Abstract

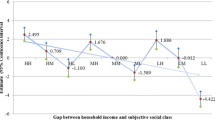

The study investigates the health effects of subjective class position stratified by objective social position. Four types of subjective class were analysed separately for individuals with manual or non-manual occupational background. The cross-sectional analysis is based on the Swedish Level-of-Living Survey from 2000 and includes 4,139 individuals. The dataset comprises information on perceived class affinity and occupational position that was combined to conduct logistic regression models on self-rated health. An inverse relationship between self-rated health and the eight combinations of objective and subjective social position was found. Lower socio-economic position was associated with poor health. The largest adverse health effects were found for lower subjective social position in combination with lower occupational position. When the covariates education, father’s occupational position and income were added to the model, adverse effects on health remained only for females. Subjective social position helps to explain health inequalities. Substantial gender differences were found. It can be assumed that subjective class position captures a wide range of perceived inequalities and therefore complements the measure of occupational position.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Åberg Yngwe, M. (2005). Resources and relative deprivation. Analysing mechanisms behind income, inequality and ill-health. Stockholm: Stockholm University/Karolinska Institutet.

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592.

Adler, N. E., & Ostrove, J. M. (1999). Socioeconomic status and health: What we know and what we don’t. Socioeconomic Status and Health in Industrial Nations, 896, 3–15.

Burström, B., & Fredlund, P. (2001). Self rated health: Is it as good a predictor of subsequent mortality among adults in lower as well as in higher social classes? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55(11), 836–840.

Charles, N. (1990). Women and class—a problematic relationship. Sociological Review, 38(1), 43–89.

Demakakos, P., Nazroo, J., Breeze, E., & Marmot, M. (2008). Socioeconomic status and health: The role of subjective social status. Social Science and Medicine, 67(2), 330–340. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038.

Eibner, C., Sturn, R., & Gresenz, C. R. (2004). Does relative deprivation predict the need for mental health services? J Ment Health Policy Econ, 7(4), 167–175.

Erikson, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1992). The constant flux: A study of class mobility in industrial societies. Oxford: Clarendon.

Goodman, E., Huang, B., Schafer-Kalkhoff, T., & Adler, N. E. (2007). Perceived socioeconomic status: A new type of identity that influences adolescents’ self-rated health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(5), 479–487. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.020.

Jylhä, M. (2009). What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. [Research Support, Non-US Gov’t]. Social Science and Medicine, 69(3), 307–316. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013.

Kondo, N., Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S. V., Takeda, Y., & Yamagata, Z. (2008a). Do social comparisons explain the association between income inequality and health?: Relative deprivation and perceived health among male and female Japanese individuals. Social Science and Medicine, 67(6), 982–987. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.002.

Kondo, N., Kawachi, I., & Yamagata, Z. (2008b). Relative deprivation and perceived health among Japanese working-age population: Exploring psychological pathways in income inequality and health. American Journal of Epidemiology, 167(11), S49–S49.

Kopp, M., Skrabski, A., Rethelyi, J., Kawachi, I., & Adler, N. E. (2004). Self-rated health, subjective social status, and middle-aged mortality in a changing society. Behavioral Medicine, 30(2), 65–70.

Lundberg, J., & Kristenson, M. (2008). Is subjective status influenced by psychosocial factors? Social Indicators Research, 89(3), 375–390. doi:10.1007/s11205-008-9238-3.

Lundberg, O., & Manderbacka, K. (1996). Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 24(3), 218–224.

Macleod, J., Davey Smith, G., Metcalfe, C., & Hart, C. (2005). Is subjective social status a more important determinant of health than objective social status? Evidence from a prospective observational study of Scottish men. Social Science and Medicine, 61(9), 1916–1929. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.009.

Matthews, S., Manor, O., & Power, C. (1999). Social inequalities in health: Are there gender differences? Social Science and Medicine, 48(1), 49–60.

Newman, D. N., & Tanner-Smith, E. E. (2008). Married persons’ subjective class identification: The role of individual gender ideologies from 1972 to 2002. Gender Issues, 25, 114–140. doi:10.1007/s12147-008-9052-x.

Pakulski, J., & Waters, M. (1996). The death of class. London: Sage.

Ritterman, M. L., Fernald, L. C., Ozer, E. J., Adler, N. E., Gutierrez, J. P., & Syme, S. L. (2009). Objective and subjective social class gradients for substance use among Mexican adolescents. Social Science and Medicine, 68(10), 1843–1851. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.048.

Sacker, A., Firth, D., Fitzpatrick, R., Lynch, K., & Bartley, M. (2000). Comparing health inequality in men and women: Prospective study of mortality 1986–96. BMJ, 320(7245), 1303–1307.

Sakurai, K., Kawakami, N., Yamaoka, K., Ishikawa, H., & Hashimoto, H. (2010). The impact of subjective and objective social status on psychological distress among men and women in Japan. Social Science and Medicine, 70(11), 1832–1839. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.019.

Singh-Manoux, A., Marmot, M. G., & Adler, N. E. (2005). Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(6), 855–861. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000188434.52941.a0.

Starrin, B., Aslund, C., & Nilsson, K. W. (2009). Financial stress, shaming experiences and psychosocial ill-health: Studies into the finances-shame model. Social Indicators Research, 91(2), 283–298. doi:10.1007/s11205-008-9286-8.

StataCorp. (2009). Stata statistical software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Statistics Sweden. (2009). Income distribution 2007: Incomes rose like never before. http://www.scb.se/Pages/PressRelease_263705.aspx. Accessed 9 Nov 2011.

Stronks, K., van de Mheen, H. D., & Mackenbach, J. P. (1998). A higher prevalence of health problems in low income groups: Does it reflect relative deprivation? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 52(9), 548–557.

Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2007). The problems of relative deprivation: Why some societies do better than others. Social Science and Medicine, 65(9), 1965–1978. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.041.

Williams, S. J. (1998). ‘Capitalising’ on emotions? Rethinking the inequalities in health debate. Sociology, 32(1), 121–139. doi:10.1177/0038038598032001008.

Wolff, L. S., Acevedo-Garcia, D., Subramanian, S. V., Weber, D., & Kawachi, I. (2010a). Subjective social status, a new measure in health disparities research: Do race/ethnicity and choice of referent group matter? J Health Psychol, 15(4), 560–574. doi:10.1177/1359105309354345.

Wolff, L. S., Subramanian, S. V., Acevedo-Garcia, D., Weber, D., & Kawachi, I. (2010b). Compared to whom? Subjective social status, self-rated health, and referent group sensitivity in a diverse US sample. Social Science and Medicine, 70(12), 2019–2028. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.033.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Olle Lundberg, Siegfried Geyer and Monica Åberg Yngwe for valuable comments. This study was funded by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miething, A. The Relevance of Objective and Subjective Social Position for Self-Rated Health: A Combined Approach for the Swedish Context. Soc Indic Res 111, 161–173 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9988-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9988-1