Abstract

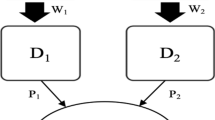

This paper studies the welfare effects of location space constraints when the duopoly sellers are vertically separated. As the downstream firms respond to higher input prices by locating further away from the center of the market, constraining them to locate within the linear city allows the upstream manufacturers better to exploit the downstream industry. This leads to higher final good prices and lower consumer welfare (despite the savings on transportation). This result – which is robust to the inclusion of R&D decisions – is in sharp contrast to the case in which the sellers are vertically integrated. Also different, the incentive to invest in cost-reducing R&D is always insufficient compared with the social optimum. Our results thus suggest the importance of taking into account the vertical market structure in formulating zoning (product standard) and R&D policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Product positioning can be the selection of geographic locations or the choice of product characteristics. In the latter case, constraining the location space could be interpreted as setting a stricter product standard (to conform to consumer preferences).

In addition to mandatory measures, such goals are usually achieved by a combination of economic incentives (e.g., reduced rates of land use) and non-economic incentives (e.g., simplified project approval procedures).

In location-price games with unit consumer demand, total surplus is determined solely by transportation costs, so the comparison is trivial. On the other hand, helping consumers is usually the objective of government policies with respect to firm locations (see, e.g., Matsumura and Matsushima 2012a; Bárcena-Ruiz and Casado-Izaga 2014). In the antitrust literature, consumer welfare is often the focus, instead of total welfare. Besides, sellers of consumer goods may be owned by foreign investors, and their profits are excluded from the regulator’s objective (Cowan 2012).

After all, we often observe shopping centers locating beyond residential areas. For motivating examples on product characteristics being out of the range that consumers most prefer, see for example Tyagi (1999).

For example, mobile food vendors are free to change their locations. In the context of product characteristics, the downstream retailers of a similar product may offer certain add-on services that are differentiated. It is plausible that such services, which are easily varied, are chosen after the input prices are set so that the profitability of the product is fully known.

In Sect. 5, we relax this assumption by allowing firms to invest in cost-reducing R&D.

It is worth noting that the baseline scenario also fits situations in which the input is purchased but from an upstream market that is either perfectly competitive or under price regulation.

This vertical scenario also characterizes situations in which the manufacturers do not sell the products directly to consumers but through their respective retailers. Correspondingly, in the baseline scenario, the manufacturers sell directly to final consumers.

Such an arrangement, which is described as exclusive dealing in the antitrust literature, is a common practice in businesses such as car dealerships, fast food chains, and similar franchise arrangements.

We focus on linear pricing, which is also called a wholesale-price contract in the marketing literature.

These results hold even if \(w_j\ne c\), provided that \(w_j\) is constant.

Since the market is covered, the loss of sales is solely to the other downstream firm.

With location-price competition, a higher cost makes a firm less competitive; and to buffer competition it chooses to locate further away from the center of the market (Tyagi 2001).

If the upstream manufacturers use two-part tariffs in selling the input, the double marginalization problem is eliminated and this result will not be obtained.

According to Porter (1980), low cost and differentiated product are two of the three “generic” competitive strategies of a firm.

Matsumura and Matsushima (2012b) have focused on the comparison of the R&D level only.

The difference in price, as shown in the proof, is equal to the difference in R&D intensities in the two models minus half of t.

The socially optimum R&D level is defined by \(I'(d^{*})=1/2\).

This equilibrium outcome is due to the fact that the market is covered. In the conclusion we briefly discuss what may happen when consumer demand for the final product is elastic.

Flexibility in product positioning or location is even more desired when the downstream firms in the separated structure are local firms but the upstream firms are foreign.

Nonetheless, the magnitude of the price decrease that is due to location flexibility may be changed with elastic consumer demand, and must be weighed against the increase in transportation cost when determining the welfare impact on consumers.

