Abstract

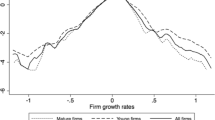

Firms across sectors and regions are highly skewed in their ability to engage with innovation and even more skewed in their ability to translate investments in innovation into higher growth. Recent attention has been placed on the importance of ‘high-growth firms’ (HGF) for innovation policy. Our paper explores under what conditions HGF matter for translating R&D investments into economic growth and how this depends on firm-specific and industry-specific factors. We use quantile regression techniques to study the R&D–growth relationship in HGF compared to low-growth firms. Unlike previous studies, we pay particular attention to whether this relationship depends on the particular period in the industry’s life cycle. We focus on the US pharmaceutical industry from 1963 to 2002 and find that the R&D–growth relationship is sensitive to the changing competitive environment over the industry’s history, which suggests that innovation policy must focus not only on firm attributes but also competitive structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We address our own precise definition and use of the term HGF in Sect. 3.2.

One exception is Falk (2010) whose results indicate R&D intensity had the strongest influence around the median conditional distribution of employment growth for Austrian firms between 1995 and 2006, although fast growers still generally benefit from R&D.

Based on estimates of global pharma sales from IMS (2007).

We make use of both the COMPUSTAT-reported acquisition data and our own analysis of M&A activity to perform robustness checks on our model estimates reported in Sect. 5.

For comparability, we report statistics using the sample applied in our quantile regression model (described in Sect. 4), which includes only those firms with greater than 5 years of consecutive observations. The sample used in the quantile regression analysis is restricted to 1963–2002 because of the unreliability of patent data in the 1950–1962 and 2003–2007 periods, as noted in Sect. 3.1. Regressions run on the 1951–2007 period without including the variable patenting persistence give a similar pattern of results to those described in Sect. 5.

We check our model (reported in Sect. 5) using 3 year logged differenced growth rates and find similar results compared to using the one period measure however because of the lag structure of model used in our estimations it does significantly reduce the sample size, excluding firms with less than 8 years of data. If our analysis is to help reveal the characteristics of all high growth firms and inform policy, it is important to avoid excluding firms, as policy makers cannot know ex-ante which firms will fail.

The six individual measures of R&D have positive loadings of roughly equal size (between 0.28 and 0.5) in the first component.

For firms present in the first year of COMPUSTAT, we manually adjust their age to account for their date of flotation.

R&D scale is strongly correlated with annual R&D expenditure (corr = 0.78); however, rather than investigate the effect of small changes in R&D expenditure on growth, we investigate the extent to which above average annual R&D expenditure has on growth—therefore giving a relative R&D performance measure. R&D scale also has a weak, but negative correlation with R&D intensity.

Note here market is defined as the total annual sales of COMPUSTAT firms.

The HTI (Hall and Tideman 1967), an alternative to the HHI (HHI is calculated as a sum of the squares of market share for each Pharma firm), includes information on the number of firms in the concentration index and takes into account entry.

Here, we are not arguing that there should be a specific date or breakpoint in the competitive regime, but that the pre/post-1980 distinction is a useful method to group the data to capture differences in the competitive environment faced by pharma over time.

See supplementary online material for details.

Similar to Danzon et al. (2007), we look for the effect of M&A on subsequent firm performance, as well as in the acquisition year.

Note, lags of R&D intensity, R&D scale, Sales, VC, and Persist were tested, but were either highly collinear or statistically insignificant and could be dropped without implication to the results reported.

In fact, adjusting this restriction to allow for firms with between a minimum of three (without additional lags in the model) and 10 years of history yields very similar estimation results to those reported in Sect. 5 for R&D intensity and VC.

Regressions run on the 1951–2007 period without patenting persistence give a similar pattern of results for the remaining coefficients to those described in Sect. 5.

Our results for R&D intensity are robust to dropping R&D scale.

See discussion of Schumpeter Mark 1 and Mark 2 in Sect. 2.3.

It is important to note that the presence of VC is much stronger post-1980, although the VC activity present pre-1980 is found to have a statistically significant and positive influence on growth.

If we exclude R&D scale and VC, we find evidence that Persist is statistically significant at growth quantiles above 50 %.

References

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1990). The determinants of small-firm growth in US manufacturing. Applied Economics, 22, 143–153.

Acs, Z. J., Parsons, W., & Spencer, T. (2008). High impact firms: Gazelles revisited. Technical report, Office of Advocacy working paper, US Small Business Administration.

Acs, Z. J., & Yeung, B. (1999). Conclusion. In Z. Acs & B. Yeung (Eds.), Small and medium-sized enterprises in the global economy (pp. 164–173). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Aghion, P., Bloom, N., Blundell, R., Griffith, R., & Howitt, P. (2005). Competition and innovation: An inverted-u relationship. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(2), 701–728.

Almus, M., & Nerlinger, E. A. (1999). Growth of new technology-based firms: Which factors matter?. Small Business Economics, 13(2), 141–154.

