Abstract

Private placements provided by institutional or individual accredited investors are becoming an important financing tool for small public firms worldwide. However, private placement issuers offer poor average returns. We explain this puzzle using 2,987 traditional private placements by Canadian small public firms over a decade. We observe significant long-run post-issue underperformance using a classic factor pricing model. This underperformance is partially erased when the returns are adjusted to consider the issuers’ high level of investment, and to include the discount granted to private investors. We split the sample by the glamour/value dimension and by the firms’ investment activity. Only glamour firms with high investment activity underperform in the long run. Private investors obtain positive returns on placements in value and high investment firms. However, they overestimate investment projects of glamour firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The regulator imposes resale restrictions to prevent use of private placements as “backdoor public offerings”, bypassing the more costly public offering that requires a prospectus.

To illustrate this important topic, we can use a stock trading at CAN $10. A PIPE is announced, and the discount is CAN $2 per share. This announcement increases the stock price to CAN $10.50. After that, the stock price decreases to CAN $9. Accordingly, the returns for the investors and the shareholders are respectively 12.5% [(9 − 8)/8] and −14.29% [(9 − 10.5)/10.5]. Why existing shareholders do not integrate the discount in the price and react positively to the announcement of the discounting of a large block of stocks with a negative return expectation is another puzzle offered by PIPEs (Krishnamurthy et al. 2005).

We analyze all private placements registered with the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) involving gross proceeds of CAN $5 million and more, from January 2001 to December 2005. The OSC data allow comprehensive analysis of private investors’ characteristics. These 876 placements constitute the largest Canadian private placements, for which more detailed information is generally available. Only 106 cases of institutional involvement (15.91% of documented cases) were observed. This result is in line with the proportion of 87% of passive (non-institutional investors) reported by Maynes and Pandes (2010).

No adjustments are required to estimate the return of special warrants; they are simply a category of private placement that is convertible into common shares.

According to the average exchange rate of CAN $1.43 for US $1 during the period under analysis, shareholders’ equity of Canadian PIPE issuers is ~25% of that of US issuers.

However, Eckbo et al. (2007, p. 349) reject the hypothesis of non-zero abnormal performance following PIPEs when they use the Carhart model increased by a liquidity factor.

On several occasions, the Financial Post database reports multiple references for a given placement. We carefully analyze each of the issues reported within a 90-day time span, particularly those separated by 1 or 2 days. We consider each of the following placements, reported as distinct in the database, as single issues: two sets of securities, issued within five transaction days, with one being a flow-through; two sets of units placed within a few days and securities placed under the same conditions and at the same price with several investors, within five transaction days. This operation reduces the sample by 396 issues.

The number of observations is higher and their size is smaller than in the previous Canadian paper of Maynes and Pandes (2010) because we include TSXV issuers. Maynes and Pandes restrict their data collection to TSX-listed companies (p. 8). Given that our focus is on small business finance and we partly devote the analysis to high risk companies, we include venture issuers in our sample.

We analyze each case of missing data to track the changes in name, ticker or exchange that might explain the unavailability of data around the issue date. This research was extended to include the case where market data became unavailable several months after an issue. The reasons for the delisting were determined using stock exchange and securities exchange commission bulletins, SEDAR (the Canadian equivalent of the US EDGAR) and several news services. The last reported returns have been adjusted based on the delisting reasons and data, by using zero as the terminal price when the company delisted due to financial problems, and the acquisition price in the case of continuation after a merger or an acquisition. For a company to be included in the analysis, it needed to be able to provide market data for the 3 months before and after the placement date.

In Canada, many PIPEs are issued by firms listed through a reverse merger, a very common transaction that overrides the classical IPO (Carpentier et al. 2011). Such backdoor listing does not allow for the creation of a liquid market for shares, and the market data are not reported. Further, when the PIPE is associated with a reverse merger, market data are not available before the issue, and are generally not available after the PIPE either, because trading can begin only several weeks after the listing. This implies that the missing observations are essentially associated with newly listed firms that use the reverse merger technique.

The European Union (EU) proposes the following limits for medium-sized, small and microenterprises: the total balance sheet should not exceed €43 million, €10 million and €2 million, respectively, in 2003. By converting the first value to Canadian dollars using the exchange rate at the end of 2003, we get a maximum limit of CAN $70 million in 2003. We express this limit in current dollars, using the Canadian consumer price index. Each firm exceeding this limit, adjusted for inflation at the private placement time, is excluded from the sample. The EU definitions are online at: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sme/facts-figures-analysis/sme-definition/index_en.htm.

Consistent with Helwege and Liang (2004), we identify hot and cold issue markets using the 3-month-centered moving averages of the total number of IPOs for each month in the sample. Periods with at least three consecutive months in the upper (lower) third of activity volume constitute the hot (cold) periods. Otherwise, the period is considered neutral. Non-hot issue periods include cold and neutral periods.

