Abstract

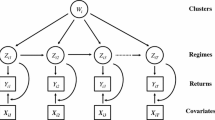

Recent studies show that regression-based estimates of accounting conservatism reflect both differences in the asymmetric recognition of bad news and differences in asset composition. In particular, a firm’s market value and returns reflect both assets-in-place and expected future rents, while book values tend to reflect only assets-in-place. We propose two tests that remove the effect of asset composition on cross-sectional comparisons of accounting conservatism. First, a test based on a ratio of regression coefficients allows for valid cross-sectional comparisons of conservatism relative to overall news recognition. Second, in some cases, researchers can separately identify and make cross-sectional comparisons of the fraction of good news recognized and the fraction of bad news recognized. The estimates in this second scenario use a regression of earnings on returns interacted with a book-to-market ratio. We validate our model by deriving and testing several predictions based on it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Guay and Verrecchia (2006) for a discussion of the importance of distinguishing between estimates of a firm’s bad news recognition versus its recognition of bad news relative to good news.

See the contemporaneous paper by Ball et al. (2009) for an alternative econometric model.

We searched articles in Contemporary Accounting Research, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Journal of Accounting Research, Review of Accounting Studies, and The Accounting Review through March 2012.

We show that controlling for lagged earnings yields statistically significant coefficients on positive earnings in earnings/returns regressions, which is important for using a ratio to infer conservatism.

Although not modeled here, current earnings could also recognize a portion of prior unrecognized changes in separable assets and realized rents. The exclusion of these elements from the model does not affect our inferences because we assume the current recognition of prior returns is uncorrelated with current returns. Our more elaborate econometric model available from the authors does incorporate these additional elements.

This does not eliminate the need to have a fairly precise measure of the coefficient on positive returns. The Appendix discusses the Fieller method procedure for computing confidence intervals for ratios of regression coefficients. The regression coefficients must be statistically significant in order to have bounded confidence intervals. For example, a 95 % confidence interval requires that the regression coefficients be significant at the 5 % level. This implies that the ratios will be statistically insignificant in settings where the asymmetric timeliness coefficient is statistically insignificant, such as Eng and Lin (2012) examination of Chinese cross-listing firms.

Although this prediction is not immediately obvious, the derivation is available from the authors upon request.

The market-to-book ratio reflects both asymmetric timeliness and ex ante conservatism.

Our analysis in the next section shows that the typical Basu (1997) framework produces estimates of β 2 near zero. However, including additional controls to better measure unexpected earnings and unexpected returns often results in a positive coefficient on positive returns.

Pope and Walker (1999) do not assess the statistical significance of their ratio measures.

We use earnings per share from continuing operations, but note there is no consistency in the literature. Of the 36 studies that use returns in their measurement of conservatism, 18 use earnings per share from continuing operations, 10 use earnings per share, 4 use both, and 4 do not provide enough detail to determine which measure they used.

This evidence must be viewed as consistent with P2, but not as conclusive. This is because multiplying returns by any number between zero and one will tend to generate larger coefficients. The interpretation of the estimates rests on their derivation from our econometric model. If the book-to-market ratio is unrelated to the structural construct λ, then its interaction with returns when estimating (7) can be viewed as a source of bias. For the specification to be totally invalid would require the book-to-market ratio to be totally unrelated to the portion of firm value due to separable net assets, which seems unlikely; however, the book-to-market ratio is an imperfect measure of λ and therefore does yield some estimation bias as we noted earlier.

The difference in coefficient results relative to Kwon et al. (2006) may be due to differences in sample construction.

The number of observations is reduced in these tests due to the variable restrictions necessary to estimate the Shu (2000) model.

Untabulated analysis shows that the mean (median) beginning book-to-market ratio of high litigation firms is 0.560 (0.447) versus 0.781 (0.626) for the non-high litigation firms.

We also recognize that economic circumstances affect the implementation of standards and cause variation in conservatism measures across time. Our model explicitly allows this. However, as Givoly et al. (2007) point out, the variation across time may partially be due to poor estimation in years with few negative news observations.

The market-to-book ratio is also impacted by ex ante conservatism since ex ante conservatism excludes rents from book values and can also understate separable assets via, for example, accelerated depreciation.

For the AT coefficients, discretionary accruals, and the persistence coefficient the null to test significance is zero. For the ratios and book-to-market the null to test significance is one, and for the CR rank significance is tested relative to a null of three.

