Abstract

Purpose

To analyze changes in life satisfaction (LS) scores over time in persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) and to interpret what these changes mean.

Methods

Multicenter, prospective cohort study of persons with SCI (n = 96) classified into 3 life satisfaction trajectories identified earlier. Assessment took place 6 times from the start of active rehabilitation up to 5 years after discharge. Three LS scores were compared: (1) LS ‘now’ score, (2) ‘comparison’ score between LS ‘now’ and LS ‘before the SCI’, and (3) retrospective score of LS ‘before the SCI’.

Results

Persons in the low LS trajectory showed increase in the LS ‘now’ score, but not in the LS ‘comparison’ score and retrospective score. Persons in the recovery trajectory showed increase in the LS ‘now’ and LS ‘comparison’ scores, but not in the retrospective score. Persons in the high LS trajectory showed increase in the ‘comparison’ LS score and decrease in the retrospective score, but no change in the LS ‘now’ score.

Conclusions

Diverging patterns of change were found and that were interpreted as adaptation or scale recalibration. Recalibration could also be considered healthy rebalancing after SCI. Being able to compare different LS ratings can facilitate the interpretation of change in and stability of LS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Assessment of Quality of Life (QoL) is important in evaluating the impact of a spinal cord injury (SCI) on a person’s life. Different studies have investigated QoL after an SCI and yielded findings that were sometimes different from what was expected. For example, some studies found QoL scores in persons with SCI to be only slightly lower than QoL scores in the general population [1, 2]. Furthermore, QoL evaluations by persons with SCI themselves are considerably higher than those attributed to them by clinicians and significant others [3]. These findings raise questions about how QoL scores should be interpreted.

In recent years, response shift theory has been increasingly used to explain why high QoL scores are found in people with various conditions [4–12]. Response shift refers to a change in the meaning of one’s self-evaluation of QOL as a result of a change in internal standards (recalibration), values (reprioritization), or definition of QoL (reconceptualization) [4]. The suggestion is that patients try to make the best of their situation by coping, reframing, and rethinking their experiences and that this process results in different interpretations of QoL at different measurement moments [4, 10].

According to Sprangers and Schwartz [4], an important consequence of response shift is that it complicates ‘objective’ evaluation of QoL, because response shift can cause measurement bias. If a test or measurement is reliable, one usually assumes that the construct that is being assessed is stable and that a specific score refers to a specific response [4]. Response shift complicates such interpretation, due to recalibration, change in values, or reconceptualization of the concept QoL [4, 10]. In reaction, Ubel et al. [12] stated that, in the reasoning by Sprangers and Schwartz, the term response shift lumps together distinct phenomena that often have very different implications. More specifically, response shift refers to scale recalibration reflecting measurement bias in some situations, while it reflects mechanisms by which people adapt to changing health status and experience changes in their QoL in other situations [12]. To address this problem, Ubel et al. [12] suggested to abandon the term response shift and to specify whether changes in QoL over time are the result of (scale) recalibration and reflect measurement bias or are the result of true changes and refer to adaptation. Ubel et al. [12] did not define the term adaptation. In the present article, adaptation is defined as the healthy rebalancing by patients to their new circumstances [13].

We agree with Ubel et al. [12] that research in the field of changes in QoL would benefit from a better understanding of what a change in QoL over time means, which might also help clinicians to assist persons with SCI to adapt to having an SCI [11]. Data of a Dutch prospective cohort study [14], on which the present study is also based, showed that, for the study group as a whole, life satisfaction was low early after SCI but increased during and after inpatient rehabilitation [15–17]. Subsequent analysis revealed five distinct life satisfaction trajectories in the period between the start of active SCI rehabilitation and 5 years after discharge [18]. This finding shows that changes in life satisfaction scores did not occur in all persons with SCI and differed in pace and level between trajectories [18].

