Abstract

In this commentary, we build on Xinying Yin and Gayle Buck’s discussion by exploring the cultural practices which are integral to formative assessment, when it is viewed as a sociocultural practice. First we discuss the role of assessment and in particular oral and written formative assessments in both western and Samoan cultures, building on the account of assessment practices in the Chinese culture given by Yin and Buck. Secondly, we document the cultural practice of silence in Samoan classroom’s which has lead to the use of written formative assessment as in the Yin and Buck article. We also discuss the use of written formative assessment as a scaffold for teacher development for formative assessment. Finally, we briefly discuss both studies on formative assessment as a sociocultural practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Written formative assessment (Furtak and Ruiz-Primo 2008) was used in the study by Xinying Yin and Gayle Buck as a way to scaffold the implementation and use of formative assessment in the science classrooms of one teacher in China. In this article we add to the discussions by examining the use of written formative assessment in another non-western culture—Samoa.

Samoa is an independent South Pacific island nation situated near the equator and 2,900 km north east of New Zealand, with a population of 195, 000 in the 2006 census. In the 2006 New Zealand census, Samoans were the largest Pacific ethnic group (131,103 Samoans) in New Zealand of New Zealand’s Pacific population (265, 974 Pasifika peoples in total or 6.9 %), with the current total New Zealand population being 4,242,048 (2012 census) (New Zealand Statistics Department 2013). Samoans also live and work in Australia: 39,992 in the Australian 2006 census, (Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 2011), for example, in the cities of Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. There are also Samoans living on the west coast of the United States of America (USA). Hence, there are as many Samoans living away from Samoa as in Samoa. And Samoan children may be present in classrooms in New Zealand, Australia, and the west coast of the USA.

Yin and Buck view formative assessment as a sociocultural practice, referring to a definition of culture as: the norms, values, beliefs, expectations, emotional responses and conventional actions of a group and insiders (Phelan, Davidson and Cao 1991).

A consideration of culture is important when using a teaching and assessment approach developed using the cultural norms of one society with students of another culture. Formative assessment may be considered a sociocultural practice because it is ‘a purposeful, intentional activity involving meaning making; an integral part of teaching and learning; a situated and contextualized activity; a partnership between teacher and students; and involving the use of language to communicate meaning.’(Bell and Cowie 2001a, p. 114).

It is this last part of this quotation that is of interest here; formative assessment involves communication between teacher and student or student to student to co-construct shared meanings, which are culturally situated. Communication uses language—verbal, non-verbal for example in sign language and facial expressions. Formative assessment as communication has been researched as:

-

Planned formative assessment, for example, whole class brainstorms, a short test: eliciting student thinking, interpreting and acting, and

-

Interactive formative assessment, for example, working with students in small groups: noticing student language and actions, interpreting and, responding (Cowie and Bell 2001a).

And each of the aspects of formative assessment is influenced by the culture of teachers and students.

In learning to implement formative assessments in the classroom, teachers may be supported or scaffolded by using written formative assessment, so that the feedback and feedforward, can be written after the busyness of the lesson, and some thought given to the wording (Bell and Cowie 2001b). In addition, in the Yin and Buck study, the researchers implemented some of the written formative assessment to help the teacher learning to do it.

Written formative assessments, both planned and interactive assessment, require the teacher to find out what the students are thinking, through interpreting the students’ written language and also requires the teacher to write down feedback and feedforward. Written formative assessment can be used when students are silent in the classroom (Lee Hang 2011), when teacher talk predominates.

