Abstract

Objective

Type D personality has been associated with impaired health status in chronic heart failure (CHF), but other psychological factors may also be important.

Aim

To determine whether non-Type D patients with low positive affect and Type D patients report lower health status, compared with non-Type D patients with high positive affect at 12-month follow-up in chronic heart failure.

Methods

Consecutive CHF outpatients (n = 276) filled out the Short Form-12 (health status) and Health Complaints Scale (disease-specific complaints) at inclusion and 12-month follow-up, and the DS14 (Type D personality) and positive affect (Global Mood Scale) at inclusion. Three groups were composed: non-Type D patients without anhedonia, non-Type D patients with anhedonia, and Type D patients.

Results

After controlling for demographic and clinical confounders, and scores at inclusion, anhedonic non-Type D patients reported lower mental health status (β = –.19, P < .004), and more feelings of disability (β = .10, P = .04), marginally lower physical health status (β = −.11, P = .07), and equal levels of cardiac symptoms (β = .04, P = .43), when compared with non-Type D’s without anhedonia. Type D patients reported lower levels of impaired mental health status, more cardiac symptoms and feelings of disability (−.31 < β < .17, all Ps < .05). A trend was shown for physical health status (β = −.11, P = .09).

Conclusion

Non-Type D patients low on positive affect and Type D patients report lower levels of health status in CHF, compared with non-Type D patients with high positive affect. Future studies need to determine whether lack of positive affect is associated with impaired clinical outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychological risk factors have been acknowledged in the onset and progression of coronary heart disease (CHD) [1]. Apart from the established detrimental effects of negative emotions, there’s a growing interest in the role of positive affect [2]. Positive and negative affect can be considered as two independent systems, with positive affect not solely being the opposite of negative affect [3], and the possibility that both types of affect can be present simultaneously [4]. High positive affect can be described as a state of high energy, full concentration, and pleasurable engagement, whereas high negative affect can be described as the tendency to report distress, discomfort, dissatisfaction, and feelings of hopelessness over time and situations [5].

Positive affect has been shown to be protective for incident hypertension [6], whereas the influence on incident CHD is conflicting [7, 8]. In established CHD, high levels of positive affect have been associated with less hospital readmissions [9], whereas low levels of positive affect, also referred to as anhedonia, increase the risk of major clinical events in patients following coronary-artery stenting [10]. Conflicting findings have been reported for associations between positive affect and survival in CHD (e.g. [11–13]). Finally, positive affect has been shown to be associated with the production of early inflammatory markers in a middle-aged community sample [14], and systolic blood pressure in healthy non-smoking men [15].

In addition to positive affect, there is a growing interest in the role of personality factors in cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Type D personality (i.e., the combined tendency to experience negative emotions and to inhibit the expression of these emotions) is an emerging independent risk marker for clinical outcome and impaired patient-centred outcomes in cardiac disease (e.g., [16–18]). However, Type D personality is not the only risk marker for impaired health outcomes in CVD. Within those patients categorized as non-Type D, there may also be some heterogeneity in terms of their risk of adverse health outcomes. Within those patients categorized as having no Type D personality, some subgroups of patients may also report lower levels of health outcomes.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to determine whether non-Type D patients low on positive affect and Type D patients, report lower levels of health status when compared with non-Type D patients with high positive affect at 12-month follow-up in chronic heart failure (CHF).

Method

Patient selection and procedure

Consecutive heart failure outpatients (n = 408) were approached for participation by their treating cardiologist or specialised heart failure nurse between January 2001 and June 2007 at the outpatient clinics of the St. Elisabeth Hospital, Tilburg, and TweeSteden Hospital, Tilburg and Waalwijk, Tilburg, The Netherlands. Inclusion criteria consisted of (1) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40%, (2) age ≤ 80 years, and (3) no hospitalisations in the month prior to inclusion in the study. Patients were excluded from participation in case of (1) insufficient knowledge of written or spoken Dutch language, (2) evident cognitive impairments, (3) chronic severe psychiatric condition (except for depression or anxiety), and (4) presence of other life-threatening co-morbidities (e.g., cancer). All patients were treated according to the most recent guidelines for heart failure [19].

