Abstract

Insect herbivores by necessity have to deal with a large arsenal of plant defence metabolites. The levels of defence compounds may be increased by insect damage. These induced plant responses may also affect the metabolism and performance of successive insect herbivores. As the chemical nature of induced responses is largely unknown, global metabolomic analyses are a valuable tool to gain more insight into the metabolites possibly involved in such interactions. This study analyzed the interaction between feral cabbage (Brassica oleracea) and small cabbage white caterpillars (Pieris rapae) and how previous attacks to the plant affect the caterpillar metabolism. Because plants may be induced by shoot and root herbivory, we compared shoot and root induction by treating the plants on either plant part with jasmonic acid. Extracts of the plants and the caterpillars were chemically analysed using Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography/Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (UPLCT/MS). The study revealed that the levels of three structurally related coumaroylquinic acids were elevated in plants treated on the shoot. The levels of these compounds in plants and caterpillars were highly correlated: these compounds were defined as the ‘metabolic interface’. The role of these metabolites could only be discovered using simultaneous analysis of the plant and caterpillar metabolomes. We conclude that a metabolomics approach is useful in discovering unexpected bioactive compounds involved in ecological interactions between plants and their herbivores and higher trophic levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Plants possess a wealth of structural and chemical mechanisms to defend themselves against a wide range of attackers (Bennett and Wallsgrove 1994; Hanley et al. 2007). It is estimated that plants may produce 200,000 metabolites, of which only ~10% has been identified to date (Bino et al. 2004). Many of the ‘secondary metabolites’, defined as the metabolites not required for growth, development or reproduction of the plant, have been found to have a defensive function. The secondary plant metabolism may therefore be a rich source of novel bio-active compounds, such as insecticides, fungicides and plant-derived medicines (Isman and Akhtar 2007; Rai and Mares 2003; Ulrich-Merzenich et al. 2007).

Insect herbivores closely depend on plants for their survival and they may possess physiological mechanisms to deal with such plant defensive metabolites. Specialist insect herbivores feed on a limited number of plant species and are therefore adapted to the chemical defences of their host plant species (Schoonhoven et al. 2006; Zangerl and Berenbaum 1993). These adaptations, however, do not preclude that even specialist insect herbivores show reduced growth on diets with high levels of secondary defensive compounds (Agrawal and Kurashige 2003). In some cases, adapted herbivores may sequester plant compounds for their own defence (Aliabadi et al. 2002; Müller et al. 2001; Nishida 2002; Schoonhoven et al. 2006; Zangerl and Berenbaum 1993). This may also result in lower performance of the carnivorous insects feeding on herbivores, such as parasitoid wasps (Harvey et al. 2003; Soler et al. 2005). Because such wasps usually feed exclusively on herbivore biomass, the effects of plant chemical changes on higher trophic levels likely are conveyed via chemical and/or physiological changes in the herbivore.

The types and amounts of secondary metabolites a plant contains may be genetically determined (Marak et al. 2000; van Leur et al. 2006). In addition, plant defence levels may change upon above- or belowground herbivore feeding, referred to as induced defence responses (Agrawal et al. 1999; Bezemer and van Dam 2005; Creelman and Mullet 1995; Karban and Baldwin 1997). It is thought that plants employ induced responses because it may be energetically favourable to produce defensive metabolites only when needed (Herms and Mattson 1992) and because it allows the plant to tailor its response to the specific attacker (Reymond and Farmer 1998). Therefore the plant synthesises a range of regularory plant hormones such as jasmonic (JA) and salicylic acid (SA). JA levels increase significantly in response to herbivory, whereas SA responses are mainly associated with pathogen infection (Staswick and Lehman 1999). Even though the increases in JA levels after herbivory may be transient (Schittko et al. 2000), they may result in long-lasting chemical changes in the plant, that may last from days to weeks and even years (Agrawal et al. 1999; Karban and Baldwin 1997). Moreover, many induced responses are not only localized at the damage site, but expressed in other undamaged plant parts, referred to as the systemic plant response (Choi et al. 2006; Martin and Muller 2007; Soler et al. 2005; Soler et al. 2007; van Dam et al. 2003; van Dam and Oomen 2008; van Dam and Raaijmakers 2006). As induced responses may also be present for long periods of time they may affect not only current, but also successive herbivores and herbivores feeding on plant parts that were not damaged before (Bodnaryk 1994; Broeckling et al. 2005). Induced plant responses thus may mediate interactions between herbivores that feed temporally or spatially separated on the same plant (Englishloeb et al. 1993; Viswanathan et al. 2005).

In a previous study it was shown that in feral Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) either root or shoot induction resulted in different chemical plant responses, both in amounts and types of the metabolites synthesised by the plant (van Dam et al. 2004). In this earlier study plants were treated with the aforementioned plant hormone JA, thereby mimicking the response upon attack by a chewing herbivore (Karban and Baldwin 1997). Moreover, it enables identical induction of roots and shoots, which is not possible with real herbivores (Delano-Frier et al. 2004; Galletti et al. 2006; Gols et al. 1999; Thaler 1999; van Dam and Oomen 2008). Both root and shoot JA induction resulted in the detection of significantly elevated secondary metabolite levels in extracts prepared from the shoots. However, the leaves of root induced plants were found to contain higher levels of the (potentially more toxic) aliphatic glucosinolates, whilst the leaves of shoot-induced plants contained more indole glucosinolates (van Dam et al. 2004).

Glucosinolates are the most notorious chemical defences produced by the Brassicacea (Bennett and Wallsgrove 1994; Chew 1988; Halkier and Du 1997; Mithen 2001). Plant tissue disruption by herbivory results in the release of the enzyme myrosinase, which converts glucosinolates into highly toxic products such as isothiocyanates and nitriles (Bones and Rossiter 1996; van Dam et al. 2004). The side chain structure of the glucosinolate determines which degradation products are formed upon contact with myrosinase: several such products may be toxic to generalist herbivores, and to some extent even to specialist herbivores (Agrawal and Kurashige 2003; Chew 1988). However, caterpillars of the specialist herbivore Small Cabbage White (P. rapae) have been found to possess enzymes that interfere with the glucosinolate-myrosinase reaction, thus reducing the toxicity of the formed products (Agerbirk et al. 2006; Müller et al. 2003; Wittstock et al. 2004).