Arora, A., & Gambardella, A. (1994). The changing technology of technological change: General and abstract knowledge and the division of innovative labour. Research Policy, 23(5), 523–532.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for inventions. In R. R. Nelson (Ed.), The rate and direction of inventive activity: Economic and social factors. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Audretsch, D. B. (2012). Determinants of high-growth entrepreneurship. OECD/DBA report. http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Audretsch_determinants%20of%20high-growth%20firms.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2013.

Audretsch, D. B., Klomp, L., Santarelli, E., & Thurik, A. R. (2004). Gibrat’s law: Are the services different? Review of Industrial Organization, 24, 301–324.

Barney, J. E. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Baum, J. A. C., & Silverman, B. S. (2004). Picking winners or building them? Alliance, intellectual, and human capital as selection criteria in venture financing and performance of biotechnology start-ups. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 411–436.

Bentzen, J., Madsen, E., & Smith, V. (2012). Do firms’ growth rates depend on firm size? Small Business Economics, 39(4), 937–947.

Bloom, N., & van Reenen, J. (2006). Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries. London: Centre for Economic Performance.

Bottazzi, G., & Secchi, A. (2006). Explaining the distribution of firm growth rates. The Rand Journal of Economics, 37(2), 235–256.

Brouwer, E., Kleinknecht, A., & Reijnen, J. O. N. (1993). Employment growth and innovation at the firm level. Evolutionary Economics, 3, 153–159.

Brown, J. R., Fazzari, S. M., & Petersen, B. C. (2009). Financing innovation and growth: Cash flow, external equity, and the 1990s R&D boom. The Journal of Finance, 64(1), 151–185.

Cefis, E., & Orsenigo, L. (2001). The persistence of innovative activities across-countries and cross-sectors comparative analysis. Research Policy, 30, 1139–1158.

Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Coad, A. (2009). The growth of firms: A survey of theories and empirical evidence. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Coad, A., & Rao, R. (2008). Innovation and firm growth in high-tech sectors: A quantile regression approach. Research Policy, 37, 633–648.

Colombelli, A., Krafft, J., & Quatraro, F. (2012). High growth firms and technological knowledge: Do gazelles follow exploration or exploitation strategies? http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00666707/. Accessed November 1, 2013.

Danzon, P. M., Epstein, A., & Nicholson, S. (2007). Mergers and acquisitions in the pharmaceutical and biotech industries. Managerial and Decision Economics, 28(4–5), 307–328.

Davidsson, P., & Delmar, F. (2006). High-growth firms and their contribution to employment: The case of Sweden. In P. Davidsson, F. Delmar, & J. Wiklund (Eds.), Entrepreneurship and the growth of firms (pp. 156–178). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Davidsson, P., Kirchhoff, B., Hatemi-J, A., & Gustavsson, H. (2002). Empirical analysis of business growth factors using Swedish data. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(4), 332–349

Del Monte, A., & Papagni, E. (2003). R&D and the growth of firms: Empirical analysis of a panel of Italian firms. Research Policy, 32(6), 1003–1014.

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P., & Gartner, W. (2003). Arriving at the high-growth firm. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 189–216.

Demirel, P., & Mazzucato, M. (2012). Innovation and firm growth: Is R&D worth it? Industry and Innovation, 19(1), 45–62.

Dosi, G., & Mazzucato, M. (2006). Knowledge accumulation and industry evolution. The case of pharma-biotech. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ejermo, O., Kander, A., & Henning, M. S. (2011). The R&D–growth paradox arises in fast-growing sectors. Research Policy, 40, 664–672.

European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. http://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2013.

Evans, D. S. (1987). Tests of alternative theories of firm growth. The Journal of Political Economy, 95(4), 657–674.

Falk, M. (2010). Quantile estimates of the impact of R&D intensity on firm performance. Small Business Economics, 39(1), 19–37.

Freel, M., & Robson, P. (2004). Small firm innovation, growth and performance. International Small Business Journal, 22(6), 561–575.

Freeman, C. (1995). The “national system of innovation” in historical perspective. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19(1), 5–24.

Gambardella, A. (1995). Science and innovation in the US pharmaceutical industry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Geroski, P. A., Van Reenen, J., & Walters, C. F. (1997). How persistently do firms innovate? Research Policy, 26(1), 33–48.

Gibrat, R. (1931). Les Inégalités Economiques. Paris: Librairie du Recueil Sirey.

Gompers, P. A., & Lerner, J. (2001). The venture capital revolution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 145–168.

Grabowski, H., & Vernon, J. (1987). Pioneers, imitators, and generics: A simulation model of Schumpeterian competition. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102(3), 491–525.

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hall, B. H. (1987). The relationship between firm size and firm growth in the US manufacturing sector. Journal of Industrial Economics, 35(4), 583–600.

Hall, B. H., Jaffe, A. B., & Trajtenberg, M. (2001). The NBER patent citation data file: Lessons, insights and methodological tools. NBER working papers 8498, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hall, B. H., & Mairesse, J. (1995). Exploring the relationship between R&D and productivity in French manufacturing firms. Journal of Econometrics, 65, 263–293.

Hall B. H., & Oriani, R. (2006). Does the market value R&D investment by European firms? Evidence from a panel of manufacturing firms in France, Germany, and Italy. International Journal of Industrial Organization 24(5), 971–993

Hall, M., & Tideman, N. (1967). Measures of concentration. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 62(317), 162–168.

Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R. S., & Miranda, J. (2013). Who creates jobs? Small versus large versus young. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 347–361.

Hart, P. E., & Oulton, N. (1996). The growth and size of firms. The Economic Journal, 106(3), 1242–1252.

Henrekson, M., & Johansson, D. (2010). Gazelles as job creators: A survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 35, 227–244.

Hölzl, W. (2009). Is the R&D behaviour of fast growing SMEs different? Evidence from CIS III data for 16 countries. Small Business Economics, 33(1), 59–75.

Hymer, S., & Pashigian, P. (1962). Firm size and rate of growth. Journal of Political Economy, 70(6), 556–569.

IMS. (2007). IMS health reports global pharmaceutical market grew 7.0 percent in 2006, to $643 billion. Press release, March 20. http://www.imshealth.com/media. Accessed April 10, 2010.

Kirchhoff, B. A. (1994). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capitalism the economics of business firm formation and growth. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Klepper, S. (1997). Industry life cycles. Industrial and Corporate Change, 6(1), 145–182.

Koenker, R. W. (2004). Quantile regression for longitudinal data. Journal of Multivariate Analysis, 91(1), 74–89.

Koenker, R. W., & Basset, G. J. (1978). Regression quantiles. Econometrica, 46(1), 33–50.

Lang, G. (2009). Measuring the returns of R&D—An empirical study of the German manufacturing sector over 45 years. Research Policy, 38, 1438–1445.

Lechner, C., & Dowling, M. (2003). Firm networks: External relationships as sources for the growth and competitiveness of entrepreneurial firms. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 15, 1–26.

Mansfield, E. (1962). Entry, Gibrat’s law, innovation, and the growth of firms. The American Economic Review, 52(5), 1023–1051.

Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2013). Creating good public policy to support high-growth firms. Small Business Economics, 40, 211–225.

Mazzucato, M. (2000). Firm size, innovation and market structure: The evolution of market concentration and instability. Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Mazzucato, M. (2002). The PC industry: New economy or early life-cycle. Review of Economic Dynamics, 5(2), 318–345.

Mazzucato, M. (2013). The entrepreneurial state: Debunking private vs public sector myths. London: Anthem. ISBN 978-0-85728-252-1.

Mowery, D. C., & Ziedonis, A. A. (2002). Academic patent quality and quantity before and after the Bayh–Dole Act in the United States. Research Policy, 31(3), 399–418.

Nelson, R. (1991). Why do firms differ, and how does it matter? Strategic Management Journal, 12, 61–74.

Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge: Mass Bellknap.

NESTA. (2009). The vital 6 per cent, how high growth innovative businesses generate prosperity and jobs. Research Summary October 2009. http://www.nesta.org.uk/publications/reports/assets/features/the_vital_6_per_cent. Accessed January 17, 2012.

NESTA. (2011). Vital growth. March 2011. http://www.nesta.org.uk/publications/reports/assets/features/vital_growth. Accessed January 17, 2012.

Nightingale, P., & Coad, A. (2014). Muppets and gazelles: Ideological and methodological biases in entrepreneurship research. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(1), 113–143.

OECD. (2010). High-growth enterprises: What governments can do to make a difference, OECD studies on SMEs and entrepreneurship. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Orsenigo, L., Pammolli, F., & Riccaboni, M. (2001). Technological change and network dynamics. Research Policy, 30(3), 485–508.

Paul, S. M., Mytelka, D. S., Dunwiddie, C. T., Persinger, C. C., Munos, B. H., Lindborg, S. R., et al. (2010). How to improve R&D productivity: The pharmaceutical industry’s grand challenge. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 9(3), 203–214.

Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: Oxford University Press.

Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage. New York: Free Press.

Scannell, J. W., Blanckley, A., Boldon, H., & Warrington, B. (2012). Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nature Review of Drug Discovery, 11, 191–200.

Scherer, F. M. (1987). Market structure. Amsterdam: The New Palgrave.

Scherer, F. M., & Ross, D. (1990). Industrial market structure and economic performance. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Schumpeter, J. (1934). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149.

Stam, E., & Wennberg, K. (2009). The roles of R&D in new firm growth. Small Business Economics, 33, 77–89.

Storey, D. J. (1994). Understanding the small business sector. London: Routledge.

Verspagen, B. (2005). Innovation and economic growth. In R. R. Nelson, J. Fagerberg, & D. C. Mowery (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Veugelers, R., & Cincera, M. (2010). Europe’s missing yollies. Bruegel discussion paper. http://www.bruegel.org/publications/publication-detail/publication/430-europes-missing-yollies/. Accessed January 22, 2013.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results was funded by an INET grant on Financing Innovation (INO1200037).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mazzucato, M., Parris, S. High-growth firms in changing competitive environments: the US pharmaceutical industry (1963 to 2002). Small Bus Econ 44, 145–170 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9583-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9583-3

Keywords

- High-growth firms

- Research and development

- Competitive environment

- Quantile regression

- Pharmaceutical industry