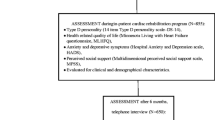

If patients agreed to participate, they were contacted by the researcher by telephone within 2 weeks after their outpatient visit. Patients filled out a set of standardized and validated questionnaires at inclusion and at 12-month follow-up at home and were asked to return the completed questionnaire in a stamped, pre-addressed envelope. Questionnaires were checked for completeness and in case items were left open, participants were called or mailed a copy of the questionnaires with the request to complete these. Patients who did not return the questionnaires within 2 weeks received a reminder telephone call or letter. A flow-chart of patient selection is provided in Fig. 1. The response rate was 67.4% and final analyses were based on 276 patients.

The study protocol was approved by the medical ethics committee of both teaching hospitals. Participation was voluntary. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration, and every patient provided written informed consent.

Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic variables included gender, age, educational level, and marital status, and were assessed by means of purpose designed questions in the questionnaire. Clinical variables, obtained from the patients’ medical records, consisted of LVEF, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, etiology of heart failure, current smoking status, cardiac history (i.e., previous myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)), history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and peripheral arterial disease (PAD). In addition, information on prescribed medications (i.e., beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), spironolactone, nitrates, statins, aspirin, and diuretics) was obtained from the patients’ medical records.

Type D personality

At inclusion, Type D personality was assessed by means of the Type D scale (DS14) [20]. This 14-item questionnaire consists of two subscales, Negative Affectivity (e.g., ‘I am often down in the dumps’) and Social Inhibition (e.g., ‘I am a closed kind of person’), each comprising 7 items. Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (‘false’) to 4 (‘true’). A standardized cut-off score ≥10 on both subscales is used to classify individuals with a Type D personality [20]. The cut-off score of ≥10 for both subscales has been confirmed as the most optimal by means of Item Response Theory (IRT) in samples from the general population, hypertensives, and CHD patients [21]. The co-occurrence of Negative Affectivity and Social Inhibition, and not solely the presence of negative emotions, predicted poor outcome following PCI [22]. Both subscales have good internal validity (Negative Affectivity: Cronbach’s α = .88 and Social Inhibition: Cronbach’s α = 0.86), are stable over a 3-month period (r = 0.82/0.72), and are independent of mood and health status [20]. The stability of Type D personality during an 18-month period has been demonstrated in a study in post-MI patients [23] and shown not to be confounded by disease severity [23].

Positive affect

Positive affect was assessed at inclusion by means of the Global Mood Scale (GMS) [24]. The positive affect subscale consists of 10 mood items (e.g., ‘active’ or ‘dynamic’) that are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘false’) to 4 (‘true’). Cronbach’s α for the subscale is .91, and the test–retest reliability over a three-month period is .57 [24]. The GMS positive affect score was dichotomised using a median split (i.e., ≥19) for categorizing low and high levels of positive affect, i.e., anhedonia versus no anhedonia, respectively.

Health status

The Dutch version of the Short-Form Health Survey12 (SF-12) was administered to assess generic health status [25, 26] at inclusion and at 12-month follow-up. This generic instrument measures overall physical and mental health status, as indicated by the Physical Component Scale Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores [27]. According to standard scoring procedures, all scale scores were standardized to the general US population (range [0–100], mean = 50, SD = 10), with higher scores indicating better functioning. The SF-12 has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid instrument [25].

