Abstract

This paper seeks to analyze the influence of the weather on a person’s self-reported life satisfaction. On a theoretical level, it is claimed that ‘nice’ weather can improve the affective well-being of a person. Given this, it is argued that affects can, in turn, have an impact on that person’s general assessment of his or her life. In particular, it is expected that people would report a higher life satisfaction on days with unambiguously ‘nice’ weather. Data from three German large-scale surveys are used to test empirically to what extent self-reported life satisfaction is determined by the weather. All in all, the results are mostly consistent with the initial hypothesis. In all three samples those respondents surveyed on days with exceptionally sunny weather reported a higher life satisfaction compared to respondents interviewed on days with ‘ordinary’ weather. In two out of three samples, this difference was statistically significant. Hence, the supposed sunshine effect on peoples’ life satisfaction does indeed exist. Implications of these findings are discussed in a conclusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Whereas personality psychologists mostly argue in favour of the first position, the second point of view was mainly investigated by scholars who represented the social cognition tradition. This latter school of thought tested, in particular, how ‘technical’ aspects of questionnaire design and of the interview situation influenced self-reported life satisfaction (item order effects, interviewer effects, etc.). These studies mostly documented consistent, but small effects on self-reports of life satisfaction (Schimmack and Oishi 2005). Furthermore, some studies investigated the relevance of mood-inducing events on peoples’ life satisfaction. The experiments by Schwartz cited at the outset of this paper are one example for this kind of research.

Participants in this study were put into three test conditions groups, so that 28 respondents were questioned per test condition. It seems noteworthy, though, that weather-induced differences in life satisfaction, as reported by Schwarz and Clore, are insignificant in two of the three test conditions. Strictly speaking, the popular belief that weather can affect a persons’ life satisfaction is based only on one tiny study with solely 28 respondents.

Affective well-being consists of both pleasant and unpleasant affects. Affects, in turn, consist of moods as well as emotions. Emotions differ from moods: "Because emotions arise from ongoing, implicit appraisals of situations with respect to their implications for one’s goals, they have an identifiable referent, a sharp rise time, and limited duration. These characteristics distinguish emotions from moods, which lack a clear referent, may come about gradually, may last for an extended time and are often of low intensity" (Schwarz 2011: 8).

In another study, Keller et al. (2005) demonstrate that warm and sunny weather only improves a subject’s mood if this person had spent more than 30 min outdoors. Thus, the sunshine effect on mood is positive, but only for those who are directly exposed to the weather. Contradictory results are reported by Watson (2000). In his research among students from Texas and Japan, no significant correlations between weather and moods are found. Neither sunshine nor air pressure, temperature or precipitation influenced the mood of the students.

Parker and Tavassoli (2000) argue that in climate zones with lower average sunshine, the level of serotonin has to be increased by other means. They can show, for example, that people consume more alcohol, coffee, chocolate and cigarettes in these regions.

Both the “affect-priming”-hypothesis and the “mood-as-information”-hypothesis have been proven many times, for example, in the context of the evaluation of probabilities and risks. In a study by Johnson and Tversky (1983), subjects who were in a bad mood overestimated the probability of death as a result of illness or natural disaster, while respondents in neutral moods came to fairly adequate estimations (see also Mayer et al. 1992; for more recent reviews Forgas 2008; Blanchette and Richards 2010).

Among others, this is a serious problem for researchers who try to simulate the development of life satisfaction under changing climatic conditions. In this regard, Frijters and Van Praag (1998: 75) note: “The problem becomes greatest when it comes to computing the effect of climate change upon well-being… Well-being is generated by the interaction of highly correlated [climate] variables, whose cause-and-result structure is unknown.”