For example, investment in R&D may be targeted to reduce congestion (Matsumura and Matsushima 2007) or transportation cost (von Ungern-Sternberg 1988; Matsumura and Shimizu 2011). In other contexts, there may be spillover effects from R&D (d’Aspremont and Jacquemin 1988), and initial asymmetries between firms can change the R&D results that are obtained under the assumption of symmetric firms (Lahiri and Ono 1999; Kitahara and Matsumura 2006; Ishida et al. 2011).

References

Bárcena-Ruiz, J. C., & Casado-Izaga, F. J. (2014). Zoning under spatial price discrimination. Economic Inquiry, 52(2), 659–665.

Bassi, M., Pagnozzi, M., & Piccolo, S. (2015). Product differentiation by competing vertical hierarchies. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 24(4), 904–933.

Bonanno, G., & Vickers, J. (1988). Vertical separation. Journal of Industrial Economics, 36(3), 257–265.

Brekke, K., & Straume, O. (2004). Bilateral monopolies and location choice. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 34(3), 275–288.

Chen, Y. (2001). On vertical mergers and their competitive effects. RAND Journal of Economics, 32(4), 667–685.

Cowan, S. (2012). Third-degree price discrimination and consumer surplus. Journal of Industrial Economics, 60(2), 333–345.

d’Aspremont, C., Gabszewicz, J. J., & Thisse, J.-F. (1979). On Hotelling’s ‘stability in competition’. Econometrica, 47(5), 1145–1150.

d’Aspremont, C., & Jacquemin, A. (1988). Cooperative and noncooperative R&D in duopoly with spillovers. American Economic Review, 78(5), 1133–1137.

Gu, Y., & Wenzel, T. (2009). A note on the excess entry theorem in spatial models with elastic demand. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27(5), 567–571.

Gupta, S., & Loulou, R. (1998). Process innovation, product differentiation, and channel structure: strategic incentives in a duopoly. Marketing Science, 17(4), 301–316.

Hotelling, H. (1929). Stability in competition. Economic Journal, 39(153), 41–57.

Ishida, J., Matsumura, T., & Matsushima, N. (2011). Market competition, R&D and firm profits in asymmetric oligopoly. Journal Industrial Economics, 59(3), 484–505.

Kitahara, M., & Matsumura, T. (2006). Realized cost-based subsidies for strategic R&D investments with ex ante and ex post asymmetries. Japanese Economic Review, 57(3), 438–448.

Kitahara, M., & Matsumura, T. (2013). Mixed duopoly, product differentiation and competition. Manchester School, 81(5), 730–744.

Lahiri, S., & Ono, Y. (1999). R&D subsidies under asymmetric duopoly: A note. Japanese Economic Review, 50(1), 104–111.

Lambertini, L. (1997). Unicity of the equilibrium in the unconstrained Hotelling model. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 27(6), 785–798.

Matsumura, T., & Matsushima, N. (2007). Congestion-reducing investments and economic welfare in a Hotelling model. Economics Letters, 96(2), 161–167.

Matsumura, T., & Matsushima, N. (2012a). Locating outside a linear city can benefit consumers. Journal of Regional Science, 52(3), 420–432.

Matsumura, T., & Matsushima, N. (2012b). Welfare properties of strategic R&D investments in Hotelling models. Economics Letters, 115(3), 465–468.

Matsumura, T., & Shimizu, D. (2011). Endogenous flexibility in the flexible manufacturing system. Bulletin of Economic Research, 67(1), 1–13.

Matsushima, N. (2004). Technology of upstream firms and equilibrium product differentiation. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 22(8–9), 1091–1114.

Matsushima, N. (2009). Vertical mergers and product differentiation. Journal of Industrial Economics, 57(4), 812–834.

McGuire, T. W., & Staelin, R. (1983). An industry equilibrium analysis of downstream vertical integration. Marketing Science, 2(2), 161–191.

Meza, S., & Tombak, M. (2009). Endogenous location leadership. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27(6), 687–707.