Cardiac symptoms and feelings of disability

The 24-item Health Complaints Scale (HCS), a disease-specific questionnaire, was administered at inclusion to assess cardiac symptoms and feelings of disability [28]. Both the symptom (e.g., ‘tightness of the chest’ and ‘feeling weak’) and the feelings of disability (e.g., ‘feeling you are not able to do much’ and ‘worrying about your health’) subscale comprise 12 items that are scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘extremely’), with a score range from 0 to 48. A high score on both subscales indicate higher levels of complaints. The internal consistency of the HCS is good (.89<α<.91) and the test–retest reliability has proven to be adequate (r = .69) in cardiac patients [28, 29]. In the current sample, Cronbach’s α for the symptom subscale and feelings of disability subscale were .91 and .93, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics were examined using the chi-square test for dichotomous variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Three groups were composed, stratified by Type D personality and positive affect; i.e., a low-risk group of non-Type D without anhedonia, an intermediate risk group of non-Type D patients with anhedonia, and a high-risk group of Type D patients.

Linear regression analyses (Enter method), with non-Type D patients without anhedonia as the reference category, were conducted to examine anhedonia and Type D personality as predictors of impaired health status, cardiac symptoms, and feelings of disability at 12-month follow-up. In multivariable analyses, we adjusted for gender, age, partner status (having a partner vs. having no partner), lower educational level (primary schooling or lower vs. secondary schooling and higher), current smoking status, NYHA class (I–II vs. III–IV), LVEF, stroke or TIA, COPD, statins, calcium antagonists, diuretics, and health status at inclusion, cardiac complaints and feelings of disability at inclusion. Covariates were selected based on univariable analyses and the literature.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and P < .05 was used to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 14.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Responders versus non-responders

Respondents were more likely to be prescribed ACE-inhibitors (P = .07), digoxin (P = .03), and spironolactone (P = .04) than non-responders. Trends were also found for comorbid COPD (P = .08) and nitrates (P = .08), with respondents likely to have comorbid COPD and to be prescribed nitrates when compared with non-responders. No other differences emerged in demographic or clinical characteristics.

Patient characteristics

The prevalence of Type D personality was 20.2% in this sample. Patient characteristics stratified by Type D status and positive affect are presented in Table 1. Differences emerged between groups with respect to age, educational level, NYHA class, stroke/TIA, and prescription of calcium antagonists, with Type D patients being older when compared with non-Type D patients without anhedonia (P = .04). In addition, Type D patients had a lower educational level (P = .005), were more often classified in NYHA class III-IV (P = .003), prescribed calcium antagonists (P = .05), and diuretics (P = .04), but were less likely to have experienced a stroke or TIA (P = .04).

Positive affect, Type D personality, and health status

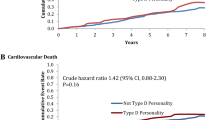

Mean physical and mental health status scores at 12 months for non-Type D patients with anhedonia, non-Type D patients with anhedonia and Type D patients are presented in Fig. 2a (top).

In comparison with the reference group of non-Type D patients without anhedonia, non-Type D patients with anhedonia and Type D patients reported lower levels of mental health status at 12-month follow-up (see Table 2; left, top). After controlling for demographic and clinical confounders, and mental health status at inclusion, both anhedonic non-Type D patients and Type D patients report lower levels of health status when compared with non-Type D patients without anhedonia (see Table 2; left, bottom). Further, being prescribed calcium-antagonists was an independent predictor of better mental health status at 12-month follow-up. A trend was shown for history of stoke or TIA to be independently associated with lower levels of mental health status at 12-month follow-up (see Table 2; left, bottom).

In univariable analyses, both non-Type D patients with anhedonia and Type D patients reported lower levels of physical health status at 12-months, compared with the reference group of non-Type D patients without anhedonia (see Table 2; right, top). In multivariable analyses, a trend was shown for non-Type D patients with anhedonia and Type D patients to report lower levels of physical health status at 12-month follow-up, when compared with the reference group (see Table 2; right, bottom). Further, female gender, being prescribed statins or calcium-antagonists were independent predictors of lower physical health status at follow-up. Better physical health status at inclusion was an independent predictor of better physical health status at follow-up. Finally, a trend was shown for having no partner to be associated with lower physical health status at 12-month follow-up (see Table 2; right, bottom).

