Abstract

Today, though the need for new indicators of progress is broadly recognized, no consensus has arisen on a successor to gross domestic product (GDP). Various quantification options are debated. While some intend to improve current indicators by completing or adjusting them to new constraints, others think that new indicators of progress are liable, if well-designed, to catalyse a transition toward a new societal model, less reliant on growth. Up to now, the normative stakes related to quantification options, though crucial for “what we measure affects what we do”, are scattered among the debates and do not appear clearly to actors. Our paper aims therefore to offer a systematic understanding of the normative impacts of generic quantification choices. To that end, we analyse the index of economic well-being (IEWB). For each dimension of this composite indicator, the analysis—which aims to be easily transposed to other indicators—sheds light on the variety of normative implications resulting from its conceptual and methodological apparatus. This concomitantly leads us to question in depth the relevance of some theoretical hypotheses underlying the IEWB to coherently account for economic, social and ecological issues. The paper’s conclusion suggests that alternative conceptual frameworks, such as ecological economics and the capability approach, are liable to carry more coherent indicators of progress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Such as the OECD, the World Bank and the EU.

Let us mention the influential Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress ("the Stiglitz commission"), chaired by Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi, launched in January 2008 by the President of France, Sarkozy.

The commission CAE-CGEE (launched in 2009 by Merkel and Sarkozy) questions: "How can we broaden our perspective from its current focus on economic performance to an assessment of the quality of life more generally, in order to appreciate what really counts for human welfare?" (CAE-CGEE 2010: 5). The European Commission recognizes that: "Critically, GDP does not measure environmental sustainability or social inclusion and these limitations need to be taken into account when using it in policy analysis and debates"(European Commission, 2009: 3).

See FAIR (2011) for a good overview of the various initiatives at stake.

It is worth mentioning that the normative scope of quantification choices raises a strong democratic issue at the procedural level: who is legitimate to define what progress is? This question has been at the origin of numerous studies (see FAIR 2011). Purposely we do not focus here on this procedural level, in order to study in depth the technical aspects of the normative scope of quantification.

Linear scaling is used to standardize the range of a variable. In the case of the IEWB, an estimate is made for the high and low values for all time periods and/or for all countries analyzed (denoted Min and Max, respectively). The data is then scaled according to these values. If a variable increase corresponds to an increase in economic well-being, the variable (Value), is scaled according to the formula (Value − Min)/(Max − Min). If, in contrast, an increase in (Value) corresponds to decrease in economic well-being, the Value is scaled according to (Max − Value/Max − Min). For more details, see Salzman (2004) and Jany-Catrice and Kampelmann (2007).

Illustratively, the authors, on the CSLS website suggest various weighting schemes in their spreadsheets among which a weighting giving much weight to consumption [0.4, (CF), 0.1 (WS), 0.25 (ID) and 0.25 (ES)] and an equal weighting [0.25, (CF), 0.25 (WS), 0.25 (ID)) and 0.25 (ES)].

ISEW = personal consumption + public non-defensive expenditures − private defensive expenditures + capital formation + services from domestic labour − costs of environmental degradation − depreciation of natural capital; GPI = Personal consumption adjusted for income inequalities + Value of housework and parenting + Services of consumer durables + Services of highways and streets + Value of volunteer work + Net capital investment − Cost of household pollution abatement − Cost of noise pollution − Cost of crime − Cost of air pollution − Cost of water pollution − Cost of family breakdown − Loss of old-growth forests − Cost of underemployment − Cost of automobile accidents − Loss of farmland − Net foreign ending or borrowing − Loss of leisure time − Cost of ozone depletion − Loss of wetlands − Cost of commuting − Cost of consumer durables − Cost of long term environmental damage − Depletion of non-renewable resources. See Brian et al. (2003: 8) for a synthetic overview of the differences between ISEW and GPI.

The real value of changes in working time is indicated by the imputed value of leisure per capita with unemployment adjustment (1996$). The latter is computed as the product of the average after tax compensation per employed person per hour, the working age population as a percentage of the total population, and the average annual number of hours of unemployment per person aged 15–64 relative to the 1971 benchmark year. The average after tax compensation per employed person per hour = (1 − (General Government Current Receipts, as a Percentage of Nominal GDP/100)) * Average Compensation per Employed Person per Hour. The average annual number of hours of unemployment per Person Aged 15–64 = ((Average annual number of hours worked per person * Employment over Working Age Population Ratio, %)/100) * Average Annual Number of Hours of Unemployment per Person Aged 15–64.