The different chemical profiles produced by root and shoot-induced plants have been found to co-occur with different growth rates of caterpillars of the small cabbage white (Pieris rapae) feeding on these plants, as well as of the related species P. brassicae. It was observed that both Pieris species grow slower when fed on shoot induced B. oleracea plants compared to when fed on root induced or on control plants (van Dam and Oomen 2008). Moreover, when the larvae of the endoparasitoid wasp Cotesia glomerata fed on either caterpillar species, they were observed to develop more slowly on caterpillars that fed on shoot-induced plants (B.L. Qui and N.M. van Dam, unpublished results). These carnivorous insects feed internally on the fat bodies of the caterpillar: hence it is likely that chemical changes in the caterpillar may determine the performance of the wasp (Harvey et al. 2003).

Several studies have investigated the uptake of B. oleracea compounds by Pieris caterpillars: both caterpillar species do not take up dietary glucosinolates into their fat bodies (Müller et al. 2003). Caterpillars of P. rapae do take up pinoresinol from B. oleracea plants to excrete them from their glandular hairs: whether it is present in the fat body as well is unknown (Schroeder et al. 2006). A different study showed P. brassica caterpillars take up flavonoids (Ferreres et al. 2007). In this study however, the larvae were analysed after a period of starvation. Since this does not remove all plant material from the gut, it cannot be precluded that the analysed flavonoids were present in the remaining gut contents.

The chemical changes in the caterpillar fat bodies brought about by the earlier plant treatment with JA are crucial to understand the multitrophic interactions the plant and the caterpillar are involved in. However, a priori knowledge about the chemical identity of the metabolites involved is lacking. Therefore a study employing a global metabolomics approach may provide novel insight into this system, such that compounds hitherto unknown to be active in this interaction may be discovered (Goodacre et al. 2004). This approach has been successfully applied to study JA-induced responses in Brassicaceae: many responding metabolites were unexpectedly conjugated with malate, such that they could not have been found by targeted analyses (Kim et al. 2007; Liang et al. 2006a, b; Widarto et al. 2006). It also receives increasing interest in the field of plant–host interactions (Allwood et al. 2006, 2008; Choi et al. 2004, 2006). In both the aforementioned studies into the uptake of pinoresinol and of flavonoids by Pieris caterpillars a broad-spectrum metabolomics-type analysis was essential to discover the compounds (Ferreres et al. 2007; Schroeder et al. 2006).

To determine the metabolic differences between P. rapae caterpillars that fed on feral B. oleracea plants with different attack histories, a metabolomic analysis of the plants and the caterpillars was performed. Plants were treated with JA, either on the roots or on the shoots. After this treatment, P. rapae caterpillars fed on these plants, after which the plant leaves and caterpillar fat bodies were extracted. These extracts were analysed by Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography/Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (UPLCT/MS).

The caterpillar metabolomes were expected to differ depending on the JA treatment of their host plant. Such changes may be revealed by two patterns in the data. The plant metabolic differences between induced and control plants may lead to system-wide differences in the metabolism of the feeding caterpillars: in that case, multivariate analyses will show a considerable shift in levels of a wide range of caterpillar metabolites (i.e. the metabolic profile) when the insects are challenged by differently induced plants.

Moreover, specific plant metabolites may be incorporated intactly into the caterpillar fat bodies. The uptake of such ‘caterpillar xenobiotics’ that are equal to metabolites found in the plants, would then result in changes in the levels of these specific xenobiotics in the caterpillar metabolome. Because such incorporation does not necessarily result in changes of caterpillar metabolic pathways, this would not result in changes of entire metabolic profiles observable by multivariate data analysis.

For both patterns, specifically the metabolic differences between caterpillars feeding on shoot-induced plants and feeding on control plants are of interest: these differences may relate to the poorer caterpillar performance observed before, as well as to the effects on higher trophic levels (van Dam and Oomen 2008).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant rearing and induction

Seeds of feral Brassica oleracea were collected in a roadside population near Heteren in 2000. A sub-set of these seeds were used to grow 10 plants in the common garden at NIOO-KNAW in Heteren for seed production in 2004. Seeds from this batch were germinated on glass beads and tap water for 7 days, after which the seedlings were transplanted to 1.3L pots containing plain sand. The pots were placed on tables in a greenhouse at 21°C (day) and 16°C (night), r.h. 60% and watered and supplied with Hoagland nutrient solution as needed. Every 2–3 days, five randomly chosen pots were weighed to determine the volume of solution needed to maintain the water content in the pots at 17%. Earlier studies showed that these feral B. oleracea plants suffer from phosphorus deficiency when grown on plain sand and 0.5 Hoagland solution. Therefore we doubled the concentration of KH2PO4 in the 0.5 Hoagland solution. Natural daylight was supplemented with sodium lamps to maintain the minimum PAR at 225 μmol m−2 s−1 with a photoperiod of 16:8 (L:D).

