Abstract

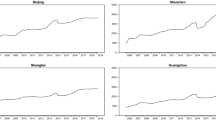

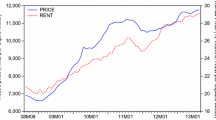

This study applies the dynamic Gordon growth model which is in the circumstance of rational bubbles to decompose log price-rent ratio into three parts, i.e., rational bubbles, discounted expected future rent growth rates and discounted expected future returns. The latter two terms represent housing fundamentals. The magnitudes of the components of price-rent ratio’s variance are estimated to distinguish the relative impact of the three parts on housing prices. Using time series data from the housing markets in the four largest cities in China (1991:Q1–2011:Q1 for Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen; 1993:Q2–2011:Q1 for Beijing), this paper presents a number of empirical findings: (a) the variance of rational bubbles is much larger than the variance of price-rent ratio, and rational bubbles contribute more fluctuations directly to price-rent ratio than the expected returns or the expected rent growth rates do; (b) the covariance between rational bubbles and expected returns or expected rent growth rates is also large; (c) the positive covariance of rational bubbles and expected returns implies that high expected returns coexist with bubbles, which differs from previous findings that lower expected returns drive asset prices; (d) the negative covariance of rational bubbles and expected rent growth rates indicates that the larger the bubbles are, the lower the expected rent growth rates are; (e) the positive covariance of expected returns and expected rent growth rates reveals under-reaction of the housing markets to rents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Brunnermeier and Julliard (2008) suggest that the mispricing provided by the dynamic Gordon growth model captures bubbles.

These studies include the overall bond markets (Campbell and Ammer 1993), the interaction between global stock (Ammer and Mei 1996), the influence of monetary policy on stock returns (Patelis 1997), the individual stocks (Vuolteenaho 2002), intertemporal CAPM model (Campbell and Vuolteenaho 2004a), inflation’s impact on the stock markets (Bekaert and Engstrom 2010), and so on.

DTZ, a UGL company and one of the five famous international real estate consultants, has 26,000 permanent employees and 47,000 personnel including contractors, operating across 208 offices in 52 countries throughout Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia and the Pacific and the Americas. See the company’s web site http://www.dtz-ugl.com/content/corporate-Information.

This data is up to 2011 because of the discontinuity of DTZ index data. The study of China’s housing markets, and even the world housing markets is restricted to the time span of the data. The studies of China’s housing markets often use the data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China. This data series started from 1998 (“Dreger and Zhang 2011” is cited in text but not given in the reference list. Please provide details in the list or delete the citation from the text. Dreger and Zhang 2011; Wu, et al. 2012) while Chinese housing markets prices increased sharply at that time. However, the data series do not go through an overall cycle. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether there is a bubble in the markets (Wu, et al. 2012). Fortunately, from Fig. 1 in this paper, we can see intuitively that our data series has experienced both the increase and the decrease, and go through an overall cycle.

Campbell et al. (2009) find that the average rental yield (i.e., the house rent-price ratio) in a dozen of U.S. cities from 1975 to 2007 is 6.03 %, that is to say, the price-to-rent ratio is 16.58.

We construct the benchmark model of VAR system which contains three state variables, the same as Brunnermeier and Julliard (2008) and Hayunga and Lung (2011). What’s more, their structural VAR system variables contained inflation, because they need to test the inflation illusion assumption in the housing markets.

Hiebert and Sydow (2011) set up a VAR system which contains the growth rate of per capita disposable income as the macroeconomic state variable. Campbell et al. (2009) set up VAR system which contains growth rate of per capita disposable income, employment growth rate and population growth rate as the macroeconomic state variables. Engsted and Pedersen (2014) set up a VAR system which contains GDP growth, unemployment, and the spread between short-term and long-term interest rate as the macroeconomic state variables. In this paper, three macroeconomic variables data in the four cities are taken from the bureau of statistics web site in each city, but most of them are the annual data. In order to unify analysis, this paper refers to Campbell et al. (2009), assuming that the annual growth rate of per capita disposable income, the annual growth rate of employed population and the annual growth rate of population in the four quarters of the year is fixed.

