Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to assess the impact of response option order and question order on the distribution of responses to the self-rated health (SRH) question and the relationship between SRH and other health-related measures.

Methods

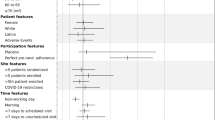

In an online panel survey, we implement a 2-by-2 between-subjects factorial experiment, manipulating the following levels of each factor: (1) order of response options (“excellent” to “poor” versus “poor” to “excellent”) and (2) order of SRH item (either preceding or following the administration of domain-specific health items). We use Chi-square difference tests, polychoric correlations, and differences in means and proportions to evaluate the effect of the experimental treatments on SRH responses and the relationship between SRH and other health measures.

Results

Mean SRH is higher (better health) and proportion in “fair” or “poor” health lower when response options are ordered from “excellent” to “poor” and SRH is presented first compared to other experimental treatments. Presenting SRH after domain-specific health items increases its correlation with these items, particularly when response options are ordered “excellent” to “poor.” Among participants with the highest level of current health risks, SRH is worse when it is presented last versus first.

Conclusion

While more research on the presentation of SRH is needed across a range of surveys, we suggest that ordering response options from “poor” to “excellent” might reduce positive clustering. Given the question order effects found here, we suggest presenting SRH before domain-specific health items in order to increase inter-survey comparability, as domain-specific health items will vary across surveys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Question 2, about alcohol consumption, is excluded from the index of current health risks. This question was included as part of the corpus to prime respondents in the conditions in which SRH is presented last to think of a range of health behaviors, conditions, and limitations, but cannot be used to reliably estimate behavioral risk given that the complex relationship between alcohol consumption and health cannot be assessed without additional data on the number of alcoholic drinks consumed daily [28].

References

Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 21–37.

Schnittker, J., & Bacak, V. (2014). The increasing predictive validity of self-rated health. PLoS ONE, 9(1), e84933.

Benyamini, Y., Idler, E. L., Leventhal, H., & Leventhal, E. A. (2000). Positive affect and function as influences on self-assessments of health. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55(2), P107–P116.

Benyamini, Y., Leventhal, E. A., & Leventhal, H. (1999). Self-assessments of health. Research on Aging, 21(3), 477–500.

Benyamini, Y., Leventhal, E. A., & Leventhal, H. (2000). Gender differences in processing information for making self-assessments of health. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(3), 354–364.

Benyamini, Y., Leventhal, E. A., & Leventhal, H. (2003). Elderly people’s ratings of the importance of health-related factors to their self-assessments of health. Social Science and Medicine, 56(8), 1661–1667.

Canfield, B., Miller, K., Beatty, P., Whitaker, K., Calvillo, A., & Wilson, B. (2003). Adult questions on the health interview survey—results of cognitive testing interviews conducted April–May 2003. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Cognitive Methods Staff., pp. 1–41.

DeSalvo, K. B., Bloser, N., Reynolds, K., He, J., & Muntner, P. (2006). Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(3), 267–275.

Garbarski, D., Schaeffer, N. C., & Dykema, J. (2011). Are interactional behaviors exhibited when the self-reported health question is asked associated with health status? Social Science Research, 40(4), 1025–1036.

Groves, R. M., Fultz, F. N., & Martin, E. (1992). Direct questioning about comprehension in a survey setting. In J. M. Tanur (Ed.), Questions about questions: Inquiries into the cognitive bases of surveys (pp. 49–61). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Krause, N. M., & Jay, G. M. (1994). What do global self-rated health items measure? Medical Care, 32(9), 930–942.

Carp, F. M. (1974). Position effects on interview responses. Journal of Gerontology, 29(5), 581–587.

Chan, J. C. (1991). Response-order effects in Likert-type scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51(3), 531–540.

Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Response strategies for coping with the cognitive demands of attitude measures in surveys. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 5(3), 213–236.

Krosnick, J. A., & Alwin, D. F. (1987). An evaluation of a cognitive theory of response-order effects in survey measurement. Public Opinion Quarterly, 51(2), 201–219.

Sudman, S., & Bradburn, N. M. (1982). Asking questions. New Jersey: Jossey-Bass.