For every respondent, the Eurobarometer (EB) includes information on the federal state (Bundesland) and the GGSS on the administrative district (Regierungsbezirk). To identify the city of residence, we had to combine this data with other information on the population size of the respondent’s residence. Considering both elements in combination allowed us to identify a couple of major German cities. For example, the federal state of Hesse has only one city with more than 500,000 inhabitants: Frankfurt on the Main. Other major cities, like Berlin, Hamburg or Munich, can be identified in a similar way. As the administrative district is a more specific type of information compared to the federal state, Study 3 (based on the GGSS) includes nine German cities whereas Study 1 and 2 (based on the EB) includes only five cities.

Only respondents of employable age answered the question that measures fulfillment with professional life.

Possible differences between the questions and the underlying constructs are discussed more precisely in the final section of this paper.

A more restrictive definition of a sunny day would have resulted in a very small number of respondents interviewed on sunny days.

In addition to the weather, other situational factors can impact general life satisfaction as well. As Schwarz et al. showed, such mundane events like finding an apparently overlooked coin at the copying machine can positively influence a person’s life satisfaction. Furthermore, it is possible that other situational factors moderate the impact of weather on life satisfaction. For instance, the mood-improving effect of sunny weather could be reinforced by another mood-improving event like a meeting with a good friend or could be diminished or distorted by negative events like losing your wallet. Unfortunately, we can not control for all these mood-inducing events because there is no information about these events in our data. However, this should not be a problem for our research because of the fortuitous occurrence of such mood-inducing events. Instead, it could be assumed that the influence of these situational factors is balanced out unless they are produced systematically by the research design itself or by the interview situation. Therefore, additional controls of other situational factors would be helpful (particularly to compare the various effects), but are in no way necessary.

Cautiously speaking, studies which use this particular question for measuring subjective well-being are not very numerous. Aside from the EB 67.1 wave that we analyzed here, we do not know any other study.

Another explanation for a supposedly weaker or even negative effect of sunshine in summer months is given by Cohen (2011). He speculates that „the positive effects of sunlight on mood should be naturally minimal during the summer, because the length of summer days naturally offsets melatonin production, which dramatically reduces the positive effects of sunlight.” Furthermore, Cohen reasons that sunlight during the summer may have a negative effect on mood due to the hot temperatures that accompanies sunshine in summer. Very hot temperatures should reduce the affective well-being of a person. Some studies even demonstrated that irritability (Holland et al. 1985), aggression (Berkowitz 1993) and even suicides are a side-effect of hot temperatures (Barker et al. 1994; Page et al. 2007).

References

Barker, A., Hawton, K., Fagg, J., & Jennison, C. (1994). Seasonal and weather factors in Parasuicide. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 375–380.

Becchetti, L., Castriota, S., & Londono Bedoya, D. A. (2007). Climate, happiness and the kyoto protocol: Someone does not like it hot. CEIS Working Paper, No. 247. University of Rome Tor Vergata.

Berkowitz, L. (1993). Pain and aggression: Some findings and implications. Motivation and Emotion, 17, 277–294.

Blanchette, I., & Richards, A. (2010). The influence of affect on higher level cognition: A review of research on interpretation, judgement, decision making and reasoning. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 561–595.

Canbeyli, R. (2010). Sensorimotor modulation of mood and depression: An integrative review. Behavioural Brain Research, 207, 249–264.

Clore, G. L., & Huntsinger, J. R. (2007). How emotions inform judgment and regulate thought. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 393–399.

Cohen, A. (2011). The photosynthetic president: Converting sunshine into popularity. Social Science Journal, 48, 295–304.

Compton, R. J., Wirtz, D., Pajoumand, G., Claus, E., & Heller, W. (2004). Association between positive affect and attentional shifting. Cognitive Research and Therapy, 28, 733–744.

Denissen, J. J. A., Butalid, L., Penke, L., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2008). The effects of weather on daily mood: A multilevel approach. Emotion, 8, 662–667.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–572.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Even, C., Schroder, C. M., Friedman, S., & Roullion, F. (2008). Efficacy of light therapy in nonseasonal depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 108, 11–23.

