Abstract

Focusing on executive orders (EOs) and extending previous models, we present a general theoretical framework of unilateral presidential action. This framework allows us to examine systematically how various possible party roles, such as agenda setting, result in legislative gridlock which, in turn, create or undercut presidential incentives, and how directional constraints on discretion undermine presidential leverage. In particular, negative agenda setting and party discipline intensify gridlock, enhancing presidential policy gains; positive agenda setting’s effect depends upon governmental regime. Empirically, majority parties consistently play some role, especially negative agenda setting, regardless of the threshold used to define EO significance, while party discipline is more pronounced with higher thresholds. Also, while a majority party median is crucial for constraining the direction of how presidents use discretion with lower thresholds, a chamber median (whose preference may be induced by party pressure) is key with higher thresholds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Admittedly, modeling other transaction costs that Congress incurs goes beyond the scope of this paper. Likewise, we do not consider corresponding costs that presidents bear in issuing EOs, including coordinating agency efforts (e.g., Rudalevige 2012), which might deter them analogously to how other transaction costs might stymie legislators.

As we discuss in greater depth shortly, alternatively assuming that discretion is a function of the status quo changes our results little.

Our model is also more realistic than past efforts by assuming a bicameral rather than a unicameral legislature.

Our analysis is structural: Predictions are based on models assuming alternative sets of party roles and directional constraints on presidential discretion, which are then compared with respect to how they fit the data. Not only is this approach similar in spirit to work such as Chiou and Rothenberg’s (2003) analysis of lawmaking and Primo et al.’s (2008) study of federal judicial appointments—where formal theories are explicated—but also to exclusively empirical research—where assumptions are nonetheless made, if less explicitly—comparing different statistical models or even testing a single model (e.g., Shipan 2004).

Given this approach, originally proposed by Volden and Bergman (2006), the ideal points of members from each party move toward their party medians in a uni-dimensional policy space. As a result, tighter discipline in the two major parties will polarize the legislature. At the extreme, party members converge to their party medians with perfect party discipline.

In trying to balance comprehensiveness and parsimony, we omit one potential party role—the president serving as his party’s leader to control the legislative agenda or to discipline his party’s members (e.g., Patterson and Calderia 1988; Sundquist 1989; Rohde 1991; Miller 1993). We make this choice because, as Chiou and Rothenberg (2003) show theoretically and empirically, substituting the assumption that the president rather than party medians are the party leaders changes results very little. Adding another set of models with the president as party leader would dramatically increase the number of models analyzed, further complicating presentation of our theoretical and empirical results.

In a model with unicameralism, positive agenda setting naturally incorporates negative agenda setting, as a legislator with positive agenda setting power will not propose legislation undermining his or her interests and, therefore, will also exercise negative agenda power. However, there are two chamber/party medians in our bicameral setup. While one chamber/party median possessing positive agenda power also can exercise negative agenda power, the other chamber/party median’s role is uncertain. To be concise, in our positive agenda setting model we assume that the latter has negative agenda power; however, our theoretical and empirical results for when the president will take unilateral action are almost identical without this assumption.

Since each chamber has its median, we assume that one median is the agenda setter and the other is a legislative pivot. Because which median is more justifiably the agenda setter is unclear, we essentially assume that each is equally likely and average out our results at the end. The analogous assumption is made for the model wherein the majority party is given positive agenda power.

Without loss of generality, we assume a Republican president. Since the president is empirically at least as extreme as the override pivots or majority medians, we make this assumption so that the override pivots, instead of the president, are relevant in determining the gridlock interval. By the same token, we assume that the president is more conservative than the majority party medians and the filibuster pivot. Relaxing these assumptions alters our results very little.

A possible alternative assumption is that the court is a strategic player, with its own policy preferences, which induces unilateral presidential action to move policy in a direction consistent with the judges’ policy interests. Howell (2003) discusses this assumption but does not employ it for generating hypotheses for his empirical analysis of significant executive orders, likely because considerable empirical difficulties are associated with utilizing this assumption. It is for such empirical difficulties that we exclude the possibility here.

Note that, for consistency’s sake, when parties are assumed to be capable of influencing their members in the legislative stage and chamber medians are assumed to constrain the presidential use of discretion, induced chamber medians, rather than chamber medians net of party pressure, are assumed to be the de facto discretion constraint.

For example, we could adapt it to encompass myriad models wherein the court is a strategic actor with preferences that differ from other players. Or we could focus on particular policies by including relevant committee medians as pivots.

While our models assume bicameralism, we assume unicameralism in our figures to make them more easily understood.

To foreshadow our empirical analysis, we will incorporate an additional step beyond measuring the UAI to compare the competing models.

This is why we get very similar results even if we assume that discretion is a function of the status quo or that the status quos are not concentrated within the EGI.

For comparison and illustration, we fix the preferences of relevant players and assume that the presidential party’s median coincides with the override pivot. Online Appendix B provides more details about equilibrium policy outcomes associated with each case depicted in Fig. 3.

To be concise in our presentation we do not demonstrate the effects of imperfect party discipline. Such discipline generally will simultaneously expand both EGI boundaries, augmenting the gridlock and preemption motives. The effect of imperfect discipline is largely similar to that of negative agenda power under various discretion assumptions.

As indicated, focusing on EOs follows the great bulk of the literature. We recognize that, in recent years, other means of acting unilaterally have been used more than in the past. For example, President Obama (whose actions are not covered in our analysis) has issued a large number of executive memoranda (e.g., Lowande 2014 finds that of the 693 memoranda issued between 1946 and 2013, about one-quarter were issued during Obama’s first 5 years).

For example, parties may play different roles for highly significant actions relative to more moderately significant moves, so models assuming certain party roles might gain more empirical support when EOs must satisfy a very high significance threshold to be categorized as worthy of counting.