Means, B., Nigam, A., Zarrow, M., Loftus, E. F., & Donaldson, M. S. (1989). Autobiographical memory for health-related events. Cognition and Survey Research, 6, 2, DHHS (PHS) 89-1077, 6(2), 1–38.

Keller, S. D., & Ware, J. E. (1996). Questions and answers about SF-36 and SF-12. Medical Outcomes Trust Bulletin, 4(3), 1–13.

Lee, S., & Schwarz, N. (2014). Question context and priming meaning of health: Effect on differences in self-rated health between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. American Journal of Public Health, 104(1), 179–185.

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. A. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hopkins, D. J., & King, G. (2010). Improving anchoring vignettes designing surveys to correct interpersonal incomparability. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74(2), 201–222.

Tourangeau, R., Rasinski, K. A., & Bradburn, N. (1991). Measuring happiness in surveys: A test of the subtraction hypothesis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 55(2), 255–266.

Schwarz, N., Strack, F., & Mai, H.-P. (1991). Assimilation and contrast effects in part-whole question sequences: A conversational logic analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 55(1), 3–23.

Bowling, A., & Windsor, J. (2008). The effects of question order and response-choice on self-rated health status in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(1), 81–85.

Crossley, T. F., & Kennedy, S. (2002). The reliability of self-assessed health status. Journal of Health Economics, 21(4), 643–658.

Lee, S., & Grant, D. (2009). The effect of question order on self-rated general health status in a multilingual survey context. American Journal of Epidemiology, 169(12), 1525–1530.

Callegaro, M., & DiSogra, C. (2008). Computing response metrics for online panels. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(5), 1008–1032.

National Institute on Alcohol, A., & Alcoholism. (2007). Helping patients who drink too much. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Krosnick, J. A. (2012). Improving question design to maximize reliability and validity. Conference on the Future of Survey Research, Arlington, VA.

Perneger, T., Gayet-Ageron, A., Courvoisier, D., Agoritsas, T., & Cullati, S. (2013). Self-rated health: Analysis of distances and transitions between response options. Quality of Life Research, 22(10), 2761–2768.

Preacher, K. J. (2002). Calculation for the test of the difference between two independent correlation coefficients [computer software]. Available from http://quantpsy.org.

Holbrook, A. L., Krosnick, J. A., Carson, R. T., & Mitchell, R. C. (2000). Violating conversational conventions disrupts cognitive processing of attitude questions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36(5), 465–494.

Lee, S., Schwarz, N., & Goldstein, L. S. (2014). Culture-sensitive question order effects of self-rated health between older Hispanic and non-Hispanic adults in the United States. Journal of Aging and Health, 26(5), 860–883.

Bailis, D. S., Segall, A., & Chipperfield, J. G. (2003). Two views of self-rated general health status. Social Science and Medicine, 56(2), 203–217.

Huisman, M., & Deeg, D. J. H. (2010). A commentary on Marja Jylhä’s “What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model” (69:3, 2009, 307–316). Social Science and Medicine, 70(5), 652–654.

Jylhä, M. (2009). What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Social Science and Medicine, 69(3), 307–316.

Jylhä, M. (2010). Self-rated health between psychology and biology. A response to Huisman and Deeg. Social Science and Medicine, 70(5), 655–657.

Tourangeau, R., Couper, M. P., & Conrad, F. G. (2013). “Up means good”: The effect of screen position on evaluative ratings in web surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 77(S1), 69–88.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grants to the Center for Demography and Ecology (T32 HD007014) and the Health Disparities Research Scholars training program (T32 HD049302), and from core funding to the Center for Demography and Ecology (R24 HD047873) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The data used in this study were collected by GfK with funding from Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (NSF Grant SES-0818839, Jeremy Freese and James Druckman, Principal Investigators). This study was approved by the Social and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2014 meeting of the American Association for Public Opinion Research in Anaheim, CA. We thank conference participants and the peer reviewers for their insightful comments. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and any errors are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garbarski, D., Schaeffer, N.C. & Dykema, J. The effects of response option order and question order on self-rated health. Qual Life Res 24, 1443–1453 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0861-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0861-y