Also see Staiger, Stock and Watson (1997) for an example application of this approach.

If d′β < 0 the second inequality is reversed, but (A2) still determines the confidence interval.

For example, if the ratio’s denominator is the jth regressor β j , then \( a_{2} = (\varvec{\beta}_{j}^{2} /\hat{\varvec{\sigma }}_{jj}^{2} - t_{\alpha /2}^{2} )\hat{\varvec{\sigma }}_{jj}^{2} \) so that \( a_{2} < 0 \)and the confidence interval is unbounded if β j is insignificant based on a two-tailed test with significance α.

We computed the confidence intervals using the regFieller.ado Stata program available on Judson Caskey’s website: http://webspace.utexas.edu/jc2279/www/data.html.

References

Ahmed A, Billings B, Morton R, Stanford-Harris M (2002) The role of accounting conservatism in mitigating bondholder‐shareholder conflicts over dividend policy and in reducing debt costs. Acc Rev 77(4):867–890

Ball R, Shivakumar L (2005) Earnings quality in UK private firms: comparative loss recognition timeliness. J Acc Econ 39(1):83–128

Ball R, Kothari S, Nikolaev V (2009) Econometrics of the Basu asymmetric timeliness coefficient and accounting conservatism. University of Chicago and MIT, Working paper

Barth M, Landsman W, Lang M (2008) International accounting standards and accounting quality. J Acc Res 46(3):467–498

Basu S (1977) Investment performance of common stocks in relation to their price-earnings ratios: a test of the efficient market hypothesis. J Financ 32(3):663–682

Basu S (1997) The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. J Acc Econ 24(1):3–37

Basu S (1999) Discussion of International differences in the timeliness, conservatism, and classification of earnings. J Acc Res 37:89–99

Beatty A (2007) Discussion of ‘Asymmetric timeliness of earnings, market-to-book and conservatism in financial reporting’. J Acc Econ 44(1–2):32–35

Beaver W, Ryan S (2000) Biases and lags in book value and their effects on the ability of the book-to-market ratio to predict return on equity. J Acc Res 38(1):127–148

Brauer S, Westermann F (2012) On the time series measure of conservatism: a threshold autoregressive model. Rev Quant, Finance Account (Forthcoming)

Buonaccorsi J (1979) Letters to the editor. Am Stat 33(3):162

Callen J, Hope O, Segal D (2010) The pricing of conservative accounting and the measurement of conservatism at the firm-year level. Rev Acc Stud 15:145–178

Chandra U, Wasley C, Waymire G (2004) Income conservatism in the U.S. technology sector. Working paper, University of Kentucky, University of Rochester and Emory University

Dietrich J, Muller K, Riedl E (2007) Asymmetric timeliness tests of accounting conservatism. Rev Acc Stud 12(1):95–125

Easton P, Pae J (2004) Accounting conservatism and the relation between returns and accounting data. Rev Acc Stud 9(4):495–521

Elbannan M (2011) Accounting and stock market effects of international accounting standards adoption in an emerging economy. Rev Quant Financ Acc 36(2):207–245

Eng L, Lin Y (2012) Accounting quality, earnings management and cross-listings: evidence from China. Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Policies 15(2):1250009

Ettredge M, Huang Y, Zhang W (2012) Earnings restatements and differential timeliness of accounting conservatism. J Acc Econ 53:489–503

Fama E, French K (1992) The cross-section of expected stock returns. J Financ 47(2):427–465

Fama E, French K (1997) Industry costs of equity. J Financ Econ 43(2):153–193

Fieller E (1954) Some problems in interval estimation. J R Stat Soc B Met 16(2):175–185

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (1975) Accounting for contingencies. Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 5. FASB, Norwalk, CT

Francis J, Schipper K (1999) Have financial statements lost their relevance? J Acc Res 37(2):319–352

Givoly D, Hayn C (2000) The changing time-series properties of earnings, cash flows and accruals: has financial reporting become more conservative? J Acc Econ 29(3):287–320

Givoly D, Hayn C, Natarajan A (2007) Measuring reporting conservatism. Acc Rev 82(1):65–106

Guay W, Verrecchia R (2006) Discussion of an economic framework for conservative accounting and Bushman and Piotroski (2006). J Acc Econ 42(1–2):149–165

Khan M, Watts R (2009) Estimation and empirical properties of a firm-year measure of accounting conservatism. J Acc Econ 48:132–150