In Osberg and Sharpe compute this dimension as (C + UP + G + WT) * (LE), where C is the real per capita consumption adjusted for regrettable costs. For the sake of clarity, we have decided to make this adjustment explicit in the formula.

Index of equivalent income (US 1971 = 1.00) = Square Root of Family size/Square Root of family size in US 1971 (Note: Index of Equivalent Income was calculated on the basis of one half rate of change of family size.) Source: Census Data, http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/htabHH-6.txt.

The use of deflators is not neutral and would deserve some attention, in the fact that deflators and price consumption indices, on one hand, imperfectly reflect quality changes and, on the other, are generally based on average baskets of goods, not considering distributional issues related to the way changes in certain prices (basic goods for instance) affect the economic well-being of specific socioeconomic categories. But it exceeds the aim of that paper. See Stiglitz et al. (2009) and Conseil National de l'Information Statistique (2006).

Crime is accounted as "the cost of crime to victims based on their out-of-pocket expenditures or the value of stolen property" (Anieleski and Rowe 1999: 18). Costs of commuting encompasses: "the money spent to pay for the vehicle, or for bus or train fare" and "the time lost that might have been spent on other, more enjoyable or productive activities" (Ibid. 1999: 28). Costs of household pollution abatement are the expenditures made for equipments and other defensive expenditures aimed to compensate for pollution. Costs of automobile accidents account the economic losses which "cover only motor vehicle accidents on and off the road and all injuries regardless of length of disability. Economic loss includes wage loss; legal, medical, hospital, and funeral expenses; insurance administration costs; and property damage." (Ibid. 1999: 31).

For now this problem appears mostly theoretical: given problems of data availability across countries, and the resulting lack of comparability, this dimension has been retrieved from the index.

"Unpaid productive work such as domestic work and child care should be included, where appropriate, in satellite national accounts and economic statistics" (Agenda 21, Chapter 8, http://www.gdrc.org/decision/agenda21chapter8.html).

See Cassiers and Thiry (2014).

This discussion might be addressed to many other indicators, such as the ISEW and the GPI.

LIM means Low-Income Measure, whereby the poverty line is defined as a fixed proportion of the median income.

More precisely, the Gini index measures the area between the Lorenz curve (which plots on the y axis the proportion of the total income of the population that is cumulatively earned by the bottom x % of the population) and the hypothetical line of absolute equality, expressed as a percentage of the maximum area under the line. (See http://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=4842).

See OCDE 2011 for examples of multi-dimensional joint distributions.

See http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ for more details.

For a deeper analysis of the sustainability dimension of a different indicator (Adjusted Net Savings), see Thiry and Cassiers (2010).

This question is explored in detail in Thiry and Cassiers (2010).

α is the normalized proportion of the population aged 15–64 in the total population, β is the normalized proportion of the population at risk of illness (=100 %), γ is the normalized proportion of the population comprised of married women with children under 18, δ is the normalized proportion of the population in immediate risk of poverty in old age.

In the present case, a variation in average outcomes can uneasily compensate for a variation in inequalities; at least, the foundation of such a possibility of substitution should be explicitly questioned.

This ethical/conceptual framework is the object of the chapter 5 of Thiry (2012).

Gaudet (2007) explore the slope of the resources price path in different market structures. He shows that as soon as imperfections are introduced (he studies monopoly and oligopolistic competition respectively), the price path is flatter than in perfect competition.

We study in detail the contribution of ecological economics in the construction of new indicators of progress in another ongoing paper.

"Le défi posé par l’articulation des inégalités écologiques et des inégalités sociales est complexe en ce que la discussion porte tant sur la définition de ce qui est " bien " et de ce qui est " mal " (…) que sur leur répartition."(p. 1).

This opens up a broad questioning on the contribution of indicators' analysis, through their specific epistemological position at the edge of theory and of empirical experience, in the criticism of weak sustainability. This question is treated in chapter 5 of Thiry (2012).

