Abstract

Using adverse-selection cost as a proxy for information asymmetry, we find evidence that non-GAAP earnings numbers issued by management (pro forma earnings) and analysts (street earnings) improve price discovery. First, information asymmetry before an earnings announcement is positively associated with the probability of a non-GAAP earnings number at the forthcoming earnings announcement. Second, the post-announcement reduction in information asymmetry is greater when managers or analysts issue non-GAAP earnings at the earnings announcement and when the magnitude of the non-GAAP earnings adjustment is larger. Our results suggest that earnings adjustments by analysts and managers increase the amount and precision of earnings information and help to narrow information asymmetry between informed and uninformed traders following earnings announcements. Alternatively, the findings may be attributable to characteristics of non-GAAP firms and overall better reporting quality for those firms rather than non-GAAP earnings disclosure per se.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I/B/E/S (2001, p. 7) states: “There is no ‘right’ answer as to when a non-extraordinary charge is nonrecurring or non-operating and deserves to be excluded from the earnings basis used to value the company’s stock. We believe the ‘best’ answer is what the majority wants to use, in that the majority basis is likely what is reflected in the stock price.” Lambert (2004), however, points out the difficulty surrounding the classification of an item as “nonrecurring.”

The NASDAQ saw dramatic changes in the early 2000s because of the growth of electronic communication networks, which enable investors to submit anonymous limit orders and trade directly with each other (Barclay et al. 2003).

In robustness checks using a street selection model excluding five variables related solely to earnings informativeness and missed earnings targets (i.e., INTANGIBLES, MTB, LEVERAGE, negOPFE, and OPLOSS), we find results for analysts (untabulated) very nearly identical to our reported findings.

In robustness tests, we also included an indicator variable for Regulation G in the selection model. That variable is not significant in any case.

Equation (3) does not include changes in lnMV, ANALYSTS, and BTM because size, number of analysts, and book-to-market for any firm-quarter are essentially fixed. Additionally, ASCpre in Eq. (3) already reflects size, number of analysts, and book to market. Omitting size, however, may be a special concern because small firms typically have more informative earnings announcements than large firms. We reran the model including size (lnMV). Size is not significant, and its inclusion does not affect any inferences.

We choose NASTRAQ intra-day data over TAQ data for three reasons. First, NASTRAQ permits accurate matching of trade and quote data because actual trade execution times are known; TAQ stamps a trade based on when it is reported rather than when it is executed. Second, unlike TAQ, NASTRAQ does not round transaction sizes and prices.

When we drop firm size (lnMV) from the regression model, we find a negative coefficient on ANALYSTS (p ≤ 0.001) in all regressions (not tabulated), consistent with lower adverse-selection cost as analyst coverage increases.

The negative coefficient on IMR indicates that the error terms in the selection (e) and outcome (u) equations are negatively correlated (σ e,u < 0), suggesting that common unobservable factors that are positively associated with the likelihood of non-GAAP earnings are also negatively associated with the pre-announcement adverse-selection cost. Because adverse selection is negatively associated with IMR and positively associated with the selection of non-GAAP earnings, the coefficient on the treatment variable (NonGAAP) would be biased toward zero if IMR were omitted from the outcome equation. In other words, the incremental adverse-selection cost associated with non-GAAP earnings (treatment effect) would be understated without an adjustment for self-selection.

The positive coefficient on IMR indicates that error terms in the selection (e) and outcome (u) equations are positively correlated (σ e,u > 0), suggesting that common unobservable factors that are positively associated with the selection of non-GAAP earnings are also positively associated with the post-announcement change in adverse selection cost. Because the change in adverse selection is positively associated with IMR and negatively associated with the selection of non-GAAP earnings, the coefficient on the treatment variable (Non-GAAP) would be biased toward zero if the inverse Mills ratio were omitted from the outcome equation. In other words, our estimates of the magnitude of the reduction in adverse-selection cost due to non-GAAP earnings would be understated without an adjustment for self-selection bias.

The coefficients reported in Table 6 for any variable with RANKabsEXs are the actual coefficients multiplied by 100. The actual coefficients for RANKabsEXs for columns (a) and (b) are 0.000,992 and 0.000871, respectively. For street quarters, an increase in absolute exclusion from the 25th to the 75th percentile would decrease adverse-selection cost by 0.0496 cents per share (=50 × −0.000992), or 3.4 % of the mean level ASC per share (−0.0496/1.459 = −0.03399). For pro forma quarters, an increase in the absolute exclusion from the 25th to the 75th percentile would decrease adverse-selection cost by 0.04355 cents per share (=50 × −0.000871), or 3.2 % of the mean level ASC per share (−0.04355/1.382 = −0.03151).

