Abstract

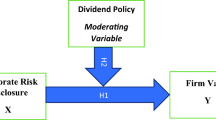

This paper investigates whether the desire to achieve higher equity valuations induces conglomerates to manipulate their segment earnings. I extend the Stein (Q J Econ 104:655–669, 1989) model to a multi-segment setting and show that conglomerates have incentives to transfer profits from segments operating in industries with lower valuation multiples to those with higher multiples, even if the market is not fooled in equilibrium. If companies engage in such manipulation, segments with relatively high (low) valuations should report abnormally high (low) profits. The empirical tests confirm this prediction and further show that the relation is stronger for firms with more dispersed segment valuations. This paper also demonstrates that the simple sum-of-the-parts valuation with multiples tends to overestimate the enterprise values for conglomerates and that the measurement errors increase with segment valuation dispersion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A recent Wall Street Journal article, published on November 20, 2012, provides anecdotal evidence of such a profit transfer. As summarized in the article, Hewlett-Packard accused Autonomy, a UK software maker that the company acquired in October 2011, of mischaracterizing some low-margin (and low-valuation) hardware sales as (high-margin and high-valuation) software sales. H-P said that the company was misled and overpaid for the acquisition. The revenue misclassification, together with several other alleged accounting irregularities, contributed more than $5 billion to an $8.8 billion write-down on the acquisition.

In fact, the new rule of SFAS 131 does not even define the measure of profit or loss to be disclosed. Instead, it allows any measure used for internal decision-making to be reported as segment profits. If managers abuse the flexibility to manipulate segment earnings, the quality of segment earnings could even be worse under SFAS 131.

We assume that the economic earnings for two segments have the same mean and precision for the sake of simplicity. Relaxing the assumption does not change the propositions or implications derived from the model.

I also tried to use segment identifiable assets as an alternative-weighting variable. The results were similar, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

I use the average absolute deviation instead of the standard deviation because the former measures are less influenced by outliers.

The detailed procedures to calculate IV can be found in Berger and Ofek (1995), p. 60.

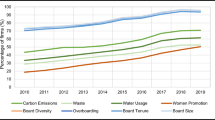

The relatively short sample period may account for the low statistical significance. The sample period covers 10 years between 1998 and 2007. The t-statistics with Newey–West correction for serial correlations for a time-series of 10 observations may lack the statistical power needed to show high significance.

Following Berger and Ofek (1995), I drop OPMG in the regression with EXV calculated from the earnings multiples to avoid spurious inferences.

However, I do not predict the measurement error problem to be the only or complete explanation for the diversification discounts. In reality, both the measurement error problem and the agency problem may co-exist, and both may contribute to the diversification discount. In fact, the results show that inter-segment profit transfer is unlikely to be a complete explanation for the diversification discounts because (1) the diversification discount remains noticeable, albeit low, for firms with low (or zero) segment valuation dispersion, and (2) the imputed values calculated from segment assets and the corresponding assets multiples are also higher than the market values, on average. Unless one can argue that the reported segment assets are subject to similar manipulations, one cannot attribute the discounts to measurement errors in the reported segment earnings or sales.

I appreciate the anonymous referee for pointing this out.

A detailed explanation of the estimation approach can be found in Appendix A of Core and Guay (2002), p. 629.

References

Baldwin, B. A. (1984). Segment earnings disclosure and the ability of security analysts to forecast earnings per share. The Accounting Review, 59(3), 376–389.

Bens, D. A., & Monahan, S. J. (2004). Disclosure quality and the excess value of diversification. Journal of Accounting Research, 42(4), 691–730.

Berger, P. G., & Hann, R. (2003). The impact of SFAS No. 131 on information and monitoring. Journal of Accounting Research, 41(2), 163–223.

Berger, P. G., & Hann, R. (2007). Segment profitability and the proprietary and agency costs of disclosure. The Accounting Review, 82, 869–906.

Berger, P. G., & Ofek, E. (1995). Diversification’s effect on firm value. Journal of Financial Economics, 37(1), 39–65.

Billett, M. T., & Mauer, D. C. (2003). Cross-subsidies, external financing constraints, and the contribution of the internal capital market to firm value. Review of Financial Studies, 16(4), 1167–1201.

Bradshaw, M. T. (2004). How do analysts use their earnings forecasts in generating stock recommendations? Accounting Review, 79(1), 25–50.

Buzzell, R. D., Gale, B. T., & Sultan, R. G. M. (1975). Market share: A key to profitability. Harvard Business Review, 53(1), 97–106.

Chen, P. F., & Zhang, G. (2003). Heterogeneous investment opportunities in multiple-segment firms and the incremental value relevance of segment accounting data. The Accounting Review, 78(2), 397–428.

Chen, P. F., & Zhang, G. (2007). Segment profitability, misvaluation and corporate divestment. The Accounting Review, 82(1), 1–26.

Core, J., & Guay, W. (2002). Estimating the value of employee stock option portfolios and their sensitivities to price and volatility. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(2), 613–630.

