Abstract

This study empirically investigates the association between institutional ownership composition and accounting conservatism. Transient (dedicated) institutional investors, holding diversified (concentrated) portfolios with high (low) portfolio turnover, focus on portfolio firms’ short-term (long-term) perspectives and trade heavily (generally do not trade) on current earnings news. Thus, I predict that as transient (dedicated) institutional ownership increases, firms will exhibit a lower (higher) degree of accounting conservatism. Consistent with my predictions, in the context of asymmetric timeliness of earnings, I document that as the level of transient (dedicated) institutional ownership increases, earnings become less (more) asymmetrically timely in recognizing bad news.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

PEAD refers to the tendency for abnormal returns to drift following earnings announcements in the direction of earnings surprises.

Chen et al. (2007) refine their monitoring measure by intersecting groups of independent long-term institutions with those identified by Bushee’s method as dedicated and quasi-indexer investors. Their results remain unchanged, when they intersect only the dedicated institution sample with the sample of independent long-term institutions with concentrated ownership.

Following Beaver and Ryan (2005), I refer to this news-dependent conservatism as conditional conservatism. Unconditional or news-independent conservatism refers to the understatement of stockholders’ equity as a result of historical accounting and under-recognition of certain assets (Feltham and Ohlson 1995). In this paper, I only focus on conditional conservatism as it plays a clear role in the monitoring functions of corporate governance, of which dedicated institutional investors are a key component. Moreover, conditional conservatism is more suitable than unconditional conservatism when it comes to testing the relation between transient institutional ownership and accounting conservatism, as transient investors’ trading behavior is most sensitive to current earnings news, i.e., news-dependent.

LaFond and Roychowdhury (2008) use the Fama–MacBeth procedure when examining the effect of managerial ownership on financial reporting conservatism, proxied by asymmetric timeliness of earnings; LaFond and Watts (2008) also use the same procedure to investigate the relation between information asymmetry and asymmetric timeliness of earnings; and Huijgen and Lubberink (2005) use the same method to compare asymmetric timeliness of earnings of U.K. companies cross-listed in the U.S. to that of U.K. companies without a U.S.-listing.

Ball and Shivakumar (2005) argue that it is difficult to infer how contracting is affected by unconditional conservatism. If the amount of an unconditional accounting bias is known, rational agents would simply account for the bias. If the bias is unknown, it can only bring noise in financial information and can only decrease contracting efficiency.

For example, Ball and Shivakumar (2005) hypothesize that private company financial reporting is of lower quality due to different market demand. Tests conducted in a large U.K. sample support this hypothesis, in which quality is measured using Basu’s (1997) measure of timely loss recognition and an accruals-based method.

For example, Bushman and Piotroski (2006) analyze relations between key characteristics of country-level institutions and conditional conservatism. They find that firms in countries with high quality judicial systems incorporate bad news in earnings faster than firms in countries with low quality judicial systems.

For example, Wittenberg-Moerman (2008) documents that timely loss recognition reduces the bid-ask spread in the secondary-loan market, which follows that conservative reporting reduces information asymmetry pertaining to a borrower.

For example, Lafond and Roychowdhury (2008) study the effect of managerial ownership on financial reporting conservatism and document a negative association between managerial ownership and asymmetric timeliness of earnings.

Ball and Shivakumar (2005) measure conditional conservatism based on the relation between accruals and cash flows. They argue that the negative relation between earnings and operating cash flows is less pronounced in bad news periods as a result of the asymmetric recognition criteria for losses and gains. Losses are likely to be recorded on a timely basis through unrealized accruals, while gains are recorded when realized and thus recognized on a cash basis.

Givoly and Hayn (2000) measure conservatism based on the accumulation of operating accruals. They find that higher accounting conservatism gives rise to larger negative total accruals. Notice that negative total accruals is a measure of total conservatism, rather than conditional conservatism. García Lara et al. (2009) acknowledge that this measure captures conditional conservatism with some noise.

Mutual funds are included in the Investment Advisor classifications. Generally, mutual funds also manage pension investments on behalf of their clients and are classified on the 13-F as Investent Advisors.

Due to a mapping error, CDA/Spectrum’s type classification is not accurate beyond 1998. Many institutions are inappropriately labeled as Type 5 institutions (all others) (Chen et al. 2007).

The fourth category characterized by concentrated portfolios with high turnover does not exist. Due to transaction costs and liquidity issues, it would be impossible to run a trading strategy that makes highly-frequent trades in large blocks of stock. I thank Professor Brian Bushee for his clarification on this category.