Silence in the classroom is a form of communication and hence a cultural practice. Silence does not communicate ‘nothing’ or ‘emptiness’. In western countries, silence of a student might communicate that the student did not hear the teacher, does not know the answer to the teacher’s question, is shy, lacking confidence or is deliberately refusing to engage with the teacher. In addition, formative assessment depends on the quality of the relationship between teacher and student. A student will tend to disclose what they know and do not know, when they feel they can trust the teacher with these disclosures (Cowie 2000). But what constitutes trust in a teacher–student relationship from both the teacher’s and student’s perspective is often based on what cultural values they bring to the relationship (Bishop, Berryman, Cavanagh, and Teddy 2009). Much of the recent literature on formative assessment comes from the English-speaking world and, as a teaching practice, tends to be based on western values. For example, giving feedback and feedforward is a part of formative assessment but how both are given can build or destroy a sense of trust in the teacher–student relationship. Whether the feedback is given in front of class peers in a whole class discussion, or whether it is given within a conversation between teacher and student, may impact of the levels of trust in the relationship. In disclosing what they do not know, for example, students do not wish to be put-down, embarrassed or shamed, especially not in front of the whole class. There are some implicit rules of politeness in giving feedback in western cultures, based on core western cultural values. For example, students understand the classroom talk pattern of T-S-T. They know it would be disobedient and rude not to answer a teacher’s question when spoken to directly.

In the Samoan culture, young people do not orally question or answer their elders in public or in front of the whole class, and to do so would be considered disrespectful (Lee Hang 2011). Whereas this practice of questioning of elders and replying to elders in public may be more acceptable in western culture, it is not practiced in some Asian cultures (Carless 2011) or Pacific cultures, for example, in Samoan schools. Instead the cultural practice is that of silence (Lee Hang 2011). A trusting teacher–student relationship would be one in which both teachers and students understand that there would be no undue pressure within the teacher–student relationship to talk (question or answer) in front of the whole class. To be invited to talk might be considered unexpected, culturally inappropriate and disrespectful to the status of the teacher as a knowledgeable elder. The Samoan cultural practice in the classroom when the teacher is talking to the whole class is to be silent as a way of communicating respect. Hence, Samoan classrooms are characterised by the teacher talking to the whole class for most of the lesson time—teacher-directed and dominated teaching is the norm. There is little oral interaction between teacher and student, and therefore making it nearly impossible to do verbal planned or interactive formative assessment (Lee Hang 2011).

To further understand the cultural practice of silence with respect to formative assessment, research (e.g. Lee Hang 2011) was informed by theorising teaching and formative assessment as a cultural practice, within the wider theorising of a sociocultural perspective (Bell 2011), meaning that to explain and make sense of the practices of assessment for formative purposes, we need to make links between mind and action, and between these elements and the sociocultural contexts in which formative assessment is done (Wertsch 1991). In other words:

-

formative assessment can only be fully understood if the social, cultural and political contexts in the classroom are taken into account

-

the practices of formative assessment reflect the values, culture of the classroom, and in particular, those of the teacher

-

formative assessment is a social practice, constructed within social and cultural norms of the classroom

-

what is assessed is what is socially and culturally valued

-

the cultural and social knowledge of the teacher and students mediate their responses to assessment

-

formative assessments are value-laden and socially constructed (Bell and Cowie 2001a, pp. 128–129).

Samoan cultural practices and formative assessment

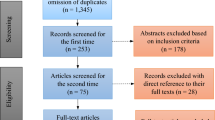

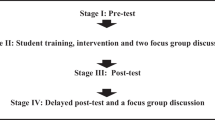

One question asked by the first author, in his role as a teacher educator of science teachers in Samoa, was whether oral formative assessment is a culturally appropriate teaching practice when undertaken in Samoan secondary schools by Samoan teachers of science (Lee Hang 2011). In the study, 16 participants were interviewed, five science teacher educators, five associate science teachers, three pre-service science teachers and three in-service science teachers. Their responses to the interview question regarding aspects of the Samoan culture that they think would affect formative assessments are quoted in this chapter.

For simplicity and consistency, the term ‘le tautala’ is used to refer to the phenomenon of pupil silence in the classroom, which is commonly displayed by those who are fully capable of speech. Although the term ‘le gagana’, which loosely translates as the silence displayed by a person without a language, could be used, it was decided to use the word le tautala because a person can use any different form of a language such as verbal (i.e. talking, singing, crying), textual (i.e. writing or texting), or non-verbal (i.e. gestures, facial expressions, body language or even sign language) to communicate effectively. Besides, just because a person has decided not to speak, does not necessarily mean, that person has no language or nothing to say.

The following are 16 specific cultural factors identified by the secondary science teachers and teacher educators (Lee Hang 2011) as important to consider when carrying out oral formative assessments in Samoan classrooms. Some are illustrated with quotations from the data—further data and the original transcripts of the quotations in Samoan may be found in Lee Hang (2011).