Positive affect, Type D personality, cardiac symptoms and feelings of disability

Mean scores on cardiac symptoms and feelings of disability at 12 months for non-Type D patients with anhedonia, non-Type D patients with anhedonia and Type D patients are presented in Fig. 2b (bottom).

In univariable analyses, non-Type D patients with anhedonia and Type D patients reported more cardiac symptoms at 12-month follow-up, when compared with the reference group of non-Type D patients without anhedonia (Table 3; left, top). In multivariable analyses, Type D remained associated with higher levels of cardiac symptoms, but the association between non-Type D patients with anhedonia and higher levels of cardiac symptoms at 12-month follow-up was no longer significant. In addition, higher LVEF and cardiac symptoms at inclusion were independent predictors of more cardiac symptoms at 12-month follow-up (Table 3; left, bottom).

Non-Type D patients with anhedonia and Type D patients reported more feelings of disability at 12-months, when compared with the reference group of non-Type D patients without anhedonia, in univariable analyses (Table 3; right, top). After controlling for demographic and clinical variables, and scores at inclusion, both non-Type D patients with anhedonia and Type D patients still reported more feelings of disability at 12-month follow-up. Further, higher LVEF and feelings of disability at inclusion were independent predictors of higher levels of feelings of disability at 12-months. Finally, a trend was shown for higher age to be independently associated with more feelings of disability at 12-month follow-up (Table 3 right, bottom).

Discussion

In the present study, we identified group of CHF patients reporting lower levels of health status at 12 months, namely those patients classified as having no Type D personality, but low on positive affect. This specific group of anhedonic non-Type D patients were shown to report lower levels of mental and physical health status, as well as more feelings of disability at 12-month follow-up, when compared with non-Type D patients high on positive affect. Furthermore, Type D patients were shown to report lower levels of health status, more cardiac symptoms, and more feelings of disability, when compared with non-Type D patients high on positive affect.

In this study the findings on the detrimental effects of Type D personality on patient-centered outcomes in CHF were confirmed [30, 31]. Furthermore, we were able to identify a subgroup of anhedonic patients reporting lower levels of patient-centred outcomes. Post-hoc analyses demonstrated that these differences in patient-centred outcomes between groups were not only statistically relevant, but also clinically relevant, as effect sizes were overall large to very large (Cohen’s d). CHF outpatients with a Type D personality reported lower levels of physical and mental health status at 12-month follow-up. These findings are in line with those of Hu and colleagues showing that older community dwelling persons diagnosed with chronic disease (i.e., arthritis, CVD, COPD, or diabetes) high on positive affect and low on negative affect had better mental and physical health status [32]. Other studies that have also shown that lack of positive affect is associated with worse clinical outcome in patients with established CAD [9, 10]. However, in the current study we did not have information on hard medical outcomes, like readmission rates and major adverse clinical events.

Apart from psychological factors, demographic and clinical characteristics were associated with impaired health outcomes in the current study. Overall, demographic and clinical factors were more likely to be related to physical health status than to mental health status at 12-months. For instance, we found female gender and having no partner to be associated with lower levels of physical health status, which has also been demonstrated by others [33]. Nevertheless, the impact of marital status has not received considerable attention, but there are indications that single marital status and poor marital quality are associated with mortality in CHF.

