Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the dimensionality and measurement invariance of the aphasia communication outcome measure (ACOM), a self- and surrogate-reported measure of communicative functioning in aphasia.

Methods

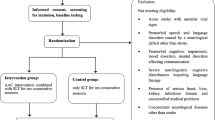

Responses to a large pool of items describing communication activities were collected from 133 community-dwelling persons with aphasia of ≥ 1 month post-onset and their associated surrogate respondents. These responses were evaluated using confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis. Chi-square difference tests of nested factor models were used to evaluate patient–surrogate measurement invariance and the equality of factor score means and variances. Association and agreement between self- and surrogate reports were examined using correlation and scatterplots of pairwise patient–surrogate differences.

Results

Three single-factor scales (Talking, Comprehension, and Writing) approximating patient–surrogate measurement invariance were identified. The variance of patient-reported scores on the Talking and Writing scales was higher than surrogate-reported variances on these scales. Correlations between self- and surrogate reports were moderate-to-strong, but there were significant disagreements in a substantial number of individual cases.

Conclusions

Despite minimal bias and relatively strong association, surrogate reports of communicative functioning in aphasia are not reliable substitutes for self-reports by persons with aphasia. Furthermore, although measurement invariance is necessary for direct comparison of self- and surrogate reports, the costs of obtaining invariance in terms of scale reliability and content validity may be substantial. Development of non-invariant self- and surrogate report scales may be preferable for some applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The term “proxy” has been used with two distinct meanings in the literature. Some authors have used the term to refer to a person close the patient who responds as he or she believes that the patient would respond [9, 16]. Others have used the term to refer to a person close to the patient who provides his or her own assessment, without considering how the patient might respond [12, 14]. In still other cases, the meaning is not clearly specified [13].

We use the term “surrogate” here to specify the second meaning of the word “proxy” discussed above in Footnote 1, i.e., a person close to the patient who provides his or her own assessment, without trying to respond as he or she thinks that the patient would respond.

The CFI and TLI are measures of incremental or relative fit that compare the tested model to a null model, which assumes that there are no relationships between any of the observed variables. They both adjust for model complexity, the CFI with an expression that subtracts the model degrees of freedom from the model Chi-square value, while the TLI is based on the ratio of the Chi-square to its degrees of freedom. CFI and TLI values of zero indicate worst possible fit, while values close to 1 indicate relatively good fit. The RMSEA is a badness-of-fit measure where a value of zero indicates best possible fit. It is based on the model Chi-square, its degrees of freedom, and the sample size. The WRMR is a newer statistic that measures the weighted average difference between the observed and model-estimated population variances and covariances.

Abbreviations

- ACOM:

-

Aphasia communication outcome measure

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- PWA:

-

Person with aphasia

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- SUR:

-

Surrogate

- TLI:

-

Tucker–Lewis index

- WRMR:

-

Weighted root mean square residual

References

Darley, F. L. (1982). Aphasia. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders.

Chapey, R., & Hallowell, B. (2001). Introduction to language intervention strategies in adult aphasia. In R. Chapey (Ed.), Language intervention strategies in aphasia and related neurogenic communication disorders (pp. 3–17). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Kauhanen, M. L., Korpelainen, J. T., Hiltunen, P., et al. (2000). Aphasia, depression, and non-verbal cognitive impairment in ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 10, 455–461.

Code, C. (2010). Aphasia. In J. S. Damico, N. Muller, & M. J. Ball (Eds.), The handbook of speech and language disorders (pp. 317–338). West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Williams, L. S., Weinberger, M., Harris, L. E., et al. (1999). Development of a stroke-specific quality of life scale. Stroke, 30, 1362–1369.

Duncan, P. W., Wallace, D., Lai, S. M., et al. (1999). The stroke impact scale version 2.0: Evaluation of reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. Stroke, 30, 2131–2140.

Doyle, P. J., McNeil, M. R., Mikolic, J. M., et al. (2004). The Burden of Stroke Scale (BOSS) provides valid and reliable score estimates of functioning and well-being in stroke survivors with and without communication disorders. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57, 997–1007.

Hilari, K., Byng, S., Lamping, D. L., et al. (2003). Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39 (SAQOL-39): evaluation of acceptability, reliability, and validity. Stroke, 34, 1944–1950.