An alternate explanation for managers trying to avoid missing analyst forecasts is offered by Mergenthaler et al. (2009). They find that missing the quarterly analyst earnings forecast results in career penalties, for example, a smaller bonus, decreased equity grants, and a higher possibility of displacement for both CEOs and CFOs.

Momentum investors are determined by studying the stocks purchased, held and sold by each fund manager over six consecutive quarters. Momentum investors exhibit the greatest inclination to buy (sell) stocks with positive (negative) analyst revisions. Momentum investors classified by Georgeson & Co. are similar to transient institutional investors under Bushee’s classification. For example, only 2.9 % of momentum investors are identified to have low turnover (Hotchkiss and Strickland 2003, p. 1477).

Notice that when developing the relation between transient ownership and accounting conservatism, I do not focus on corporate governance. The rational is as follows, as transient investors, by definition, hold stocks for short periods of time, therefore, they have fewer incentives to invest in monitoring and thus influence corporate governance.

I thank Professor Brian Bushee for providing access to the institutional investor classifications used throughout this study.

Bushee (1998) argues that the manager likely has an accurate estimate of annual earnings and starts to consider myopic investment decisions in the middle of the second half of the fiscal year; therefore institutional ownership is measured at the end of firms’ third fiscal quarter.

See http://www.sec.gov/divisions/investment/13ffaq.htm for more information.

The Tobit Model is adopted in the context of asset write-downs, as this model has been adopted in the prior research. For example, Francis et al. (1996) use a Tobit estimation procedure to test the causes and effects of discretionary asset write-offs; Riedl (2004) uses a Tobit model to carry out an examination of long-lived asset write-downs; and Chao and Horng (2013) also use Tobit regressions to carry out tests relating to asset write-offs. The Tobit model is assuming the data is censored. In the context of asset write-downs, the assumed latent variable is the change in the value of the firm’s asset, which can lead to an asset write-down or a write-up. However, U.S. GAAP does not generally allow reporting of asset write-ups, and thus these unobservable (non-reported) asset write-ups make up that portion of the distribution of the censored dependent variable, which the Tobit specification aims to fill in (Riedl 2004). Therefore, in this paper, the dependent variable is left censored at zero.

Specifically, data item 380 (write-downs pretax) is the sum of all write-down special items reported before taxes, which includes impairment of assets other than goodwill and write-down of assets other than goodwill.

Some researchers (e.g., Francis et al. 1996) include a firm’s stock return as an explanatory variable for asset write-downs. However, researchers also document that asset write-downs are an input used by stock market investors to determine firm value (e.g., Elliott and Hanna 1996), which suggests that market-based measures would be endogenous if included as explanatory variables. Meanwhile, researchers find that a firm’s stock decline precedes write-off announcements (e.g., Francis et al. 1996), that the stock market reacts negatively to announcements of asset write-downs (e.g., Bunsis 1997), and that abnormal returns of firms reporting write-offs continue to decline after the announcement by as much as 21 % annually for a two-year period (Bartov et al. 1998). Therefore, a market-based proxy for bad news is susceptible to the confounding time effect before, at the same time as, and after the announcement of asset write-downs. Accordingly, I use accounting-based measures as proxies for bad news.

BATH equals the change in pre-write-off earnings from t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1, when this change is below the median of nonzero negative values, and zero otherwise. SMOOTH equals the change in pre-write-off earnings from t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1, when this change is above the median of nonzero positive values, and zero otherwise. In line with firms taking a “big bath,” I predict a negative correlation between write-downs and BATH. In line with firms engaging in income smoothing, I predict a positive correlation between write-offs and SMOOTH.

In the subsample analysis, dummy variable DUM_SALES and its related interaction terms are left out from Eq. (3), as the subsample consists of firms experiencing greater than the median value of sales declines (−8.6 %).

References

Ahmed AS, Duellman S (2007) Accounting conservatism and board of director characteristics: an empirical analysis. J Account Econ 43(2/3):411–437

Ali A, Klasa S, Li OZ (2008) Institutional stakeholdings and better-informed traders at earnings announcements. J Account Econ 46(1):47–61

Ball R, Shivakumar L (2005) Earnings quality in U.K. private firms: comparative loss recognition timeliness. J Account Econ 39(1):83–128

Bartov E, Lindahl FW, Ricks WE (1998) Stock price behavior around announcements of write-offs. Rev Account Stud 3(4):327–346

Basu S (1997) The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. J Account Econ 24(1):3–37

Beaver WH, Ryan SG (2005) Conditional and unconditional conservatism: concepts and modeling. Rev Account Stud 10(2/3):269–309

Beekes W, Pope P, Young S (2004) The link between earnings timeliness, earnings conservatism and board composition: evidence from the UK. Corp Gov Int Rev 12(1):47–59