The aim of the present study was to analyze the longitudinal life satisfaction data of the Dutch prospective cohort study to understand what changes in life satisfaction over time actually mean. For this aim, different life satisfaction scores (a life satisfaction ‘now’ score, a ‘comparison’ score between life satisfaction ‘now’ and life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’, and a retrospective score of life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’) were compared, and assumptions were made whether changes in life satisfaction reflect adaptation or refer to scale recalibration. We assume that changes in life satisfaction refer to scale recalibration, if changes in the life satisfaction ‘now’ score are not compatible with changes in the ‘comparison’ score. Moreover, we assume that changes in the retrospective life satisfaction score over time refer to scale recalibration. Finally, we assume that adaptation occurs if both the life satisfaction ‘now’ score and the ‘comparison’ score increase in a similar way over time and if no changes in the retrospective score occur. In such situation, it is not likely that scale recalibration occurred.

Methods

Participants

This study is part of the Dutch research program ‘Restoration of mobility in spinal cord injury rehabilitation’ [14]. Subjects were admitted to inpatient rehabilitation in 1 of 8 Dutch rehabilitation centers specialized in SCI rehabilitation. Inclusion criteria were: (1) a recently acquired SCI; (2) age between 18 and 65 years; (3) grade A, B, C, or D on the American spinal injury association Impairment Scale (AIS); and (4) expected permanent wheelchair dependency. Participants were excluded if they had (1) an SCI caused by a malignant tumor, (2) a progressive disease, (3) psychiatric problems, or (4) insufficient command of the Dutch language to understand the goal of the study and test instructions. The research protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Rehabilitation Limburg/Institute for Rehabilitation Research and the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht. All persons gave written informed consent.

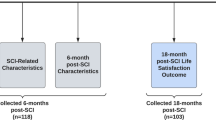

Procedure

Persons were assessed 6 times over the course of clinical inpatient rehabilitation and up to 5 years follow-up: at the start of active rehabilitation (defined as the time a person could sit for 3–4 h which was required to perform the physical tests that were part of the assessment), 3 months after the start of active rehabilitation, upon discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, and 1, 2, and 5 years after discharge. Each assessment consisted of a medical examination, an oral interview with a trained research assistant, and a self-report questionnaire. Questions about life satisfaction were part of the oral interview.

Instruments

Life satisfaction was operationalized as satisfaction with overall QoL and measured with two questions at each time point [16–19]. The first question (life satisfaction ‘now’) was: People can be more or less satisfied with their life as a whole, their so-called ‘quality of life’. What is your QoL at the moment? (1 = very unsatisfying, 2 = unsatisfying, 3 = somewhat unsatisfying, 4 = somewhat satisfying, 5 = satisfying, and 6 = very satisfying). The second question (life satisfaction ‘comparison’) was: If you compare your life now with your life before the SCI, is your QoL at the moment worse, equal or better than before the SCI? (1 = much worse, 2 = worse, 3 = somewhat worse, 4 = more or less equal, 5 = somewhat better, 6 = better, and 7 = much better). Evidence of construct validity of both questions according to established criteria [20] is provided by correlations from 0.62 up to 0.76 for the life satisfaction ‘now’ score, and from 0.58 up to 0.62 for the life satisfaction ‘comparison’ score with the Life Satisfaction Questionnaire (LiSat-9) [21] in our study sample. The LiSat-9 is a standardized questionnaire that consists of one item about satisfaction with life as a whole and eight items about satisfaction with life domains, e.g., vocational situation, leisure time activities, and family relationships. The LiSat-9 is a reliable, valid, and responsive measure of life satisfaction in persons with SCI [22].

At the first and the last assessment, an extra life satisfaction question was assessed. Participants were asked to retrospectively rate their life satisfaction before the SCI: If you look back at your life before the SCI, how would you rate your QoL before the SCI? (1 = very unsatisfying, 2 = unsatisfying, 3 = somewhat unsatisfying, 4 = somewhat satisfying, 5 = satisfying, and 6 = very satisfying). The rating on this question was called early retrospective score at the first assessment and late retrospective score at the last assessment.

Lesion characteristics were assessed according to the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury [23]. Neurological levels below T1 were defined as paraplegia, and neurological levels at or above T1 were defined as tetraplegia. AIS grades A and B were considered motor complete, and grades C and D were considered motor incomplete. Cause of injury was dichotomized in traumatic versus non-traumatic.