After 29 days the plants were randomly subdivided into four treatment groups: control, root induction and shoot induction, each containing 15 plants. The fourth, blank group contained six plants. An amount of 500 μg jasmonic acid (JA; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was applied per plant, because this amount has been shown to significantly increase and differentially induce glucosinolates in B. oleracea shoots 3–14 days after induction (van Dam et al. 2004). In the ‘root induction’ group, 500 μg JA per plant was applied in 10 ml 0.1% Triton and 0.5% EtOH in water (pH = 4) by injecting the solution with a plastic syringe (without a needle) in the soil surrounding the root-shoot interface. Plants in the ‘shoot induction’ group were treated by gently rubbing 0.25 ml of a 2 mg/ml JA solution in 0.1% Triton and 0.5% EtOH (pH = 3.3) in water onto two fully expanded leaves, usually the oldest two leaves. To control for the effects of acid application, the plant organs that were not treated with JA solution and both parts of the control plants received similar amounts of 0.1% Triton and 0.5% EtOH in acidic water (pH = 3.7 with HCl) on leaves and shoots. The plants in the blank group were treated on both plants by a solution of 0.1% Triton and 0.5% EtOH in water. Immediately after JA application, each plant received extra nutrients (50 ml Hoagland solution).

2.2 Insect feeding

First instar larvae of Pieris rapae (L.) (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) were obtained from a culture maintained at the Laboratory of Entomology, Wageningen University, The Netherlands, on Brussels sprouts (B. oleracea var. gemmifera. cv. Cyrus). Three days after the plants had been induced by JA, six neonate larvae were placed on the untreated leaves of each plant. The larvae were allowed to move and feed freely on the shoot. Opaque PE sleeves open at both ends and fixed with a rubber band were placed around the pots, to prevent the larvae from migrating to other plants. The initial mass per larva was assessed by weighing 10 neonate larvae on a microbalance to the nearest 0.1 mg. On day five the larvae were counted, weighed and the three largest larvae per batch were placed on plants that received the same treatment as the first plant, also 3 days before. Thereby larvae always had access to sufficient leaf material of plants that were JA- treated between 3 and 8 days before. Final larval mass was recorded at 13 days after start of the experiment, when the first caterpillars started to pupate.

2.3 Sample preparation

After recording their masses, the caterpillars were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried, after removing their guts and haemolymph, such that only their fat bodies remained. The caterpillars that fed on the same host plant were pooled into one sample. The leaves of the plants the caterpillars were taken off were harvested and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Plant and caterpillar samples were kept at −80°C until they were lyophilized (Labconco inc., Kansas City, MO). Plant samples were homogenized using a ball mill (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany). For extraction, 49–51 mg of each homogenized plant sample was weighed in a microcentrifuge tube. Caterpillar dry masses were weighed and then homogenized in a ball mill in microcentrifuge tubes with the addition of a little purified and calcined sea sand (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ).

Prior to chemical analysis, both plant and caterpillar samples were extracted with a solution of 70% methanol in water (both of HPLC grade, Sigma Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) and 0.1% formic acid (98/100% Aristar grade, BDH-Merck, Poole, UK). This extraction buffer was selected because it had been shown experimentally to give best metabolite coverage and reproducibility of the chromatography, when compared with buffers with 70, 75 and 80% methanol. We adjusted the extraction volume for the caterpillar samples to account for their dry weight using a volume of 1 ml/25 mg sample and 2 ml of extraction buffer was added to the plant sample aliquots. Thus metabolite concentrations in the extracts represented those in the original freeze-dried samples and were therefore comparable between plants and caterpillars.

2.4 Chemical analysis

We analysed the chemical composition of the plant and the caterpillar extracts using an Acquity UPLC system hyphenated to an LCT mass spectrometer (Waters, Manchester, UK). Samples were injected onto a 2.1 × 100 mm (1.8 μm) Waters HSS T3 column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Sample and column temperatures were maintained at 4 and 35°C, respectively. The samples were eluted using a flow rate of 0.6 ml min−1 using a chromatographic gradient of two mobile phases (water in 0.1% formic acid and acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid, Table 1). The sample extraction and chromatography were developed by adapting a previously described method, but optimised for UPLC and for the simultaneous analysis of both caterpillars and plants extracts (De Vos et al. 2007).

An electrospray source was used; sample cone voltage of 30 V capillary voltage was set at −2.4 kV, the source and desolvation temperatures were 150 and 350°C, respectively, and the desolvation and nebulizer gas flow rates were 400 l h−1 and 50 l h−1, respectively. Spectra were collected in the negative ionization W mode (ES-) at a mass resolution of approximately 10,000 (full width half maximum. Data were acquired over the m/z range 100–1,000. The measurements were performed in triplicate, to account for any analytical variability. As identical procedures were employed for extraction and chemical analysis of the plant and caterpillar samples, the metabolomes of the two organisms could be compared directly.

Product ion experiments were performed on the interface metabolites using a UPLCT/Synapt High Definition Mass Spectrometry system (Waters, Manchester, UK) operated in TOF mode. The same chromatographic protocol as used in the metabolomic experiments was employed. An electrospray source was used; sample cone voltage of 20 V capillary voltage was set at −2.8 kV, the source and desolvation temperatures were 150 and 350°C, respectively, and the desolvation and nebulizer gas flow rates were 750 l h−1 and 20 l h−1, respectively. Spectra were collected in the negative ionization V mode (ES-) at a mass resolution of approximately 10,000 (full width half maximum. Data were acquired over an appropriate mass range. CID was induced by ramping the trap collision energy from 0 to 20 V and applying a transfer-collision energy of 20 V.

2.5 Data preprocessing

Following accepted data reporting standards (Goodacre et al. 2007) the raw data from the UPLCT/MS analysis were transformed to peak tables using MarkerLynx, an application manager of MassLynx v. 4.1 (Waters, Manchester, UK). We averaged the triplicate measurements of every peak identified at a unique combination of m/z and retention time in the spectra. When only one of the three replicates contained such a peak it was discarded. When the replicates contained two peaks, it was deemed likely the third peak was not measured and therefore we averaged the height of the two peaks. If a peak occurred in less than half of the samples of every treatment group, it was unlikely to be of interest (or too low in abundance to measure reliably) and therefore discarded from all samples. The peak heights in the spectra measured of the plant samples were corrected for deviations in aliquot weight from 50 mg.