We reran Model 1 for street earnings restricted to cases where managers did not report pro forma earnings (n = 6903); the coefficient on RankEX is negative (−0.1008) and significant (p ≤ 0.001). Thus results for the restricted sample are nearly identical to the full sample results. We also reran Model 1 for pro forma earnings restricted to cases where I/B/E/S did not report street earnings (n = 348); the coefficient on RankEX is negative (−0.3360) and significant (p = 0.046).

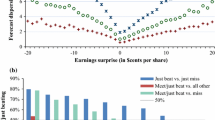

Formally, let FE (forecast error) = non-GAAP EPS − I/B/E/S median forecast EPS, and let EX (total exclusion) = non-GAAP EPS − GAAP EPS before extraordinary items. We select all cases with EX > 0 and then form an indicator variable, FE_FLIPS, where FE_FLIPS equals 1 if FE – EX < 0 and FE ≥ 0 and 0 otherwise.

The Lin et al. (1995) model is used widely in market microstructure studies to measure the adverse-selection component of the bid-ask spread. Prior studies that use this model include Chung et al. (2006), Barclay and Hendershott (2004), Van Ness et al. (2005), and Chung and Li (2003). Barclay and Hendershott (2004) suggest that the model does not rely on inventory-induced trade reversals and also does not require a constant effective spread. The model follows Huang and Stoll (1994) and permits a separate estimate of fixed and dealer profit components. We thank David Dubofsky for bringing many of these points to our attention.

The use of the effective spread in the Lin et al. (1995) model allows for trades that are executed inside or outside the quoted spread. The Masson (1993) model uses only those trades at bid quote or ask quote. Using a sample of 313 stocks traded on NASDAQ between September 27, 1996, and September 29, 1997, Ellis et al. (2000) find that 20.4 and 4.93 % of the trades in their sample occur inside and outside the quoted spread, respectively. For an inside (outside) trade, the effective spread is smaller (larger) than the quoted spread.

References

Abarbanell, J., & Lehavy, R. (2007). Letting the “tail wag the dog”: The debate over GAAP versus street earnings revisited. Contemporary Accounting Research, 24(3), 675–723.

Allee, K. D., Bhattacharya, N., Black, E. L., & Christensen, T. E. (2007). Pro forma disclosure and investor sophistication: External validation of experimental evidence using archival data. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32, 201–222.

Bacidore, J. (1997). The impact of decimalization on market quality: An empirical investigation of the Toronto Stock Exchange. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 6, 91–120.

Bacidore, J. (2001). Decimalization, adverse selection, and the market rents. Journal of Banking & Finance, 25, 829–855.

Baik, B., Farber, D., & Petroni, K. (2009). Analysts’ incentives and street earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 47, 45–69.

Barclay, M., & Hendershott, T. (2004). Liquidity externalities and adverse selection: Evidence from trading after hours. Journal of Finance, 59, 681–710.

Barclay, M., Hendershott, T., & McCormick, D. (2003). Competition among trading venues: Information and trading on electronic communications networks. Journal of Finance, 58, 2637–2665.

Barron, O. E., Byard, D., & Kim, O. (2002). Changes in analysts’ information around earnings announcements. The Accounting Review, 77(4), 821–846.

Barron, O. E., Kim, O., Lim, S. C., & Stevens, D. E. (1998). Using analysts’ forecasts to measure properties of analysts’ information environment. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 421–433.

Barth, M., Beaver, W., & Landsman, W. (1998). Relative valuation roles of equity book value and net income as a function of financial health. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25, 1–34.

Barth, M., Gow, I. D., & Taylor, D. J. (2012). Why do pro forma and street earnings not reflect changes in GAAP? Evidence from SFAS 123R. Review of Accounting Studies, 17, 526–562.

Bessembinder, H. (1997). Endogenous changes in the minimum tick: An analysis of Nasdaq securities trading near ten dollars. Working paper, Arizona State University.