References

Ammer, J., & Mei, J. (1996). Measuring international economic linkages with stock market data. Journal of Finance, 51(5), 1743–1763.

Balke, N. S., & Wohar, M. E. (2009). Market fundamentals versus rational bubbles in stock prices: a bayesian perspective. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 24, 35–75.

Bekaert, G., & Engstrom, E. (2010). Inflation and the stock market: understanding the ‘Fed Model’. Journal of Monetary Economics, 57(3), 278–294.

Blanchard, O., & Watson, M. (1982). Bubbles, rational expectations, and financial markets. In P. Wachter (Ed.), Crises in the economic and financial structure (pp. 295–316). Lexington: Lexington Books.

Brooks, C., & Katsaris, A. (2005). A three-regime model of speculative behaviour: modeling the evolution of the S&P 500 composite index. Economic Journal, 115, 767–797.

Brunnermeier, M. K. (2008). Bubbles. In S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (Eds.), New Palgrave dictionary of economics. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brunnermeier, M. K., & Julliard, C. (2008). Money illusion and housing frenzies. Review of Financial Studies, 21(1), 135–180.

Brunnermeier, M. K., & Oehmke, M.(2013). Bubbles, financial crises and systemic risk. In George M. Constantinides, Rene Stulz and Milton Harris (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of finance. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Campbell, J. Y. (1991). A variance decomposition for stock returns. Economic Journal, 101, 157–179.

Campbell, J. Y., & Ammer, J. (1993). What moves the stock and bond markets? A variance decomposition for long-term asset returns. Journal of Finance, 1, 3–37.

Campbell, J. Y., & Shiller, R. J. (1988). The dividend-price ratio and expectations of future dividends and discount factors. Review of Financial Studies, 1, 195–228.

Campbell, J. Y., & Vuolteenaho, T. (2004a). Bad beta, good beta. American Economic Review, 94(5), 1249–1275.

Campbell, J. Y., & Vuolteenaho, T. (2004b). Inflation illusion and stock prices. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 94(2), 19–23.

Campbell, S. D., Davis, M. A., Gallin, J., & Martin, R. F. (2009). What moves housing markets: a variance decomposition of the rent–price ratio. Journal of Urban Economics, 66, 90–102.

Campbell, J. Y., Polk, C., & Vuolteenaho, T. (2010). Growth or glamour? Fundamentals and systematic risk in stock returns. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 305–344.

Case, K. E., & Shiller, R. J. (2003). Is there a bubble in the housing market? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 299–362.

Chen, X., & Funke, M. (2013). Real-time warning signs of emerging and collapsing Chinese house price bubbles. National Institute Economic Review, 223, 39–48.

Chen, Y., Chen, J., & Liu, R. (2009). Cost of ownership, investors’ expectations, and housing price fluctuations: research about the experience of housing market in four major domestic cities. The Journal of World Economy, 10, 14–24.

Cochrane, J. H. (2011a). Discount rates (Presidential address). Journal of Finance, 66, 1047–1108.

Cochrane, J. H. (2011b). How did Paul Krugman get it so wrong? Economic Affairs, 31, 36–40.

Dreger, C., & Zhang, Y. (2011). Is there a bubble in the Chinese housing market? Working Paper, European Regional Science Association.

DTZ Research (2011). DTZ index-Chinese Mainland. Hong Kong: DTZ.

Engsted, T., & Pedersen, T. Q. (2014). Housing market volatility in the OECD area: evidence from VAR based return decompositions. Journal of Macroeconomics, 42, 91–103.

Engsted, T., Hviid, S. J., & Pedersen, T. Q. (2016). Explosive bubbles in house prices: evidence from the OECD countries. Journal of International Financial markets, Institutions & Money, 40, 14–25.

Favilukis, J., Ludvigson, S., & Van Niewerburgh, S. (2013). The macroeconomic effects of housing wealth, housing finance, and limited risk-sharing in general equilibrium. Working Paper,New York University.

Flood, R. P., & Hodrick, R. J. (1990). On testing for speculative bubbles. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(2), 85–101.