2.6 Data analysis

All data analyses were performed using the Statistics Toolbox for MATLAB (v.6.1) in MATLAB R2007b (Natick, MA). To observe system-wide metabolic variation between the different plant and caterpillar extracts we fitted a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) model on their UPLCT/MS data using the princomp routine. Significant differences between the ion abundances in the caterpillar extracts corresponding to the different treatment groups were determined by Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) using the anovan routine.

To search for caterpillar xenobiotics, the ions that were measured both in the plant and in the caterpillar extracts were selected: the correlations between the abundance of each of these ions in the plant and in the caterpillar extracts were determined. The nonparametric Spearman rank correlation coefficient was calculated for this (using the corr routine), because the ion abundances are not necessarily normally distributed.

The ions for which this correlation coefficient was high were tested for differences between treatment groups. To describe the differences between the abundances in the extracts of control and shoot-induced plants, ANOVA models were fitted to the data of both groups. This was done also for the root induced plants and for the extracts of the feeding caterpillars. The data was transformed prior to fitting these models using the transformation \( y = \log \left( {x + 1} \right) \), to fulfil requirements of normality of residuals and homogeneity of variances as much as possible: these were tested using vartestn for a Levene test for homogeneity of variances and kstest for a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality of residuals. We used the boxplot routine to generate Fig. 5.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Host plant treatment does not modify caterpillar metabolic profiles

The scores of a PCA model fitted on the UPLCT/MS data of the plant extracts (Fig. 1, right) showed that JA treatment induces system-wide changes in plant metabolism: the control plants form a cluster that is separate from the root and the shoot-induced plants. Furthermore, the control (acid) treatment does not induce system-wide changes in plant metabolism, as is shown by the overlap with the blank group. The scores of the root and the shoot-induced plants only partly overlap, which reveals that JA induced both common responses as well as specific responses that depended on where the plants were induced.

(left) PCA scores of a model fitted on the UPLCT/MS data collected from the caterpillar extracts. (right) PCA scores of a model fitted on the UPLCT/MS data collected from the plant extracts. The score markers correspond to the treatment of the host plant. The percentage of explained variation for the principal components of both models is indicated on the axis labels. The model is fitted on the data collected for the root induced, shoot induced and control plant extracts (right) or on the data collected for the extracts of the caterpillars that fed on these plants (left). The scores of the blank plants (right) and their caterpillars (left) have been calculated by projecting the data collected for the blank caterpillar extracts on these PCA loadings

The PCA scores of a model fitted on the UPLCT/MS data of the caterpillar extracts did not reveal separate clusters, neither for the first two principal components (Fig. 1, left) nor for any other combination of components: the caterpillars fed on the differently treated plants did not have discernable metabolic profiles. This suggests that the metabolic system of these specialist caterpillars is buffered against differences in host plant quality. This implies that the caterpillars are able to maintain metabolic homeostasis, despite the variable chemistry of their differently treated host plants. This is further corroborated by metabolomic analyses using Gas Chromatography coupled to Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS), focusing on the base metabolism of the caterpillars (data not shown). None of the measurable caterpillar metabolites, e.g. organic acids, amino acids, sugars, differed significantly in abundance between the extracts of caterpillars that fed on differently treated host plants.

The absence of system-wide metabolic differences between the caterpillars fed on the differently treated host plants does not imply that no such differences exist in any individual caterpillar metabolite. Using the MarkerLynx processing method revealed 2,319 different ions in the caterpillar extracts. However, the ANOVA models fitted for each individual ion in the caterpillar extracts did not yield any significant differences between the differently treated host plants when corrected for the False Discovery Rate (FDR); (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Therefore also univariate analyses did not reveal metabolic differences between the caterpillars on differently treated host plants.

3.2 A ‘metabolic interface’ emerges between plants and caterpillars

Using the same Markerlynx processing method, 1,833 different ions were measured in the plant extracts. Of these ions, 753 were measured in both the plant and the caterpillar extracts. This intersect represents the subset of metabolites that may have possibly been taken up from the plant into the caterpillar and incorporated intactly into their fat bodies. They are therefore putative caterpillar xenobiotics.

However, not all xenobiotics may be of equal interest to this study. Only those plant compounds that significantly affect the caterpillar metabolome are of interest. Such effects would be indicated by high correlations between the level of an ion in the plant extracts with that in the extract of the feeding caterpillar. The subset of metabolites exhibiting such high correlations between their abundance in the plant and caterpillar are defined here as the ‘metabolic interface’ between the two organisms: the caterpillar metabolome is possibly altered by the plant metabolome via these metabolites.

A subset of seven ions had a moderate to high correlation coefficient (>0.6) between their abundance in the plant and in the caterpillar extracts (Weckwerth et al. 2004). These coefficients were exceptionally high, compared to those of the other ions measured in both the plant and the caterpillar extracts (Fig. 2): the coefficients remained significant after FDR correction on all 753 ions. The abundance of the ion of m/z 337.092 at retention time (t R) 3.41 in the caterpillar extracts clearly depends on that in the extracts of their host plant (Fig. 3, left).

Histogram showing the distribution of the Spearman rank correlation coefficient sizes between the abundance of each ions in the plant and in the caterpillars. The circles correspond to the Spearman rank correlation coefficients of the ions in Table 2

(left) Relationship between the abundance of the m/z 337 ion of the metabolite with retention time 3.41 (see Table 2) in the caterpillar extracts and in that of their host plants. Points have been marked according to the treatment of their host plant, the bars indicate the standard deviation between the replicate measurements of this ion in every sample. (right) Relationship between the abundance of the m/z 337 ion of the metabolite with retention time 3.41 in the caterpillar extracts with the ion of m/z 337 with retention time 2.55 in the caterpillars. Points have been marked according to the treatment of their host plant, the bars indicate the standard deviation between the replicate measurements of this ion in every sample

The ions with a correlation coefficient between their abundances in the plant and caterpillar extracts above the threshold level eluted at three different retention times: 2.55, 3.41 and 3.76 min, which may indicate the presence of three different metabolites, each of which detected as a series of adduct ions (indicated in Table 2 by the labels A, B and C). An ion with exact mass m/z 337.092 was the base peak at each of the retention times: it is therefore proposed that this is [M–H]− and that the three detected metabolites are isomers.