Bhattacharya, N., Black, E. L., Christensen, T. E., & Larson, C. R. (2003). Assessing the relative informativeness and permanence of pro forma earnings and GAAP operating earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 36, 285–319.

Bhattacharya, N., Black, E. L., Christensen, T. E., & Mergenthaler, R. D. (2004). Empirical evidence on recent trends in pro forma reporting. Accounting Horizons, 18, 27–43.

Bhattacharya, N., Black, E. L., Christensen, T. E., & Mergenthaler, R. D. (2007). Who trades on pro forma earnings information? The Accounting Review, 82, 581–619.

Bhattacharya, N., Desai, H., & Venkataraman, K. (2012). Does earnings quality affect information asymmetry? Evidence from trading costs. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(2), 482–516.

Black, D. E., Black, E. L., Christensen, T. E., & Heninger, W. G. (2012). Has the regulation of pro forma reporting in the U.S. changed investors’ perceptions of pro forma earnings disclosure? Journal of Business, Finance, & Accounting, 39, 876–904.

Black, D. E., & Christensen, T. E. (2009). US managers’ use of ‘pro forma’ adjustments to meet strategic earnings targets. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 36, 297–326.

Botosan, C., Plumlee, M., & Xie, Y. (2004). The role of information precision in determining the cost of equity capital. Review of Accounting Studies, 9, 233–259.

Bowen, R. M., Davis, A. K., & Matsumoto, D. A. (2005). Emphasis on pro forma versus GAAP earnings in quarterly press releases: Determinants, SEC intervention, and market reaction. The Accounting Review, 80, 1011–1038.

Bradshaw, M. T., & Sloan, R. G. (2002). GAAP versus the street: An empirical assessment of two alternative definitions of earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 41–66.

Brooks, R. M. (1994). Bid-ask spread components around anticipated announcements. The Journal of Financial Research, 3, 375–386.

Brown, N. C., Christensen, T. E., & Elliott, W. B. (2012a). The timing of quarterly “pro forma” earnings announcements. Journal of Business, Finance & Accounting, 39, 315–359.

Brown, N. C., Christensen, T. E., Elliott, W. B., & Mergenthaler, R. D. (2012b). Investor sentiment and pro forma earnings disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 50, 1–40.

Brown, S., Hillegeist, S., & Lo, K. (2009). The effect of earnings surprises on information asymmetry. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 47, 208–225.

Brown, L. D., & Sivakumar, K. (2003). Comparing the value relevance of two operating income measures. Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 561–572.

Chen, C. Y. (2010). Do analysts and investors fully understand the persistence of the items excluded from Street earnings? Review of Accounting Studies, 15, 32–69.

Christensen, T., Drake, M. S., & Thornock, J. R. (2014). Optimistic reporting and pessimistic investing: Do pro forma earnings disclosures attract short sellers? Contemporary Accounting Research, 31, 67–102.

Chung, K. H., Chuwonganant, C., & McCormick, D. T. (2006). Order preferencing, adverse selection costs, and the probability of information-based trading. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 27, 343–364.

Chung, K. H., & Li, M. (2003). Adverse-selection costs and the probability of information-based trading. The Financial Review, 38, 257–272.

Cready, W., Kumas, A., & Subasi, M. (2014). Are trade size-based inferences about traders reliable? Evidence from institutional earnings-related trading. Journal of Accounting Research, 32, 877–909.

Demestz, H. (1968). The cost of transacting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87, 33–53.

Diamond, D. W. (1985). Optimal release of information by firms. The Journal of Finance, 40, 1071–1094.

Diamond, D. W., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1991). Disclosure, liquidity and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance, 46, 1325–1359.

Doyle, J., Lundholm, R., & Soliman, M. (2003). The predictive value of expenses excluded from pro forma earnings. Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 145–174.

Eleswarapu, V. R., Thompson, R., & Venkataraman, K. (2004). The impact of Regulation Fair Disclosure: Trading costs and information asymmetry. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 39(2), 209–225.

Elliott, W. B. (2006). Are investors influenced by pro forma emphasis and reconciliations in earnings announcements? The Accounting Review, 81, 113–133.

Ellis, K., Michaely, R., & O’Hara, M. (2000). The accuracy of trade classification rules: Evidence from NASDAQ. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 35, 529–552.

Entwistle, G. M., Feltham, G. D., & Mbagwu, C. (2006). Financial reporting regulation and the reporting of pro forma earnings. Accounting Horizons, 20, 39–55.

