Abstract

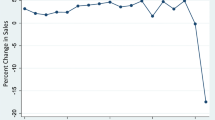

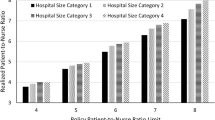

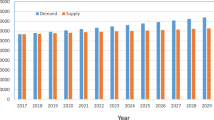

The regulation of nursing homes in the U.S. often includes mandates that require a minimum nurse staffing level. In this paper, we exploit new minimum nurse staffing regulations by the states of New Mexico and Vermont that were implemented in the early 2000s to determine how nursing homes responded in terms of staffing, quality, and the decision to exit the market. Our identification strategy exploits the fact that some nursing homes had pre-regulatory staffing levels near the new requirement and did not need to change staffing levels. We compare these nursing homes to a group that faced binding constraints (low-staffed) and those that were significantly over the constraint (high-staffed). Low-staffed nursing homes increase staffing levels but also use less expensive nurse types to satisfy the new standard. High-staffed nursing homes decrease staffing and use fewer contracted staff. Overall, dispersion in staffing is reduced, but we find little effect by pre-regulatory staffing level on non-staffing measures of quality and the decision to exit the market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Nursing homes are allowed to apply for waivers from the RN staffing requirement. A nursing home must show hardship in order to be granted a waiver; and, therefore, waivers only tend to be granted to small nursing homes.

While OBRA did not specifically define “sufficient” staffing, there are at least three mechanisms that potentially deter nursing homes from understaffing their facilities: First, states may implement minimum staffing regulations which include a specific minimum nurse-to-resident ratio. These regulations are the focus of this paper. Second, states are required to inspect each nursing home on an annual basis. If state regulations determine that the nursing home does not employ “sufficient” staff, the regulators may issue a regulatory deficiency citation, fine, and/or closure of the facility. Third, understaffing a facility may lead to a greater number of accidents, and litigation risk may act as a deterrent to understaffing.

New Mexico required that a licensed nurse be on duty at all times and there must be a full-time director of nursing (NMAC 7.9.2.51). According to Section 7.13 of Vermont’s Licensing and Operating Rules for Nursing Homes, nursing homes are required to have a licensed nurse on duty at all times, at least eight hours a day must be from staffed by an RN, and included in those RN hours is a RN director of nursing.

Senate Bill 194 was vetoed in April of 1997. Governor Gary Johnson held office from 1995 and 2003. Source: “Governor Vetoes Nursing Home Bill.” April 11, 1997. Albuquerque Journal.

Source: “Vermont Weighs Nursing Home Rules.” July 30, 2001. The Burlington Free Press.

Occasionally, OSCAR reports staffing levels that are unreliable. These observations are not utilized in this analysis. Unreliable observations for total staffing levels are identified as those with more than twenty-four hours of staffing, zero staffing, and (among those surveys that do not fall within the first two criteria) nursing homes that have staffing levels that are three standard deviations outside the mean.

While nursing homes are required to be surveyed every 12 months, longer intervals do occur causing there to be fewer observations for the 104 nursing homes than expected.

Hausman tests found that all models should include fixed effects and not random effects.

For example, it is expected that nursing homes will hire cheaper CNAs if they need to increase staffing or fire more expensive RNs if they need to reduce staffing. Composition may change without changes in staffing levels of certain nurses.

Pressure ulcers, contractures, and physical restraints are calculated as the percentage of residents that acquired the condition at the facility. The number of facility-acquired conditions is defined as the number of residents currently with the condition minus the number of residents that had the condition prior to admission. If a nursing home is able to restore functioning, it is possible for these measures to have negative values.

Summary statistics are reported for all 582 observations. For licensed staffing regressions, the minimum licensed staff reported is zero. Since this is not allowed by law, these observations are excluded from regressions that use RN or licensed staff levels/composition as a dependent variable.

We also estimates the models using linear probability models, logit and probit, but many of the control variables perfectly predicted the outcome. This made the models unstable and highly dependent on the controls that are included in the model.

In the case of the three facility-acquired quality measures, negative values may arise if the nursing home is able to improve the health of a resident. Therefore, in these models we restrict the sample to observations with non-negative quality.

Since negative values may arise for facility-acquired quality measures, we also estimate Tobit models on the assumption that all quality measures are truncated at zero. The results are not sensitive to truncation.

