Abstract

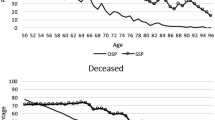

On average, “young” people underestimate whereas “old” people overestimate their chances to survive into the future. Such subjective survival beliefs violate the rational expectations paradigm and are also not in line with models of rational Bayesian learning. In order to explain these empirical patterns in a parsimonious manner, we assume that self-reported beliefs express likelihood insensitivity and can, therefore, be modeled as non-additive beliefs. In a next step we introduce a closed form model of Bayesian learning for non-additive beliefs which combines rational learning with psychological attitudes in the interpretation of information. Our model gives a remarkable fit to average subjective survival beliefs reported in the Health and Retirement Study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Our findings confirm results documented in a vast literature on subjective survival probabilities, see below.

For women we do not observe such a clear convergent pattern even for this age group.

That is, the prior and the posterior are conjugate distributions because both belong to the Beta distribution family.

Tonks (1983) introduces a similar model of rational Bayesian learning in which the agent has a normally distributed prior over the mean of a normal distribution and receives normally distributed information.

Besides the formal description of insensitivity to changes in likelihood (Wakker 2004), properties of non-additive beliefs are used in the literature for formal definitions of, e.g., ambiguity and uncertainty attitudes (Schmeidler 1989; Epstein 1999; Ghirardato and Marinacci 2002), as well as pessimism and optimism (Eichberger and Kelsey 1999; Wakker 2001; Chateauneuf et al. 2007). See Wakker (2010) for a textbook treatment.

Sensitivity analysis with respect to this assumption is presented in the online appendix.

Results are available upon request.

A qualitative difference is that inverse u-shaped experience translates into inverse u-shaped likelihood sensitivity.

We owe this interpretation to an anonymous referee.

In particular, it is not the purpose of this paper to analyze how updating of beliefs differs across particular idiosyncratic health shocks or other events that are regarded as relevant for survival belief formation in the literature, such as parental death. As we further discuss in our concluding remarks in Sect. 5, a more in depth analysis of survival belief formation based on idiosyncratic events using our framework is left for future research.

Observe that this weighting scheme implies that our point estimates are identical to a regression based on average survival rates of each group. Parameter estimates from an un-weighted regression are similar and are available upon request.

The value of the two-sided \(t\) test on the difference between the \(R^{2}\)s for men and women is 108.96 with a \(p\) value of 0.0. The values of Jarque-Bera test statistics for normality of the distribution of the bootstrapped \(R^{2}\)s (and their \(p\) values) are at 0.02 (0.99) for men and at 4.49 (0.10) for women so that a standard \(t\) test is applicable.

The \(t\) statistic of the two-sided \(t\) test for equality of the point estimates is \(3.53\).

In this argument, we can ignore for age 80 households the difference between the additive objective measure \(\pi \) and the additive subjective measure \( \tilde{b}\) because the bias factor \(\frac{2\phi ^{m-j}+h}{2+h}\) is close to one for that amount of experience.

An alternative interpretation is that focal point answers reflect ambiguity, cf. Hill et al. (2004).

As Mike Hurd pointed out to us, the first selection effect was particularly severe for the early waves of the HRS because people were not followed into nursing homes in the past. Since we use the more recent waves of the HRS where people are in fact followed into nursing homes, selection effects may only play a role for the very old respondents in our sample, if at all.

References

Baron, J. (2008). Thinking and deciding. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bleichrodt, H., & Eeckhoudt, L. (2006). Survival risks, intertemporal consumption, and insurance: The case of distorted probabilities. Insurance Mathematics and Economics, 38, 335–346.

Breiman, D., LeCam, L., & Schwartz, L. (1964). Consistent estimates and zero-one sets. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 35, 157–161.

Bruine de Bruin, W., Fischhoff, B., & Halpern-Felsher, S. (2000). Expressing epistemic uncertainty: It’s a fifty-fifty chance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 81, 115–131.

Chateauneuf, A., Eichberger, J., & Grant, S. (2007). Choice under uncertainty with the best and worst in mind: Neo-additive capacities. Journal of Economic Theory, 127, 538–567.

Doob, J. L. (1949). Application of the theory of martingales. Le Calcul des Probabilités et ses Applications, Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 13, 23–27.

Eichberger, J., Grant, S., & Kelsey, D. (2007). Updating choquet beliefs. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 43(7–8), 888–899.

Eichberger, J., Grant, S., & Kelsey, D. (2010). Comparing three ways to update choquet beliefs. Economics Letters, 107(2), 91–94.

Eichberger, J., & Kelsey, D. (1999). {E-}Capacities and the Ellsberg Paradox. Theory and Decision, 46, 107–140.

Ellsberg, D. (1961). Risk, ambiguity and the savage axioms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 75, 643–669.

Epstein, L. G. (1999). A definition of uncertainty aversion. Review of Economic Studies, 66, 579–608.

Gan, L., Hurd, M., & McFadden, D. (2005). Individual subjective survival curves. In D. Wise (Ed.), Analyses in the economics of aging. Cambridge: NBER Books, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ghirardato, P., & Marinacci, M. (2002). Ambiguity made precise: A comparative foundation. Journal of Economic Theory, 102, 251–289.

Gilboa, I. (1987). Expected utility with purely subjective non-additive probabilities. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 16, 65–88.

Gilboa, I., & Schmeidler, D. (1993). Updating ambiguous beliefs. Journal of Economic Theory, 59, 33–49.

Hammermesh, D. S. (1985). Expectations, life expectancy, and economic behavior. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 100(2), 389–408.