Frankel, R., & McVay, S. (2011). Non-GAAP earnings and board independence. Review of Accounting Studies, 16, 719–744.

Frederickson, J. R., & Miller, J. S. (2004). The effects of pro forma earnings disclosures on analysts’ and nonprofessional investors’ equity valuation judgments. The Accounting Review, 79, 667–686.

Glushkov, D., & Robinson D. (2006). A note on IBES unadjusted data, WRDS Documentation on IBES. http://wrds.wharton.upenn.edu/ds/ibes/lib/IBES_Unadjusted_Data.pdf.

Graham, J. R., Harvey, C. R., & Rajgopal, S. (2005). The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40, 3–73.

Gu, Z., & Chen, T. (2004). Analysts’ treatment of nonrecurring items in street earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 38, 129–170.

Healy, P. M., & Palepu, K. G. (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital market: a review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31, 405–440.

Heflin, F., & Hsu, C. (2008). The impact of SEC’s regulation of non-GAAP disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 46, 349–365.

Huang, R., & Stoll, H. (1994). Market microstructure and stock return predictions. The Review of Financial Studies, 7, 179–213.

Huang, R., & Stoll, H. (1996). Dealer versus auction markets: A paired comparison of execution costs on NASDAQ and the NYSE. Journal of Financial Economics, 41, 313–357.

I/B/E/S. (2001). Monthly Comments (February): Francis, J., Q. Chen, D. R. Philbrick, and H.W. Richard. 2004. Security Analyst Independence. CFA Research Foundation Publications: 1–107.

Johnson, W. B., & Schwartz, W. C. (2005). Are investors misled by “pro forma” earnings? Contemporary Accounting Research, 22, 915–963.

Kim, O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1991). Market reaction to anticipated announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 30, 273–309.

Kim, O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1994). Market liquidity and volume around earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 17, 41–67.

Kim, O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1997). Pre-announcement and event-period private information. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24, 395–419.

Kolev, K., Marquardt, C. A., & McVay, S. E. (2008). SEC scrutiny and the evolution of non-GAAP reporting. The Accounting Review, 83, 157–184.

Krinsky, I., & Lee, J. (1996). Earnings announcements and the components of the bid-ask spread. The Journal of Finance, 51, 1523–1535.

Lambert, R. A. (2004). Discussion of analysts’ treatment of non-recurring items in street earnings and loss function assumptions in rational expectations tests on financial analysts’ earnings forecasts. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 38, 205–222.

Landsman, W., Miller, B., & Yeh, S. (2007). Implication of components of income excluded from pro forma earnings for future profitability and equity valuation. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 34, 650–675.

Lee, C. M. C., Mucklow, B., & Ready, M. J. (1993). Spreads, depths, and the impact of earnings information: An intraday analysis. The Review of Financial Studies, 6, 345–374.

Lev, B. (1988). Toward a theory of equitable and efficient accounting policy. The Accounting Review, 63, 1–21.

Li, K., & Prabhala, N. (2007). Self-selection models in corporate finance. In B. Espen Eckbo (Ed.), Handbook of corporate finance: Empirical corporate finance (Vol. 1, pp. 37–86). New York: North Holland.

Lin, J., Sanger, G. C., & Booth, G. G. (1995). Trade size and components of the bid-ask spreads. The Review of Financial Studies, 8, 1153–1183.

Lougee, B. A., & Marquardt, C. A. (2004). Earnings informativeness and strategic disclosure: An empirical examination of “pro forma” earnings. The Accounting Review, 79, 769–795.

Marques, A. (2006). SEC interventions and the frequency and usefulness of non-GAAP financial measures. Review of Accounting Studies, 11, 549–574.

Masson, J. (1993). Estimating the components of the bid-ask spread. Working paper. University of Ottawa.

Mayhew, S. (2002). Competition, market structure, and bid-ask spread in stock option markets. The Journal of Finance, LVII, 931–958.

McNichols, M., & Trueman, B. (1994). Public disclosure, private information collection, and short-term trading. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 17, 69–94.

Ng, J., Verrecchia, R., & Weber, J. (2009). Firm performance measures and adverse selection. Working paper. Sloan School of Management at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and The Wharton School at University of Pennsylvania.