Demographic characteristics included were age, gender, educational level (low: no education or only vocational education, middle: high school, and high: bachelor/master), marital status (living together versus living alone), and having children (yes, no). All were measured at the start of active rehabilitation.

Statistical analyses

Only persons who completed at least the first and the last assessment were included in the analyses. A non-response analysis was performed by comparing persons who completed the assessment 5 years after discharge with persons who did not complete this assessment, using Chi-square tests and Mann–Whitney U tests.

Descriptive statistics were computed. Moreover, changes in different life satisfaction scores were tested using Wilcoxon tests. The life satisfaction ‘now’ score, the ‘comparison’ score between life satisfaction ‘now’ and life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’, and the early and late retrospective life satisfaction scores were compared with each other to indicate whether changes in life satisfaction reflect adaptation or refer to scale recalibration.

In the present study, three of the five life satisfaction trajectories, that were distinguished in an earlier study by fitting a latent class growth mixture model to the sum score of the life satisfaction ‘now’ score and the ‘comparison’ score [18], were used to form three mutually distinct subgroups. Persons in the low life satisfaction trajectory (low levels of life satisfaction at all time points), the recovery trajectory (steady improvements over time with low life satisfaction scores at the beginning and high life satisfaction scores at the end), and the high life satisfaction trajectory (initial high levels of life satisfaction with slight increments over time) were included. Persons in the deterioration trajectory (high life satisfaction score at the beginning and steep declines over time) were not included, because of the small number (n = 5) of respondents in this group. Furthermore, persons in the intermediate life satisfaction trajectory (n = 63) were also not included because this trajectory was less distinctive than the other three trajectories (higher and lower levels of life satisfaction between individuals balanced each other which resulted in a stable line over time).

SPSS statistical program for Windows (version 16.0) was used for the analyses. A Bonferroni correction was applied, because subgroup analyses were carried out. Significance was, therefore, set at a P value of less than 0.05/3 = 0.017.

Results

Respondent characteristics

For the present study, 206 persons completed the life satisfaction scores at the start of active rehabilitation, and 145 persons completed the life satisfaction scores at the first and last assessment. Of the 145 persons, 38 persons showed a low life satisfaction trajectory, 34 were in the recovery trajectory, and 24 showed a high life satisfaction trajectory. These 96 persons were included in the analyses. The other 49 persons were excluded from the analysis, because they were in the deterioration trajectory or in the less distinctive intermediate life satisfaction trajectory.

A comparison between participants and non-participants 5 years after discharge showed no differences between both groups except that non-participants had a higher proportion of non-traumatic SCI and were older than participants (Table 1). The median time between the onset of SCI and start of active rehabilitation was 75 days (interquartile range between 52 and 114 days) and the mean time was 94 SD 64 days.

Changes in life satisfaction scores over time

In Tables 2, 3 and Figs. 1, 2 changes in life satisfaction scores over time are shown. The persons in the low life satisfaction trajectory were characterized by a low life satisfaction ‘now’ score at the start of active rehabilitation which increased over time (P = 0.001). Five years after discharge, however, the mean life satisfaction ‘now’ score was still unsatisfying. The ‘comparison’ question showed that the experienced difference between life satisfaction ‘now’ and life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’ did not change over time (P = 0.234), nor did the early and late retrospective scores of life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’ (P = 0.531).

The persons in the recovery trajectory revealed a low life satisfaction ‘now’ score at the start of active rehabilitation, but this rating increased strongly over time (P = 0.000), and high life satisfaction ‘now’ scores were reported 5 years after discharge. The comparison between life satisfaction ‘now’ and life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’ also increased over time (P = 0.000). The retrospective score of life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’, however, did not change (P = 0.057).

The persons in the high life satisfaction trajectory were characterized by a high life satisfaction ‘now’ score at the start of active rehabilitation, which remained high over time (P = 0.049). The comparison question, however, increased over time (P = 0.000). Furthermore, the early retrospective life satisfaction score ‘before the SCI’ was higher than the late retrospective life satisfaction score 5 years after discharge (P = 0.006).

