Abstract

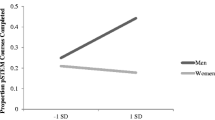

The present research examined whether gender–science stereotypes were associated with science identification and, in turn, science career aspirations among women and men undergraduate science majors. More than 1,700 students enrolled in introductory science courses completed measures of gender–science stereotypes (implicit associations and endorsement of male superiority in science), science identification, and science career aspirations. Results were consistent with theoretically based predictions. Among women, stronger gender–science stereotypes were associated with weaker science identification and, in turn, weaker science career aspirations. By contrast, among men stronger gender–science stereotypes were associated with stronger science identification and, in turn, stronger science career aspirations, particularly among men who were highly gender identified. These two sets of modest but significant findings can accumulate over large populations and across critical time points within a leaky pipeline to meaningfully contribute to gender disparities in STEM domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abelson, R. P. (1985). A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological Bulletin, 97, 129–133. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.97.1.129.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachment as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (2010). Sex differences in math-intensive fields. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(5), 275–279. doi:10.1177/0963721410383241.

Ceci, S. J., Williams, W. M., & Barnett, S. M. (2009). Women’s underrepresentation in science: Sociocultural and biological considerations. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 218–261. doi:10.1037/a0014412.

Cheryan, S., Davies, P. G., Plaut, V. C., & Steele, C. M. (2009). Ambient belonging: How stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1045–1060. doi:10.1037/a0016239.

Correll, S. J. (2004). Constraints into preferences: Gender, status, and emerging career aspirations. American Sociological Review, 69(1), 93–113. doi:10.1177/000312240406900106.

Davies, P. G., Spencer, S. J., Quinn, D. M., & Gerhardstein, R. (2002). Consuming images: How television commercials that elicit stereotype threat can restrain women academically and professionally. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1615–1628. doi:10.1177/014616702237644.

Ferriman, K., Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2009). Work preferences, life values, and personal views of top math/science graduate students and the profoundly gifted: Developmental changes and gender differences during emerging adulthood and parenthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(3), 517–532. doi:10.1037/a0016030.

Forbes, C. E., & Schmader, T. (2010). Retraining attitudes and stereotypes to affect motivation and cognitive capacity under stereotype threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 740–754. doi:10.1037/a0020971.

Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., Rudman, L. A., Farnham, S. D., Nosek, B. A., & Mellott, D. S. (2002). A unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept. Psychological Review, 109, 3–25. doi:10.1037//0033-295X.109.1.3.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1464–1480. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464.

Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197.

Halpern, D. F., Benbow, C. P., Geary, D. C., Gur, R. C., Shibley Hyde, J., & Gernsbacher, M. A. (2007). The science of sex differences in science and mathematics. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 8(1), 1–51. doi:10.1111/j.1529-1006.2007.00032.x.

Hyde, J. S., Lindberg, S. M., Linn, M. C., Ellis, A. B., & Williams, C. C. (2008). Gender similarities characterize math performance. Science, 321(5888), 494–495. doi:10.1126/science.1160364.

Inzlicht, M., & Schmader, T. (2012). Stereotype threat: Theory, process, and application. New York, NY: Oxford Press.

Kiefer, A. K., & Sekaquaptewa, D. (2007). Implicit stereotypes, gender identification, and math-related outcomes: A prospective study of female college students. Psychological Science, 18(1), 13–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01841.x.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. New York, NY: Harper Row.

Lindberg, S. M., Hyde, J. S., Petersen, J. L., & Linn, M. C. (2010). New trends in gender and mathematics performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 1123–1135. doi:10.1037/a0021276.

Lubinski, D. & Benbow, C. P. (2006). Study of mathematically precocious youth after 35 years: Uncovering antecedents for the development of math-science expertise. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(4), 316–345. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00019.x.

Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 302–318. doi:10.1177/0146167292183006.

MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., & Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1(4), 173–181. doi:10.1023/A:1026595011371.

McArdle, E. (2008). The freedom to say ‘no’. Retrieved from http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2008/05/18/the_freedom_to_say_no/?page=1.

Nosek, B. A., Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2002). Math \(=\) male, me \(=\) female, therefore math \(\ne \) me. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), 44–59. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.83.1.44.

Nosek, B. A., & Smyth, F. L. (2011). Implicit social cognitions predict sex differences in math engagement and achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 48(5), 1125–1156. doi:10.3102/0002831211410683.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. doi:10.3758/BF03206553.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. doi:10.1080/00273170701341316.

Prentice, D. A., & Miller, D. T. (1992). When small effects are impressive. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 160–164. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.160.

Schmader, T. (2002). Gender identification moderates stereotype threat effects on women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 194–201. doi:10.1006/jesp.2001.1500.

Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Barquissau, M. (2004). The costs of accepting gender differences: The role of stereotype endorsement in women’s experience in the math domain. Sex Roles, 50, 835–850. doi:10.1023/B:SERS.0000029101.74557.a0.

Shih, M., Pittinsky, T. L., & Ambady, N. (1999). Stereotype susceptibility: Identity salience and shifts in quantitative performance. Psychological Science, 10, 80–83. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00111.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. doi:10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422.

Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 34, 379–440.

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613.

Stout, J. G., Dasgupta, N., Hunsinger, M., & McManus, M. A. (2011). STEMing the tide: Using ingroup experts to inoculate women’s self-concept in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,. doi:10.1037/a0021385.

Vescio, T. K., Gervais, S. J., Heidenreich, S., & Snyder, M. (2006). The effects of prejudice level and social influence strategy on powerful people’s responding to racial out-group members. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 435–450. doi:10.1002/ejsp.344.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2003). Stereotype lift. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 456–467. doi:10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00019-2.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2007). A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 82–96. doi:10.1037/0022.3514.92.1.82.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF-HRD #1036731) awarded to Eric Loken and Theresa K. Vescio.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cundiff, J.L., Vescio, T.K., Loken, E. et al. Do gender–science stereotypes predict science identification and science career aspirations among undergraduate science majors?. Soc Psychol Educ 16, 541–554 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-013-9232-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-013-9232-8