Hill, D., Perry, M., & Willis R. (2004). Estimating Knightian Uncertainty from Survival Probability Questions on the HRS. Presented at labor and social interaction in economics, A conference in honor of Yoram Weiss’ sixty-fifth birthday, The Eitan Berglas School of Economics, Tel-Aviv University, December 16–17.

Human Mortality Database (2008).

Hurd, M. D., McFadden, D., & Merrill, A. (2001). Predictors of mortality among the elderly. In D. Wise (Ed.), Themes in the economics of aging. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hurd, M. D., & McGarry, K. (1995). Evaluation of the subjective probabilities of survival in the health and retirement study. Journal of Human Resources, 30(0), S268–S292.

Hurd, M. D., & McGarry, K. (2002). The predictive validity of subjective probabilities of survival. Economic Journal, 112, 966–985.

Hurd, M. D., Rohwedder, S., & Winter, J. (2005). Subjective Probabilities of Survival: An International Comparison. Presented at CeMMAP workshop on Novel measurement methods for understanding economic behaviour, IFS, London, 3 July, 2008.

Kastenbaum, R. (2000). The psychology of death. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Khwaja, A., Sloan, F., & Chung, S. (2007). The relationship between individual expectations and behaviors: Evidence on mortality expectations and smoking decisions. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 35(2), 179–201.

Lee, R. D., & Carter, L. (1992). Modeling and forecasting U.S. mortality. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 87(419), 659–671.

Lijoi, A., Pruenster, I., & Walker, S. O. (2004). Extending Doob’s consistency theorem to nonparametric densities. Bernoulli, 10, 651–663.

Manski, C. F. (2004). Measuring expectations. Econometrica, 72(5), 1329–1376.

McFadden, D. L., Bemmaor, A. C., Francis, G. C., Dominitz, J., Byung-Hill, J., Lewbel, A., et al. (2005). Statistical analysis of choice experiments and surveys. Marketing Letters, 16(3–4), 183–196.

Pires, C. P. (2002). A rule for updating ambiguous beliefs. Theory and Decision, 53, 137–152.

Sarin, R., & Wakker, P. P. (1998). Revealed likelihood and knightian uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 16, 223–250.

Schmeidler, D. (1986). Integral representation without additivity. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 97, 255–261.

Schmeidler, D. (1989). Subjective probability and expected utility without additivity. Econometrica, 57, 571–587.

Siniscalchi, M. (2011). Dynamic Choice under Ambiguity. Theoretical Economics, 6, 379–421.

Smith, V. K., Taylor, D. H., & Sloan, F. A. (2001). Longevity expectations and death: Can people predict their own demise? American Economic Review, 91(4), 1126–1134.

Smith, V. K., Taylor, D. H., Sloan, F. A., Johnson, F. R., & Desvouges, W. H. (2001). Do Smokers Respond to Health Shocks? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(4), 675–687.

Steffen, B. (2009). Formation and Updating of Subjective Life Expectancy. MEA Studies 08, MEA, LMU Munich.

Tonks, I. (1983). Bayesian Learning and the Optimal Investment Decision of the Firm. The Economic Journal, 93, 87–98.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in Prospect Theory: Cumulative Representations of Uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 297–323.

Viscusi, W. K. (1985). A Bayesian Perspective on Biases in Risk Perception. Economics Letters, 17, 59–62.

Viscusi, W. K. (1990). Do smokers underestimate risks? Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1253–1269.

Viscusi, W. K. (1991). Age variations in risk perceptions and smoking decisions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 73(4), 577–588.

Viscusi, W. K., & O’Connor, C. J. (1984). Adaptive responses to chemical labeling: Are workers Bayesian decision makers? Amercian Economic Review, 74, 942–956.

Wakker, P. (2001). Testing and characterizing properties of nonadditive measures through violations of the sure-thing principle. Econometrica, 69, 1039–1059.

Wakker, P. (2004). On the composition of risk preference and belief. Psychological Review, 111, 236–241.

Wakker, P. P. (2010). Prospect theory: For risk and ambiguity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wu, G., & Gonzalez, R. (1996). Curvature of the probability weighting function. Management Science, 42(12), 1676–1690.

Zimper, A. (2009). Half empty, half full and why we can agree to disagree forever. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 71, 283–299.

Zimper, A., & Ludwig, A. (2009). On attitude polarization under Bayesian learning with non-additive beliefs. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 39, 181–212.

Acknowledgments

We thank Axel Börsch-Supan, Andrew Caplin, Alain Chateauneuf, Itzhak Gilboa, Mike Hurd, David Levine, Jürgen Maurer, Dan McFadden, Klaus Ritzberger, Susan Rohwedder, Aylit Romm, Martin Salm, Frank Sloan, Carsten Trenkler, Peter Wakker, David Weir, Joachim Winter, and an anonymous referee as well as several seminar participants at the Workshop on Subjective Probabilities and Expectations, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, 2007, at Universität Mannheim and the 2009 SAET Conference for helpful comments; and Frank Schilbach for his excellent research assistance. Financial support by the Social Security Administration (SSA) under the 2007 Steven H. Sandell Grant Program is gratefully acknowledged. Alex Ludwig further gratefully acknowledges financial support from the German National Research Foundation (DFG) through SFB 504, the State of Baden-Württemberg and the German Insurers Association (GDV). Alex Zimper is grateful for financial support from Economic Research Southern Africa (ERSA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ludwig, A., Zimper, A. A parsimonious model of subjective life expectancy. Theory Decis 75, 519–541 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-013-9355-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-013-9355-6

Keywords

- Representative agent

- Subjective survival expectations

- Likelihood insensitivity

- Choquet decision theory

- Bayesian learning