Pagnozzi, M., & Piccolo, S. (2012). Vertical separation with private contracts. Economic Journal, 122(559), 173–207.

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive strategy. New York: The Free Press.

Rey, P., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1995). The role of exclusive territories in producers’ competition. RAND Journal of Economics, 26(3), 431–451.

Tabuchi, T., & Thisse, J.-F. (1995). Asymmetric equilibria in spatial competition. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(2), 213–227.

Tyagi, R. K. (1999). Pricing patterns as outcomes of product positions. Journal of Business, 72(1), 135–157.

Tyagi, R. K. (2000). Sequential product positioning under differential costs. Management Science, 46(7), 928–940.

Tyagi, R. K. (2001). Cost leadership and pricing. Economics Letters, 72(2), 189–193.

von Ungern-Sternberg, T. (1988). Monopolistic competition and general purpose products. Review of Economic Studies, 55(2), 231–246.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the editor, Lawrence J. White, for many valuable comments and suggestions. We also wish to thank two anonymous referees and participants at the Industrial Organization Theory Workshop at Shandong University and the Industrial Organization and International Trade Workshop at Jinan University for helpful comments. Financial support from the National Science Foundation of China (71603083, 71603283) is gratefully acknowledged. The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Lemma 1

We use backward induction to solve this three stage game. Given the costs of the downstream firms (the input prices), the solutions to the pricing and location stages are

The location of the marginal consumer is

In the first stage of input pricing, the first order conditions are

It is easy to verify that the second-order conditions are satisfied.

Solving the two first order conditions, we have

Substituting them back into \(p_a\) and \(p_b\), we have \(p_a=p_b=4t+c\).

The profits that are earned by the downstream firms and the upstream manufacturers are respectively \(\pi _1^{vc}=\pi _1^{vc}=\frac{3t}{2}\) and \(\pi _a^{vc}=\pi _b^{vc}=\frac{t}{2}\), and consumer surplus is

\(\square \)

Proof of Lemma 2

Given the input prices and the locations, the pricing stage is the same as that in the location-constrained model. Solving the first order conditions in the location stage, we have

The location of the marginal consumer is

Moving to the first stage of input-price setting, we have

from which we solve for

The following equilibrium outcomes are then obtained:

\(\square \)

Proof of Result 2

The equilibrium outcomes in the two models can be calculated as follows:

The differences of equilibrium prices, profits, and consumer and social welfare in the two models are

With \(d^{bu}>d^{bc}\) and \(I(d^{bu})>I(d^{bc})\), the signs are all ambiguous. \(\square \)

Proof of Lemma 3

The solutions to the pricing and location stages (and the location of the marginal consumer) are the same as those in Lemma 1. In the input pricing stage, the first-order conditions are

With the second-order conditions being satisfied (\(\frac{\partial ^2 \pi _1}{\partial w_1^2}=\frac{\partial ^2 \pi _2}{\partial w_2^2}=-\frac{1}{3t}.\)), we have

Substituting in the values of p, x and w, we can write manufacturers 1 and 2’s profit as:

The first-order conditions for R&D choices are

The second-order conditions (\(\frac{1}{27t}-I''<0\)) are satisfied when \(I''\) is sufficiently large.

Impose symmetry, and we obtain

\(\square \)

Proof of Lemma 4

The equilibrium prices and locations (and the location of the marginal consumer) given input prices are the same as those in Lemma 2. The first-order conditions in the input-pricing stage are

from which we obtain

Thus manufacturers 1 and 2’s profit could be written as

The first-order conditions in the R&D stage are

The second-order conditions are satisfied when \(I''\) is sufficiently large (\(\frac{4}{81t}-I''<0\)).

At the symmetric equilibrium we have

\(\square \)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Shuai, J. A Welfare Analysis of Location Space Constraints with Vertically Separated Sellers. Rev Ind Organ 52, 161–177 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-017-9568-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-017-9568-x