Limitations of the current study must be acknowledged. First, the present study relied on self-reported outcomes. Nevertheless, all instruments administered are standardized measures that have been shown to be valid and reliable. In addition, the evaluation of patient-centred outcomes is of importance as there is a known discrepancy in physician and patient ratings of functioning, with physicians tending to underestimate the disabilities of patients [34]. Further, the evaluation of health status is advocated by guidelines for treatment [35, 36], since impaired health status is predictive of mortality in CHF [37, 38] and generally patients report to prefer better health status over prolonged survival [39]. Second, in the present study only patients visiting the outpatient clinic were approached for participation. Consequently, the results cannot be generalized to clinical heart failure samples. In this study, levels of positive affect were dichotomized. Future studies need to further explore whether a dose-response relationship exists between levels of positive affect and patient-centred outcomes. Further, from this study no conclusions regarding causality can be drawn, because of the study design. Finally, residual confounding might have affected the results from the present study, although we adjusted for various confounders in multivariable analyses. A strength of the current study comprises the use of both generic as well as cardiac disease-specific instruments for the evaluation of health outcomes. Future studies could include psychometrically sound CHF-specific health status questionnaires, to specifically evaluate health status in this particular patient group [40].

From a clinical point of view, the present study underlines the importance of evaluating psychological risk factors, and in particular the clustering of psychological risk factors, as this enables the identification of different risk groups. This has also been advocated by others [41]. Given that impaired health status has been associated with poor prognosis in CHF [37], non-Type D patients low on positive affect and patients with a Type D personality should be identified in clinical practice, as they might need additional support and adjunctive intervention in order to experience health status levels comparable with other patients. Interventions might consist of improving skills to experience more positive affect by means of cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction. These types of psychological treatment have shown to be beneficial for improving positive affect in medically ill patients [42, 43] and in older depressed patients at increased cardiovascular risk [44].

In conclusion, we identified a specific group of CHF outpatients at risk for reporting impaired health outcomes, in the present study, namely those patients low on positive affect, and not classified as having a Type D personality. In addition, Type D patients also reported lower levels of health status, when compared with the reference group. Future studies are warranted to replicate the current and to determine the associations between positive affect and hard outcomes in CHF.

Abbreviations

- ARB:

-

Angiotensin receptor blockers

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CHF:

-

Chronic heart failure

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DS14:

-

Type D scale

- GMS:

-

Global mood scale

- HCS:

-

Health complaints scale

- IRT:

-

Item response theory

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- MCS:

-

Mental component summary

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association functional class

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PAD:

-

Peripheral arterial disease

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- PCS:

-

Physical component summary

- SF-12:

-

Short form-12

- TIA:

-

Transient ischemic attack

References

Rozanski, A., Blumenthal, J. A., Davidson, K. W., Saab, P. G., & Kubzansky, L. (2005). The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of psychosocial risk factors in cardiac practice: The emerging field of behavioral cardiology. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 45, 637–651. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.005.

Chida, Y., & Steptoe, A. (2008). Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70, 741–756. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Larsen, J. T., McGraw, A. P., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2001). Can people feel happy and sad at the same time? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 684–696. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.684.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465–490. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.465.

Smart Richman, L., Kubzanksy, L., Maselko, J., Kawachi, I., Choo, P., & Bauer, M. (2005). Positive emotion and health: Going beyond the negative. Health Psychology, 24, 422–429. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.422.

Kubzansky, L. D., & Thurston, R. C. (2007). Emotional vitality and incident coronary heart disease: Benefits of healthy psychological functioning. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 1393–1401. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1393.

Nabi, H., Kivimaki, M., De Vogli, R., Marmot, M. G., & Singh-Manoux, A. (2008). Positive and negative affect and risk of coronary heart disease: Whitehall II prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 337, a118. doi:10.1136/bmj.a118.

Middleton, R., & Byrd, K. (1996). Psychosocial factors and hospital readmission status of older persons with cardiovascular disease. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 27, 3–10.

Denollet, J., Pedersen, S. S., Daemen, J., de Jaegere, P., Serruys, P. W., & van Domburg, R. T. (2008). Reduced positive affect (anhedonia) predicts major clinical events following implantation of coronary-artery stents. Journal of Internal Medicine, 263, 203–211.

