Many interviewees also pointed out that there are fewer opportunities for graduate students to be involved in university life than for undergraduate students. Financial and student visa pressures contribute to many students’ need to quickly work through their programs, so they take heavier course loads, and work harder to meet requirements and finish research projects in a timely manner. They also described being physically exhausted from working through the material, reading course content several times, and staying long hours in their offices and labs, leaving them little energy for socialization. Others reported that they have their families with them, and whatever time they have left is devoted to caring for spouses and children. Several students mentioned that the spouses of international graduate students are the ones who suffer true isolation. Whatever the reasons and explanations, participants described very isolated lives lacking in opportunities for socialization outside of their academic responsibilities, and expressed deep concern for their spouses who suffered even greater isolation.

Isolation of online international students

Participants’ feelings and responses regarding their experiences in online classes as compared to their traditional face-to-face courses seemed mixed. On the one hand, the online courses offered a venue that felt “safer” in some respects. Students could work on their own time, at their own pace, and they could work on and edit their responses before posting them to the class. The online environment offered some comfort in that they were less anxious about speaking in front of groups or “finding a pause in the conversations” where they could jump in. However, students reflected concern about meeting the expectations in online courses, as they did not seem clear. Others mentioned that making the transition to an online and more progressive environment is particularly difficult for the students from more traditional university systems in their home countries. Another student mentioned that, “Online courses make it more difficult to meet the other doctoral students and to make friends.”

Several statements reflected the mixed nature in feelings toward the online environment. Some comments were very positive, “I really like online classes, but the first semester is tough,” and “The school work here seemed much easier to me. I could take more classes at one time combining my online and on-campus classes.” Other participants’ statements were much more negative, “I hate my online classes. I hate staring at the computer. I prefer to talk to people,” or “If I had a better background in technology, I would have been more successful.” One student added, “These things (complications with the technology and the course work) add to the extreme of not being in your comfort zone and no one is there to help you.” Though the feelings were mixed, it seemed like participants preferred to be with their colleagues in class, “Face-to-face classes make the program more personal.” One participant put forward, “I would suggest more face-to-face classes in the beginning to ease the transition from totally traditional to totally progressive education.” Another explained:

Having my family here I don’t think I really feel too isolated, but I know there is a distinct difference between on-campus classes and online classes in the level of involvement in just getting to know the other students. Just being there in person, there is a level of involvement that you don’t get in an online class… And I didn’t feel it was as important as my on-campus classes, because I didn’t have to show up. Even though they track the time you spend on it, it didn’t quite feel like a real class sometimes… All I had to do to avoid it was just not turn on my computer!

Another participant shared her experience:

Being an international student working on group projects with other students (in person) I felt very involved. It was very interesting and intriguing, but when I did my work off campus and just communicated via e-mail, the projects definitely seemed different. My involvement was a lot less when I was working from a distance. There was definitely a component that was missing – being on campus and being involved and all of that.

Even though many of the participants described great discomfort and acute anxiety about speaking and participating in the traditional classroom setting, most of them seemed to prefer the traditional classroom to the added isolation of working online. Even though they were afforded more time to think and prepare their statements in the online courses, in some respects, it seemed as though they were missing out on what they came abroad for—a cultural experience. One student admitted that her participation is greater in the online courses, because she does not have to worry about her accent as much, but she still preferred the traditional classroom. Also, as many of the students often mentioned, they felt like they were alone and had very little or no help in their online courses, signaling both social and academic isolation. Students seemed satisfied with the content of the online portion of their programs, but felt that the learning community aspect of online courses was missing.

Intervention suggestions

Survey responses

Participants were asked to select events, activities, and programs which they might find interesting or helpful from a list included in the survey. Most individuals who responded indicated that professional development seminars during which issues such as research, writing, funding, interviewing, etc. would be helpful. One person voiced concern about the quality of existing seminars. Thirty-five persons thought informal lunches with other graduate students and faculty would be of value. Orientations that included topics such as academic cultures, resources, and expectations of advisors and faculty were selected by 32 participants. Thirty students checked regular meetings with colleagues and faculty within their departments to discuss research. Other events included peer review sessions, panel discussions, and a buddy system.

Respondents suggested the following to improve their lives in response to the final open-ended question: (a) social events with U.S. students, (b) assistance with the English language, e.g. conversation partners, and (c) assistance with writing in English not only with grammar but also with paraphrasing and citations.

Focus groups and in-depth interviews

Participants mentioned a number of possibilities that they felt would have contributed to a more supportive environment for them throughout their graduate studies. Some suggestions included:

-

More information about expectations and differences in academic cultures.

-

A better informed, smoother transition from traditional educational settings to more progressive settings.

-

Regular contact with others in the program to talk about and share research ideas as well as more professional development.