-

1.

Va-fealoa’i (sacred relational space)

Va-fealoa’i refers to the protocols of respect that are generally observed to maintain the va (space) between Samoan people. Albert Wendt (1996) has succinctly explained the concept of va in the following excerpt:

Va is the space between, the between-ness, not empty space, not space that separates but space that relates, that holds separate entities and things together in the Unity-that-is-All, the space giving meaning to things. The meanings change as the relationships/the contexts change (p. 18)

This space between people is occupied by a shared understanding of culture and relationships. It is governed by the values of respect, loyalty and love for familial ties and the meanings that each relationship allocates to such a space. The following quote from one of the participants highlight the importance of va-fealoa’i and its potential to assist teachers in establishing teacher–student relationships in formative assessment:

In Samoa because of our culture or way of life, we need to observe the cultural practice of va-fealoa’i between elders or parents and children. Because there is not much difference between parents role at home and that of the teachers in schools, therefore emphasis should be placed on this cultural relationship … (T12.I1.42)

Another teacher also mentioned that the sacred space with mutual respect between females and males, and brothers and sisters needs to be considered. It should be noted that the Samoan notion of brother and sister goes beyond the nuclear family, as first or second cousins of the opposite sex also qualify to be referred to as brothers and sisters. Teachers need to consider the various aspects of va-fealoa’i as illustrated in this section before and during their lessons and assessment practices.

-

2.

Faaaloalo i e matutua (respect for elders)

Faaaloalo i e matutua is perhaps the most common and well known of cultural factors underpinning le tautala and it tends to influence other cultural factors mentioned in this section. Respect for elders is a major cultural value within Faasamoa (Samoan culture) and it tends to permeate every other aspect of Samoan society where young and old interact. So in the school environment it is not surprising that this value affects the sociocultural interactions of both teachers and pupils. As one teacher points out in the following quote, it prevents pupils from answering back even if the pupil has a point to argue or even if the teacher made an error:

… well remember in our culture there is respect … respect for the elders, not answering back even though you have a point that you may want to argue with the, with the teacher for example. You don’t want to do that because of this va [cultural or sacred relationship] because of this respect for [what] the elders or the teachers say, although the teacher may be wrong. (T4.I1.74)

It may also prevent the student from asking questions of the teacher or voicing an opinion different to that of the teacher.

-

3.

Faalogo ma usita’i i le matua (have to listen to elders/teacher)

Faalogo ma usita’i is another factor that emanated from the teachers and is the extension of cultural respect for elders in the sense that it is expected of children to listen and obey their elders/parents and in the school, their teachers. This is very strong in rural villages and the following quote illustrates this:

just like what’s happening at home in the rural villages. They listen to their parents but when they come to school they listen to the teachers as they do their parents. I know that is one reason why pupils do not speak in class, too respectful to the teacher]. (T14.I1.75)

The teachers indicated that they thought this cultural factor was a factor in the lack of teacher–pupil interactions. This cultural factor is very strong in Samoa and it is nurtured and propagated through childrearing disciplinary practices as well as Christian doctrines that promote obedience to the will of God and to parents. This cultural factor is also directly linked to the Samoan value of respect for elders.

-

4.

Le taliupua (not answering back)

Le taliupua or not answering back relates to the cultural value of respect and obedience. This is demanded by parents of their children. When asked or told to do something, children are expected not to speak. This expectation of not answering back is supported by the following teacher participant’s comment:

Yeah I think because in our culture the children are taught not to answer back to the elders so in the Samoan classroom we see a lot of students not asking questions, even though if they don’t understand or don’t know (anything) of what is discussed. It’s like they don’t want to ask questions, I mean they are not used to that questioning process because of the way they have been brought up at home. (T4.I2.55)

Furthermore, the above quote highlights the disparity between the culture of the Samoan home and the culture of the western-based education promoted in Samoan schools. However despite this, the parents and Samoan society at large view the western-based, English-instructed education with prestige and social status.

-

5.