DeAngelo, L. E. (1986). Accounting numbers as market valuation substitutes: A study of management buyouts of public stockholders. The Accounting Review, 61(2), 400–420.

Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R. G., & Sweeney, A. P. (1995). Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review, 70(2), 193–225.

Denis, D. J., Denis, D. K., & Sarin, A. (1997). Agency problems, equity ownership, and corporate diversification. The Journal of Finance, 52(1), 135–160.

Denis, D. J., Denis, D. K., & Yost, K. (2002). Global diversification, and firm value. Journal of Finance, 57, 1951–1979.

Erickson, M., & Wang, S. (1999). Earnings management by acquiring firms in stock for stock mergers. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 27, 149–176.

Ettredge, M. L., Kwon, S. Y., Smith, D. B., & Zarowin, P. A. (2005). The impact of SFAS No. 131 business segment data on the market’s ability to anticipate future earnings. The Accounting Review, 80(3), 773–804.

Fan, Q. (2007). Earnings management and ownership retention for initial public offering firms: Theory and evidence. The Accounting Review, 82(1), 27–64.

Givoly, D., Hayn, C., & D’Souza, J. (1999). Measurement errors and information content of segment reporting. Review of Accounting Studies, 4, 15–43.

Hann, R. N. & Yu, Y. Y. (2009). Earnings management at the segment level. Marshall School of Business Working paper No. MKT 04-09.

Harris, M. S. (1998). The association between competition and managers’ business segment reporting decisions. Journal of Accounting Research, 36, 111–128.

Hoechle, D., Schmid, M., Walter, I., & Yermack, D. (2012). How much of the diversification discount can be explained by poor corporate governance? Journal of Financial Economics, 103, 41–60.

Holmstrom, B. (1979). Moral hazard and observability. Bell Journal of Economics, 10, 74–91.

Jensen, M. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. American Economic Review, 76, 323–329.

Jensen, M., & Murphy, K. (1990). Performance pay and top management incentives. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 225–263.

Jones, Jennifer J. (1991). Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research, 29(2), 193–228.

Lang, L. H. P., & Stulz, R. M. (1994). Tobin’s q, corporate diversification, and firm performance. Journal of Political Economy, 102(6), 1248–1280.

Lins, K., & Servaes, H. (1999). International evidence on the value of corporate diversification. The Journal of Finance, 54(6), 2215–2239.

Liu, J., Nissim, D., & Thomas, J. (2002). Equity valuation using multiples. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1), 135–162.

Lyandres, Evgeny. (2007). Strategic cost of diversification. Review of Financial Studies, 20(6), 1901–1940.

Newey, W. K., & West, K. D. (1987). A simple positive-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica, 55, 703–708.

Ozbas, O., & Scharfstein, D. (2010). Evidence on the dark side of internal capital markets. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 581–599.

Pollak, A., & Chin D. (2011). News Corporation 2Q11 Preview—First Published 21 December 2010, Macquarie Equities Research, 20 January 2011.

Prescott, J. E., Kohli, A. K., & Venkatraman, N. (1986). The market share-profitability relationship: An empirical assessment of major assertions and contradictions. Strategic Management Journal, 7, 377–394.

Rajan, R., Servaes, H., & Zingales, H. (2000). The cost of diversity: The diversification discount and inefficient investment. The Journal of Finance, 55(1), 35–80.

Scharfstein, D., & Stein, J. (2000). The dark side of internal capital markets: Divisional rent-seeking and inefficient investment. Journal of Finance, 55, 2537–2564.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1989). Management entrenchment. Journal of Financial Economics, 25, 123–139.

Stein, J. C. (1989). Efficient capital markets, inefficient firms: A model of myopic corporate behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 655–669.

Swaminathan, S. (1991). The impact of SEC mandated segment data on price variability and divergence of beliefs. The Accounting Review, 66(1), 23–41.

Teoh, S. H., Welch, I., & Wong, T. J. (1998a). Earnings management and the long-run market performance of initial public offerings. The Journal of Finance, 53(6), 1935–1974.

Teoh, S. H., Welch, I., & Wong, T. J. (1998b). Earnings management and the underperformance of seasoned equity offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 50, 63–99.

Teoh, S. H., Wong, T. J., & Rao, G. R. (1998c). Are accruals during initial public offerings opportunistic? Review of Accounting Studies, 3(1–2), 175–208.