Forgas, J. (2008). Affect and cognition. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 94–101.

Frijters, P., & van Praag, B. M. S. (1998). The effects of climate on welfare and well-being in Russia. Climate Change, 39, 61–81.

Greifeneder, R., Bless, H., & Pham, M. T. (2010). When do people rely on affective and cognitive feelings in judgment? A review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20, 1–35.

Guven, C. (2009). Weather and financial risk-taking: is happiness the channel? SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research (Vol. 218). Berlin: DIW.

Harmatz, M. G., Well, A. D., Overtree, C. E., Kawamura, K. Y., Rosal, M., & Ockene, I. S. (2000). Seasonal variation of depression and other moods: A longitudinal approach. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 15, 344–350.

Holland, R., Sayers, J., Keatinge, W., Davis, H., & Peswani, R. (1985). Effects of raised body temperature on reasoning, memory, and mood. The Journal of Applied Physiology, 59, 1823–1827.

Isen, A. M. (2008). Some ways in which positive affect influences decision making and problem solving. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. Feldman Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of Emotions (pp. 548–573). New York: Guilford.

Jacobsen, F. M., Wehr, T. A., Sack, D. A., James, S. P., & Rosenthal, N. E. (1987). Seasonal affective disorder. A review of the syndrome and its public health implications. American Journal of Public Health, 77, 57–60.

Johnson, E. M., & Tversky, A. (1983). Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 20–31.

Keller, M. C., Fredrickson, B. L., Ybarra, O., Coté, S., Johnson, K., Mikels, J., et al. (2005). A warm heart and a clear head: The contingent effects of weather on mood and cognition. Psychological Science, 16, 724–731.

Kripke, D. F. (1998). Light treatment for nonseasonal depression: Speed, efficacy, and combined treatment. Journal of Affective Disorders, 49, 109–117.

Kuppens, P., Realo, A., & Diener, E. (2008). The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 66–75.

Leppämäki, S., Partonen, T., & Lönnqvist, J. (2002). Bright-light exposure combined with physical exercise elevates mood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 72, 139–144.

MacLeod, C. (1999). Anxiety and anxiety disorders. In T. Dalgeish & M. J. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion (pp. 447–477). New York: Wiley.

MacLeod, C., & Campbell, L. (1992). Memory accessibility and probability judgments: An experimental evaluation of the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 890–902.

Magnusson, A. (2000). An overview of epidemiological studies on seasonal affective disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 101, 176–184.

Mayer, J. D., Gaschke, Y. N., Braverman, D. L., & Evans, T. W. (1992). Mood-congruent judgment is a general effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 119–132.

Mogg, K., & Bradley, B. P. (1998). A Cognitive-motivational analysis of Anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 809–848.

Murray, K. B., Di Muro, F., Finn, A., & Leczczyc, P. (2010). The effect of weather on consumer spending. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 17, 512–520.

Mutz, M., & Kämpfer, S. (2011). …und nun zum Wetter: Beeinflusst die Wetterlage die Einschätzung von politischen und wirtschaftlichen Sachverhalten? [...and now the weather: Does weather influence the assessment of political and economic issues?] Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 40, 208–226.

Oyane, N. M., Bjelland, I., Pallesen, S., Holsten, F., & Bjorvatn, B. (2008). Seasonality is associated with anxiety and depression: The Hordaland health study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 105, 147–155.

Page, L. A., Hajat, S., & Kovats, R. S. (2007). Relationship between daily suicide counts and temperature in England and Wales. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191, 106–112.

Parker, P. M., & Tavassoli, N. T. (2000). Homeostasis and consumer behavior across cultures. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 17, 33–53.

Pilcher, J. J. (1998). Affective and daily event predictors of life satisfaction in college students. Social Indicators Research, 43, 291–306.

Przuntek, H., & Müller, T. (Eds.). (2005). Das serotonerge System aus neurologischer und psychiatrischer Sicht. Darmstadt: Steinkopff.