Krishnan G, Visvanathan G (2008) Does the SOX definition of an accounting expert matter? The association between audit committee directors’ accounting expertise and accounting conservatism. Contemp Acc Res 25(3):827–857

Kwon S, Yin Q, Han J (2006) The effect of differential accounting conservatism on the “over-valuation” of high-tech firms relative to low-tech firms. Rev Quant Financ Acc 27:143–173

Pae J, Thornton D, Welker M (2005) The link between earnings conservatism and the price-to-book ratio. Contemp Acc Res 22(3):693–717

Patatoukas P, Thomas J (2009) Revisiting the Basu (1997) estimate of conditional conservatism. Yale University, Working paper

Penman S, Zhang X (2002) Accounting conservatism, the quality of earnings, and stock returns. Acc Rev 77(2):237–264

Pope P, Walker M (1999) International differences in the timeliness, conservatism, and classification of earnings. J Acc Res 37:53–87

Roychowdhury S, Watts R (2007) Asymmetric timeliness of earnings, market-to-book and conservatism in financial reporting. J Acc Econ 44(1–2):2–31

Ryan S, Zarowin P (2003) Why has the contemporaneous linear returns-earnings relation declined? Acc Rev 78(2):523–553

Shu S (2000) Auditor resignations: clientele effects and legal liability. J Acc Econ 29:173–205

Staiger D, Stock J, Watson M (1997) The NAIRU, unemployment and monetary policy. J Econ Perspect 11(1):33–49

Vuolteenaho T (2002) What drives firm-level stock returns. J Financ 57(1):233–264

Wang D (2006) Founding family ownership and earnings quality. J Acc Res 44(3):619–656

Watts R (2003a) Conservatism in accounting part I: explanations and implications. Acc Horiz 17(3):207–221

Watts R (2003b) Conservatism in accounting part II: evidence and research opportunities. Acc Horiz 17(4):287–301

Zerbe G (1978) On Fieller’s theorem and the general linear model. Am Stat 32(3):103–105

Acknowledgments

We thank an anonymous referee, David Aboody, Sudipta Basu, Peter Demerjian, Carla Hayn, Jack Hughes, Steve Matsunaga, Karl Muller, Eddie Riedl and workshop participants at AAA FARS 2009 Mid-Year Meeeting, Pennsylvania State University, UCLA and University of Southern California for their helpful comments. This paper was previously titled “On the estimation of the asymmetric timeliness of earnings: Inference and bias corrections.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

This appendix describes the construction of confidence intervals for ratios of regression coefficients based on Fieller’s Theorem (Fieller 1954) as implemented in Zerbe (1978).Footnote 22 The confidence intervals are based on transforming a hypothesis for the ratio to an equivalent linear hypothesis. Given a value k, a vector β of p estimated coefficients and vectors n and d, the ratio \( \varvec{n}^{\prime } \varvec{\beta /d}^{\prime } \varvec{\beta > k} \) if and only if \( \varvec{n}^{\prime }\varvec{\beta}/\varvec{kd}^{\prime }\varvec{\beta}> 0 \).Footnote 23 Given estimated coefficients \( \hat{\varvec{\beta }} \) and covariance matrix \( \hat{\varvec{\Upsigma }} \) , a t-statistic for the inequality is:

Given a confidence level α, sample size N and critical t-statistic t α/2 with N − p degrees of freedom such that P(−t α/2 < T < t α/2) = 1 − α, the confidence intervals on the ratio level k solve:

If a 2 > 0, then the 1 − α confidence interval for the ratio is \( ( - a_{1} \pm \sqrt {a_{1}^{2} - a_{0} a_{2} } )/a_{2} \).Footnote 24 If a 2 < 0 then the confidence interval is unbounded.Footnote 25 In this case, if \( a_{1}^{2} - a_{0} a_{2} < 0 \), then the confidence interval is the entire real line. If a 2 < 0 and \( a_{1}^{2} - a_{0} a_{2} > 0 \), then the confidence interval is the complement of \( ( - a_{1} \pm \sqrt {a_{1}^{2} - a_{0} a_{2} } )/a_{2} \).Footnote 26

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caskey, J.A., Peterson, K. Conservatism measures that control for the effects of economic rents on stock returns. Rev Quant Finan Acc 42, 731–756 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-013-0360-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-013-0360-1