Abstract

We consider the quadratic voting mechanism (Lalley and Weyl in Quadratic voting. Working paper, University of Chicago, 2015; Weyl in The robustness of quadratic voting. Working paper, University of Chicago, 2015) and focus on the incentives it provides individuals deciding what proposals or candidates to put up for a vote. The incentive compatibility of quadratic voting rests upon the assumption that individuals value the money used to buy votes, while the budget balance/efficiency of the mechanism requires that the money spent by one voter by redistributed among the other voters. From these assumptions, we show that it follows that strategic proposers will have an incentive to offer proposals with greater uncertainty about individual values. Similarly, we show that, in an electoral setting, quadratic voting provides an incentive to propose candidates with polarized, non-convergent platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Schattschneider (1960, p. 68), emphasis in the original.

Also, we consider it reasonable from a behavioral standpoint that individual choices within a setting QV would be well approximated by a linear voting rule consistent with Eq. (1).

The case of \(u_{i}<0\) is symmetric.

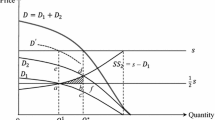

The situation is symmetric if one allows for \(\mu \in [-{\,^1\!/_2},0)\), and \(|\mu |>{\,^1\!/_2}\) implies that neither voter 1 nor voter 2 will bid in equilibrium, meaning that voter 3 would receive zero rebate in such situations.

Note that \(u_{i}\approx -(\mu +{\,^1\!/_2})\) occurs with probability zero for \(\mu \ne 0\).

This presumes that, when \(\sum v_{i}=0\), the project is approved. Otherwise, a pure strategy equilibrium will not exist in the QV for \(\mu \ge {\,^1\!/_2}\).

For example, suppose that, after majority rule or QV is selected as the collective choice mechanism, voter 3 chooses to whether to pay a cost \(c>0\) in order to choose \(\mu\) and, if not, then (say) \(\mu\) is set to some exogenous value, \({\hat{\mu }}>0\). If c is small enough relative to \({\hat{\mu }}\) and QV is chosen as the collective choice mechanism, then voter 3 would pay the cost c and set \(\mu =0\).

This finding is in line with the experimental findings of Goeree and Zhang (2016). In an 11-person private values setting, Goeree and Zhang find that “moderate” voters—those whose values were closer to 0—benefitted from the redistributive aspect of quadratic voting.

Formally, voter 2 will receive half of each of their payments. This matters only when we allow for more than 3 voters. The case of three voters maximizes the strength of voter 2’s incentive to manipulate x in pursuit of a larger rebate from the ensuing QV election.

What is potentially very important—but remains very important when the group must choose between three or more mutually exclusive options—is the nature of individuals’ information about their own preferences. We do not touch upon this issue in any depth in this article, but allowing for correlation between voters’ true preferences in the presence of asymmetric and incomplete information (at the voter level) about these preferences would seem to present a difficult challenge for someone interested in achieving (perhaps even approximate) ex post efficiency.

References

Black, D. (1948). On the rationale of group decision-making. Journal of Political Economy, 56(1), 23–34.

Cox, G. W., & McCubbins, M. D. (2005). Setting the agenda: Responsible party government in the U.S. House of Representatives. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Epstein, G. S., & Nitzan, S. (2006). The politics of randomness. Social Choice and Welfare, 27(2), 423–433.

Fang, H. (2002). Lottery versus all-pay auction models of lobbying. Public Choice, 112(3–4), 351–371.

Goeree JK, Zhang J (2016) One man, one bid. Games and Economic Behavior. doi:10.1016/j.geb.2016.10.003.

Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown.

Lalley, S. P., & Weyl, E. G. (2015). Quadratic voting. Working paper, University of Chicago

Myerson, R. B., & Satterthwaite, M. A. (1983). Efficient mechanisms for bilateral trading. Journal of Economic Theory, 29(2), 265–281.

Nti, K. O. (1999). Rent-seeking with asymmetric valuations. Public Choice, 98(3–4), 415–430.

Perry, H.W. (2009). Deciding to decide: Agenda setting in the United States Supreme Court. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rasch, B. E. (2000). Parliamentary floor voting procedures and agenda setting in Europe. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 25(1), 3–23.

Riker, W. H. (Ed.). (1993). Agenda formation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Schattschneider, E. (1960). The semisovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. Holt, Rinehart and Winston: Austin.

Siegel, R. (2009). All-pay contests. Econometrica, 77(1), 71–92.

Weyl, E. G. (2015). The robustness of quadratic voting. Working paper, University of Chicago.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Sean Ingham and Glen Weyl for their helpful comments.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patty, J.W., Penn, E.M. Uncertainty, polarization, and proposal incentives under quadratic voting. Public Choice 172, 109–124 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-017-0406-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-017-0406-3