Le tautala (silence)

Le tautala meaning ‘silent’ (Allardice 1985) is used here to refer to instances where a pupil remains silent or adopts silence in the classroom. It could also mean being non-verbal (Day 1981). The following reflects some of the many forms or causes of ‘le tautala’ found in the data:

-

Matamuli (shyness)

Matamuli or shyness was also identified by teachers as a cause or form of le tautala in the classroom.

-

Leiloa le tali (don’t know the answer)

Leiloa le tali or not knowing the answer was another reason that the teachers identified as a cause or form of le tautala in the classroom. Not knowing the answer was linked to embarrassment and shyness:

I think its embarrassment coupled with not knowing the answer and perhaps shyness because it is like embarrassment. (T15.I1.73)

-

Ma or ma-gofie (shame/embarrass or easily embarrassed)

Ma, ma-gofie or embarrassment and the fear of being embarrassed were also identified by some teachers as a cause or form of le tautala in the classroom. This is illustrated well in the following excerpt:

we are easily shamed if we say something wrong (laughs) (T4.I1.80)

The above quote refers to being ma or embarrassed as a major influence in Samoan culture especially being ‘easily shamed’ when we say or even do something wrong. And this can be a major concern for pupils during formative assessments and could well explain the existence of le tautala in Samoan classrooms. However, another teacher put it succinctly down to fear of shame from making a mistake:

There is a commonly held belief among Samoans or rather a fear of saying anything that is likely to bring us shame or make us embarrassed because we might get it wrong and then other students will laugh and then that may lead to school absenteeism. (T13.I1.10-12)

This cause or form of silence was seen to be detrimental to pupils’ learning especially when pupils are afraid to make mistakes, and may even be absent from school if they have made mistakes.

-

Fa’aaloalo (respectful)

Fa’aaloalo or being respectful is an important cultural factor to consider when one contemplates the cause of students’ le tautala in the classroom. This silence is attributed to fa’aaloalo (respect) or the act of being respectful to one’s elders, as already discussed. One teacher added that pupils from rural villages seem to lack confidence when responding and their avoidance of eye contact when asked in class, is also related to cultural respect:

A lot of the students from the rural areas, they are not as confident when they answer. Sometimes they sort of look away when you ask them a question and I think a lot of it has to do with the whole … cultural respect thing. (T1.I1.28)

-

Fefe i sese (fear of mistakes)

Fefe i sese or the fear of making mistakes, which might upset both the teacher and student was seen by some of the teachers as another factor that tends to deter pupils from responding in class and thus contributes to le tautala in the classroom. As illustrated by the following quote:

Like students who can’t answer or give a comment on an issue because they think that the teacher might not be happy with their wrong answers. (T11.I1.140)

Another teacher offered the following as an explanation of pupil silence by stating the sheer numbers of students in a class (in this case, up to 58) as well as the fact that some pupils may consider it rude or have a fear of making a mistake even if some knew the answers:

I think the biggest thing with assessment is that there’s a lot of them … they’re kind of afraid when it comes to assessment, like when you ask them questions during tutorials they may know the answers but they won’t, they won’t come out and answer it because sometimes they consider it kind of rude or they don’t want to be wrong, … which I think is part of how they were assessed in the past … it’s either right or wrong so they don’t want to say anything because they don’t want to be seen as giving the wrong answer or something. (T1.I1.24)

Again, it is important to reiterate that the fear of making a mistake is a very real cultural factor that affects pupils in Samoa and has the potential to hinder any formative assessment by the teachers.

So in summary, student silence or le tautala in the Samoan classroom can mean many things in the Samoan context. It can be matamuli (shyness), or leiloa le tali (not knowing the answer), or ma po’o le magofie (embarrassed), or due to faaaloalo (respect), or fefe i sese (fear of mistakes and the consequent mockery that comes with making mistakes). Hence student silence is culturally significant and its multiple meanings ensure that it exists in many Samoan classrooms.

-

6.