References

Alkire, S. (2002). Sen's capability approach and poverty reduction. In Valuing freedoms (356. p). Oxford University Press:New York.

Alkire, S., & Santos, M., E. (2010). Multidimensional Poverty Index. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative.

Anand, P., Hunter, G., & Smith, R. (2005). Capabilities and well-being: Evidence based on the sen-Nussbaum approach to welfare. Social Indicator Research, 74(1), 9–55.

Anieleski, M., & Rowe, J. (1999). The Genuine Progres Indicator—1998 update, Redefining Progress.

Arrow, K., Dasgupta, P., Goulder, L., Daily, G., Ehrlich, P., Heal, G., et al. (2004). Are we consuming too much? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(3), 147–172.

Aubrée, L., & Bonduelle, A. (2011). L’équité au cœur des politiques climatiques: l’exemple des négociations relatives au climat et de la recherche de solutions à la crise énergétique. Développement durable et territoires, 2(1). http://developpementdurable.revues.org/8822.

Balestrino, A. (1996). A note on functionings-poverty in affluent societies. Notizie di Politeia, 12, 97–105.

Baudrillard, J. (1996). La société de consummation. Ed. Gallimard, Coll. Folio, 1st Ed. 1970.

Bosello, F., Portale, E., Campagnolo, L., Eboli, F., & Parrado, R. (2011). WP6: Costs of sustainability (general equilibrium analysis), D6.5: Sustainability index analysis. In Seventh Framework Programme, Theme FP7-ENV-2007-1.

Brian, J., Hou, J., Milder, J., & Upton, M. (2003). Alternative indicators of economic welfare. Environmental strategies, NTRES 454, Cornell University December 12, 2003. http://www2.dnr.cornell.edu/saw44/NTRES431/Products/Fall%202003/Module2/AEIessay.pdf.

CAE-CGEE. (2010). Monitoring economic performance, quality of life and sustainability. Joint report as requested by the Franco-German Ministerial Council.

Cassiers, I., & Delain, C. (2006). La croissance ne fait pas le bonheur: les économistes le savent-ils? Regards Economiques, 38, 14p.

Cassiers, I., & Thiry, G. (2014). A high-stakes shift: Turning the tide from gdp to new prosperity indicators. In I. Cassiers (Ed.), Redefining prosperity. London: Routledge.

Chiappero-Martinetti, E. (2003). Unpaid work and household well-being. In A. Picchio (Ed.), Unpaid Work and the Economy: A Gender Analysis of the Standards of Living. London: Routledge.

Čiegis, R., & Grundey, D. (2005). Economic competition and the sustainability paradigm: Concepts of strong comparability and commensurability versus concepts of strong and weak sustainability. Economic issues in practice, Vol. 3, Macro and microeconomics, case studies (pp. 77–112). Szczecin: University of Szczecin.

Conseil National de l’Information Statistique. (2006). Niveau de vie et inégalités sociales, December 2006.

Costanza, R., Alperovitz, G., Daly, H., Farley, J., Franco, C., Jackson, T., et al. (2013). Building a sustainable and desirable economy-in-society-in-nature. Report to the United Nations as part of the sustainable development in the 21st century (SD21) project implemented by the Division for Sustainable Development of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Costanza, R., Cumberland, J., Daly, H., Goodland, R., & Norgaard, R. (2007). An introduction to Ecological Economics. The Encyclopedia of Earth, E-book. http://www.eoearth.org/article/An_Introduction_to_Ecological_Economics_%28e-book%29.

Daly, H. (1968). On economics as a life science. Journal of Political Economy, 76, 392–406.

Daly, H., & Cobb, J. (1989). For the common good. Boston: Beacon Press.

Daly (1999). Ecological economics and the ecology of economics (p. 191), Edward elgar.

De Munck, J. (2011). Les critiques du consumérisme. In Cassiers, I. (Ed.), Redéfinir la prospérité. Jalons pour un débat public (101–126). Paris: de L’Aube, Coll. Monde en cours.

Dervis, K., & Klugman, J. (2011). Measuring human progress: the contribution of the Human Development Index and related indices. Revue d’économie politique, 121(1), 73–92.