Furthermore, we estimate separate models for low, control, and high-staffed nursing homes and compare the effects of all control variables across all three types. The effect of all of the control variables are found to be statistically similar.

While we find two statistically significant effects for high-staffed nursing homes, these findings contradict expectations as these facilities reduced staffing but saw improvements in quality.

References

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust difference-in-differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275.

Bowblis, J. R. (2011a). Ownership conversion and closure in the nursing home industry. Health Economics, 20(6), 631–644.

Bowblis, J. R. (2011b). Staffing ratios and quality: An analysis of minimum direct care staffing requirements in nursing homes. Health Services Research, 46(5), 1495–1516.

Bowblis, J. R. (2015). The cost of regulation: More stringent staff regulations and nursing home financial performance. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 47(3), 325–338.

Bowblis, J. R., & Hyer, K. (2013). Nursing home staffing requirements and input substitution: Effects on housekeeping, food service and activities staff. Health Services Research, 48(4), 1539–1550.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS]. (2015). Interpretive guidelines for long-term facilities, appendix PP-guidance to surveyors for long-term care facilities. State Operations Manual. Baltimore, MD: CMS.

Chen, M., & Grabowski, D. C. (2015). Intended and unintended consequence of minimum staffing standards for nursing homes. Health Economics, 24(7), 822–839.

Chen, M., & Serfes, K. (2012). Minimum quality standard regulation under imperfect quality observability. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 41(2), 269–291.

Chou, S.-Y. (2002). Asymmetric information, ownership and quality of care: An empirical analysis of nursing homes. Journal of Health Economics, 21(2), 293–311.

Cohen, J. W., & Spector, W. D. (1996). The effect of Medicaid reimbursement on quality of care in nursing homes. Journal of Health Economics, 15(1), 23–48.

Cook, A., Gaynor, M., Stephens, M., & Taylor, M. (2012). The effect of a hospital nurse staffing mandate on patient health outcomes: Evidence from California’s minimum staffing regulation. Journal of Health Economics, 31(2), 340–348.

Crampes, C., & Hollander, A. (1995). Duopoly and quality standards. European Economic Review, 39(1), 71–82.

Hotz, V. J., & Xiao, M. (2011). The impact of regulations on the supply and quality of care in child care markets. American Economic Review, 101(5), 1775–1805.

Leland, H. E. (1979). Quacks, lemons, and licensing: A theory of minimum quality standards. Journal of Political Economy, 87(6), 1328–1346.

Lin, H. (2014). Revisiting the relationship between nurse staffing and quality of care in nursing homes: An instrumental variables approach. Journal of Health Economics, 37(1), 13–24.

Matsudaira, J. D. (2014a). Government regulation and the quality of healthcare: Evidence from minimum staffing legislation for nursing homes. Journal of Human Resources, 49(1), 32–72.

Matsudaira, J. D. (2014b). Monopsony in the low-wage labor market? Evidence from minimum nurse staffing regulations. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 96(1), 92–102.

Mueller, C., Arling, G., Kane, R., Bershadsky, J., Holland, D., & Joy, A. (2006). Nursing home staffing standards: their relationship to nurse staffing levels. Gerontologist, 46(1), 74–80.

Omnibus Reconciliation Act, PL No. 100-203. (1987).

Park, J., & Stearns, S. C. (2009). Effects of state minimum staffing standards on nursing home staffing and quality of care. Health Services Research, 44(1), 56–78.

Ronnen, U. (1991). Minimum quality standards, fixed costs, and competition. The Rand Journal of Economics, 22(4), 490–504.

Scarpa, C. (1998). Minimum quality standards with more than two firms. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 16(5), 665–676.

Shapiro, C. (1983). Premiums for high quality products as returns to reputations. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(4), 659–680.

Valletti, T. M. (2000). Minimum quality standards under Cournot competition. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 18(3), 235–245.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge seminar participants at IUPUI, Yaa Akosa Antwi, John Bailer, Christopher Brunt, Michael Curme, Chuck Moul, and the editor Lawrence White for helpful comments. Andrew Ghattas would also like to acknowledge financial support from Miami University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bowblis, J.R., Ghattas, A. The Impact of Minimum Quality Standard Regulations on Nursing Home Staffing, Quality, and Exit Decisions. Rev Ind Organ 50, 43–68 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-016-9528-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-016-9528-x