Payne, J., & Thomas, W. (2003). The implications of using stock-split adjusted I/B/E/S data in empirical research. The Accounting Review, 78, 1049–1067.

Petersen, M. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 435–480.

Philbrick, D. R., & Ricks, W. E. (1991). Using Value Line and IBES analyst forecasts in accounting research. Journal of Accounting Research, 29, 397–417.

Sadka, R., & Scherbina, A. (2007). Analyst disagreement, mispricing, and liquidity. The Journal of Finance, 62(5), 2367–2403.

Schrand, C. M., & Walther, B. (2000). Strategic benchmarks in earnings announcements: The selective disclosure of prior-period earnings components. The Accounting Review, 75, 151–176.

Stoll, H. R. (1978). The supply of dealer services in securities markets. Journal of Finance, 33, 1133–1151.

Tinic, S. (1972). The economics of liquidity service. Quarterly Journal Economics, 86, 79–93.

Van Ness, B. F., Van Ness, R. A., & Warr, R. (2001). How well do adverse selection components measure adverse selection? Financial Management, 30, 77–98.

Van Ness, B. F., Van Ness, R. A., & Warr, R. (2005). The impact of market-maker concentration on adverse selection costs for NASDAQ stocks. The Journal of Financial Research, 28, 461–485.

Verrecchia, R. E. (1983). Discretionary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 5, 179–194.

Zhang, H., & Zheng, L. (2011). The valuation impact of reconciling pro forma earnings to GAAP earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 51, 186–202.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ted Christensen and Erv Black for sharing their pro forma earnings data. We also thank Richard Sloan (the editor), two anonymous reviewers, Nerissa Brown, Ted Christensen, David Dubofsky, Mary Stanford, and Marilyn Wiley for their valuable comments. Finally, we also want to thank participants at the University of Texas – Arlington workshop and the 2013 American Accounting Association FARS mid-year meeting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Lin et al. (1995) Model

Lin et al.’s (1995) and Masson’s (1993) models show how quote revisions following stock trades can be used to estimate the adverse-selection component of the bid-ask spread. In response to a sell (buy) order that reveals possible private information, the market maker adjusts the bid-ask midpoint downward (upward). In the Lin et al.’s model,Footnote 13 bid-quote and ask-quote revisions (B k+1 − B k , and A k+1 − A k, respectively) for a trade at time k are related to adverse selection expressed as a proportion (λk) of the signed one-half effective spread (Z k ), as shown in (5), (6), and (7).

where B is the bid quote, A is the ask quote, P is the transaction price, MP is the quote midpoint, Z is the signed one-half effective spread that takes a negative value for sell orders and a positive value for buy orders, and λ is the adverse-selection component as a fraction of Z, where 0 < λ < 1. In this model, the midpoint revision and the effective spreadFootnote 14 relate to the adverse-selection component λ as follows:

We begin by estimating the adverse-selection component (λ) of the effective spread on a daily basis using all N trades for a firm i during day j. We use ordinary least squares regression to estimate λij as follows:

where ln(MP) is the natural log of the quoted midpoint of the bid-ask spread, calculated as (bid + ask)/2; ADV is the regression estimate of λ, lnZ is the effective half spread, calculated as the natural log of price minus the natural log of quoted midpoint; and ε is the normally distributed random error term. From an economic perspective, ADV ij is the adverse-selection cost as a proportion of the effective spread for firm i for day j.

We find the daily adverse-selection cost (cents per share) as ASC ij = ADV ij × ESPREAD ij × 100, where ESPREAD ij is the average effective spread over all N trades for firm i in day j. Specifically, \( ESPREAD_{ij} = \mathop \sum \limits_{n = 1}^{N} \left( {|PRICE_{nij} - \, MIDPOINT_{nij} | \times 2} \right)/N_{ij} \). For each earnings announcement, the pre- and post-announcement estimates of adverse-selection cost, ASCpre it and ASCpost it, are daily adverse-selection cost averaged over the respective 10-day pre- and post-announcement windows for quarter t.

Appendix 2: Barron et al. (1998) model

To control for the uncertainty of a firm’s information environment, we rely on the Barron et al. (1998) model. In this model, the uncertainty in analyst k’s forecast for firm i in quarter t (V itk ) has two components: information uncertainty that is unique to analyst k’s private information set with respect to firm i’s earnings (D itk or idiosyncratic uncertainty) and information uncertainty that is inherent to shared public information about firm i (C it or common uncertainty). V itk is an ex ante concept that represents analyst k’s assessment of the expected variance of EPS it , conditional on the uncertainty of public information (an expectation shared by all analysts) and the uncertainty of private information (an expectation unique to analyst k).

