Abstract

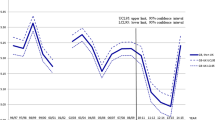

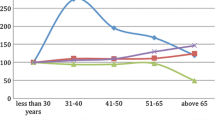

This paper uses a semiparametric latent variable transformation model for multiple outcomes to examine the effect of education and maternal education on female multidimensional well-being and proposes a procedure to build a well-being index that is less susceptible to functional form misspecification. We model multidimensional well-being as an unobserved common factor underlying the observed well-being outcomes. The semiparametric methodology allows us to alleviate misspecification bias by combining multiple indicators into a latent construct in an unspecified, data-driven way. Using data from female participants of the 1974–2010 waves of the US General Social Survey, we find that education, intelligence, and maternal education contribute positively to multidimensional well-being. However, the effects of education and maternal education on female multidimensional well-being declined steadily between the mid-1970s and the 1990s, and have not rebounded since.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The joint normal framework usually links the measureable outcomes to the latent variable using a probit function, whereas GLLAMM typically employs a log or logit link.

Better-educated mothers have higher ability, which could be transmitted to their children. Therefore, children’s schooling attainment is likely to be the outcome of this ability transmission.

These estimating equations are based on the marginal probability of \(Y_{ij} \le y_{j}\). Please see Lin et al. (2013) for details.

See Stiglitz et al. (2009), p. 14. Apart from the dimensions considered here, Stiglitz et al. (2009) suggest that well-being also depends on natural environment, security, and political voice. We ignore these macro aspects of well-being since they are largely determined by country- and regional-level factors and are less likely to be affected by individual-level characteristics such as education and maternal education.

We choose not to control for paternal education primarily to alleviate the selection problem. Another reason is that dropping observations with missing values for paternal education reduces the sample size by 20 %.

Our analyses were based on women, because we fail to achieve convergence for the male sample. It is a limitation of this study that the effects of education on male well-being cannot be analyzed, but it is a direction for future research using different data sets.

Wolfle (1980) finds that the correlation between Army General Classification Test (AGCT)—a measure of general intelligence—and WORDSUM is 0.71, confirming that verbal skills are a good measure of general intelligence.

Cor et al. (2012) document that between 1975 and 2011, WORDSUM is used in more than 100 social science studies.

The WORDSUM test—the test that provides us with a measure of general intelligence—was administered to 14,552 women in the GSS sample. After dropping cases with missing values for the other variables used, we are left with 4,634 observations.

As our model considers both discrete and continuous outcome measures, conventional goodness-of-fit measures such as \(\chi^{2}\) statistic, root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and comparative fit index (CFI), which are based on the discrepancy between the sample variance–covariance matrix and the variance–covariance matrix implied by the model with the coefficient estimates, are not applicable. As such, we assess the model fit graphically.

Blanchflower and Oswald (1999) show that approximately 51 % of the respondents answered ‘very satisfied’ to the job satisfaction question in the 1970s. By the 1990 s, that percentage fell to 46. Using the GSS data, Blanchflower and Oswald (2004) establish that from the period from 1972 to 1976 to the period from 1994 to 1998, the percentage of females reporting being very happy with their life fell from 36 to 29.

Zack et al. (2004) note that self-rated health worsened from 1993 to 2001. Using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), Salomon et al. (2009) show that Americans were increasingly likely to report ‘‘fair’’ or ‘‘poor’’ health over the period from 1993 to 2007. Zheng et al. (2011) establish that mean self-rated health in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) increased from 1984 to 1990, declined through the mid-1990 s, improved afterward, and worsened again from the late 1990 s through 2007.

The standardized factor loading is calculated by multiplying the unstandardized factor loading by the ratio of the standard deviation of the fitted value of well-being to the standard deviation of the fitted value of the transformed observed outcome.

The standardized coefficient is calculated by multiplying the estimated coefficient by the ratio of the standard deviation of the covariate to the standard deviation of the dependent variable.

According to the coefficient estimates in Table 4, the response of well-being in units of standard deviation for a one standard deviation change in education for a person with 12 years of education in the 2000s is calculated as \({{\left[ {1.1868 + 2 \times ( - 0.0207) \times 12 - 0.2688} \right] \times 2.587} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left[ {1.1868 + 2 \times ( - 0.0207) \times 12 - 0.2688} \right] \times 2.587} {1.7797}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {1.7797}} = 0.6122,\) where 1.7797 is the standard deviation of the fitted value of well-being. The well-being change for a person with 16 years of education is calculated analogously.

Given that the standard deviation for the fitted value of well-being is 1.7797, based on the coefficient estimates in Table 4, the response of well-being in units of standard deviation for a unit change in the dummy variable indicating whether the respondent was not living with both parents at age 16 is calculated as \({{0.5437 \times 0.434} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{0.5437 \times 0.434} {1.7797}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {1.7797}} = 0.1326.\)

References

Anand, P., & van Hees, M. (2006). Capabilities and achievement. Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 268–284.