-

Seminars or meetings to discuss: What is research?; How do we conduct it?; What does the process look like?; How do we get published?; What does a resume and curriculum vita look like in the United States?; and, How do we find jobs?

Discussion

Participants’ responses to the survey questions were relatively positive. Interestingly, at the beginning of the sessions, focus group and interview participants reported that they were happy and did not feel very isolated. As the sessions progressed, participants were less reluctant to voice higher levels of isolation in both the academic and social sense.

The independent variables gender, type of degree, and family presence influenced some of the respondents’ answers. Males had statistically significant higher mean scores for two questions. First, they felt more strongly that they had a circle of friends on whom they could rely on and they felt less overwhelmed some days. Respondents who pursued a master’s degree experienced a lower level of difficulties in talking to faculty members based on foreign language issues. Graduate students who had their families living with them compared to those who did not felt more comfortable in the learning environment provided by their departments and in approaching faculty outside of the classroom; they also worried less about problems here and felt less invisible.

There was a statistically significant difference between participants who had been studying on their degree in the U.S. between 0 and 12 and 13–36 months. Students who were in their first year of study at the institution in the U.S. felt more equally respected as an academic and future professional than students who were in their second and 3rd year, suggesting that their adjustment is a long-term process that extends beyond culture shock.

When we evaluated whether participants’ responses differed depending on the continent of their origin, we found that Asian participants were less likely to agree that their intelligence and hard work was acknowledged by their peers and advisors, that their input and points of views were equally valued in the learning environment, and they felt more invisible than students from other continents. Europeans agreed more that their input and points and view were equally valued and that they had the academic support they needed to be successful in their studies in the U.S. Additionally, they felt better about talking to faculty regardless of language difficulties and felt that Americans valued their culture. Students from Africa, however, felt more confident in their English language skills.

These results lead us to believe that many international students at this western university are in fact quite isolated, even though they may not be aware of their high levels of isolation or may employ coping strategies in order to continue their studies. Unfortunately, we were unable to ascertain differences in isolation of students who take some online courses versus their more traditional counterparts without violating major statistical assumptions. However, the data collected through focus group and individual interviews reveal that online international students may be more isolated than their counterparts in traditional learning environments. International students attend U.S. campuses mainly for advanced studies, good program quality, good academic atmospheres, and international experiences. The online environment may provide certain benefits; however, the drawbacks, at this time, outweigh its advantages and do not coincide well with international students’ reasons for studying abroad.

The following limitations should be considered when interpreting results. First, the study is geographically limited as it only includes international students at one higher education institution. Further studies should be conducted to validate the survey and focus group/interview results. Second, the sample was relatively small due to the small population of international students at the institution. Third, the land grant university is located in a small, rural town that is relatively isolated. Fourth, survey data were self-reported. Fifth, the project was funded by the College of Education with a specific reporting time frame and we did not want to contaminate our sample. Hence, no pilot for instrument validation was conducted; however, we employed triangulation through a mixed-methods approach to address this limitation.

Conclusion

Returning to Lee’s (2008) study, the four major concepts in the supervision of graduate students that were identified directly apply to providing better support for international graduate students and reducing their sense of isolation. Lee envisions a more rounded approach in supporting the personal, academic, and professional development of graduate students, one that reflects a more caring approach to the advising relationship. The common pragmatic and functionalist approaches to advising graduate students and the tensions felt are well understood under the workload faculty bear; however, it is the responsibility of both the departments and the institutions to support and cultivate the students admitted into programs. If international students are expressing such acute academic and social isolation on a day-to-day basis in their educational endeavors here in the U.S., then we should heed their requests for help and look to find ways to better support them in a more holistic sense. This project allowed the international graduate participants to speak for themselves and suggest possible programmatic responses. The data, however, produced no technical solutions. We suggest this study be repeated in other contexts and with greater sample sizes to further confirm similar trends. In terms of future development and direction, researchers may investigate solutions to learning issues and concerns in light of media attributes that did not naturally emerge from our research. These questions may include: What aspects of technology (instructional design and/or medium used) need to be monitored to reduce international students' every day challenges? What kind of online delivery system has been (or should be) used to reduce anxiety or isolation among international students? Indeed, as Maslow (1943) pointed out, if a person’s physical and emotional needs are not tended to, then he or she will not be fit for higher learning.

References

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2008, November). Staying the course: Online education in the United States, 2008. Needham, MA: Sloan Consortium. Retrieved 23rd Jan 2010, from http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/survey/pdf/staying_the_course.pdf.

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (2003). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods (4th ed.). New York: Allyn and Bacon.

Brown, L. (2007). A consideration of the challenges involved in supervising international masters students. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 31(3), 239–248.