Downward, P. (2004). On leisure demand: A post Keynesian critique of neoclassical theory. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 26(3), 371–394.

Easterlin, R. E. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. et Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz. London: Academic Press.

European Commission. (2009). GDP and beyond. Measuring progress in a changing world. Communication from the commission to the council and the European parliament, COM 2009 (433).

FAIR. (2011). La richesse autrement. Alternatives Economiques. Hors-Série Poche, 48.

Ferreira, S., & Vincent, J. (2005). Genuine savings: Leading indicator of sustainable development? Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53(3), 737–754.

Fleurbaey, M., & Blanchet, D. (2013). Beyond GDP. Measuring welfare and assessing sustainability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flipo, F. (2009). Les inégalités écologiques et sociales: l’apport des théories de la justice. Mouvements, 60, 59–76.

Gadrey, J. (1997). Croissance et productivité: des concepts obsolètes? In Compte rendu de conférence “Les amis de l’Ecole de Paris”.

Gadrey, J. (2010). Adieu à la croissance. Bien vivre dans un monde solidaire. Paris: Les petits matins.

Gadrey, J. and Jany-Catrice, F. (2012). Les nouveaux indicateurs de richesse, 3rd ed. Paris: La découverte, Coll. Repères.

Gaudet, G. (2007). Natural resource economics under the rule of hotelling. Presidential address delivered at the 41st annual meetings of the Canadian Economics Association, Halifax, 2 June 2007.

Harribey (2009). Commission Stiglitz : l’économie, la montagne et la souris Alternative économique. http://www.alternatives-economiques.fr/blogs/harribey/2009/.

Jackson, T. (2009). Prosperity without growth. Economics for a finite planet. Earthscan.

Jany-Catrice, F., & Kampelmann, S. (2007). L’indicateur de bien-être économique: une application à la France. Revue française d’économie, 22(1), 107–148.

Jany-Catrice, F., & Méda, D. (2011). Femmes et richesse: au-delà du PIB. La Découverte: Travail, Genre et Société, 26(2), 147–171.

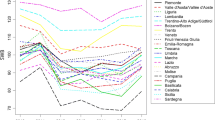

Jany-Catrice, F., & Zotti, R. (2009). Un indicateur de santé sociale pour les régions françaises. Futuribles, 350, March 2009.

Kuklys, W. (2005). Amartya Sen’s capability approach: Theoretical insights and empirical applications. Studies in Choice and Welfare, Vol.18 (pp. 116).

Luxton, M. (1997). The UN, women, and household labour: measuring and valuing unpaid work. Women’s Studies International Forum, 20(3), 431–439.

Martinez-Alier, J. (1987). Ecological economics: energy, environment, and society. New York: Blackwell.

Martinez-Alier, J., Munda, G., & O’Neill, J. (1998). Weak comparability of values as a foundation for ecological economics. Ecological Economics, 26, 277–286.

Méda, D. (2008). Au-delà du PIB. Pour une autre mesure de la richesse (Vol. 796). Paris: Flamarion, Coll. Champs (1st ed. 1999).

Nordhaus, W., & Tobin, J. (1973). Is Growth Obsolete? The measurement of economics and social performance, studies in income and wealth, 38, 509–564.

Nussbaum, M. (2003). Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice. Feminist Economics, 9(2–3), 33–59.

OECD. (2007). Istanbul declaration. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/14/46/38883774.pdf.

OECD. (2009). Growing unequal? Income Distribution and poverty in OECD countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2011). Towards green growth. Paris: OECD Publishing.

O’Neill, J. (2004) [1993]. Ecology, policy and politics: Human well-being and the natural world. London: Routledge.

Osberg, L. (1985). The measurement of economic well-being. In Laidler, D. (Ed.). Approaches to economic well-being, vol. 26 of the Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada (MacDonald Commission). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Osberg, L. (2009). Measuring economic security in insecure times: New perspectives, new events, and the index of economic well-being. CSLS Research Report 2009-12.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (1998). An index of economic well-being for Canada. Applied Research Branch Strategic Policy Human Resources Development Canada.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2001). Comparisons of trends in gross domestic product and economic well-being—The impact of social capital. In The contribution of human and social capital to sustained economic growth and well-being: International symposium report, edited by John Helliwell with the assistance of Aneta Bonikowska, OECD and Human Resources Development Canada.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2002a). The index of economic well-being. Indicators: The Journal of Social Health, 1(2), 24–62.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2002b). An index of economic well-being for selected OECD Countries. The Review of Income and Wealth, 48(3), 291–316.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2002c). International comparisons of trends in economic well-being. Social Indicators Research, 58(1–3), 349–382.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2003). Human well-being and economic well-being: what values are implicit in current indices? CSLS Research Reports 2003-04, Centre for the Study of Living Standards (60. p).