Following Carter and Manaster (1990), we consider the most active investment bankers in Canada to be prestigious. During the period under study, seven investment bankers subscribed to 60% of all the initial and seasoned equity issues, and are considered prestigious: RBC Capital Markets, CIBC World Markets Inc., BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc., TD Securities Inc., Scotia Capital Inc., Merrill Lynch Canada Inc. and Goldman, Sachs & Co. No other Canadian-based investment bankers own more than 5% of the total market. We also consider US firms with an assigned rank higher than seven as prestigious. We include in this group international investment bankers such as BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank and UBS based on the list of the most active investment bankers worldwide.

The prestigious auditors are the “Big 5” or the “Big 4”, depending on the year considered.

We favor calendar-time over event-time approaches to analyze the performance of issuing firms during the post-issue periods. Event-time methods suffer from a cross-sectional dependence problem inherent in events that occur in waves and within a wave, or that cluster by industry. This is the case with our sample of Canadian private placements.

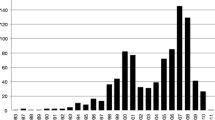

Given that the ordinary least-squares (OLS) procedure is a poor detector of abnormal performance because it averages over months of low and heavy event activity, we use a WLS procedure instead. The weights are proportional to the square root of the number of firms present in each calendar month t such that months with more issues are weighted more heavily. The WLS procedure also deals with potential heteroskedastic residuals induced by calendar clustering (see private equity issue waves in Table 1).

The Canadian stock market includes a venture section, the TSXV, where SMEs are allowed to list at a very early stage of development (Carpentier et al. 2010b). The TSXV describes itself as a public venture market devoted to providing access to capital for earlier-stage companies or smaller financings. The main exchange is the TSX. There were 2,261 issuers listed on the TSXV at November 30, 2008. The average market capitalization was then about CAN $24 million.

In May 1999, the TSX introduced a 10% cap index to avoid the risk of concentration on Nortel Inc., which represented up to 35% of the TSX in September 1999. Almost all Canadian pension plans then adopted the capped index to replace the former non-capped one.

These premiums are slightly higher than those observed by L’Her et al. (2004) over the 1960–2001 period in Canada. They found an average annual market premium of 4.52% and an average annual premium of 5.08% and 5.09% for SMB and HML, respectively. However, while L’Her et al. concentrated on large-cap Canadian companies, we focus on a more representative universe, which is much more small-cap oriented.

See the Chaplinsky and Haushalter (2010) appendix entitled “Estimating the All-in Net Discount and Returns to PIPE Investors”.

We rank private issuers according to book-to-market ratio and partition firms into two groups. We use the median as a breakpoint. We assign a zero to the glamour issuing firms and a one to the value issuing firms. We report the alpha coefficient from each subsample.

References

Baker, M. P., & Wurgler, J. A. (2007). Investor sentiment in the stock market. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 129–151.

Brav, A., Geczy, C., & Gompers, P. A. (2000). Is the abnormal return following equity issuance anomalous? Journal of Financial Economics, 56, 209–249.

Brophy, D. J., Ouimet, P. P., & Sialm, C. (2009). Hedge funds as investors of last resort? Review of Financial Studies, 22(2), 541–574.

Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. The Journal of Finance, 52, 57–82.

Carlson, M., Fisher, A., & Giammarino, R. (2006). Corporate investment and asset price dynamics: Implications for SEO event studies and long-run performance. The Journal of Finance, 61(3), 1009–1034.

Carpentier, C., Cumming, D. J., & Suret, J.-M. (2011). The value of capital market regulation and certification: IPOs versus reverse mergers. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Forthcoming.

Carpentier, C., L’Her, J.-F., & Suret, J.-M. (2010a). Seasoned equity offerings by small and medium sized enterprises, Small Business Economics. doi:10.1007/s11187-010-9271-x.

Carpentier, C., L’Her, J.-F., & Suret, J.-M. (2010b). Stock exchange markets for new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(4), 403–422.

Carpentier, C., & Suret, J.-M. (2010). Private placements by small public entities: Canadian experience. In D. Cumming (Ed.), Private equity: Fund types, risks and returns, and regulation (pp. 129–152). London: Wiley.

Carter, R., & Manaster, S. (1990). Initial public offerings and underwriter reputation. The Journal of Finance, 45(4), 1045–1067.

Chaplinsky, S. J., & Haushalter, D. (2010). Financing under extreme uncertainty: Contract terms and returns to private investments in public equity. Review of Financial Studies, 23(7), 2789–2820.

Chen, H., Dai, N., & Schatzberg, J. D. (2010). The choice of equity selling mechanisms: PIPES versus SEOS. Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(1), 104–119.

