Abstract

Disparities in length of schooling between the largest Muslim minority in China, the Hui, and the Han majority are investigated. We use household data collected in Ningxia autonomous region in 2007. It is found that compared with Han persons of the same age and gender, Hui persons have shorter educations with the exception of young and middle-aged urban males who have 12 years of schooling, on average. Particularly noteworthy is that as many as 45 % of adult rural Hui females are not literate. Possible reasons for the shorter educations of Hui in many segments of the population are numerous. We show that the incentive to invest in length of schooling is smaller among Hui than Han as the association between education and income is weaker. We also report that Hui parents spend fewer resources on education than Han parents and that fewer years of schooling for Hui in the first generation helps to explain why Hui persons in the second generation have shorter educations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For an overview of the research on education of minority groups in China see Postiglione (2009).

According to World Value Study 2005 not less than 90 percent of Chinese respondents agreed more with the statement” Ethnic diversity enriches life” than the statement” Ethic diversity erodes a country’s unity”, see http://www.wvsevsdb.com/wvs/WVSDocumentation.jsp?Idioma=I

See Hannum (2002) who reports enrolment rates among children aged 7–12 in 1992 for 17 minority groups. Tibetan and Hui are found to have the lowest enrolment rates.

The number of county level units in each city are: Yinchuan: 6, Shuizuishan and Zhongwei: each 3, Wuzhong and Guyuan each 5. Data on education expenditures and total expenditures refer to the preceding year, 2006.

The total number of Hui persons in the sample is 2,257 of which 1,732 are from the southern part of Ningxia (Wuzhong, Guyuan and Zhongwei) representing 76.7 % of all Hui in the sample.

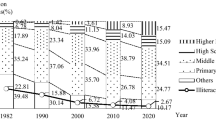

The Census 2000 also reports education by gender in rural as well as urban Ningxia. Our estimates show generally higher proportions of people with longer educations, which most probably is because they refer to 2007; an expansion of education took place between 2000 and 2007.

Census data for Ningxia 1990 cited by Bhalla and Qiu (2006) shows that as many as 65 % of female minority persons in Ningxia were illiterate at that time. Only Tibet, Gansu and Qinghai had higher illiteracy rates for female minorities.

Please note that we classify persons according to where they live at the time of the survey. Some of the people who are questioned in the urban survey grew up in rural Ningxia. This means that not only urban circumstances have generated the educational disparities (or lack of disparities) in urban Ningxia. Furthermore, the education gaps we report for rural Ningxia do not consider the population which has left the region for urban areas or for locations outside Ningxia.

Our data shows that most teenagers not in education were in employment. Using data from the China Household Income project (CHIP) 1988 and 1995 Bhalla and Qiu (2006) shows that for children aged 13–18 and living with parents, minority status had a negative effect on education attainment in rural China after controlling for other characteristics such as education of household head, spatial variables and household per capita income.

This assumes that all person observed in the rural born are also rural born. This assumption is most probably true in almost all cases as migration to rural areas is very limited among persons who are born in an urban area with an urban hukou (residents permit).

This is consistent with what Li and Ding (2013) report from earnings function analysis for urban residents (rural or urban born) using the same data.

There is now a growing literature attempting to establish a causal relationship between the education of parents and their children that uses one out of three strategies: by analysing identical twins, studying adoptees and using instrumental variables. In the last strategy, education reform has often been used as instrument for education. Holmlund et al (2011) summarises the literature and concludes for example, that for all studies surveyed, causal effects are smaller than cross-section estimates.

Our samples are not ideal for studying the intergenerational link in length of education, as some rural-born people have migrated to the cities, and migration can be supposed to be influenced by length of education. Note that some of the people in the urban sample are not urban-born.

In the Appendix we report Gini coefficients for length of schooling in the four rural and urban birth cohorts. The Gini coefficient is an inequality index often used when analysing the distribution of income. It takes values from 0, standing for complete equality, to 1 representing maximum inequality. The table shows that inequality in years of schooling reduced across cohorts, with the exception of that between the two youngest cohorts in urban Ningxia. The table also shows that inequality in years of education is smaller in urban Ningxia than in rural Ningxia.

The numbers of years of education among adult persons was for rural China: Kazakhs 7.2, Han 6.6, Uighur 6.1, Kyrgyz, 6.0, Hui 4.5, Salar 2.5 and Dongxian 1.5. Estimates for urban China are 11.1 years for Kazak, 10.5 years for Uighur, 10.4 for Han and 9.9 for Hui. There are too few observations among other minorities in the 2005 sample survey to make estimates meaningful. We thank Xiuna Yang for having made those computations.

References

Bai, G., Yan, X. and Li, X. (2006) “Multiple Difficulties and Countermeasures on the Development of the Hui Nationalities’ Education in Ningxia”, Value Engineering, 10, 248–249 (In Chinese).

Bhalla, A. S., & Qiu, S. (2006). Poverty and inequality among Chinese minorities. London, New York: Routledge.