Long, A., Hesketh, A., Paszek, G., et al. (2008). Development of a reliable self-report outcome measure for pragmatic trials of communication therapy following stroke: the Communication Outcome after Stroke (COAST) scale. Clinical Rehabilitation, 22, 1083–1094.

Chue, W. L., & Rose, M. L. (2010). The reliability of the Communication Disability Profile: A patient-reported outcome measure for aphasia. Aphasiology, 64, 940–956.

Glueckauf, R. L., Blonder, L. X., Ecklund-Johnson, E., et al. (2003). Functional outcome questionnaire for aphasia: Overview and preliminary psychometric evaluation. NeuroRehabilitation, 18, 281–290.

Paul, D. R., Fratalli, C. M., Holland, A. L., et al. (2004). Quality of communication life scale. Rockville, MD: The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Hilari, K., Owen, S., & Farrelly, S. J. (2007). Proxy and self-report agreement on the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 78, 1072–1075.

Cruice, M., Worrall, L., Hickson, L., et al. (2005). Measuring quality of life: Comparing family members’ and friends’ ratings with those of their aphasic partners. Aphasiology, 19, 111–129.

Hesketh, A., Long, A., & Bowen, A. (2010). Agreement on outcome: Speaker, carer, and therapist perspectives on functional communication after stroke. Aphasiology, 25, 291–308.

Duncan, P. W., Lai, S. M., Tyler, D., et al. (2002). Evaluation of proxy responses to the Stroke Impact Scale. Stroke, 33, 2593–2599.

Williams, L. S., Bakas, T., Brizendine, E., et al. (2006). How valid are family proxy assessments of stroke patients’ health-related quality of life? Stroke, 37, 2081–2085.

Sneeuw, K. C., Aaronson, N. K., de Haan, R. J., et al. (1997). Assessing quality of life after stroke. The value and limitations of proxy ratings. Stroke, 28, 1541–1549.

Rautakoski, P., Korpijaakko-Huuhka, A.-M., & Klippi, A. (2008). People with severe and moderate aphasia and their partners as estimators of communicative skills: A client-centred evaluation. Aphasiology, 22, 1269–1293.

Skolarus, L. E., Sanchez, B. N., Morgenstern, L. B., et al. (2010). Validity of proxies and correction for proxy use when evaluating social determinants of health in stroke patients. Stroke, 41, 510–515.

Doyle, P. J., McNeil, M. R., Hula, W. D., et al. (2003). The Burden of Stroke Scale (BOSS): Validating patient-reported communication difficulty and associated psychological distress in stroke survivors. Aphasiology, 17, 291–304.

Lomas, J., Pickard, L., Bester, S., et al. (1989). The communicative effectiveness index: Development and psychometric evaluation of a functional communication measure for adult aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 113–124.

Long, A., Hesketh, A., & Bowen, A. (2011). Communication outcome after stroke: A new measure of the carer’s perspective. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23, 846–856.

Meredith, W., & Teresi, J. A. (2006). An essay on measurement and factorial invariance. Medical Care, 44, S69–S77.

Meredith, W. (1993). Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika, 58, 525–543.

Borsboom, D. (2006). The attack of the psychometricians. Psychometrika, 71, 425–440.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–70.

Gregorich, S. E. (2006). Do self-report instruments allow meaningful comparisons across diverse population groups? Testing measurement invariance using the confirmatory factor analysis framework. Medical Care, 44, S78–S94.

Baas, K. D., Cramer, A. O., Koeter, M. W., et al. (2011). Measurement invariance with respect to ethnicity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Journal of Affective Disorders, 129, 229–235.

Sousa, R. M., Dewey, M. E., Acosta, D., et al. (2010). Measuring disability across cultures–the psychometric properties of the WHODAS II in older people from seven low- and middle-income countries. The 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based survey. International Journal of Methods Psychiatric Research, 19, 1–17.

Rivera-Medina, C. L., Caraballo, J. N., Rodriguez-Cordero, E. R., et al. (2010). Factor structure of the CES-D and measurement invariance across gender for low-income Puerto Ricans in a probability sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 398–408.

Heckman, B. D., Berlin, K. S., Watakakosol, R., et al. (2011). Psychosocial headache measures in Caucasian and African American headache patients: psychometric attributes and measurement invariance. Cephalalgia, 31, 222–234.

