Abstract

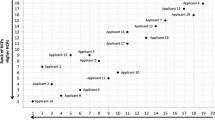

In a replication of the high-profile contribution by Wennerås and Wold on grant peer-review, we investigate new applications processed by the medical research council in Sweden. Introducing a normalisation method for ranking applications that takes into account the differences between committees, we also use a normalisation of bibliometric measures by field. Finally, we perform a regression analysis with interaction effects. Our results indicate that female principal investigators (PIs) receive a bonus of 10% on scores, in relation to their male colleagues. However, male and female PIs having a reviewer affiliation collect an even higher bonus, approximately 15%. Nepotism seems to be a persistent problem in the Swedish grant peer review system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

17 October 2020

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03739-4

References

Asmar, C. (1999), Is there a gendered agenda in academia? The research experience of female and male PhD graduates in Australian universities, Higher Education, 38(3): 255–273.

Black, M. M., Holden, E. W. (1998), The impact of gender on productivity and satisfaction among medical school psychologists, Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 5(1): 117–131.

Bornmann, L., Daniel, H. D. (2005), Selection of research fellowship recipients by committee peer review. Reliability, fairness and predictive validity of Board of Trustees’ decisions, Scientometrics, 63(2): 297–320.

Brouns, M. (2000), The gendered nature of assessment procedures on scientific research funding: the dutch case, Higher Education in Europe, 25: 193–199.

Cole, J. R., Zuckerman, H. (1987), Marriage, Motherhood and Research Performance in Science Scientific American, 256(2): 119.

Gander, J. P. (1999), Faculty gender effects on academic research and teaching, Research in Higher Education, 40(2): 171–184.

Glänzel, W., Debackere, K., Thijs, B., Schubert, A. (2006), A concise review on the role of author self-citations in information science, bibliometrics and science policy, Scientometrics, 67(2): 263–277.

Kulis, S., Sicotte, D., Collins, S. (2002), More than a pipeline problem: Labor supply constraints and gender stratification across academic science disciplines, Research in Higher Education, 43(6): 657–691.

Kyvik, S., Teigen, M. (1996), Child care, research collaboration, and gender differences in scientific productivity, Science Technology & Human Values, 21(1): 54–71.

Levin, S. G., Stephan, P. E. (1998), Gender differences in the rewards to publishing in academe: Science in the 1970s, Sex Roles, 38(11–12): 1049–1064.

Long, J. S. (1992), Measures of sex differences in scientific productivity, Social Forces, 71(1): 159–178.

Moed, H. F. (2005), Citation Analysis in Research Evaluation. Springer Verlag.

Prpic, K. (2002), Gender and productivity differentials in science, Scientometrics, 55(1): 27–58.

Rossiter, M. W. (1993), The Matilda Effect in science, Social Studies of Science, 23: 325–341.

Sandström, U. & pal. (1997), “Does Peer Review Matter?” Peers on Peers. Allocations Policy and Review Procedures at TFR. Stockholm, Swedish Research Council for Engineering Sciences.

van Raan, A. F. J. (2006), Statistical properties of bibliometric indicators: Research group indicator distributions and correlations, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57(3): 408–430.

Wennerås, C., Wold, A. (1997), Nepotism and sexism in peer-review, Nature, 387(6631): 341–343.

Wessely, S. (1998), Peer review of grant applications: what do we know? Lancet, 352(9124): 301–305.

Wold, A., Chrapkowska, C. (2004), Förbjuden frukt på kunskapens träd. Atlantis. [in Swedish]

Xie, Y., Shauman, K. A. (1998), Sex differences in research productivity: New evidence about an old puzzle, American Sociological Review, 63(6): 847–870.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sandström, U., Hällsten, M. Persistent nepotism in peer-review. Scientometrics 74, 175–189 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-008-0211-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-008-0211-3