Appels, A., Bosma, H., Grabauskas, V., Gostautas, A., & Sturmans, F. (1996). Self-rated health and mortality in a Lithunian and a Dutch population. Social Science and Medicine, 28, 681–690.

Arminger, G., & Küsters, U. (1988). Latent trait models with indicators of mixed measurement level. In R. Langeheine & J. Rost (Eds.), Latent trait and latent class models (pp. 51–73). New York: Plenum.

Ashenfelter, O., & Krueger, A. (1994). Estimates of the economic return to schooling from a new sample of twins. American Economic Review, 84, 1157–1173.

Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81, S279–S288.

Becker, G., & Mulligan, C. (1997). The endogenous determination of time preference. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 729–758.

Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1976). Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 84, S143–S162.

Blanchflower, D. G. & Oswald, A. J. (1999). Job security and the decline in American job satisfaction. Working paper at Dartmouth College.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Brännlund, A., Hammarström, A., & Strandh, M. (2013). Education and health-behaviour among men and women in Sweden: A 27-year prospective cohort study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 41, 284–292.

Braveman, P., Egerter, S., & Williams, D. R. (2011). The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 381–398.

Buehn, A., & Farzanegan, M. R. (2012). Smuggling around the world: Evidence from a structural equation model. Applied Economics, 44, 3047–3064.

Buehn, A., & Farzanegan, M. R. (2013). Hold your breath: A new index of air pollution. Energy Economics, 37, 104–113.

Caplan, B., & Miller, S. C. (2010). Intelligence makes people think like economists: Evidence from the General Social Survey. Intelligence, 38, 636–647.

Card, D. (2001). Estimating the return to schooling: Progress on some persistent econometric problems. Econometrica, 69, 1127–1160.

Carneiro, P., Meghir, C., & Pare, M. (2013). Maternal education, home environments, and the development of children and adolescents. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(s1), 123–160.

Catalano, P. J., & Ryan, L. M. (1992). Bivariate latent variable models for clustered discrete and continuous outcomes. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 87(419), 651–658.

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38, 179–193.

Cor, M. K., Haertel, E., Krosnick, J. A., & Malhotra, N. (2012). Improving ability measurement in surveys by following the principles of IRT: The WORDSUM vocabulary test in the General Social Survey. Social Science Research, 41, 1003–1016.

Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 294–304.

Di Tommaso, M. L. (2007). Children capabilities: A structural equation model for India. Journal of Socio-Economics, 36, 436–450.

Di Tommaso, M. L., Raiser, M., & Weeks, M. (2007). Home grown or imported? initial conditions, external anchors and the determinants of institutional reform in the transition economies. Economic Journal, 117, 858–881.

Di Tommaso, M. L., Shima, I., Strøm, S., & Bettio, F. (2009). As bad as it gets: Well-being deprivation of sexually exploited trafficked women. European Journal of Political Economy, 25, 143–162.

Diener, E., Suh, E., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Eccles, J. S., Vida, M. N., & Barber, B. (2004). The relation of early adolescents’ college plans and both academic ability and task-value beliefs to subsequent college enrollment. Journal of Early Adolescence, 24, 63–77.

Fryers, T., Melzer, D., & Jenkins, R. (2003). Social inequalities and the common mental disorders: A systematic review of the evidence. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38, 229–237.

Geoffroy, M.-C., Séguin, J., Lacourse, E., Boivin, M., Tremblay, R., & Côté, S. (2012). Parental characteristics associated with childcare use during the first 4 years of life: Results from a representative cohort of Québec families. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 103, 76–80.

Grossman, M. (2006). Education and nonmarket outcomes. In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 1, pp. 577–633). NY: Elsevier.

Gueorguieva, R., & Agrestia, A. (2001). A correlated probit model for joint modeling of clustered binary and continuous responses. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 96(455), 1102–1112.

Guerra, N., & Huesmann, L. R. (2004). A cognitive-ecological model of aggression. Revue Internationale de PsychologieSociale, 17, 177–203.

Herdt, G., & Kertzner, R. (2006). I do, but I can’t: The impact of marriage denial on the mental health and sexual citizenship of lesbians and gay men in the United States. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 3, 33–49.

Huber, P., Ronchetti, E., & Victoria-Feser, M.-P. (2004). Estimation of generalized linear latent variable models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 66, 893–908.

Kaplan, G. A., & Camacho, T. (1983). Perceived health and mortality: A nine-year follow-up of the human population laboratory cohort. American Journal of Epidemiology, 117, 292–304.