Rehdanz, K., & Maddison, D. (2005). Climate and happiness. Ecological Economics, 52, 111–125.

Robinson, M. D. (2004). Personality as performance: Categorization tendencies and their correlates. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 127–129.

Robinson, M. D., & Compton, R. J. (2008). The happy mind in action: The cognitive basis of subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 220–238). New York: Guilford Press.

Rosenthal, N. E., Moul, D. E., Hellekson, C. J., Oren, D. A., Frank, A., Brainard, G. C., et al. (1993). A multicenter study of light visor for seasonal affective disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 8, 151–160.

Rosenthal, N. E., Sack, D. A., Gillin, J. C., Lewy, A. J., Goodwin, F. K., Davenport, Y., et al. (1984). Seasonal affective disorder. A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 41, 72–80.

Schimmack, U. (2008). The structure of subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 97–123). New York: Guilford Press.

Schimmack, U., Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2002a). Life satisfaction is a momentary judgment and a stable personality characteristic: The use of chronically accessible and stable sources. Journal of Personality, 70, 345–384.

Schimmack, U., & Oishi, S. (2005). The influence of chronically and temporarily accessible information on life satisfaction judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 395–406.

Schimmack, U., Radhakrishnan, P., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., & Ahadi, S. (2002b). Culture, personality, and subjective well-being: Integrating process models of life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 582–593.

Schwarz, N. (2011). Feelings-as-information theory. In P. Van Lange, A. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 289–308). New York: Sage.

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (1983). Mood, misattribution, and judgements of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 513–523.

Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1991). Evaluating one’s life: A judgment model of subjective well-being. In F. Strack & M. Argyke (Eds.), Subjective well-being. In interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 27–47). Oxford: Pergamon.

Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1999). Reports of subjective well-being: judgmental processes and their methodological implications. In D. Kahnemann, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 61–84). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Schwarz, N., Strack, F., Kommer, D., & Wagner, D. (1987). Soccer, rooms, and the quality of life: Mood effects on judgments of satisfaction with life in general and with specific life domains. European Journal of Social Psychology, 17, 67–79.

Suh, E., Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Triandis, H. C. (1998). The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgments across cultures: Emotions versus norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 482–493.

Tamir, M., & Robinson, M. D. (2007). The happy spotlight: Positive mood and selective attention to positive information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1124–1136.

Tamir, M., Robinson, M. D., & Solberg, E. C. (2006). You may worry, but can you recognize threats when you see them? Journal of Personality, 74, 1481–1506.

The Economist. (2005). The Economist Intelligence Unit′s quality-of-life index. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/media/pdf/QUALITY_OF_LIFE.pdf.

Tversky, A., & Griffin, D. (1991). Endowment and contrast in judgments of well-being. In F. Strack, M. Argyle, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Subjective well-being (pp. 101–118). Oxford: Pergamon.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). The international scale interval study. In V. Molle & D. Huschka (Eds.), Quality of life in the new millennium advances-in-quality studies, theoriy and research (pp. 45–58). Dordrecht: Springer Press Social Indicator Research Series.

Watson, D. (2000). Mood and temperament. New York: Guilford.

Winkler, D., Willeit, M., Praschak-Rieder, N., Lucht, M. J., Hilger, E., Konstantinidis, A., et al. (2002). Changes of clinical pattern in seasonal affective disorder (SAD) over time in a german-speaking sample. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 252, 54–62.

Yardley, J. K., & Rice, R. W. (1991). The relationship between mood and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 24, 101–111.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

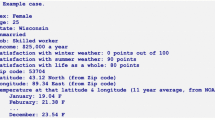

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kämpfer, S., Mutz, M. On the Sunny Side of Life: Sunshine Effects on Life Satisfaction. Soc Indic Res 110, 579–595 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9945-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9945-z