Chang, H. Y. (1987). The Hui (Muslim) minority in China: An historical overview. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 8, 62–78.

Chuah, O. (2004). Muslims in China: The social and economic situation of Hui. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 24, 155–162.

Demurger, S., & Wan, H. (2012). Payments for ecological restoration and internal migration in China: The sloping land conversion program in Ningxia. IZA Journal of Migration, 1, 10.

Hannum, E. (1999). Political change and the urban-rural gap in basic education in China, 1949–1990. Comparative Education Review, 43, 193–211.

Hannum, E. (2002). Educational stratification by ethnicity in China: Enrolment and attainment in the early years. Demography, 39, 95–117.

Hannum, E., Behrman, J., Wang, M., & Liu, J. (2008). Education in the reform era. In L. Brandt & T. Rawski (Eds.), China’s great economic transformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hannum, E., & Wang, M. (2012). China. A case study in rapid poverty reduction. In G. Hall & H. Patrinos (Eds.), Indigenous peoples, poverty and development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holmlund, H., Lindahl, M., & Plug, E. (2011). The causal effect of parents’ schooling on children’s schooling. Journal of Economic Literature, 49, 615–651.

Knight, J., Sicular, T., & Yue, X. (2013). Educational inequality in China: The intergenerational dimension. In S. Li, H. Sato, & T. Sicular (Eds.), Rising inequality in China. Challenges to a harmonious society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Li, S., & Ding, S. (2013). An empirical analysis of income inequality between a minority and the majority in urban China: The case of Ningxia Hui autonomous region. Review of Black Political Economy, 40, 341–355.

Li S. and Wang Y. (2003) The Choice made when faced with the Dilemma in Hui nationalities’ education at present, Researches on the Hui, 2, 100–106. General No. 50. (In Chinese).

Lipman, J. (1997). Familiar strangers. A History of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Lu, Y., & Treiman, D. (2008). The effect of sibship size on educational attainment in China: Period variations. American Sociological Review, 73, 813–834.

Ma, X. (2006) On social changes and development of religious education in Linxia Ningxia Hui autonomous region, Journal of the Second North West University for Nationalities, 4, 50–54. General No. 72. (In Chinese).

Matsumoto, M., & Shimbo, A. (2011). “Islamic education in China. Triple discrimination and the challenge of Hui women’s madrasas”. In K. Sakurai & F. Adelkhak (Eds.), The moral economy of the madrasa. Islam and education today (pp. 85–102). Oxton: Routledge.

Merkle, R. (2003). Ningxia’s third road to rural development: Resettlement schemes as a last means to poverty Reduction? Journal of Peasant Studies, 30, 160–191.

Ningxia Daily (2012) “Ningxia University Examination Policy in 2012”, May 6, http://www.nxnet.cn/olddate/nxrb/2012-05/16/.

Postiglione, G. (2009). The education of ethnic minority groups in China. In J. Banks (Ed.), The Routledge international companion to multicultural education. New York, London: Routledge.

Sicular, T., Yue, X., Gustafsson, B., & Li, S. (2007). The urban—rural income gap and inequality in China. Review of Income and Wealth, 53, 93–126.

Sun, B. (2009) “Returns to education of different Nationalities: A Comparison of the Han, Tibetan and Hui Nationalities”, Journal of Research on Education for Ethnic Minorities, 5(20), 40–43. General No. 94. (In Chinese).

Hertz, T. Jayasundera, T., Pirano, P., Selcuk, S., Smith, N., Verashchagina, A. (2007) The Inheritance of Educational Inequality: Intergenerational Comparisons and Fifty-year Trends, B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 7(2) Article 10.

Teng, W., & Ma, X. (2009). Preferential policies for ethnic minorities and educational equality in higher education in China. In M. Zhou & A. Maxwell Hill (Eds.), Affirmative action in China and the US: A dialogue on inequality and minority education. Pelgrave Macmillan: New York.

Wang, T. (2007). Preferential policies for ethnic minority students in China’s College/University admission. Asian Ethnicity, 8, 149–163.

Whyte, M. K. (2010). One Country, Two Societies. Rural-Urban Inequality in Contemporary China. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press.

Zang, X. (2008). Market reform and Han-Muslim variation in employment in the Chinese state sector in a Chinese City. World Development, 36, 2341–2352.

Zang, X. (2007). Ethnicity and urban life in China. A comparative study of Hui Muslims and Han Chinese. London, New York: Routledge.

Zhang, L., Tu, Q., & Mol, P. J. (2008). Paying for environmental services: The sloping land conversion program in Ningxia autonomous region of China. China and World Economy, 16, 66–82.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gustafsson, B., Sai, D. Mapping and Understanding Ethnic Disparities in Length of Schooling: The Case of the Hui Minority and the Han Majority in Ningxia Autonomous Region, China. Soc Indic Res 124, 517–535 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0806-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0806-4