Abstract

The U.S. and the U.K. are considered as successful models of social enterprise. The Korean government benchmarked these two models in the hope of achieving similar success, without much avail. The growth of social enterprises in South Korea is attributed to the country’s characteristically strong central government and its creation of relevant institutions and provision of support services. However, this paper provides an alternate explanation by highlighting role of the third sector as the ‘policy entrepreneur’ in agenda-setting and policy implementation with regards to social enterprises in South Korea. Additionally, the decentralized local governments as well as the market structure dominated by big businesses are also examined as the main contributors to ‘policy windows’ for the third sector’s policy entrepreneurship. The paper showcases successful development of social enterprise despite the absence of a welfare state or a well-developed third sector, and argues that the phenomenon should hold numerous policy implications for other Asian countries.

Résumé

Les États-Unis et le Royaume-Uni sont considérés comme des modèles réussis de l’entreprise sociale. Le gouvernement coréen a comparé ces deux modèles dans l’espoir de parvenir à ces mêmes résultats, sans grand succès. La croissance des entreprises sociales en Corée du Sud est liée au gouvernement central fort caractéristique du pays, ainsi qu’à sa création d’institutions adaptées et de services de soutien. Toutefois, cet article apporte une autre explication en soulignant le rôle du tiers secteur en tant qu’ « entrepreneur politique » pour établir les programmes d’action et mettre en œuvre les politiques concernant les entreprises sociales en Corée du Sud. En outre, les collectivités locales décentralisées ainsi que la structure du marché dominée par les grandes entreprises sont également étudiées comme les principaux contributeurs des « fenêtres politiques » pour l’esprit d’entreprise du tiers secteur. L’article présente la réussite du développement de l’entreprise sociale en dépit de l’absence d’un État providence ou d’un secteur tertiaire bien développé, et affirme que le phénomène devrait avoir de nombreuses incidences sur les politiques des autres pays d’Asie.

Zusammenfassung

Die USA und Großbritannien gelten als erfolgreiche Modelle des sozialen Unternehmertums. Die koreanische Regierung setzte diese beiden Modelle als Maßstab in der Hoffnung, einen ähnlichen Erfolg zu erzielen, allerdings vergeblich. Die Zunahme von Sozialunternehmen in Südkorea ist auf die charakteristisch starke zentrale Regierung des Landes sowie auf seine Gründung maßgeblicher Einrichtungen und die Bereitstellung von Unterstützungsdienstleistungen zurückzuführen. Allerdings bietet dieser Beitrag eine alternative Erklärung, indem die Rolle des Dritten Sektors als „politischer Unternehmer“bei der Festlegung von Agenden und der Politikumsetzung mit Hinblick auf soziale Unternehmen in Südkorea herausgestellt wird. Darüber hinaus werden die dezentralisierten Lokalregierungen sowie die von großen Unternehmen beherrschte Marktstruktur als Hauptbeitragende zu „Politikfenstern“für das politische Unternehmertum des Dritten Sektors untersucht. Der Beitrag präsentiert die erfolgreiche Entwicklung des sozialen Unternehmertums trotz eines fehlenden Sozialstaats oder eines gut entwickelten Dritten Sektors und legt dar, dass das Phänomen zahlreiche politische Implikationen für andere asiatische Länder haben dürfte.

Resumen

Los Estados Unidos y el Reino Unido son considerados como modelos exitosos de empresa social. El gobierno coreano utilizó como referencia estos dos modelos con la esperanza de lograr un éxito similar, sin mucho aprovechamiento. El crecimiento de las empresas sociales en Corea del Sur se atribuye al gobierno central del país, característicamente fuerte, y a su creación de instituciones relevantes y la provisión de servicios de apoyo. Sin embargo, el presente documento proporciona una explicación alternativa destacando el papel del sector terciario como el “emprendedor político” en el establecimiento de la agenda y en la implementación de la política con respecto a las empresas sociales en Corea del Sur. Asimismo, los gobiernos locales descentralizados, así como también la estructura de mercado dominada por grandes empresas también son examinados como los principales contribuyentes a “ventanas de oportunidad” para el emprendimiento político del sector terciario. El documento muestra el exitoso desarrollo de la empresa social a pesar de la ausencia de un estado del bienestar o de un sector terciario bien desarrollado, y argumenta que el fenómeno debe tener numerosas implicaciones políticas para otros países asiáticos.