On an ex post basis, we derive unbiased estimates of the expected values for D, C, and V for firm i in quarter t from three observable variables: analyst earnings per share forecasts (F ikt ), actual earnings per share (EPS it ), and the number of forecasts (N it ). The estimating equations are:

where D it is the dispersion in forecasts that depends on analysts’ reliance on noisy private information, C it is the common forecast error that depends on analysts’ reliance on noisy public information, and V it is the total information uncertainty about earnings. V it represents private and public information uncertainty averaged across all N it analysts. V it is distinct from, although clearly related to, uncertainty about the intrinsic value of firm i conditional on investors’ information set. The inverse of V it represents the precision of earnings information.

Appendix 3: Variable definitions

Variable used in pre- or post-announcement OLS models or treatment-effect outcome modelsa | |

|---|---|

ASCb | Adverse-selection cost in cents per share, found as ADV × ESPREAD × 100. |

ESPREADb | Mean daily effective spread measured as the absolute difference between quoted midpoint and transaction prices. |

ADV b | Mean daily adverse-selection component of the bid-ask spread, using the model in Lin et al. (1995). |

STREETt | An indicator variable equal to 1 when I/B/E/S reports street earnings and 0 otherwise. Street earnings is indicated when I/B/E/S actual EPS (VALUE) differs from GAAP EPS. For analysts, GAAP EPS is diluted EPS (epsfxq) or basic EPS (epspxq), consistent with the I/B/E/S variable FDI. We obtain I/B/E/S data from its unadjusted earnings per share files to avoid potential problems that stem from rounding effects that compromise the accuracy of the I/B/E/S split-adjusted EPS files (Payne and Thomas 2003; Philbrick and Ricks 1991). We correct I/B/E/S unadjusted data when a stock-split date occurs after the date of a forecast and before earnings are released (Glushkov and Robinson 2006), such that I/B/E/S EPS data (forecast and actual) reflect the actual number of shares outstanding as of the end of the fiscal quarter, consistent with Compustat. |

PROFORMAt | An indicator variable equal to 1 when the firm reports pro forma earnings and 0 otherwise. Pro forma earnings is indicated when management reports an earnings number that differs from GAAP EPS. For the manager, GAAP EPS is Compustat’s diluted EPS (epsfxq). |

NonGAAPt | An indicator variable equal to STREETt for the analysis of analysts’ reporting choices and PROFORMAt for managers’ reporting choices. |

ProbNonGAAPt | Probability of street earnings for analysts (ProbSTREETt) and the probability of pro forma earnings for managers (ProbPROFORMAt), estimated separately for analysts and managers, using a logistic regression model with the covariates discussed in Sect. 4.5.1. |

Dt | Dispersion in analyst earnings forecasts, representing the uncertainty in analysts’ private information in the Barron et al. (1998) model. Forecast dispersion is estimated using the last earnings forecast for quarter t by each of N analysts as reported in the I/B/E/S detailed earnings forecast database. We require at least three analysts for firm i in quarter t. |

Ct | Forecast error, representing the uncertainty in public information about earnings in the Barron et al. (1998) model. Ct uses the same earnings forecasts as Dt and the corresponding I/B/E/S actual EPS. We require at least three analysts for firm i in quarter t. |

Vt | Total forecast uncertainty over all N analysts, representing private and public uncertainty with respect to earnings information in the Barron et al. (1998) model. |

MIDPOINTb | Average daily midpoint of bid-ask spread. |

TradeSizeb | Average trade size (number of shares) per transaction. |

TradeFreqb | Average number of daily transactions. |

MV | Market value of equity (prccq × cshoq) at the end of quarter t. |

ANALYSTS | Number of analysts providing earnings forecasts (I/B/E/S item, NUMEST). |

BTM | Book-to-market ratio (ceqq/MV) at the end of quarter t. |

MBE | An indicator variable equal to 1 if I/B/E/S (manager) actual EPS met or exceed analysts’ median forecast and 0 otherwise. |