The abundances of the three different isomers were highly correlated within the caterpillar extracts. The Spearman correlation coefficients between the base peaks of metabolites A, B and C ranged from 0.944 to 0.957 (see Fig. 3 for an example). These coefficients were even larger when calculated for their abundances in the plant extracts: this indicates the synthesis of all three compounds by the plant is regulated simultaneously.

The identity of these three metabolites could be tentatively assigned as coumaroylquinic acids (CoQA, C16H18O8, Δm/z < + 0.3 mDa), based on their exact mass (http://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?cpd+C10441+-s). These compounds may be any of a range of esters between coumaric and quinic acid. This identity was further corroborated by product ion experiments performed on a UPLC/SYNAPT HDMS system (Waters, Manchester) operating in TOF mode, The product ion spectrum for the ion with m/z 337.092 of interface metabolite A in the (Fig. 4) is shown. Product ions with exact masses consistent with that of coumaric acid (m/z 163.0399, Δm/z + 0.4 mDa) and quinic acid (m/z 191.057, Δm/z + 1.4 mDa) were detected, along with several other ions that could be attributed to putative CoQA product ions with the MassFragment module of MassLynx (Waters, Manchester). Analysis of the ions with m/z 337.092 eluting at the other retention times resulted in the formation of the same fragment ions.

This subsequent analysis also showed that the ions with m/z 405.08 measured at the three retention times are adducts of the CoQAs with sodium and formic acid. The identity of the ion with m/z 535.036 is unknown: due to its low intensity only one product ion was observed of m/z 337.092. Thus it is proposed that this ion is related to the CoQA with t R 2.55. Moreover, it should be noted that the abundance of this ion was extremely low compared to that of the other ions of the CoQA with t R 2.55.

Coumaroylquinic acids belong to the phenylpropanoids, a compound class which may be involved in the induced response to exogenous attacks of many plant species (Dixon and Paiva 1995). Several CoQAs, specifically 3, 4 and 5-p-coumaroylquinic acid, have been identified in B. oleracea cultivars (Clifford 1999). To the best of our knowledge, no biological function of these compounds in the interaction between plants and caterpillars or on higher trophic levels is known. However, the CoQAs are closely related to chlorogenic acids (caffeoylquinic acids), known to act as antifeedants to P. rapae (Huang and Renwick 1995).

The abundance of each interface metabolite has the same order of magnitude in the plants and in the caterpillars. This indicates that P. rapae does not actively sequester (intact) CoQAs into its fat body. If that were the case, the abundance of these metabolites would have been considerably higher in the caterpillar extracts than in those of the plants (Müller et al. 2001). Caterpillars of the species Epirrita autumnata, which is unrelated to P. rapae, isomerise p-CoQAs and chlorogenic acids (Salminen et al. 2004). However, because we did not measure any ions with m/z 337.092 in the caterpillar extracts that were absent in the plant extracts it is unlikely that P. rapae has similar capacities. To experimentally assess whether P. rapae caterpillars are able to metabolise CoQAs, they could be fed on an artificial diet spiked with isotope-labeled CoQAs (Webb and Shelton 1988). A subsequent chemical analysis of their metabolism, analogous to that performed in the current experiment, would reveal any breakdown products as isotope patterns in the resulting data (Hood-Nowotny and Knols 2007; Webb and Shelton 1988).

3.3 Shoot induction leads to an increase in levels of the metabolic interface metabolites

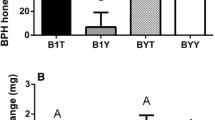

The levels of all three interface ions with m/z 337.092 are significantly higher in the shoot induced than in the control plants (Fig. 5 and Table 2), as well as in the caterpillar extracts. After root induction, only the abundance of the ion belonging to metabolite A is significantly increased in the plants compared to the control plants. However, the data of the root induced and control plants for interface metabolites A and C could not be transformed such that the homogeneity of variances criterion required for ANOVAs was fulfilled: therefore these P-values are considered with caution. No other significant differences in the levels of the interface ions with m/z 337.092 could be found between the extracts of the root induced and control plants, or of the caterpillars that fed on them.

Boxplot of the (untransformed) abundances of the ion of m/z 337 belonging to interface metabolite A (Table 2). The box ranges from the highest point within the lower quartile of the values to the lowest value in the upper quartile. The whiskers range to the adjacent values (i.e. higher and lower) than the box range. The points indicated with ‘+’ indicate the observations beyond the range of these whiskers

The concentrations of the three CoQA isomers in the plant significantly increase after shoot treatment with JA. This also leads to increased levels of these compounds in the caterpillar via the metabolic interface. Such transfer of xenobiotic compounds into the caterpillar may not only affect herbivore performance, but also that of parasitoid wasps and of higher trophic levels associated with the plant. Such compound-associated effects could be revealed by feeding the caterpillars on artificial diets spiked with different levels of CoQAs and offering them to parasitoid wasps.

The current study dealt with the effects of earlier (simulated) herbivory on the caterpillar metabolome. However, changes in plant metabolites are not exclusively triggered by biotic interactions. For example, in birch trees the levels of 5-p-coumaroylquinic acid are increased by metal pollution (Loponen et al. 2001). If B. oleracea would also respond to such perturbations by producing CoQAs, then not only ecological but also anthropogenic factors may modify caterpillar metabolism through the induced plant response.

Furthermore, the effect of CoQAs on the metabolome of other caterpillar species may be of interest. An earlier study on the growth of the generalist herbivore Mamestra brassicae that fed on JA-treated B. oleracea plants revealed that M. brassicae caterpillars performed worst on shoot-induced plants, but unlike P. rapae caterpillars also perform worse on root-induced plants than on control plants (van Dam and Oomen 2008). This indicates the CoQAs could not (fully) explain the performance differences between M. brassicae feeding on differently treated plants. The approach described in this paper could also be applied to this specific plant–insect interaction.