Coster, W. J., Haley, S. M., Ludlow, L. H., et al. (2004). Development of an applied cognition scale to measure rehabilitation outcomes. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85, 2030–2035.

Haley, S. M., Coster, W. J., Andres, P. L., et al. (2004). Activity outcome measurement for postacute care. Medical Care, 42, I49–I61.

Zhang, B., Fokkema, M., Cuijpers, P., et al. (2011). Measurement invariance of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D) among chinese and dutch elderly. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 74.

Taylor, M. L. (1965). A measurement of functional communication in aphasia. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 46, 101–107.

Blomert, L., Kean, M.-L., Koster, C., et al. (1994). Amsterdam-Nijmegen everyday language test: Construction, reliability and validity. Aphasiology, 8, 381–407.

Lincoln, N. B. (1982). The speech questionnaire: An assessment of functional langauge ability. International Rehabilitation Medicine, 4, 114–117.

Holland, A. L., Frattali, C., & Fromm, D. (1999). Communication activities of daily living (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Bayles, K. A., & Tomoeda, C. K. (1994). Functional linguistic communication inventory. Phoenix: Canyonlands.

Frattali, C. M., Thompson, C. K., Holland, A. L., et al. (1995). The Amercian Speech-Language-Hearing Association functional assessment of communication skills for adults (ASHA FACS). Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language Hearing Association.

Holland, A. L. (1980). Communicative activities in daily living. Baltimore: University Park Press.

Wirz, S., Skinner, C., & Dean, E. (1990). Revised Edinburgh Functional Communication Profile. Tucson, AZ: Communication Skill Builders.

Frattali, C. M. (1992). Functional assessment of communication: Merging public policy with clinical views. Aphasiology, 6, 63–83.

Doyle, P. J., McNeil, M. R., Le, K., et al. (2008). Measuring communicative functioning in community dwelling stroke survivors: Conceptual foundation and item development. Aphasiology, 22, 718–728.

Bayles, K. A., & Tomoeda, C. K. (1993). Arizona Battery for Communication Disorders of Dementia. Tucson, AZ: Canyonlands Publishing, Inc.

Sheikh, J. I., & Yesavage, J. A. (1986). Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) Recent Evidence and Development of a Shorter Version. In T. L. Brink (Ed.), Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention (pp. 165–173). New York: Hawthorn Press.

Porch, B. (2001). Porch index of communicative ability. Albuquerque, NM: PICA Programs.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Mplus User’s Guide (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

South, S. C., Krueger, R. F., & Iacono, W. G. (2009). Factorial Invariance of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale across Gender. Psychological Assessment, 21, 622–628.

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1986). Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet, 1, 307–310.

McHorney, C. A., & Fleishman, J. A. (2006). Assessing and understanding measurement equivalence in health outcome measures. Issues for further quantitative and qualitative inquiry. Medical Care, 44, S205–S210.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Doyle, P. J., Hula, W. D., McNeil, M. R., et al. (2005). An application of Rasch analysis to the measurement of communicative functioning. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 1412–1428.

Donovan, N. J., Rosenbek, J. C., Ketterson, T. U., et al. (2006). Adding meaning to measurement: Initial Rasch analysis of the ASHA FACS Social Communication Subtest. Aphasiology, 20, 362–373.

Rodriguez, A., Donovan, N. J, Velozo, C. A., et al. (2007) Measurement properties of the functional outcomes questionnaire for aphasia. Presented to the Clinical Aphasiology Conference, Scottsdale, AZ. Clinical Aphasiology Conference.

Schuell, H., Jenkins, J. J., & Carrol, J. B. (1962). A factor analysis of the Minnesota test for the differential diagnosis of aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 5, 350–369.

Clark, C., Crockett, D. J., & Klonoff, H. (1979). Factor analysis of the porch index of communication ability. Brain and Language, 7, 1–7.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Beth Friedman, Jessica Rapier, Mary Sullivan, Brooke Swoyer, Neil Szuminsky, and Sandra Wright.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doyle, P.J., Hula, W.D., Austermann Hula, S.N. et al. Self- and surrogate-reported communication functioning in aphasia. Qual Life Res 22, 957–967 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0224-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0224-5