Rumsfeld, J. S., MaWhinney, S., McCarthy, M., et al. (1999). Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Participants of the department of veterans affairs cooperative study group on processes, structures, and outcomes of care in cardiac surgery. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281, 1298–1303. doi:10.1001/jama.281.14.1298.

Kubzansky, L. D., Sparrow, D., Vokonas, P., & Kawachi, I. (2001). Is the glass half empty or half full? A prospective study of optimism and coronary heart disease in the Normative Aging Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63, 910–916.

Brummett, B. H., Boyle, S. H., Siegler, I. C., Williams, R. B., Mark, D. B., & Barefoot, J. C. (2005). Ratings of positive and depressive emotion as predictors of mortality in coronary patients. International Journal of Cardiology, 100, 213–216. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.06.016.

Prather, A. A., Marsland, A. L., Muldoon, M. F., & Manuck, S. B. (2007). Positive affective style covaries with stimulated IL-6 and lL-10 production in a middle-aged community sample. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 21, 1033–1037. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.009.

Steptoe, A., Gibson, E. L., Hamer, M., & Wardle, J. (2007). Neuroendocrine and cardiovascular correlates of positive affect measured by ecological momentary assessment and by questionnaire. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 32, 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.10.001.

Al-Ruzzeh, S., Athanasiou, T., Mangoush, O., et al. (2005). Predictors of poor mid-term health related quality of life after primary isolated coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Heart (British Cardiac Society), 91, 1557–1562. doi:10.1136/hrt.2004.047068.

Denollet, J., Pedersen, S. S., Vrints, C. J., & Conraads, V. M. (2006). Usefulness of Type D personality in predicting five-year cardiac events above and beyond concurrent symptoms of stress in patients with coronary heart disease. The American Journal of Cardiology, 97, 970–973. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.035.

Schiffer, A. A., Pedersen, S. S., Broers, H., Widdershoven, J. W., & Denollet, J. (2008). Type D personality but not depression predicts severity of anxiety in heart failure patients at 1-year follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders, 106, 73–81. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.021.

Graham, I., Atar, D., Borch-Johnsen, K., et al. (2007). European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Full text. Fourth joint task force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, 14(Suppl. 2), S1–S113. doi:10.1097/01.hjr.0000277983.23934.c9.

Denollet, J. (2005). Ds14: Standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and Type D personality. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 89–97. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000149256.81953.49.

Emons, W. H., Meijer, R. R., & Denollet, J. (2007). Negative affectivity and social inhibition in cardiovascular disease: Evaluating Type D personality and its assessment using item response theory. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63, 27–39. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.03.010.

Denollet, J., Pedersen, S. S., Ong, A. T., Erdman, R. A., Serruys, P. W., & van Domburg, R. T. (2006). Social inhibition modulates the effect of negative emotions on cardiac prognosis following percutaneous coronary intervention in the drug-eluting stent era. European Heart Journal, 27, 171–177. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi616.

Martens, E., Kupper, N., Pedersen, S., Aquarius, A., & Denollet, J. (2007). Type D personality is a stable taxonomy in post-mi patients over an 18-month period. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 65, 545–550. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.06.005.

Denollet, J. (1993). Emotional distress and fatigue in coronary heart disease: The Global Mood Scale (GMS). Psychological Medicine, 23, 111–121.

Ware, J., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1996). A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34, 220–233. doi:10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003.

Gandek, B., Ware, J. E., Aaronson, N. K., et al. (1998). Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 health survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA project. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51, 1171–1178. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00109-7.

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., Bayliss, M. S., McHorney, C. A., Rogers, W. H., & Raczek, A. (1995). Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: Summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Medical Care, 33, 264–279. doi:10.1097/00005650-199501001-00005.

Denollet, J. (1994). Health complaints and outcome assessment in coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 56, 463–474.