摘要:美国和英国被认为是社会企业的成功典范。为实现类似成功,韩国政府以这两种模式为基准,却并未取得太多效用。一般认为,韩国社会企业的发展归因于该国典型的强大中央政府及其相关机构的创立以及支持服务的供给。然而,通过强调在韩国关于社会企业的议程设定与政策执行过程中第三部门作为“政策企业家”的角色,本文做出了另一种解释。此外,本文还对被分权的地方政府以及由大企业主导的市场结构(第三部门政策型创业的“政策窗口”的主要贡献者)进行了探究。本文展示了,尽管在没有福利或发达的第三部门(的情况)下,社会企业仍能成功发展,并认为这种现象应该对其他亚洲国家具有众多的政策启示。

ملخص: تعتبر الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية والمملكة المتحدة البريطانية كنماذج ناجحة للمشاريع الإجتماعية. هذين النموذجين مثل معايير قياسية للحكومة الكورية أملا˝ في تحقيق نجاح مماثل، دون الكثير من الفائدة. نمو المؤسسات الاجتماعية في كوريا الجنوبية يرجع إلى حكومة مركزية قوية مميزة وإنشائها من المؤسسات ذات الصلة وتقديم خدمات الدعم. مع ذلك، يقدم هذا البحث تفسير بديل من خلال تسليط الضوء على دور القطاع الثالث بإسم “منظم السياسة” في وضع جدول الأعمال وتنفيذ السياسات فيما يتعلق بالمؤسسات الإجتماعية في كوريا الجنوبية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يتم فحص أيضا الحكومات المحلية اللامركزية، فضلا˝ عن هيكل السوق الذي يهيمن عليه الشركات الكبيرة مثل المساهم الرئيسي في “دفع مقترحات السياسة “لريادة أعمال سياسة القطاع الثالث. يعرض البحث التطوير الناجح للمشاريع الإجتماعية على الرغم من عدم وجود دولة الرفاهية أو قطاع ثالث متطور، ويجادل أن هذه الظاهرة يجب أن تعقد العديد من الآثار المترتبة على سياسات البلدان الأسيوية الأخرى.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

South Korea was a typical developing country during 1960 s and 1970 s. During the time, providing welfare services or solving unemployment was not within the political realm. After democratization in the early 1990 s, providing welfare service and solving unemployment became politicized as they were assigned in their entirety to the government.

And as of July 2000, approximately 29 enterprises had been operating as cooperative (Lee, 2001).

A dollar is equivalent to approximately 1,077.5 won in Korean money.

Source: the homepage of the Department of Social Enterprise under the Ministry of Labor (http://www.socialenterprise.or.kr/ (Korean), (accessed 08/12/2008).

Interview with the CEO Lee of Hamkke Ilhaneun Seasang, 19/03/2011.

Seminar organized by a civil association, 19/03/2011; discussion forum organized by the third sector on the policies of social enterprise, 22/09/2011.

An organization that wants to be a social enterprise should take the form of an organization prescribed by the Presidential Decree, such as a corporation or an association under the Civil Law, a company under the Commercial Act or a non-profit private organization, etc.

The fourth type was added in 2011.

A nonprofit organization is exempted of corporate tax (Corporate Tax Act, Article 2).

The Special Tax Treatment Control Act, Article 85-6.

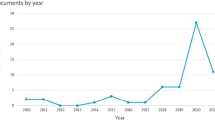

The Ministry of Employment and Labor reports the number of social enterprise quarterly, but details information of fresh social enterprise (e.g., accredited type, region and the number of employee) every year or two years.

For more on this data see the homepage of the Korea Social Enterprise Promotion Agency: http://www.socialenterprise.or.kr/ (Korean) (accessed 03/12/2011) and the homepage of the Small and Medium Business Administration: http://www.smba.go.kr/(Korean)(accessed 03/12/2011).

The social job programs was operated under the Ministry of Employment and Labor and the OUMC.

A candidate social enterprise is not an accredited social enterprise by the Ministry of Employment and Labor, but it is as a local social enterprise in the local ordinance. It is called “Local-type social enterprise” e.g., Seoul-type social enterprise, Busan-type social enterprise. Ultimately, the goal of these organizations is to become accredited social enterprise by the Ministry of Employment and Labor.

It has now turned into a city with a population of more than one million with a budget exceeding $1.85 billion.

References

Aiken, M. (2006). 16 Towards market or state? Tensions and opportunities in the evolutionary path of three UK social enterprises. Social enterprise: At the crossroads of market, public policies and civil society (p. 259).

Aiken, M., & Spear, R. (2005). Work integration social enterprises in the United Kingdom (No. 05/01). EMES Working Papers.

Auteri, M. (2003). The entrepreneurial establishment of a nonprofit organization. Public Organization Review, 3(2), 171–189.

Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (1991). Agenda dynamics and policy subsystems. The Journal of Politics, 53(04), 1044–1074.

Bornstein, D. (2007). How to change the world: Social entrepreneurs and the power of new ideas. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

Borzaga, C., & Defourny, J. (Eds.). (2001). The emergence of social enterprise (Vol. 4). Psychology Press.

Campbell, S. (1998). Social entrepreneurship: how to develop new social-purpose business ventures. Health Care Strategic Management, 16(5), 17.