4 Conclusions

This study is the first in which both participating organisms in a plant–insect herbivore interaction are chemically analysed using a global metabolomic approach. Although system-wide differences in the caterpillar metabolic profiles when they feed on differently treated B. oleracea plants were lacking, the attack history of B. oleracea plants is shown to affect a specific part of the P. rapae metabolome. Extracts of plants that were shoot induced contained significantly higher levels of coumaroylquinic acids. These metabolites are shown to enter the caterpillar via the metabolic interface as it was defined here. The plant responses induced earlier by JA treatment of the plant leaves therefore metabolically affect later feeding caterpillars, although both are temporally separated.

The importance of these metabolites in the interaction between both organisms was hitherto unknown and could not have been found without a global metabolomics approach. The metabolomics approach, together with the ‘metabolic interface’ concept may form a useful tool to observe ecological interactions using metabolomics and discover hitherto unknown bioactive compounds.

References

Agerbirk, N., Müller, C., Olsen, C. E., & Chew, F. S. (2006). A common pathway for metabolism of 4-hydroxybenzylglucosinolate in Pieris and Anthocaris (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 34, 189–198. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2005.09.005.

Agrawal, A. A., & Kurashige, N. S. (2003). A role for isothiocyanates in plant resistance against the specialist herbivore Pieris rapae. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 29, 1403–1415. doi:10.1023/A:1024265420375.

Agrawal, A. A., Tuzun, S., & Bent, E. (Eds.). (1999). Induced plant defenses against pathogens and herbivores. St. Paul: APS Press.

Aliabadi, A., Renwick, J. A. A., & Whitman, D. W. (2002). Sequestration of glucosinolates by harlequin bug Murgantia histrionica. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 28, 1749–1762. doi:10.1023/A:1020505016637.

Allwood, J. W., Ellis, D. I., & Goodacre, R. (2008). Metabolomic technologies and their application to the study of plants and plant-host interactions. Physologia Plantarum, 132, 117–135.

Allwood, J. W., Ellis, D. I., Heald, J. K., Goodacre, R., & Mur, L. A. J. (2006). Metabolomic approaches reveal that phosphatidic and phosphatidyl glycerol phospholipids are major discriminatory non-polar metabolites in responses by Brachypodium distachyon to challenge by Magnaporthe grisea. The Plant Journal, 46, 351–368. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02692.x.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate—A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 57, 289–300.

Bennett, R. N., & Wallsgrove, R. M. (1994). Secondary metabolites in plant defense-mechanisms. The New Phytologist, 127, 617–633. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb02968.x.

Bezemer, T. M., & van Dam, N. M. (2005). Linking aboveground and belowground interactions via induced plant defenses. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 20, 617–624. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.08.006.

Bino, R. J., Hall, R. D., Fiehn, O., Kopka, J., Saito, K., Draper, J., et al. (2004). Potential of metabolomics as a functional genomics tool. Trends in Plant Science, 9, 418–425. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2004.07.004.

Bodnaryk, R. P. (1994). Potent effect of jasmonates on indole glucosinolates in oilseed rape and mustard. Phytochemistry, 35, 301–305. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)94752-6.

Bones, A. M., & Rossiter, J. T. (1996). The myrosinase-glucosinolate system, its organisation and biochemistry. Physiologia Plantarum, 97, 194–208. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1996.tb00497.x.

Broeckling, C. D., Huhman, D. V., Farag, M. A., Smith, J. T., May, G. D., Mendes, P., et al. (2005). Metabolic profiling of Medicago truncatula cell cultures reveals the effects of biotic and abiotic elicitors on metabolism. Journal of Experimental Botany, 56, 323–336. doi:10.1093/jxb/eri058.

Chew, F. S. (1988). Biological effects of glucosinolates. ACS Symposium Series. American Chemical Society, 380, 155–181.

Choi, Y. H., Kim, H. K., Linthorst, H. J. M., Hollander, J. G., Lefeber, A. W. M., Erkelens, C., et al. (2006). NMR metabolomics to revisit the tobacco mosaic virus infection in Nicotiana tabacum leaves. Journal of Natural Products, 69, 742–748. doi:10.1021/np050535b.

Choi, Y. H., Tapias, E. C., Kim, H. K., Lefeber, A. W. M., Erkelens, C., Verhoeven, J. T. J., et al. (2004). Metabolic discrimination of Catharanthus roseus leaves infected by phytoplasma using H-1-NMR spectroscopy and multivariate data analysis. Plant Physiology, 135, 2398–2410. doi:10.1104/pp.104.041012.

Clifford, M. N. (1999). Chlorogenic acids and other cinnamates—Nature, occurrence and dietary burden. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 79, 362–372. doi :10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(19990301)79:3<362::AID-JSFA256>3.0.CO;2-D.

Creelman, R. A., & Mullet, J. E. (1995). Jasmonic acid distribution and action in plants: Regulation during development and response to biotic and abiotic stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 92, 4114–4119. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.10.4114.

De Vos, R. C. H., Moco, S., Lommen, A., Keurentjes, J. J. B., Bino, R. J., & Hall, R. D. (2007). Untargeted large-scale plant metabolomics using liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nature Protocols, 2, 778–791. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.95.

Delano-Frier, J. P., Martinez-Gallardo, N. A., Martinez-de la Verga, O., Salas-Araiza, M. D., Barbosa-Jaramillo, E. R., Torres, A., et al. (2004). The effect of exogenous jasmonic acid on induced resistance and productivity in amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) is influenced by environmental conditions. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 30, 1001–1034. doi:10.1023/B:JOEC.0000028464.36353.bb.

Dixon, R. A., & Paiva, N. L. (1995). Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. The Plant Cell, 7, 1085–1097.