Pedersen, S. S., & Denollet, J. (2002). Perceived health following myocardial infarction: Cross-validation of the Health Complaints Scale in Danish patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 1221–1230. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00027-X.

Schiffer, A. A., Pedersen, S. S., Widdershoven, J. W., Hendriks, E. H., Winter, J. B., & Denollet, J. (2005). The distressed (Type D) personality is independently associated with impaired health status and increased depressive symptoms in chronic heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, 12, 341–346. doi:10.1097/01.hjr.0000173107.76109.6c.

Schiffer, A. A., Pedersen, S. S., Widdershoven, J. W., & Denollet, J. (2008). Type D personality and depressive symptoms are independent predictors of impaired health status in chronic heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure, 10, 802–810. doi:10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.06.012.

Hu, J., & Gruber, K. J. (2008). Positive and negative affect and health functioning indicators among older adults with chronic illnesses. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 29, 895–911. doi:10.1080/01612840802182938.

Luttik, M. L., Jaarsma, T., Veeger, N., & van Veldhuisen, D. J. (2006). Marital status, quality of life, and clinical outcome in patients with heart failure. Heart and Lung, 35, 3–8. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.08.001.

Goode, K. M., Nabb, S., Cleland, J. G., & Clark, A. L. (2008). A comparison of patient and physician-rated New York Heart Association class in a community-based heart failure clinic. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 14, 379–387. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.01.014.

Krumholz, H. M., Peterson, E. D., Ayanian, J. Z., et al. (2005). Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on outcomes research in cardiovascular disease. Circulation, 111, 3158–3166. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.536102.

Swedberg, K., Cleland, J., Dargie, H., et al. (2005). Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: Executive summary (update 2005). European Heart Journal, 26, 1115–1140. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi204.

Soto, G. E., Jones, P., Weintraub, W. S., Krumholz, H. M., & Spertus, J. A. (2004). Prognostic value of health status in patients with heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation, 110, 546–551. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000136991.85540.A9.

Heidenreich, P. A., Spertus, J. A., Jones, P. G., et al. (2006). Health status identifies heart failure outpatients at risk for hospitalization or death. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 47, 752–756. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.021.

Stanek, E. J., Oates, M. B., McGhan, W. F., Denofrio, D., & Loh, E. (2000). Preferences for treatment outcomes in patients with heart failure: Symptoms versus survival. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 6, 225–232. doi:10.1054/jcaf.2000.9503.

Garin, O., Ferrer, M., Pont, A., et al. (2009). Disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires for heart failure: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Quality of Life Research, 18, 71–85. doi:10.1007/s11136-008-9416-4.

Rozanski, A., Blumenthal, J. A., & Kaplan, J. (1999). Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation, 99, 2192–2217.

Grossman, P., Tiefenthaler-Gilmer, U., Raysz, A., & Kesper, U. (2007). Mindfulness training as an intervention for fibromyalgia: Evidence of postintervention and 3-year follow-up benefits in well-being. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 76, 226–233. doi:10.1159/000101501.

Mohr, D. C., Hart, S. L., Julian, L., et al. (2005). Telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 1007–1014. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.1007.

Strachowski, D., Khaylis, A., Conrad, A., Neri, E., Spiegel, D., & Taylor, C. B. (2008). The effects of ognitive behavior therapy on depression in older patients with cardiovascular risk. Depression and Anxiety, 25, e1–e10. doi:10.1002/da.20302.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Angélique A. Schiffer, PhD, for providing us with the data that were collected at the TweeSteden Ziekenhuis, Tilburg, The Netherlands. The present study was supported by a VICI-grant (453-04-004) from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, The Hague, The Netherlands, to Johan Denollet, PhD.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pelle, A.J., Pedersen, S.S., Szabó, B.M. et al. Beyond Type D personality: reduced positive affect (anhedonia) predicts impaired health status in chronic heart failure. Qual Life Res 18, 689–698 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9485-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9485-z