BEAT | An indicator variable equal to 1 if I/B/E/S (manager) FE is positive and 0 otherwise. |

MISS | An indicator variable equal to 1 if I/B/E/S (manager) FE is negative and 0 otherwise. |

MBECQ ct−1 | The number of consecutive quarters a firm met or beat (failed to meet) analysts’ median estimate based on I/B/E/S actual EPS (VALUE) less the median estimate (MEDEST). See footnote to this table for details. |

LOSS | Indicator variable equal to 1 if I/B/E/S median earnings estimate is negative. |

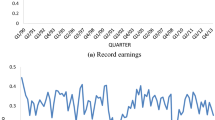

DEC | Indicator variable equal to 0 for any quarter when the earnings announcement date (rdq) occurred before the midpoint (March 31, 2001) of the March 21 to April 9, 2001, phase-in of decimalization of NASDAQ quotes and 1 otherwise. |

REGFD | Indicator variable equal to 0 for any quarter where the earnings announcement date (rdq) occurred before the compliance date (October 24, 2000) of Regulation FD and 1 otherwise. |

REGG | Indicator variable equal to 0 for any quarter when the earnings announcement date (rdq) occurred before the compliance date (March 29, 2003) of Regulation G and 1 otherwise. |

Variables used exclusively in post-announcement OLS models or treatment-effect outcome models | |

|---|---|

EX | Street (pro forma) EPS for the analysts (managers) minus GAAP EPS. EX is in dollars per share and is equal to 0 when STREET (PROFORMA) is equal to 0. |

absFE | The absolute value of FE. |

absFEs | absFE as a percentage of end-of-quarter share price; absFEs = (absFE/prccq) × 100. |

LOSS2 | An indicator variable equal to 1 if actual earnings reported by I/B/E/S (manager) is negative for analysts (managers). |

absEX | The absolute value of EX. |

absEXs | absEX as a percentage of end of quarter share price (prccq); absEXs = (absEX/prccq) × 100. |

RANKabsEXs | Ranked values of absEXs. Firms are grouped into percentiles to form rankings from 0 to 99, separately for the analysts and managers. |

FE | The forecast error is found as I/B/E/S actual EPS less the median estimate (FE = VALUE − MEDEST) for analysts and managers, unless PROFORMA = 1. Then, for managers only, FE = manager reported pro forma earnings – MEDEST. |

FE_FLIPS | An indicator variable equal to 1 if the FE > 0 and FE − EX < 0 and zero otherwise. FE_FLIPS is found separately for analysts and managers. FE_FLIPS is equal to 1 when income-increasing exclusions flipped the sign of the forecast error from miss to meet or beat analysts’ median estimate. |

Variable used exclusively in probit/selection modelsa | |

|---|---|

SALESGROWTHe | Sales growth for quarter t, found as (saleq t /saleq t−4) − 1. |

STDDEVROAe | Standard deviation of return on assets (roa = niq/atq) over the previous eight quarters. |

SPECITEMS | Indicator variable equal to 1 if firm reports a nonzero special item (spiq) and 0 otherwise. |

lnTA | Log of total assets (at) at the end of quarter t. |

SOX | Indicator variable equal to 1 for all calendar quarters ending after the second calendar quarter of 2002 and 0 otherwise. |

NQ dt | The number of consecutive quarters that I/B/E/S reported an earnings number that differs from GAAP earnings. |

GQ dt | The number of consecutive quarters that I/B/E/S reported an earnings that is the same as GAAP earnings. |

INTANGIBLESe | End-of-quarter intangible assets (intanoq) divided by total assets (atq). |

MTBe | End-of-quarter market value (prccq × cshoq) divided by book value of common equity (ceqq). |

LEVERAGEe | End-of-quarter total liabilities (ltq) divided by total common equity (ceqq). |

negOPFE | Indicator variable equal to1 if operating EPS (oepsxq) is less than the median I/B/E/S forecast and 0 otherwise. |

OPLOSS | Indicator variable equal to 1 if firm has an operating loss (oepsxq < 0) and 0 otherwise. |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Q., Skantz, T.R. The informativeness of pro forma and street earnings: an examination of information asymmetry around earnings announcements. Rev Account Stud 21, 198–250 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9345-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9345-8

Keywords

- Information asymmetry

- Pro forma earnings

- Street earnings

- Non-GAAP earnings

- Adverse selection

- Earnings precision