Discussion

The present study analyzed the longitudinal life satisfaction data of a prospective cohort study to improve the interpretation of changes in life satisfaction during inpatient rehabilitation and up to 5 years after discharge. We found differences between the three subgroups of persons with SCI with respect to changes in the different life satisfaction scores and in the interpretations of these changes.

Interpretation of changes in life satisfaction

In persons in the low life satisfaction trajectory, only the life satisfaction ‘now’ score improved, while the life satisfaction ‘comparison’ score and the retrospective life satisfaction score did not change. According to our assumptions, the change in the life satisfaction ‘now’ score refers to scale recalibration. We speculate that this might reflect a situation in which persons with SCI are reluctant to recognize improvement of their situation and keep referring to their loss of body function and thereby show resistance to adaptation to their situation [24]. Only considering life satisfaction ‘now’ would result in overestimation of adaptation to SCI in this group.

In contrast, in persons in the recovery trajectory, clear changes in the life satisfaction ‘now’ and ‘comparison’ score were reported over time. Scale recalibration is unlikely in this group, because both life satisfaction ratings increased, and the retrospective score of life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’ did not change. Therefore, data suggest that adaptation to having an SCI took place in persons in this trajectory.

The persons in the high life satisfaction trajectory formed a distinct subgroup, because the life satisfaction ‘now’ score did not change, while both the ‘comparison’ score and the retrospective life satisfaction score showed clear changes over time. This implies that life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’ was judged differently at different time points, suggesting scale recalibration. One could argue that this change might be the result of recall bias [12], due to a time span of more than 5 years. However, this explanation falls short because this change only occurred in the high life satisfaction trajectory. The life satisfaction ‘now’ score might also have been affected by a ceiling effect, because this score was already high at the start of active rehabilitation in this trajectory, but it appears to be not very useful to ask for satisfaction beyond ‘very satisfied’ just to increase the scale range. A better explanation might be that a change in internal standards has taken place which can result in high life satisfaction ratings despite severe differences in life circumstances. Again, only considering the life satisfaction ‘now’ score would have resulted in the wrong conclusion, because no change in this score was reported while changes in other life satisfaction scores were observed. The life satisfaction ‘now’ score, therefore, seems to underestimate adaptation to SCI in persons in the high life satisfaction trajectory. According to Ubel et al. [12], a change in internal standards caused by scale recalibration reflects measurement bias. However, based on our definition of adaptation, such a change in internal standards can also be considered a healthy rebalancing by patients to their new circumstances and, therefore, suggests adaptation instead of measurement bias. Carver and Scheier [25] described, using self-regulation theory, how persons who encounter a severe deterioration in their health might scale back their reference point against which they compare their current condition. An important consequence of such a shift in reference point is that the potential for experiencing positive affect increases and the potential for negative affect decreases, because with the adjusted reference point there is less room for failing to reach the reference standard and more room for exceeding it [25]. As a result, persons can have a good QoL in spite of severe deteriorations in health. Similarly, a case series provided examples of how persons adapt to changing conditions by reevaluating their own internal standards [11].

Interestingly, in all three trajectories, the early retrospective life satisfaction score was higher in comparison with life satisfaction scores in the general Dutch population (4.7) [2]. Suffering SCI seemed to induce scale recalibration of life satisfaction in all persons immediately after SCI. However, only in the high life satisfaction trajectory, the late retrospective life satisfaction score differed from the early retrospective life satisfaction score. We speculate that scale recalibration of life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’ occurred at two different moments in time. However, without pre-SCI life satisfaction data, this assumption cannot be tested.

Why should we use different life satisfaction ratings?

Our results showed that comparing different life satisfaction scores with each other is necessary to interpret changes in life satisfaction after the occurrence of a serious health condition. As shown, only considering life satisfaction ‘now’ scores can result in the wrong conclusions. In persons in the low life satisfaction trajectory, the life satisfaction ‘now’ score seemed to overestimate adaptation to SCI, while in persons in the high life satisfaction trajectory this score seemed to underestimate adaptation to SCI. The ‘comparison’ question might be a better indicator to measure adaptation, because changes in the comparison score were consistent with at least one other score in all trajectories. In persons in the low life satisfaction trajectory, this score did not change; while it changed in persons in the recovery trajectory and in the high life satisfaction trajectory. Because adaptation seemed to have only occurred in persons in the recovery trajectory and the high life satisfaction trajectory, a change in the comparison question might be a good indicator to measure adaptation.