Brown K, Brooke B (1993) Institutional demand and security price pressure: the case of corporate spin-offs. Financ Anal J 49(5):53–62

Bunsis H (1997) A description and market analysis of write-off announcements. J Bus Financ Account 24(9/10):1385–1400

Bushee BJ (1998) The influence of institutional investors on myopic R&D investment behavior. Account Rev 73(3):305–333

Bushee BJ (2001) Do institutional investors prefer near-term earnings over long-run value? Contemp Account Res 18(2):207–246

Bushman RM, Piotroski JD (2006) Financial incentives for conservative accounting: the influence of legal and political institutions. J Account Econ 42(1/2):107–148

Chao CL, Horng SM (2013) Asset write-offs discretion and accruals management in Taiwan: the role of corporate governance. Rev Quant Financ Account 40(1):41–74

Chen X, Harford J, Li K (2007) Monitoring: which institutions matter? J Financ Econ 86(2):279–305

Dikolli SS, Kulp SL, Sedatole KL (2009) Transient institutional ownership and CEO contracting. Accont Rev 84(3):737–770

Dong M, Ozkan A (2008) Institutional investors and director pay: an empirical study of UK companies. J Multi Financ Manag 18(1):16–29

Elliott J, Hanna J (1996) Repeated accounting write-offs and the information content of earnings. J Account Res 34(Supplement):135–155

Fama E, MacBeth J (1973) Risk, return, and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Polit Econ 81(3):607–636

Feltham GA, Ohlson JA (1995) Valuation and clean surplus accounting for operating and financial activities. Contemp Account Res 11(2):689–731

Ferri F, Sandino T (2009) The impact of shareholder activism on financial reporting and compensation: the case of employee stock options expensing. Account Rev 84(2):433–466

Francis J, Hanna J, Vincent L (1996) Causes and effects of discretionary asset write-offs. J Account Res 34(supplement):117–134

García Lara JM, García Osma B, Penalva F (2009) Accounting conservatism and corporate governance. Rev Account Stud 14(1):161–201

Givoly D, Hayn C (2000) The changing time-series properties of earnings, cash flows and accruals: has financial reporting become more conservative? J Account Econ 29(3):287–320

Gompers P, Ishii J, Metrick A (2003) Corporate governance and equity prices. Q J Econ 118(1):107–155

Hotchkiss ES, Strickland D (2003) Does shareholder composition matter? Evidence from the market reaction to corporate earnings announcements. J Financ 58(4):1469–1498

Huijgen C, Lubberink M (2005) Earnings conservatism, litigation and contracting: the case of cross-listed firms. J Bus Financ Account 32(7/8):1275–1309

Kahan M, Rock EB (2007) Hedge funds in corporate governance and corporate control. Univ Penn Law Rev 155(5):1021–1093

Ke B, Ramalingegowda S (2005) Do institutional investors exploit the post-earnings announcement drift? J Account Econ 39(1):25–53

Koh PS (2007) Institutional investor type, earnings management and benchmark beaters. J Account Public Policy 26(3):267–299

Kwon SS, Yin QJ, Han J (2006) The effect of differential accounting conservatism on the “over-valuation” of high-tech firms relative to low-tech firms. Rev Quant Financ Account 27(2):143–173

LaFond R, Roychowdhury S (2008) Managerial ownership and accounting conservatism. J Account Res 46(1):101–135

LaFond R, Watts RL (2008) The information role of conservatism. Account Rev 83(2):447–478

Lin L, Manowan P (2012) Institutional ownership composition and earnings management. Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Polic 15(4). doi:10.1142/S0219091512500221

Matsumoto DA (2002) Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises. Account Rev 77(3):483–514

Mergenthaler RD, Rajgopal S, Srinivasan S (2009) CEO and CFO career penalties to missing quarterly analysts forecasts. Working Paper, Harvard Business School

Porter M (1992) Capital choices: changing the way America invests in industry. Council on Competitiveness, Harvard Business School, Boston

Riedl EJ (2004) An examination of long-lived asset impairments. Account Rev 79(3):823–852

Roychowdhury S, Watts RL (2007) Asymmetric timeliness of earnings, market-to-book and conservatism in financial reporting. J Account Econ 44(1/2):2–31

Watts RL (2003a) Conservatism in accounting. Part I. Explanations and implications. Account Horiz 17(3):207–221

Watts RL (2003b) Conservatism in accounting. Part II. Evidence and research opportunities. Account Horiz 17(4):287–301

Watts RL, Zimmerman JL (1978) Toward a positive theory of the determination of accounting standards. Account Rev 53(1):112–134

Wittenberg-Moerman R (2008) The role of information asymmetry and financial reporting quality in debt trading: evidence from the secondary loan market. J Account Econ 46(2/3):240–260