Tusa, C. S., Pierson D., Mammola P., & Vora J. P. (2011). The 2nd coming of GE: Death of a financial, rebirth of a late cycle industrial. J. P. Morgan North America Equity Research, 24 January 2011.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for comments from Ashiq Ali, Sudipto Basu, Phil Berger, Kevin Chen, Peter Chen, Xia Chen, Qiang Cheng, Sung Gon Chung, John Core, Mark DeFond, Gerry Garvey, Rebecca Hann, Allen Huang, S.P. Kothari, Ryan LaFond, Charles Lee, Jim Ohlson, Panos Patatoukas, David Reeb, Zvi Singer, Richard Sloan, Rodrigo Verdi, Frank Yu, Amy Zang, Guochang Zhang, Weining Zhang, and seminar participants at the FARS 2013 Midyear Meeting, the Five Star Finance Forum at the Renmin University of China, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, Singapore Management University, UC Berkeley, and the University of Hong Kong. All errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix I: Excerpt from a research report for News corporation by Pollak and Chin (2011)

Appendix II: excerpt from a research report for General Electronics by Tusa et al. (2011)

Appendix III: variable definitions

- ABROA s,t :

-

Abnormal return on assets, calculated as (ROA s,t − IROA s,t ) − (\( \sum\limits_{s} \) (ROA s,t − IROA s,t ))/S. Return on assets, ROA s,t is the ratio of operating income after depreciation and amortization to identifiable assets, multiplied by 100 for segment s at year t. IROA s,t is the median ROA of all single-segment firms with the same three-digit SIC code as segment s in fiscal year t. S is the total number of segments of the firm

- ABINV s,t :

-

Abnormal investment, calculated as (INV s,t − IINV s,t ) − (\( \sum\limits_{s} \) (INV s,t − IINV s,t )/S), where INV s,t is the ratio of segment capital expenditure to identifiable assets, multiplied by 100. IINV s,t is the median ratio of capital expenditure to total assets of all single-segment firms in the same SIC three-digit industry in year t

- BM t :

-

Book-to-market ratio at the beginning of year t

- CAPEX t :

-

Capital expenditure in year t divided by net sales

- EXV t :

-

The logarithm of the discount of the market value (MV) of a firm relative to the imputed value (IV), log (MV/IV), where MV is the market value of the firm (EV), calculated as the sum of the market cap of equity, long-term debt, short-term debt, and preferred stock. IV is the imputed value of a firm, calculated as the sum of the imputed segment values, i.e., \( \sum\limits_{s} \) (VM s,t *AI s,t ). VM s,t is the median valuation multiples of all single-segment firms in the same industry, and AI s,t is the accounting variable of interest for segment s. Following Berger and Ofek, I calculate three EXV measures EXV_S, EXV_A, and EXV_E, which are estimated from sales, assets, and EBIT multiples, respectively. The sales multiple is calculated as the ratio of the EV to net sales; the EBIT multiple is calculated as the ratio of the EV to earnings before interest and taxes; and the assets multiple is calculated as the ratio of the EV to total assets

- HINDX s,t :

-

The Herfindahl index for the industry to which the segment belongs, where the industry is defined with a three-digit SIC code

- LEV t :

-

Long-term debt divided by the sum of long-term debt and the market value of equity

- LOGASSET t :

-

Logarithm of the firm’s total assets in millions

- MKTSHR s,t :

-

Market share, calculated as the sales of segment s as a fraction of the total sales of all firms/segments with the same three-digit SIC code

- NSEG t :

-

Logarithm of the number of segments reported by a firm

- OPMG t :

-

Operating margin, calculated as EBIT divided by net sales

- RELSIZE s,t :

-

The ratio of segment assets to firm assets at year t

- RELATED t :

-

The relatedness of a firm’s operations, which is equal to the difference between the total number of reported segments and the number of segments with different two-digit SIC codes

- RV s,t :

-

Relative sales/EBIT/EBITDA multiples, calculated as the valuation multiples of segment s, minus the sales-weighted valuation multiples of all segments of the firm, i.e., RV s,t = VM s,t − \( \sum\limits_{s} \)(VM s,t * ω s,t ). ω s,t is the weight of the segment sales as a fraction of the firm’s total sales, i.e., ω s,t = Sales s,t /(\( \sum\limits_{s} \) Sales s,t ). VM s,t is the median valuation multiples of all single-segment firms with the same three-digit SIC code as the segment. I examine three valuation multiples: the sales multiple (the ratio of the EV to net sales), the EBIT multiple (the ratio of the EV to earnings before interest and taxes), and the EBITDA multiple (the ratio of the EV to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). The EV is defined as the sum of the market cap of equity, long-term debt, short-term debt, and preferred stock

- SRV s,t :

-

The sign of RV s,t , which takes the value of 1 if RV s,t > 0, 0 if RV s,t = 0, and −1 if RV s,t < 0

- SIZE t :

-

Logarithm of the market cap. It is the logarithm of the firm’s market capitalization as of the beginning of fiscal year t

- VDISP t :

-

Dispersion of the sales/EBIT/EBITDA multiples, the normalized dispersion of the relative valuation multiples, calculated as VDISP t = \( \sum\limits_{s} \)(|RV s,t | * ω s,t )/\( \sum\limits_{s} \)(VM s,t * ω s,t ), where ω s,t is the weight of segment sales as a fraction of firm total sales, i.e., ω s,t = Sales s,t /(\( \sum\limits_{s} \) Sales s,t )

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

You, H. Valuation-driven profit transfer among corporate segments. Rev Account Stud 19, 805–838 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9264-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9264-5