In other longitudinal studies on life satisfaction in persons with SCI, only current life satisfaction was measured [26–29]. Using different life satisfaction ratings gives a more complete overview of how life satisfaction scores change in persons with SCI over time and how these scores can differ between persons with SCI.

Limitations

A limitation to the present study was that only persons with complete life satisfaction data at the start of active rehabilitation and 5 years after discharge in three of the five life satisfaction trajectories were included in the analyses. The non-response analysis, however, showed that no clear differences existed between participants and dropouts with respect to life satisfaction scores at the start of active rehabilitation. However, persons who were older and had a non-traumatic spinal cord injury had a higher chance of dropping out of the study, which might have led to patient selection bias. Further, persons who were in the deterioration trajectory and in the intermediate life satisfaction trajectory were not included in the analyses. This limits the degree to which the results could be generalized to the whole population of persons with SCI. Second, the life satisfaction ‘now’ score and the life satisfaction ‘comparison’ score showed construct validity, but evidence on other psychometric properties is lacking. We do not have psychometric statistics on the validity and reliability of the retrospective life satisfaction score because it is not relevant to compare the retrospective rating of life satisfaction before SCI to a measure of current life satisfaction. Third, although we tried to measure life satisfaction as soon as possible after the occurrence of SCI, on average, this rating took place 2 months after the SCI, so that some recovery in life satisfaction might have already occurred which could have influenced the early retrospective life satisfaction score. Fourth, a late retrospective life satisfaction score was only carried out 5 years after discharge. It would have been better to have a retrospective life satisfaction score at each measurement moment. Fifth, recall bias might have played a role. With passage of time, remembering how life satisfaction was before the SCI might have become more difficult. This could have influenced the interpretation of the comparison between life satisfaction ‘now’ and life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’, and the retrospective life satisfaction score 5 years after discharge. Sixth, we used very simple single item measures. Single items may have acceptable psychometric properties [30], but multi-item measures are preferred if feasible. Moreover, the life satisfaction items were of ordinal level, so that we could not use more sophisticated parametric statistics. Finally, we did not consider determinants of life satisfaction in this paper. Elsewhere though we showed that socio-demographic characteristics and SCI-characteristics were poor predictors of life satisfaction in this cohort [18], but that psychosocial factors were determinants of life satisfaction [17]. Further study, however, is needed to explain why different life satisfaction trajectories exist and if certain mechanisms of adaptation are specific for certain trajectories.

Future directions

Although many improvements can be made with respect to the design of the present study, this study offers some initial conclusions which are worthwhile to take into account in the design of future studies on life satisfaction and response shift. First of all, only considering life satisfaction ‘now’ scores can result in the wrong conclusions. Instead, comparing different life satisfaction ratings with each other is necessary to better interpret change in and stability of life satisfaction. The comparison question seems to be useful in addition to a life satisfaction ‘now’ score, and might be a better indicator to measure adaptation. This score also seems to be less susceptible to a ceiling effect than ratings of current life satisfaction. Secondly, unlike Ubel et al. [12], we do not consider scale recalibration as measurement bias. Analyzing scale recalibration may give insight into mechanisms of adaptation or resistance to adaptation, and by treating scale recalibration as measurement bias one neglects this part of the adaptation process. Like Carver and Scheier [25], we think that scale recalibration is one of the mechanisms which can explain how people are able to have a good QoL despite severe differences in life circumstances [25]. Further research is necessary to better understand individual differences in the ease or speed in which scale recalibration occurs.