Byram, M., & Feng, A. (Eds.). (2006). Living and studying abroad: Research and practice. Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Council of Graduate Schools. (2008). Findings from the 2008 CGS international graduate student admission survey. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved 21st July 2008, from http://www.cgsnet.org/Portals/0/pdf/R_IntlApps08_I.pdf.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cross, K. P. (1998). Why learning communities? Why now? About Campus, 3(3), 4–11. Retrieved 10th March 2008, from Academic Search Premier database.

Flick, U. (2006). An introduction to qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hudson, B., Hudson, A., & Steel, J. (2006). Orchestrating interdependence in an international online learning community. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(5), 733–748.

Institute of International Education. (2006). Open doors online: Report on international educational exchange. New York: Author. Retrieved 21st July 2008, from http://opendoors.iienetwork.org/?p=89206.

Institute of International Education. (2007). International student enrollment in U.S. rebounds. New York: Author. Retrieved 21st July 2008, from http://opendoors.iienetwork.org/?p=113743.

Ives, G., & Rowley, G. (2005). Supervisor selection or allocation and continuity of supervision: PhD students’ progress and outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 30(5), 535–555.

Kinnell, M. (Ed.). (1990). The learning experience of overseas students. Bristol, PA: Society for Research into Higher Education.

Klineberg, O., & Hull, W. F. (1979). At a foreign university: An international study of adaptation and coping. New York, NY: Praeger.

Ku, H. Y., Lahman, M. K. E., Yeh, H. T., & Cheng, Y. C. (2008). Into the academy: Preparing and mentoring international doctoral students. Educational Technology Research and Development, 56, 365–377.

Ladd, P., & Ruby, R. (1999). Learning styles and adjustment issues of international students. Journal of Education for Business, 74(6), 363–367.

Lee, A. (2008). How are doctoral students supervised? Concepts of doctoral research supervision. Studies in Higher Education, 33(3), 267–281.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Manathunga, C., & Goozee, J. (2007). Challenging the dual assumption of the ‘always/already’ autonomous student and effective supervisor. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(3), 309–322.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). The theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.

McClure, J. W. (2007). International graduates’ cross-cultural adjustment: Experiences, coping strategies, and suggested programmatic responses. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(2), 199–217.

McNamara, D., & Harris, R. (Eds.). (1997). Overseas students in higher education: Issues in teaching and learning. New York: Routledge.

Moore, M. G., & Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance education: A systems view. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Okorocha, E. (1996). The international student experience: Expectations and realities. Journal of Graduate Education, 2(3), 80–84.

Park, K. (2002). Transformative learning: Sojourners’ experiences in intercultural adjustment. Ph.D. dissertation, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, IL, USA. Retrieved 30st Dec 2007, from ProQuest Digital Dissertations.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Poyrazli, S., & Kavanaugh, P. R. (2006). Marital status, ethnicity, academic achievement, and adjustment strains: The case of graduate international students. College Student Journal, 40(4), 767–780.

Reynolds, A. L., & Constantine, M. G. (2007). Cultural adjustment difficulties and career development of international college students. Journal of Career Assessment, 15(3), 338–350.

Richards, C., & Ridley, D. (1997). Factors affecting college students’ persistence in on-line computer-managed instruction. College Student Journal, 31(4), 490. Retrieved 4th Feb 2008, from Academic Search Premier database.

Schinke, R. J., & da Costa, J. (2001). Considerations regarding graduate student persistence. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 47, 341–352.

Senyshyn, R. M., Warford, M., & Zhan, J. (2000). Issues of adjustment to higher education: International students’ perspectives. International Education, 30(1), 17–35.

Shaw, S., & Polovina, S. (1999). Practical experiences of, and lessons learnt from, Internet technologies in higher education. Educational Technology & Society, 2(3), 16–24. Retrieved 28th July 2008, from http://www.ifets.info/journals/2_3/stephen_shaw.pdf.

Smith, T. B., & Shwalb, D. A. (2007). Preliminary examination of international students’ adjustment and loneliness related to electronic communications. Psychological Reports, 100(1), 167–170.

Terry, N. (2001). Assessing enrollment and attrition rates for the online MBA. Technology Horizons in Education Journal. Retrieved 27th July 2008, from http://www.thejournal.com/articles/15251.

Tomich, P., McWhirter, J., & King, W. (2000). International student adaptation: Critical variables. International Education, 29(2), 37–46.

Tompson, H. B., & Tompson, G. H. (1996). Confronting diversity issues in the classroom with strategies to improve satisfaction and retention of international students. Journal of Education for Business, 72, 53–57.

Wille, H., & Jackson, J. (2003). Understanding the college experience for Asian international students at a midwestern research university. College Student Journal, 37(3), 379–391.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the College of Education at the University of Wyoming for its generous financial support of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

International Student Survey

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Erichsen, E.A., Bolliger, D.U. Towards understanding international graduate student isolation in traditional and online environments. Education Tech Research Dev 59, 309–326 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-010-9161-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-010-9161-6