Englishloeb, G. M., Karban, R., & Hougeneitzman, D. (1993). Direct and indirect competition between spider-mites feeding on grapes. Ecological Applications, 3, 699–707. doi:10.2307/1942101.

Ferreres, F., Sousa, C., Valentao, P., Pereira, J. A., Seabra, R. M., & Andrade, P. B. (2007). Tronchuda cabbage flavonolds uptake by Pieris brassicae. Phytochemistry, 68, 361–367. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.10.020.

Galletti, S., Barillari, J., Iori, R., & Venturi, G. (2006). Glucobrassicin enhancement in woad (Isatis tinctoria) leaves by chemical and physical treatments. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 86, 1833–1838. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2571.

Gols, R., Posthumus, M. A., & Dicke, M. (1999). Jasmonic acid induces the production of gerbera volatiles that attract the biological control agent Phytoseiulus persimilis. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 93, 77–86. doi:10.1023/A:1003826309751.

Goodacre, R., Broadhurst, D., Smilde, A., Kristal, B., Baker, J., Beger, R., et al. (2007). Proposed minimum reporting standards for data analysis in metabolomics. Metabolomics, 3, 231–241. doi:10.1007/s11306-007-0081-3.

Goodacre, R., Vaidyanathan, S., Dunn, W. B., Harrigan, G. G., & Kell, D. B. (2004). Metabolomics by numbers: Acquiring and understanding global metabolite data. Trends in Biotechnology, 22, 245–252. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.03.007.

Halkier, B. A., & Du, L. C. (1997). The biosynthesis of glucosinolates. Trends in Plant Science, 2, 425–431. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(97)90026-1.

Hanley, M. E., Lamont, B. B., Fairbanks, M. M., & Rafferty, C. M. (2007). Plant structural traits and their role in anti-herbivore defence. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 8, 157–178. doi:10.1016/j.ppees.2007.01.001.

Harvey, J. A., van Dam, N. M., & Gols, R. (2003). Interactions over four trophic levels: Foodplant quality affects development of a hyperparasitoid as mediated through a herbivore and its primary parasitoid. Journal of Animal Ecology, 72, 520–531. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00722.x.

Herms, D. A., & Mattson, W. J. (1992). The dilemma of plants—to grow or defend. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 67, 283–335. doi:10.1086/417659.

Hood-Nowotny, R., & Knols, B. G. J. (2007). Stable isotope methods in biological and ecological studies of arthropods. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 124, 3–16. doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.2007.00572.x.

Huang, X. P., & Renwick, J. A. A. (1995). Chemical and experimental basis for rejection of Tropaeolum majus by Pieris rapae larvae. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 21, 1601–1617. doi:10.1007/BF02035155.

Isman, M., & Akhtar, Y. (2007). Plant natural products as a source for developing environmentally acceptable insecticides. In Insecticides design using advanced technologies (pp. 235–248) Berlin: Springer.

Karban, R., & Baldwin, I. T. (1997). Induced responses to herbivory (1st ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Kim, J. K., Bamba, T., Harada, K., Fukusaki, E., & Kobayashi, A. (2007). Time-course metabolic profiling in Arabidopsis thaliana cell cultures after salt stress treatment. Journal of Experimental Botany, 58, 415–424. doi:10.1093/jxb/erl216.

Liang, Y. S., Choi, Y. H., Kim, H. K., Linthorst, H. J. M., & Verpoorte, R. (2006a). Metabolomic analysis of methyl jasmonate treated Brassica rapa leaves by 2-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. Phytochemistry, 67, 2503–2511. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.08.018.

Liang, Y. S., Kim, H. K., Lefeber, A. W. M., Erkelens, C., Choi, Y. H., & Verpoorte, R. (2006b). Identification of phenylpropanoids in methyl jasmonate treated Brassica rapa leaves using two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Journal of Chromatography A, 1112, 148–155. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2005.11.114.

Loponen, J., Lempa, K., Ossipov, V., Kozlov, M. V., Girs, A., Hangasmaa, K., et al. (2001). Patterns in content of phenolic compounds in leaves of mountain birches along a strong pollution gradient. Chemosphere, 45, 291–301. doi:10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00545-2.

Marak, H. B., Biere, A., & Van Damme, J. M. M. (2000). Direct and correlated responses to selection on iridoid glycosides in Plantago lanceolata L. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 13, 985–996. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2000.00233.x.

Martin, N., & Muller, C. (2007). Induction of plant responses by a sequestering insect: Relationship of glucosinolate concentration and myrosinase activity. Basic and Applied Ecology, 8, 13–25. doi:10.1016/j.baae.2006.02.001.

Mithen, R. (2001). Glucosinolates—biochemistry, genetics and biological activity. Plant Growth Regulation, 34, 91–103. doi:10.1023/A:1013330819778.

Müller, C., Agerbirk, N., & Olsen, C. E. (2003). Lack of sequestration of host plant glucosinolates in Pieris rapae and P. brassicae. Chemoecology, 13, 47–54. doi:10.1007/s000490300005.

Müller, C., Agerbirk, N., Olsen, C. E., Boeve, J. L., Schaffner, U., & Brakefield, P. M. (2001). Sequestration of host plant glucosinolates in the defensive hemolymph of the sawfly Athalia rosae. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 27, 2505–2516. doi:10.1023/A:1013631616141.

Nishida, R. (2002). Sequestration of defensive substances from plants by Lepidoptera. Annual Review of Entomology, 47, 57–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145121.

Rai, M., & Mares, D. (Eds.). (2003). Plant-derived antimycotics. Binghamton, NY: The Haworth Press, Inc.

Reymond, P., & Farmer, E. E. (1998). Jasmonate and salicylate as global signals for defense gene expression. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 1, 404–411. doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(98)80264-1.