For future studies we recommend to compare different life satisfaction ratings at different measurement time points to better understand what a change in life satisfaction over time means. Moreover, we recommend the subgroup approach that was used in the present study to examine whether or not certain mechanisms of adaptation are specific for persons in certain trajectories. Further, in case one wants to gain more insight into different mechanisms of adaptation, we recommend to use an interview-based questionnaire, like the Schedule for Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQoL) [31], which allows respondents to indicate the relative importance of different areas of life and can be used to measure reprioritization; or the Quality of Life Appraisal Profile [5], which assesses the personal meaning of QoL and can, therefore, be used to measure reconceptualization of QoL. Finally, although our simple measures and analyses already revealed some relevant insights, the use of validated multi-item measures in future studies is recommended. This would allow for more sophisticated statistical analyses [8, 32] to examine changes in QoL scores over time which were not possible in our study.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that adaptation to severe disability is a multi-faceted process that varies between subgroups. Adaptation seemed to have occurred among persons in the recovery and high life satisfaction trajectories, although this was reflected in different ways. Adaptation did not seem to occur in persons in the low life satisfaction trajectory. We feel that a change in the ‘comparison’ score between life satisfaction ‘now’ and life satisfaction ‘before the SCI’ is the best indicator to measure adaptation.

Abbreviations

- LS:

-

Life satisfaction

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SCI:

-

Spinal cord injury

- AIS:

-

American spinal injury association impairment scale

References

Dijkers, M. P. (1997). Quality of life after spinal cord injury: A meta analysis of the effects of disablement components. Spinal Cord, 35, 829–840.

Post, M. W., van Dijk, A. J., van Asbeck, F. W., & Schrijvers, A. J. (1998). Life satisfaction of persons with spinal cord injury compared to a population group. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 30, 23–30.

Bach, J. R., & Tilton, M. C. (1994). Life satisfaction and well-being measures in ventilator assisted individuals with traumatic tetraplegia. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 75(6), 626–632.

Sprangers, M. A., & Schwartz, C. E. (1999). Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: A theoretical model. Social Science and Medicine, 48, 1507–1515.

Rapkin, B. D., & Schwartz, C. E. (2004). Toward a theoretical model of quality-of-life appraisal: Implications of findings from studies of response shift. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2, 14.

Schwartz, C. E., Bode, R., Repucci, N., Becker, J., Sprangers, M. A., & Fayers, P. M. (2006). The clinical significance of adaptation to changing health: A meta-analysis of response shift. Quality of Life Research, 15, 1533–1550.

Visser, M. R., Oort, F. J., & Sprangers, M. A. (2005). Methods to detect response shift in quality of life data: A convergent validity study. Quality of Life Research, 14, 629–639.

Oort, F. J., Visser, M. R., & Sprangers, M. A. (2009). Formal definitions of measurement bias and explanation bias clarify measurement and conceptual perspectives on response shift. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1126–1137.

Schwartz, C. E., & Sprangers, M. A. (2009). Reflections on genes and sustainable change: Toward a trait and state conceptualization of response shift. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1118–1123.

Westerman, M. J., The, A. M., Sprangers, M. A., Groen, H. J., van der Wal, G., & Hak, T. (2007). Small-cell lung cancer patients are just ‘a little bit’ tired: Response shift and self-presentation in the measurement of fatigue. Quality of Life Research, 16(5), 853–861.

van Rijn, T. (2009). A physiatrist’s view of response shift. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1191–1195.

Ubel, P. A., Peeters, Y., & Smith, D. (2010). Abandoning the language of “response shift”: A plea for conceptual clarity in distinguishing scale recalibration from true changes in quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 19, 465–471.

de Ridder, D., Geenen, R., Kuijer, R., & van Middendorp, H. (2008). Psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Lancet, 372, 246–255.

de Groot, S., Dallmeijer, A. J., Post, M. W., van Asbeck, F. W., Nene, A. V., Angenot, E. L., et al. (2006). Demographics of the Dutch multicenter prospective cohort study “restoration of mobility in spinal cord injury rehabilitation”. Spinal Cord, 44, 668–675.

van Koppenhagen, C. F., Post, M. W., van der Woude, L. H., de Witte, L. P., van Asbeck, F. W., de Groot, S., et al. (2008). Changes and determinants of life satisfaction after spinal cord injury: A cohort study in The Netherlands. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 89(9), 1733–1740.

van Koppenhagen, C. F., Post, M. W., van der Woude, L. H., de Groot, S., de Witte, L. P., van Asbeck, F. W., et al. (2009). Recovery of life satisfaction in persons with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88, 887–895.