Aamu/Ulagia (mocking/mockery)

Aamu or ulagia is a cultural factor that needs to be taken onboard if one is trying to understand the dynamics of pupil interactions for formative assessment in a classroom. It refers to the cultural practice of mockery of someone who has made a mistake. The extent to which this factor affects pupils varies from being slightly annoyed to being very embarrassed and shamed:

… with Samoans … we have these … (laughs) mocking attitudes. It’s like someone says something, when someone says something wrong … they don’t try to correct it. They laugh at that (pause) they laugh at that person… (R: What happens to that person?) Embarrassed (laughs) and don’t want to talk again. (T4.I1.80-84)

-

7.

Amanai’a pe’a pasi (Gain respect if do well)

Amanaia pe’a pasi refers to being recognised and respected when you do well in school. Hence, success in examinations brings respect from peers:

Well, I only know that if you do well in any assessment or do well in exams in the community will respect you, your friends will respect you also. And … you’ll have a good reputation too. (T2.I1.68)

This factor is linked to what Sinapi Moli (1993) mentioned as the ‘prestige and status’ that one gains from being successful in pursuits within a western-based education system and from mastering the English language. However, it could be argued that this is not unique to Samoa but in terms of carrying out formative assessments this factor has a ‘make or break’ effect on pupils.

-

8.

Tamali’iaga (family/personal pride)

Tamali’iaga is an important and strong cultural factor to note because in the Samoan culture, family and personal pride is the same and equally important as illustrated in the quote below:

Ok because in Samoa pride is a big thing. (T4.I2.61)

This is especially true when saving face or when one tries to avoid situations that will potentially bring shame upon her/himself as well as her/his family:

Personal pride that … because he or she asks too many questions other students will think … he or she is dumb, stupid. (T4.I2.55)

This quote in particular gives insight into a common interpretation of inquisitive pupils in class as ‘dumb’ or ‘stupid’ by her peers. With this in mind, it is therefore not surprising to find that le tautala exists in Samoan classrooms.

-

9.

Tali uma mai le vasega (collective choral response rather than individual responses)

Tali uma mai le vasega is a classroom practice that reflects the Samoan communal culture where ‘safety in numbers’ seems to be a phrase that best describes the phenomenon of choral response that is prevalent in Samoan schools. It is a practice common in primary instruction in Samoa (Pereira 2005). Pupils seem to open up verbally when they are all expected to say an answer chorally but very few of them open up when they are singled out to say an answer on their own. As the following teacher succinctly points out, the choral response reflects the cultural practice of living in extended families and socializing communally:

…what I notice is … is that we like to work in groups because we don’t want to be the one that gets singled out. Our culture seems to emphasise, well not necessarily emphasize, but just that our social interaction tends to focus on group things maybe because we live in extended families and we work as villages you know. (T1.I2.48)

The practice of choral response seems to offer each pupil, the collective protection of anonymity, in a way that overcomes their fears and reduces the possibility of embarrassment from being ‘singled out’ or being ‘put on the spotlight’. Another teacher mentioned the negative perception of pupils to working alone where they are immediately put on the spot and will be subjected to comments such as ‘wanting to be different’ or ‘being a show off’. This is illustrated in the following quote:

…sometimes if you work alone it kind of puts you on the spot (and) at the same time they see it as you trying to pe e te fia ese a? [wanting to be different?]. Other times they will say … ‘you think you are smarter, going off on your own trying to show off your knowledge’, different things like that. … if you can’t answer it I’m sure someone else in the group can answer it or you can hide behind each other’s voice I think … (T1.I2.48)

Regardless of whether an answer is correct or incorrect, the choral response by the group protects the identity of the actual pupil, who came up with the incorrect response in the first place, from ridicule.

-

10.

Fa’aaoga le Gagana Samoa (preference for the Samoan language)

Fa’aaoga le Gagana Samoa is not a new issue as other studies (Lee Hang 2002) have documented that teachers do recognise that the English language usage in examinations, curriculum documents and textbooks especially in science, all pose problems for most Samoan children—mainly because English is not their first language. The teachers in this study agreed that the language factor continues to hinder learning in the classrooms and have advocated for the use of the Samoan language. For example, a teacher raised the language issue but in combination with pride and shame. When the teacher asked whether the students in the class had understood, the students would all say ‘yes’, but the teacher found out later that most did not understand. Their ‘yes’ could well be a means to ‘save face’ and avoid being ma (embarrassed) or subjected to ridicule (ulagia), as they may not have understood the lesson or the topic well because it was in English.