Salminen, J. P., Lahtinen, M., Lempa, K., Kapari, L., Haukioja, E., & Pihlaja, K. (2004). Metabolic modifications of birch leaf phenolics by an herbivorous insect: Detoxification of flavonoid aglycones via glycosylation. Zeitschrift Fur Naturforschung C-a Journal of Biosciences, 59, 437–444.

Schittko, U., Preston, C. A., & Baldwin, I. T. (2000). Eating the evidence? Manduca sexta larvae cannot disrupt specific jasmonate induction in Nicotiana attenuata by rapid consumption. Planta, 210, 343–346. doi:10.1007/PL00008143.

Schoonhoven, L. M., Van Loon, J. J. A., & Dicke, M. (2006). Insect-plant biology (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Schroeder, F. C., del Campo, M. L., Grant, J. B., Weibel, D. B., Smedley, S. R., Bolton, K. L., et al. (2006). Pinoresinol: A lignol of plant origin serving for defense in a caterpillar. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103, 15497–15501. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605921103.

Soler, R., Bezemer, T. M., Van der Putten, W. H., Vet, L. E. M., & Harvey, J. A. (2005). Root herbivore effects on above-ground herbivore, parasitoid and hyperparasitoid performance via changes in plant quality. Journal of Animal Ecology, 74, 1121–1130. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.01006.x.

Soler, R., Harvey, J. A., Kamp, A. F. D., Vet, L. E. M., Van der Putten, W. H., Van Dam, N. M., et al. (2007) Root herbivores influence the behaviour of an aboveground parasitoid through changes in plant-volatile signals. Oikos, 116, 367–376.

Staswick, P. E., & Lehman, C. C. (1999). Jasmonic acid-signaled responses in plants. In A. A. Agrawal, S. Tuzun & E. Bent (Eds.), Induced plant defenses against pathogens and herbivores. St. Paul: APS Press.

Thaler, J. S. (1999). Induced resistance in agricultural crops: Effects of jasmonic acid on herbivory and yield in tomato plants. Environmental Entomology, 28, 30–37.

Ulrich-Merzenich, G., Zeitler, H., Jobst, D., Panek, D., Vetter, H., & Wagner, H. (2007). Application of the “-Omic-” technologies in phytomedicine. Phytomedicine, 14, 70–82. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2006.11.011.

van Dam, N. M., Harvey, J. A., Wackers, F. L., Bezemer, T. M., van der Putten, W. H., & Vet, L. E. M. (2003). Interactions between aboveground and belowground induced responses against phytophages. Basic and Applied Ecology, 4, 63–77. doi:10.1078/1439-1791-00133.

van Dam, N. M., & Oomen, M. W. A. T. (2008). Root and shoot jasmonic acid applications differentially affect leaf chemistry and herbivore growth. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 3, 91–98.

van Dam, N. M., & Raaijmakers, C. E. (2006). Local and systemic induced responses to cabbage root fly larvae (Delia radicum) in Brassica nigra and B. oleracea. Chemoecology, 16, 17–24. doi:10.1007/s00049-005-0323-7.

van Dam, N. M., Witjes, L., & Svatos, A. (2004). Interactions between aboveground and belowground induction of glucosinolates in two wild Brassica species. The New Phytologist, 161, 801–810. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.00984.x.

van Leur, H., Raaijmakers, C. E., & van Dam, N. M. (2006). A heritable glucosinolate polymorphism within natural populations of Barbarea vulgaris. Phytochemistry, 67, 1214–1223. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.04.021.

Viswanathan, D. V., Narwani, A. J. T., & Thaler, J. S. (2005). Specificity in induced plant responses shapes patterns of herbivore occurrence on Solanum dulcamara. Ecology, 86, 886–896. doi:10.1890/04-0313.

Webb, S. E., & Shelton, A. M. (1988). Laboratory rearing of the imported cabbageworm. New York’s Food and Life Sciences Bulletin, (122), 1–6.

Weckwerth, W., Loureiro, M. E., Wenzel, K., & Fiehn, O. (2004). Differential metabolic networks unravel the effects of silent plant phenotypes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101, 7809–7814. doi:10.1073/pnas.0303415101.

Widarto, H. T., Van der Meijden, E., Lefeber, A. W. M., Erkelens, C., Kim, H. K., Choi, Y. H., et al. (2006). Metabolomic differentiation of Brassica rapa following herbivory by different insect instars using two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 32, 2417–2428. doi:10.1007/s10886-006-9152-6.

Wittstock, U., Agerbirk, N., Stauber, E. J., Olsen, C. E., Hippler, M., Mitchell-Olds, T., et al. (2004). Successful herbivore attack due to metabolic diversion of a plant chemical defense. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101, 4859–4864. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308007101.

Zangerl, A. R., & Berenbaum, M. R. (1993). Plant chemistry, insect adaptations to plant chemistry, and host plant utilization patterns. Ecology, 74, 47–54. doi:10.2307/1939500.

Acknowledgments

NMD was supported by VIDI grant, no. 864-02-001, of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), JJJ received a grant from NIOO-KNAW, JWA and RG were supported by the EU project META-PHOR (Food-CT-2006-03622). The authors thank Tom Tytgat (NIOO-KNAW) and Yun Xu (Manchester Interdisciplinary Biocentre) for discussions and Ric de Vos (PRI, Wageningen, the Netherlands) for database searching. Warwick B. Dunn (Manchester centre for Integrative Systems Biology, Manchester Interdisciplinary Biocentre) performed the GC/MS analyses. The laboratory of Entomology of Wageningen University provided P. rapae eggs. This research was supported by VIDI grant, no. 864-02-001, of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) to Nicole van Dam, a grant from NIOO-KNAW for Jeroen Jansen and support from the EU project META-PHOR (Food-CT-2006-03622) to J. William Allwood and Royston Goodacre.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jansen, J.J., Allwood, J.W., Marsden-Edwards, E. et al. Metabolomic analysis of the interaction between plants and herbivores. Metabolomics 5, 150–161 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-008-0124-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-008-0124-4