Christopher et al. (2008). Compumentor and the DiscounTech.org Service: Creating an Earned-Income Venture for a nonprofit Organization. Yale school of Management, Yale Case 08-013 January 15, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2008 from http://pse.som.yale.edu/casestudies.html.

Cobb, R. W. (1983). Participation in American politics: The dynamics of agenda-building. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Dees, J. G. (1998). Enterprising nonprofits. Harvard Business Review, 76, 54–69.

Defourny, J. (2001). From third sector to social enterprise. London: The Emergence of Social Enterprise.

Defourny, J. & Nyssens, M. (2009). Conceptions of Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship in Europe and the United State: Convergences and Divergences. In Paper Presented at the Second EMES International Conference on Social Enterprise. University of Toronto, Italy. July 1–4 2009.

Eum, H. S. (2008). Social Economy in South Korea and Social Enterprise: Lessons from Europe and a Comparison (in Korean). The Institute for Policy Research Report #2. Work Together Foundation.

Evers, A., & Laville, J. L. (2004). 1. Defining the third sector in Europe. The third sector in Europe, 11.

GoRK (Government of Republic of Korea). (2007). Social Enterprise Promotion Act, 2007 (in Korean), Seoul.

Jang, W. B. (2006). Theory and Practice of Social Economy (in Korean). Seoul: Nanumuijip.

Jeong, S. (2004). Social Enterprise: successful social enterprises in the U.S. (in Korean). Seoul: Overcoming Unemployment Movement Committee.

Jones, B. D., Baumgartner, F. R., & Talbert, J. C. (1993). The Destruction of Issue Monopolies in Congress. American Political Science Review, 87(03), 657–671.

Kerlin, J. A. (2006). Social enterprise in the United States and Europe: Understanding and learning from the differences. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 17(3), 246–262.

Kingdon, J. W., & Thurber, J. A. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (Vol. 45). Boston: Little, Brown.

Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. (1999). Health and Welfare Vision 2010: Realization of Productive Welfare Community (in Korean).

Kwon, H. J. (2001). Globalization, unemployment and policy responses in korea repositioning the state? Global Social Policy, 1(2), 213–234.

Lee, H. S. (2001). A comparison of producer’s cooperatives in Korea (in Korean). Korean Journal of Sociology, 35(4), 95–127.

Lee, E. S. (2009). A comparative analysis of the characteristics of social enterprises in the United Kingdom, United States, and South Korea: An institutional approach (in Korean). Korean Journal of Public Administration, 47(4), 363–397.

McManus, P. (2004). Definition of the Social Economy in Northern Ireland-finding a way through. Social Economy Agency.

Mintrom, M. (1997). Policy entrepreneurs and the diffusion of innovation. American Journal of Political Science, 945, 738–770.

Mintrom, M., & Vergari, S. (1996). Advocacy coalitions, policy entrepreneurs, and policy change. Policy Studies Journal, 24(3), 420–434.

Nyssens, M., & Kerlin, J. (2009). Social enterprises in Europe. Social Enterprise: a Global Perspective. Lebanon: University Press of New England.

OECD. (1999). Social Enterprises, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Pearce, J., & Kay, A. (2003). Social enterprise in anytown. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Presidential Committee on Social Inclusion. (1999). The way of productive welfare to New Millennium (in Korean).

Salamon, L. M., & Sokolowski, S. W. (2006). Employment in America’s charities: A profile. National Bulletin, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies.

Sheingate, A. D. (2006). Structure and opportunity: Committee jurisdiction and issue attention in Congress. American Journal of Political Science, 50(4), 844–859.

Social Enterprise London. (2004). Social Enterprise London Business Plan 2004 ~ 2006. Retrieved November 20, 2008 from http://www.sel.org.uk.

Son, N. S. (2005). A Study on the Effectiveness Evaluation of the Self-Support Program in the National Basic Livelihood Security: Focusing on the Self-Support Program of Self-reliance aid centers in Daegu Metropolitan City (in Korean). Korean Association of Governmental Studies, 17(3), 729–759.

Suk, H. W. (2008). A Comparative Study on Work integration role of NGO and Social Enterprise (in Korean). Seoul: Seoul National University.

The Ministry of Employment and Labor. (2010). Social Enterprise Directory 501 (in Korean).

The Ministry of Employment and Labor. (2011). Internal Data (in Korean).

The Ministry of Strategy and Finance. (2011). Social Enterprise, now competitiveness is important (in Korean), Press release (21/10/2011).

Yonhap News. (Producer). (2009). Won-soon Park, Executive Directors of The Hope institute, (in Korean) [Video] http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/local/0899000000.html?cid=MYH20090106007300355&from=search.

Young, D. (2003). New trends in the US non-profit sector: Towards market integration. Paris: The Non-Profit Sector in a Changing Economy, OECD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, E.S. Social Enterprise, Policy Entrepreneurs, and the Third Sector: The Case of South Korea. Voluntas 26, 1084–1099 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9584-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9584-0