Kingston, P. W., Hubbard, R., Lapp, B., Schroeder, P., & Wilson, J. (2003). Why education matters. Sociology of Education, 76, 53–70.

Knudsen, E., Heckman, J., Cameron, J., & Shonkoff, J. (2006). Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 10155–10162. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600888103.

Kohn, M., & Slomczynski, K. M. (1993). Social structure and selfdirection: A comparative analysis of the United States and Poland. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Krishnakumar, J. (2007). Going beyond functionings to capabilities: An econometric model to explain and estimate capabilities. Journal of Human Development, 8, 39–63.

Krishnakumar, J., & Ballon, P. (2008). Estimating basic capabilities: A structural equation model applied to Bolivia. World Development, 36, 992–1010.

Latham, K., & Peek, C. W. (2013). Self-rated health and morbidity onset among late midlife U.S. adults. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 68, 107–116.

Lin, H., Zhou, L., Elashoff, R. M., & Yi, L. (2013). Semiparametric latent variable transformation models for multiple mixed outcomes. Statistica Sinica, 24, 833–854.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1998). Education, personal control, lifestyle and health: A human capital hypothesis. Research on Aging, 20, 415–449.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (2003). Education, social Status, and health. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Mistry, R. S., Vandewater, E. A., Huston, A. C., & McLoyd, V. C. (2002). Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development, 73, 935–951.

Moore, G. (1990). Structural determinants of men’s and women’s personal networks. American Sociological Review, 55, 726–735.

Mossey, J. M., & Shapiro, E. (1982). Self-rated health: A predictor of mortality among the elderly. American Journal of Public Health, 72, 800–808.

Moustaki, I. (2000). A latent trait and a latent class model for mixed observed variables. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 49, 313–334.

Moustaki, I., & Knott, M. (2000). Generalized latent trait models. Psychometrika, 65, 391–411.

Muthén, B. (1984). A general structural equation model with dichotomous, ordered categorical, and continuous latent variable indicators. Psychometrika, 49, 115–132.

Navarro, C., & Ayala, L. (2008). Multidimensional housing deprivation indices with application to Spain. Applied Economics, 40, 597–611.

Navarro, C., Ayala, L., & Labeaga, J. M. (2010). Housing deprivation and health status: Evidence from Spain. Empirical Economics, 38, 555–582.

Oreopoulos, P., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Priceless: The nonpecuniary benefits of schooling. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25, 159–184.

Park, A. L., Fuhrer, R., & Quesnel-Vallée, A. (2013). Parents’ education and the risk of major depression in early adulthood. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48, 1829–1839.

Psacharopoulos, G., & Patrinos, H. A. (2004). Returns to investment in education: A further update. Education Economics, 12, 111–134.

Ross, C. E., & Mirowsky, J. (2006). Sex differences in the effect of education on depression: Resource multiplication or resource substitution? Social Science and Medicine, 63, 1400–1413.

Salomon, J. A., Nordhagen, S., Oza, S., & Murray, C. J. L. (2009). Are Americans feeling less healthy? The puzzle of trends in self-rated health. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170, 343–351.

Sammel, M. D., Ryan, L. M., & Legler, J. M. (1997). Latent variable models for mixed discrete and continuous outcomes. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 59, 667–678.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shonkoff, J., & Phillips, D. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academic Press.

Skrondal, A., & Rabe-Hesketh, S. (2004). Generalized latent variable modeling: Multilevel, longitudinal, and structural equation models. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2009). Report of the Commission of Experts of the President of the United Nations General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System. 2009. http://www.un.org/ga/econcrisissummit/docs/FinalReport_CoE.pdf. Accessed November 12 2014.

Topel, R., (2004). The private and social values of education. Proceedings from Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/conferences/2004/november/pdf/topel.pdf. Accessed November 12 2014.

Wagle, U. (2005). Multidimensional poverty measurement with economic well-being, capability, and social inclusion: A case from Kathmandu Nepal. Journal of Human Development, 6, 301–328.

Wolfle, L. M. (1980). The enduring effects of education on verbal skills. Sociology of Education, 53, 104–111.

Zack, M. M., Moriarty, D. G., Stroup, D. F., Ford, E. S., & Mokdad, A. H. (2004). Worsening trends in adult health-related quality of life and self-rated health—United States, 1993–2001. Public Health Reports, 119, 493–505.

Zheng, H., Yang, Y., & Land, K. C. (2011). Variance function regression in hierarchical ageeperiodecohort models: Applications to the study of self-reported health. American Sociological Review, 76, 955–983.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Lin, H. & Lin, YC. Education, Intelligence, and Well-Being: Evidence from a Semiparametric Latent Variable Transformation Model for Multiple Outcomes of Mixed Types. Soc Indic Res 125, 1011–1033 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0865-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0865-1