Zheng Y (2010) Heterogeneous institutional investors and CEO compensation. Rev Quant Financ Account 35(1):21–46

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on my dissertation at Boston University. I thank my dissertation chairman, Professor Krishnagopal Menon, for his continuous guidance in the development of this paper. I also thank other members of my dissertation committee—Professor Kumar Sivakumar and Professor Jacob Oded—as well as Professor Brian Bushee for providing access to the institutional investor classifications used throughout this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Variable definitions

TRA | ≡ | percentage of shares outstanding held by transient institutional investors per Bushee (1998) |

TRA_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of TRA a |

DED | ≡ | percentage of shares outstanding held by dedicated institutional investors per Bushee (1998) |

DED_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of DED |

QIX | ≡ | percentage of shares outstanding held by quasi-indexers per Bushee (1998) |

QIX_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of QIX |

WOTA | ≡ | firm i’s reported pre-tax long-lived asset write-off (computed as a positive amount) for period t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1 |

∆GDP | ≡ | the percentage change in U.S. Gross Domestic Product from period t − 1 to t |

∆SALES | ≡ | the percent change in sales for firm i from period t − 1 to t |

∆E_p | ≡ | the change in firm i’s pre-write-off earnings from period t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1 |

FRET | ≡ | firm’s stock return, measured over firm’s fiscal year t |

DUM_SALES | ≡ | equal to one if a firm experiences a sales decline during the year t, and zero otherwise |

DUM_∆E_p | ≡ | equal to one if a firm experiences a decline in its pre-write-off earnings during the year t, and zero otherwise |

NI | ≡ | net income before extraordinary items divided by beginning of fiscal year market value of equity |

RET | ≡ | buy-and-hold return by compounding 12 monthly CRSP stock returns ending three months after fiscal year-end |

NEG | ≡ | equal to one if RET is negative, and zero otherwise |

MB | ≡ | market-to-book ratio at the beginning of the fiscal year |

MB_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of MB |

LEV | ≡ | total debt divided by total assets at the beginning of the fiscal year |

LEV_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of LEV |

SIZE | ≡ | the natural logarithm of market value of equity at the beginning of the fiscal year |

SIZE_r | ≡ | the scaled decile rank of SIZE |

LIT | ≡ | equal to one if a firm is in a litigious industry—SIC codes 2833–2836, 3570–3577, 3600–3674, 5200–5961, and 7370–7374, and zero otherwise |

BATH | ≡ | equal to the change in pre-write-off earnings from t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1, when this change is below the median of nonzero negative values, and zero otherwise |

SMOOTH | ≡ | equal to the change in pre-write-off earnings from t − 1 to t, divided by total assets at the end of t − 1, when this change is above the median of nonzero positive values, and zero otherwise |

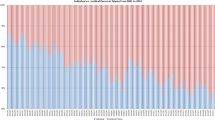

Appendix 2: Spectrum type by Bushee’s classification

Spectrum type | Bushee’s classification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

DED | QIX | TRA | Total | Percent | ||

1 | Bank | 563 | 4,373 | 608 | 5,544 | 15.1 |

2 | INS | 221 | 1,232 | 448 | 1,901 | 5.2 |

3 | INV | 131 | 937 | 456 | 1,524 | 4.2 |

4 | IIA | 1,442 | 13,532 | 9,119 | 24,093 | 65.7 |

5 | CPS | 136 | 640 | 181 | 957 | 2.6 |

5 | PPS | 9 | 358 | 47 | 414 | 1.1 |

5 | UFE | 44 | 281 | 73 | 398 | 1.1 |

5 | MSC | 121 | 1,052 | 672 | 1,845 | 5.0 |

Total | 2,667 | 22,405 | 11,604 | 36,676 | 100 | |

Percent | 7.3 | 61.1 | 31.6 | 100 | ||

Spectrum’s type

-

BNK = bank trust (Spectrum type code 1)

-

INS = insurance company (2)

-

INV = investment company (3)

-

IIA = independent investment advisor (4)

-

CPS = corporate (private) pension fund (5)

-

PPS = public pension fund (5)

-

UFE = university and foundation endowments (5)

-

MSC = miscellaneous (5)

Bushee’s classification

-

DED = dedicated institutional investors per Bushee (1998)

-

QIX = quasi-indexers per Bushee (1998)

-

TRA = transient institutional investors per Bushee (1998)

-

Source: http://accounting.wharton.upenn.edu/faculty/bushee/iiclass/desctdqxtc.txt.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, L. Institutional ownership composition and accounting conservatism. Rev Quant Finan Acc 46, 359–385 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-014-0472-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-014-0472-2