van Leeuwen, C. M., Post, M. W., van Asbeck, F. W., Bongers-Janssen, H. M., van der Woude, L. H., de Groot, S., et al. (2012). Life satisfaction in people with spinal cord injury during the first 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(1), 76–83.

van Leeuwen, C. M., Post, M. W., Hoekstra, T., van der Woude, L. H., de Groot, S., Snoek, G. J., et al. (2011). Trajectories in the course of life satisfaction after spinal cord injury: Identification and predictors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(2), 207–213.

van Leeuwen, C. M., Post, M. W., van Asbeck, F. W., van der Woude, L. H., de Groot, S., & Lindeman, E. (2010). Social support and life satisfaction in spinal cord injury during and up to 1 year after inpatient rehabilitation. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 42, 265–271.

Maynard, F. M., Jr., Bracken, M. B., Creasey, G., Ditunno, J. F., Jr., Donovan, W. H., Ducker, T. B., et al. (1997). International standards for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 35, 266–274.

Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., et al. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 34–42.

Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Eklund, M., & Fugl-Meyer, K. S. (1991). Vocational rehabilitation in northern Sweden. III. Aspects of life satisfaction. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 23(2), 83–87.

Post, M. W. (2010). Measuring the subjective appraisal of participation with life satisfaction measures: Bridging the gap between participation and quality of life measurement. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 15(4), 1–15.

Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist, 56(3), 239–249.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2000). Scaling back goals and recalibration of the affect system are processes in normal adaptive self-regulation: understanding ‘response shift’ phenomena. Social Science and Medicine, 50(12), 1715–1722.

Stensman, R. (1994). Adjustment to traumatic spinal cord injury: A longitudinal study of self-reported quality of life. Paraplegia, 32, 416–422.

Kennedy, P., & Rogers, B. A. (2000). Reported quality of life of people with spinal cord injuries: A longitudinal analysis of the first 6 months post-discharge. Spinal Cord, 38, 498–503.

Putzke, J. D., Barrett, J. J., Richards, J. S., Underhill, A. T., & Lobello, S. G. (2004). Life satisfaction following spinal cord injury: Long-term follow-up. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 27, 106–110.

Mortenson, W. B., Noreau, L., & Miller, W. C. (2010). The relationship between predictors of quality of life after spinal cord injury at 3 and 15 months after discharge. Spinal Cord, 48, 73–79.

de Boer, A. G., van Lanschot, J. J., Stalmeier, P. F., van Sandick, J. W., Hulscher, J. B., de Haes, J. C., et al. (2004). Is a single-item visual analogue scale as valid, reliable and responsive as multi-item scales in measuring quality of life? Quality of Life Research, 13(2), 311–320.

Joyce, C. R., Hickey, A., McGee, H. M., & O’Boyle, C. A. (2003). A theory-based method for the evaluation of individual quality of life: The SEIQoL. Quality of Life Research, 2(3), 275–280.

Mayo, N. E., Scott, S. C., Dendukuri, N., Ahmed, S., & Wood-Dauphinee, S. (2008). Identifying response shift statistically at the individual level. Quality of Life Research, 17(4), 627–639.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating Dutch rehabilitation centers, and the research assistants in these centers who collected all data: Rehabilitation Center De Hoogstraat (Utrecht), Reade, Centre for Rehabilitation and Rheumatology (Amsterdam), Rehabilitation Center Het Roessingh (Enschede), Adelante (Hoensbroek), Rehabilitation Center Sint Maartenskliniek (Nijmegen), Center for Rehabilitation—Location Beatrixoord (Haren), Rehabilitation Center Heliomare (Wijk aan Zee), and Rehabilitation Center Rijndam (Rotterdam). This study was supported by the Dutch Health Research and Development Council, ZON-MW Rehabilitation program, grant no. 1435.0003 and 1435.0025.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Leeuwen, C.M.C., Post, M.W.M., van der Woude, L.H.V. et al. Changes in life satisfaction in persons with spinal cord injury during and after inpatient rehabilitation: adaptation or measurement bias?. Qual Life Res 21, 1499–1508 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-0073-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-0073-7