-

11.

Eseesega o le fale ma le aoga (home and school differences)

Eseesega o le fale ma le aoga, or the disparity between the home and school environment, was raised by some teachers as a cultural factor to consider when doing formative assessment. One of the teachers mentioned some students hardly speak at home because of cultural reasons, and they continue this practice in class. Another teacher suggested that some pupils who are vocal at home find the school culture daunting.

It is important to note that regardless of whether the parents/guardians support or do not support what the pupils are studying in schools, the disparity between the pupils home environment and the school environment does exist. However, it should be noted that this disparity is unlikely to change. Faasamoa (Samoan culture) in the home is obviously valued. The school culture is unlikely to return to being fully based on Faasamoa (Samoan culture) as Samoan parents perceive a western-based education and the English language as somewhat superior than the indigenous ways and language because of the status and prestige that Samoans associate with success in the current western-oriented education system. The Samoan values of ‘status seeking’ and ‘competition’ (Pereira 2005) make the high stake examinations and the current western-based education system very unlikely to be replaced; and the Government of Samoa is committed to nurturing Samoa’s economy based on western-oriented economic and educational policies developed in collaboration with, and funded by, overseas aid agencies like AusAID, NZAid and international funding institutions like the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (Samoan Ministry of Education Sports and Culture Samoa 2007).

-

12.

Nu’u e sau ai (village of origin/urban or rural)

Nu’u e sau ai refers to one’s village of origin whether urban or rural. Knowledge of a pupil’s village of origin gives the teacher another clue (if not an explanation) of why such a pupil becomes le tautala in class, particularly if they come from rural village as exemplified by the following quote:

I think in Samoa we distinguish, between rural–urban students in that I think the urban students, because they are exposed to different lifestyles from the village, they become less Samoanized compared to students in the rural areas. And the students from urban areas that I’ve come across seem to be more confident and also seem to be more proactive, more vocal. (T4.I2.55)

While the above cultural practices may result in silence in the classroom, there are also other cultural practices which mitigate against students doing written work as homework.

-

13.

Tuatuagia i feau ma tiute i le fale (doing chores at home)

Tuatuagia i feau ma tiute i le fale refers to the fact that most Samoan children have a cultural role to play at home. With this role comes responsibilities that they need to fulfil on a daily basis. As described by one teacher, students have chores to fulfil at home and this has implications for teachers who set homework, which then may be used in formative assessment in the classroom:

…the students spend … most of their time doing stuff in the village because they are expected to by their parents. They do not have enough time to concentrate on their studies. … So if you give them homework when they go home, they get home and they have other obligations and other things they are expected to do. And when they come the next day and we as teachers scold them and put them on detention but we are not considering the other side of the students. That’s why they haven’t done this homework. (T10 from VF-06/WS/D2/5.50-6.40)

Because of the cultural roles pupils carry out at home they are often exhausted in school the next day or are too tired to do their homework later in the evening.

-

14.

Fanau matutua e vaaia latou tei laiti (older children look after their younger siblings)

Fanau matututa e vaaia latou tei laiti refers to the cultural practice of older children looking after or ‘tending’ their younger toddler-aged siblings, which is common in Samoa (Mageo 1998). This cultural practice can take up a lot of time for the elder children charged with the responsibility of care for their younger ones and results in less time for their studies at home. While there may be much parental support for their children to do better in school, this cultural practice may lessen their achievement.

-

15.

Tuatuagia i fa’alavelave (encumbered in family obligations)

Tuatuagia i fa’alavelave refers to unavoidable family obligations which include various ceremonies such as: births, deaths, the blessing of a new house, or new church building, or a long boat; the celebration of the completion of a tattoo and many others. The key point here is that in a collective communal culture like Samoa, if there is a major family obligatory function going on, everyone is expected to contribute whether financially, food-wise or through servitude:

Because in the Samoan culture the students most of their time they are exposed to a lot of culture-based faalavelaves [family obligation] and other things happening at home. So they will be, they have an exam or something that, the first priority goes to doing things with their family so then they might not get time to, time to study, and also if they, if they come and write the exam after for example a funeral of some relative or close family member. I don’t think they’ll be in a good mental state to, to take up the assessment. … So many times I tell my students ‘you study in the classroom’, if they can make that time for their study that’s always better, so they are more productive in the classroom, and there’s no homework they need to do at home. (T3.I1.56)