Gallin, J. (2008). The long-run relationship between house prices and rents. Real Estate Economics, 36, 635–658.

Gelain, P., & Lansing, K. L. (2014). House prices, expectations, and time-varying fundamentals. Journal of Empirical Finance, 29, 3–25.

Ghysels, E., Plazzi, A., Torous, W., & Valkanov, R. (2012). Forecasting real estate prices. In Elliott, G. and A. Timmermann (Eds.), Handbook of economic forecasting. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Girouard, N., Kennedy, M., van den Noord, P., & André, C. (2006). Recent house price developments: the role of fundamentals. OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 475.

Hamilton, B. W., & Schwab, R. M. (1985). Expected appreciation in urban housing markets. Journal of Urban Economics, 18, 103–118.

Hayunga, D. K., & Lung, P. P. (2011). Explaining asset mispricing using the resale option and inflation illusion. Real Estate Economics, 39(2), 313–344.

Hiebert, P., & Sydow, M. (2011). What drives returns to euro area housing? Evidence from a dynamic dividend-discount model. Journal of Urban Economics, 70, 88–98.

Himmelberg, C., Mayer, C., & Sinai, T. (2005). Assessing high house prices: bubbles, fundamentals and misperceptions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 67–92.

Hou, Y. (2010). Housing price bubbles in Beijing and Shanghai? A multi-indicator analysis. International Journal of Housing markets and Analysis, 3(1), 17–37.

Hui, E. C. M., & Wang, Z. (2014). Market sentiment in private housing market. Habitat International, 44, 375–385.

Hui, E. C. M., & Wang, G. (2015). A new optimal portfolio selection model with owner-occupied housing. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computation, 270, 714–723.

Hui, E. C. M., & Yue, S. (2006). Housing price bubbles in Hong Kong, Beijing and Shanghai: a comparative study. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 33(4), 299–327.

Kim, J. Y. (1994). Bayesian asymptotic theory in a times series model with a possible nonstationary process. Econometric Theory, 10(3), 764–773.

Kim, K., & Suh, S. H. (1993). Speculation and price bubbles in the Korean and Japanese real estate markets. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 6(1), 73–87.

Krainer, J., & Wei, C. (2004). House prices and fundamental value. FRBSF Economic Letter, November-October, 1–3.

Lv. (2010). The measurement of bubbles level of urban housing market in China. Economic Research Journal, (6), 28–41.

Meese, R., & Wallace, N. (1994). Testing the present value relation for housing prices: should I leave my house in San Francisco? Journal of Urban Economics, 35, 245–266.

Patelis, A. D. (1997). Stock return predictability, & the role of monetary policy. Journal of Finance, 52(5), 1951–1972.

Plazzi, A., Torous, W., & Valkanov, R. (2010). Expected returns and expected growth in rents of commercial real estate. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 3469–3519.

Ren, Y., Xiong, C., & Yuan, Y. (2012). House price bubbles in China. China Economic Review, 23(4), 786–800.

Shen, Y., & Liu, H. Y. (2004). Residential property prices and economic fundamentals: an empirical study of 14 cities in China during 1995–2002. Economic Research Journal, 6, 78–76.

Tirole, J. (1982). On the possibility of speculation under rational expectations. Econometrica, 50, 1163–1181.

Van Norden, S. (1996). Regime switching as a test for exchange rate bubbles. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11, 219–251.

Vuolteenaho, T. (2002). What drives firm level stock returns. Journal of Finance, 57, 23–64.

Weeken, O. (2004). Asset pricing and the housing market. In: Bank of England quarterly bulletin. Spring.

Wu, J., Gyourko, J., & Deng, Y. (2012). Evaluating conditions in major Chinese housing markets. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 42, 531–543.

Acknowledgments

We thank Meijie Zhu, Mengsi Luo and two anonymous referees for very helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Renhe Liu acknowledges the financial support of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 14BJY186) and the Philosophy and Science Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (No. GD12CYJ07).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R., Hui, E.Cm., Lv, J. et al. What Drives Housing Markets: Fundamentals or Bubbles?. J Real Estate Finan Econ 55, 395–415 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9565-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-016-9565-0