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2005). How should we measure the economic aspect of well-being? Review of Income and Wealth, 51(2), 311–336.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2009). New estimates of the index of economic well-being for selected OECD countries, 1980-2007, CSLS Research Report 2009-2011, Centre for the Study of Living Standards (106. p).

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2011). Moving from a GDP-based to a well-being based metric of economic performance and social progress: Results from the index of economic well-being for OECD countries, 1980–2009. CSLS Research Report 2011-12.

Pezzey, J. (1992). Sustainable development concepts: An economic analysis. World Bank environment paper (Vol. 2).

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of Justice. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Robeyns, I. (2003). Sen’s capability approach and gender inequality: Selecting relevant capabilities. Feminist Economics, 9, 61–92.

Robeyns, I. (2005). Selecting capabilities for quality of life measurement. Social Indicators Research, 74(1), 191–215.

Robeyns, I. (2008). How has the capability approach been put into Practice? E-Bulletin of Human Development and Capability Association, 12, 3–6.

Saltelli, A. (2007). Composite Indicators between analysis and advocacy. Social Indicators Research, 81(1), 65–77.

Salzman, J. (2004). Methodological choices encountered in the construction of composite indices of economic and social well-being. Ottawa: Center for the Study of Living Standards.

Sharpe, A., Méda, D., Jany-Catrice, F., & Perret, B. (2003). Débat sur l’indice du Bien-être économique. Travail et Emploi, 93, 75–111.

Social Science Research Council (SSRC). (2008). In S. Burd-Sharps, K, Lewis, EB Martins (Eds.), The measure of America: American human development report 2008–2009. New York: SSRC, Columbia University Press.

Spangenberg, J. (2007). Defining sustainable growth: The inequality of sustainability and its applications. In Antonello, S. (Dir.), Frontiers in ecology research (pp. 97–140).

Stanton, E. A. (2007). The human development index: A history. Political economy research institute working paper, Vol. 127.

Stewart, F. (2001). Women and human development: The capabilities approach by Martha C. Nussbaum. Journal of International Development, 13(8), 191–192.

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2009). Report of the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress.

Sugden, R. (1993). Welfare, resources, and capabilities: A review of Inequality Re-examined by Amartya Sen. Journal of Economic Literature, XXXVI, 1947–1962.

Szoc, E. (2011). La taille du gâteau et l’assiette du voisin: ce que Jackson fait à Rawls. Etopia, Revue d’écologie politique, 9, 93–98.

Thiry, G. (2012). Au-delà du PIB: un tournant historique. Enjeux méthodologiques, théoriques et épistémologiques de la quantification. Ph.D. Dissertation, Director: I. Cassiers.

Thiry, G. & Cassiers, I. (2010). Alternative indicators to GDP : values behind numbers. Adjusted net savings in question. IRES discussion paper. 2010-18.

Van den Bergh, J. (2007). Abolishing GDP. Tinbergen institute discussion paper, TI 2007-019/3.

van den Bergh Jeroen, C. J. M., (2009). The GDP Paradox. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(2), 117–135.

Veblen, T. (1994) [1899]. The theory of the leisure class. Penguin twentieth-century classics, Introduction by Robert Lekachman, Penguin Books.

Wolff, J., & de-Shalit, A. (2007). Disadvantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zaidi, A., & Burchardt, T. (2005). Comparing incomes when needs differ: Equivalization for the extra cost of disability in the U.K. Review of Income and Wealth, 51, 89–114.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thiry, G. Beyond GDP: Conceptual Grounds of Quantification. The Case of the Index of Economic Well-Being (IEWB). Soc Indic Res 121, 313–343 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0650-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0650-6