The word faalavelave itself literally means to ‘disrupt’ or encumber someone and it really does disrupt people’s normal daily routines because the collective responsibility to ‘drop everything’ and offer assistance is very strong in the faa-Samoa. Faalavelave is a norm in Samoan daily life and it is an acceptable excuse to justify employees’ or pupils’ absence from the workplace and the classroom respectively. However in the school context the above quote has alluded to another solution of overcoming this cultural factor, that is the effective use of class time to do study rather than dishing out multitudes of homework that students realistically (due to faalavelaves) do not have enough time to do at home.

The other chores that pupils at college age level are likely to carry out include: the loading and unloading of raw carved bovine carcasses, as well as the carrying of large cooked pigs, or multiple cartons of canned herrings, or boxes and sometimes pails of corned beef during reciprocal exchanges in these faalavelaves. Hence, from a teachers’ perspective this cultural factor needs to be considered when doing formative assessments because it affects pupils’ physically and mentally. This is due to the fact that when pupils or anyone for that matter, are tired and exhausted—there is nothing much a teacher can do than to let the pupil rest. Having said that, teachers need to pre-warn students about their upcoming assessment activities so that they can free themselves from their cultural obligations (if possible). But by its very nature, a faalavelave is an ‘encumbrance’ (Pratt 1862, p. 35) which means “a thing that prevents someone from moving or acting freely” (Hawker 2006, p. 299).

Cultural factors and assessment

A total of fifteen cultural factors were identified by the teachers in this study, as being significant, in science education and formative assessment. These cultural factors include: va-fealoa’i (sacred relational space), faaaloalo i e matutua (respect for elders), faalogo ma usita’i e matutua (must listen to elders including teachers), le taliupua (not answering back), various forms of le tautala (silence), aamu/ulagia (mocking or mockery), amana’ia pe’a pasi (gain respect if do well), tamali’iaga (family or personal pride), faaaoga le gagana Samoa (preference for the Samoan language), eseesega o le fale ma le aoga (home and school difference), nu’u e sau ai (village of origin), tuatuagia i feau ma tiute i le fale (doing chores at home), fanau matutua e vaaia o latou tei laiti (older children look after their younger ones), and tuatuagia i faalavelave (encumbered in family obligations). It is these norms, values, beliefs, expectations, emotional responses and conventional actions that are brought by the teachers and students into the science classroom, and which are also used by care-givers, school managers and government officers in Education (Phelan, Davidson, and Cao 1991). Hence, it has been argued that to undertake formative assessment in a culturally responsive way, teachers in Samoa may need to use written, not oral, formative assessments within the school day and not as homework (Lee Hang 2011). However, we caution here against the stereotyping of Samoan students based on this generic data. Formative assessment itself will help teachers to ascertain the ideas, values and beliefs of the Samoan students in their class, and this generic information may help the teacher make sense of their students’ communications.

The study by Yin and Buck also used written formative assessment tasks with the one Chinese chemistry teacher to help him start using formative assessment in his classroom. Both studies did not consider it appropriate to use oral formative assessment at the start of the teacher development, that is, the western cultural practice of oral formative assessment was not considered an appropriate starting activity in these two different cultures and societies. The written formative assessment did not require the teacher to give feedback and feedforward in the busyness of the lesson; it gave the teacher time to think about the feedback and feedforward before communicating it; it matched the written assessment done for summative purposes, and enabled the teacher to maintain some of the cultural positioning of respected and knowledgeable elder in the community. In other words, written formative assessment enables the core values (and identity) of the teacher involved in teacher development to remain intact for now.