Chou, D.-W., Gombola, M., & Liu, F.-Y. (2009). Long-run underperformance following private equity placements: The role of growth opportunities. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 49(3), 1113–1128.

Cochrane, J. H. (1991). Production-based asset pricing and the link between stock returns and economic fluctuations. The Journal of Finance, 46(1), 209–237.

Cochrane, J. H. (1996). A cross-sectional test of an investment-based asset pricing. Journal of Political Economy, 104(3), 572.

Cooper, M. J., Gulen, H., & Schill, M. J. (2008). Asset growth and the cross-section of stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 63(4), 1609–1651.

Dai, N. (2010). The rise of the PIPE market. In D. Cumming (Ed.), Private equity: Fund types, risks and returns, and regulation (pp. 111–127). London: Wiley.

Eckbo, E., Masulis, R. W., & Norli, O. (2000). Seasoned public offerings: Resolution of the ‘new issues puzzle’. Journal of Financial Economics, 56(2), 251–291.

Eckbo, B., Masulis, R., & Norli, O. (2007). Security offerings: A survey. In B. Eckbo (Ed.), Handbook of corporate finance: Empirical corporate finance, vol. 1 (pp. 233–373). North-Holland: Elsevier.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3–56.

Gombola, M. J., Lee, H. W., & Liu, F.-Y. (1999). Further evidence on insider selling prior to seasoned equity offering announcements: The role of growth opportunities. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 26(5/6), 621–650.

Graham, J. R., & Harvey, C. R. (2001). Theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. Journal of Financial Economics, 60, 187–243.

Haggard, S. K., Zhang, Y. J., & Ma, T. (2009). PIPEs around the world. Journal of Private Equity, 12(4), 57–68.

Helwege, J., & Liang, N. (2004). Initial public offerings in hot and cold markets. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 39(3), 541–569.

Hertzel, M., Lemmon, M., Link, J. S., & Rees, L. (2002). Long-run performance following private placements of equity. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2595–2617.

Hertzel, M., & Smith, R. L. (1993). Market discounts and shareholder gains for placing equity privately. The Journal of Finance, 48, 459–485.

Hoechle, D. & Schmid, M. M. (2009). Predicting and explaining IPO underperformance. Retrieved February 24, 2009 http://ssrn.com/abstract=1014011.

Huson, M. R., Malatesta, P. H., & Parrino R. (2009). Capital market conditions and the pricing of private equity sales by public firms. Working paper. Retrieved May 23, 2010 from http://www.mccombs.utexas.edu/faculty/robert.parrino/HMP%202.pdf.

Huson, M., Malatesta, P. H. & Parrino, R. (2010). The decline in the cost of private placements working paper. Retrieved May 23, 2010 from http://www.mccombs.utexas.edu/faculty/robert.parrino/HMP%202.pdf.

Krishnamurthy, S., Spindt, P., Subramaniam, V., & Woidtke, T. (2005). Does investor identity matter in equity issues? Evidence from private placements. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 14(2), 210–238.

Kumar, A. (2009). Hard-to-value stocks, behavioral biases, and informed trading. Journal of Financial & Quantitative Analysis, 44(6), 1375–1401.

L’Her, J.-F., Masmoudy, T., & Suret, J.-M. (2004). Evidence to support the four-factor pricing model from the Canadian stock market. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 14(4), 1–16.

Loughran, T., & Ritter, J. R. (2000). Uniformly least powerful tests of market efficiency. Journal of Financial Economics, 55(3), 361–389.

Lyandres, E., Sun, L., & Zhang, L. (2008). The new issues puzzle: Testing the investment-based explanation. Review of Financial Studies, 21(6), 2825–2855.

Marciukaityte, D., Szewczyk, S. H., & Varma, R. (2005). Investor overoptimism and private equity placements. Journal of Financial Research, 28(4), 591–605.

Maynes, E. & Pandes, J. A. (2010). The wealth effects of reducing private placement resale restrictions. European Financial Management, 17, 500–531.

Wruck, K. H., & Wu, Y. (1989). Relationships, corporate governance, and performance: Evidence from private placements of common stock. Journal of Financial Economics, 23, 3–21.

Wu, Y. (2004). The choice of equity-selling mechanisms. Journal of Financial Economics, 74, 93–119.

Acknowledgement

Jean-Marc Suret and Cécile Carpentier gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and from the Autorité des marchés financiers du Québec. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Canadian Pension Plan or of the Autorité des marchés financiers du Québec.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carpentier, C., L’Her, JF. & Suret, JM. Private investment in small public entities. Small Bus Econ 41, 149–168 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9407-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9407-7

Keywords

- Private investment in public equity

- Financing decision

- Private equity

- Small business finance

- Long-run performance