In both China and Samoa, classrooms tend to be dominated by teacher-talk, transmission teaching and exam directed teaching. However, the norms, values, beliefs, expectations, emotional responses and conventional actions behind the teacher-dominated classrooms are different (Phelan, Davidson, and Cao 1991). For example, examinations have a history of over 1,000 years in China but in Samoa the history of examinations dates from colonization in the mid-nineteenth century. But in both studies, globilisation has been a catalyst for a change to use formative assessments in classrooms so as to raise achievement. However, it is not always appropriate to implement a teaching practice unchanged from one culture to another because one has to consider, not only the new teaching and assessment practices per se, but also the norms, values, beliefs, expectations, emotional responses and conventional actions of teachers and students in both the western culture in which formative assessment arose and the country which wishes to use it. Formative assessment as a sociocultural practice is embedded in the broad social contexts of schools, societies and cultures.

References

Allardice, R. W. (1985). A simplified dictionary of modern Samoan. Auckland, New Zealand: Pasifika Press.

Bell, B. (2011). Theorising teaching in secondary classrooms: Understanding our practice from a socioculutural perspective. London: Routledge.

Bell, B., & Cowie, B. (2001a). Formative assessment and science education. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Bell, B., & Cowie, B. (2001b). Teacher development and formative assessment. Waikato Journal of Education, 7, 37–50.

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Cavanagh, T., & Teddy, L. (2009). Te Kotahitanga: Addressing educational disparities facing Maori students in New Zealand. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 734–742. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.01.009.

Carless, D. (2011). From testing to productive student learning: Implementing formative assessment in Confucian-heritage settings. New York: Routledge.

Cowie, B. (2000). Formative assessment in science classrooms. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Waikato. Unpublished PhD thesis, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Day, R. R. (1981). Silence and the ESL child. TESOL Quarterly, 15(1), 35–39. doi:10.2307/3586371.

Furtak, E., & Ruiz-Primo, M. (2008). Making students’ thinking explicit in writing and discussion: An analysis of formative assessment prompts. Science Education, 92, 799–824. doi:10.1002/sce.20270.

Hawker, S. (Ed.). (2006). Compact Oxford dictionary and thesaurus (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lee Hang, D. (2002). Bilingualism in teaching, learning and assessing science in Samoan secondary schools: Policy and practice. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji.

Lee Hang, D. (2011). Fa’afatāmanu talafeagai mo lesona fa’asaienisi: O le tu’ualalo mo a’oga a faia’oga saienisi fa’aōliōli. A culturally appropriate formative assessment in science lessons: Implications for initial science teacher education. University of Waikato. Unpublished EdD thesis, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Mageo, J. M. (1998). Theorizing self in Samoa: emotions, genders and sexualities. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Ministry of Education Sports and Culture. (2007). Education for all: Mid-decade assessment report Samoa 2007. Apia, Samoa: MESC Printery.

Moli, S. (1993). Towards a relevant science education for Western Samoa: A’oa’oga tau saienisi mo Samoa i Sisifo. Unpublished MEd degree, University of Waikato, Hamilton.

New Zealand Statistics Department (2013). Downloaded from: http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census.aspx. 23 Jan 2014.

Pereira, J. A. (2005). Aspects of primary education in Samoa: Exploring student, parent and teacher perspectives. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Phelan, P., Davison, A., & Cao, H. (1991). Students’ multiple words: Negotiating the boundaries of family, peer and school cultures. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 22, 224–250. doi:10.1525/aeq.1991.22.3.05x1051k.

Pratt, G. (1862). A Samoan dictionary: English and Samoan, and Samoan and English; with a short grammar of the Samoan dialect. Retrieved August 6, 2008 from http://books.google.co.nz/books?ct=result&id=P9VIDPfc6LQC&dq=George+Pratt+1862+grammar+and+dictionary+of+Samoa&ots=M0azGqZFHh&pg=PA52&lpg=PA52&q=faalavelave#PPA1,M1.

Wendt, A. (1996). Tatauing the post-colonial body. Span, 42–43(April–October 1996), 15–29.

Wertsch, J. (1991). Voices of the mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This review essay builds on the ideas in Xinying Yin and Gayle Buck’s paper, There is another choice-An exploration of integrating formative assessment in a Chinese high school chemistry classroom through collaborative action research.

Lead Editor: A. Oliviera.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee Hang, D.M., Bell, B. Written formative assessment and silence in the classroom. Cult Stud of Sci Educ 10, 763–775 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9600-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9600-5