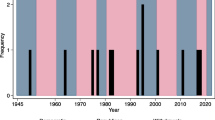

Since each EO’s significance score is estimated, our dependent variable is partially generated from estimated results and, therefore, may contain some errors for which we do not account. However, since the vast majority of our results are continuous with increasing thresholds (i.e., there are not identifiable break points) and remarkably robust, and given that controlling for these errors is quite cumbersome, it would seem that the payoffs from building in this additional error structure is not commensurate with the considerable effort involved.

While knowing the discretion level is not crucial in assessing our competing models, to be consistent with our theoretical assumptions we assume that discretion is drawn from a uniform distribution, with various upper bounds examined for sensitivity analysis. As we will see, not surprisingly the assumption about discretion’s upper bound does not change our empirical results.

We calculate the induced preferences of relevant players by taking a linear combination of their party leaders’ and their own primitive preferences, with the weight being the level of party pressure, which is estimated in Snyder and Groseclose (2000). As the Snyder-Groseclose estimates are available only up to the 105th Congress, we employ the same estimate for the next Congresses, partly because party pressure seems rather stable between the 104th and 107th Congresses and partly because the numerical values of the dependent variable have to be identical across the models which we seek to compare.

Since this independent variable is generated partly from common space scores and partly from our theoretical models, we admittedly omit controlling for the standard errors arising from estimating these scores, as does all previous work employing common space scores. Resolving this problem would require information not only about the standard error of each pivot’s common space score but also about the correlation between relevant pivots determining the UAI, the latter of which is unavailable. In principle, we could alternatively control for these errors by using a Bayesian procedure to estimate jointly common space scores of all legislators voting from 1947 through 2002, producing standard errors for each legislator and the UAI, and estimating the posterior mean of the coefficient of the expected incentive. In reality, this is computationally impossible at present given the sheer numbers of legislators and votes involved.

This independent variable is incorporated in previous studies with different rationales. Its inclusion here is guided by our empirical goal of identifying which of the competing model(s) receives more empirical support. We should emphasize that we only measure features that directly come from our theoretical framework—the expected incentives for unilateral action and the first White House term. Beyond now common warnings that merely throwing additional control variables into estimation is not desirable (e.g., Achen 2005), our small sample size makes including other independent variables problematic. Nonetheless, for a robustness check, we include presidential approval and the so-called misery index, two commonly included controlled variables, as well as a dummy variable for whether there is party switch in Congress (to capture similar effects to a president’s first term), and find that our basic inferences hold.

We take advantage of our theoretical results to guide our empirical investigation by requiring that the sign of the coefficient be consistent with our theoretical expectation. Even if we adopt a barefoot empiricist perspective, and do not consider such expectations in ascertaining which model(s) best fit the data, our empirical conclusions largely hold.

The BIC is measured as (–2*log likelihood) + (number of parameters)*ln(number of observations) (see equation (23) in Raftery 1995). The alternative to the BIC is the Akaike Information Criterion. For our results, which of the two we adopt is immaterial because they differ only in how they account for the number of independent variables there are in assessing model fit, and all of our estimates are based on the same number of independent variables. We employ the BIC just to be consistent with Raftery’s term and the test that he employed.

First presidential term is virtually always correctly signed and significant.

For a standard deviation increase from the mean of expected incentives, holding the other independent variable at its mean, the president’s expected mean EO issuance increases 19 %.

This directional discretion constraint assumption is not quite compatible with the only-preference assumption in the legislative stage but, for the sake of consistency, we include it in our empirical analysis.

Notice that the model where majority party medians act as a discretion constraint and exercise positive agenda setting with or without discipline does as well as the best model when the threshold is between 1 and 1.5. This is the only occasion wherein positive agenda setting becomes prominent among party roles.

In this model, increasing expected incentives from its mean to a standard deviation above it, holding the other independent variable at its mean, leads to a 34 % increase in the expected number of EOs issued.

Also, as implied, although they are not derived from our theoretical analysis, we include a number of alternative variables to test the robustness of our analysis: presidential approval (average value by Congress using Gallup data), the so-called misery index (see http://www.miseryindex.us/indexbyCongress.aspx), and various alternative measures of when party switches in Congress. In all instances (results available from authors), our main results regarding our primary independent variables (i.e., expected incentives and first presidential term) and comparisons of our competing models remain very similar.

We emphasize that our results are only consistent and not definitive proof; indeed, the relationship between Congress and the courts is generally recognized as amorphous and not particularly well-understood (e.g., Bailey et al. 2012).

Precisely speaking, we are referring to EOs whose significance thresholds exceed 1.5.

The congressional agenda setter will not introduce a bill to override unilateral presidential action in step (4) if and only if z = y (i.e., if the status quo at the beginning of legislative stage is within the EGI).

Consistent with the literature, throughout our theoretical framework we assume that the president will neither take unilateral action that will be overridden by Congress or the court nor move the status quo further away from the EGI (the latter assumption ruling out some inconceivable presidential actions that will damage the chief executive’s reputation).

See online Appendix A for the proof.

Here we assume a unified Congress. Under a divided Congress, x = q for those status quos between the majority party medians in the House and Senate. Our empirical results also account for the divided Congress case. We should also note is that if we assume that the court is a strategic actor and acts as a directional constraint on presidential discretion our theoretical results would be the same as those under the rule of C2, except that the ideal point of the chamber median would be replaced by that of the court.

References

Achen, C. H. (2005). Let’s put garbage-can regressions and garbage-can probits where they belong. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 22, 327–339.

Bailey, M. A., Maltzman, F., & Shipan, C. R. (2012). The amorphous relationship between Congress and the courts. In G. C. Edwards, F. E. Lee, & E. Schickler (Eds.), The handbook of political economy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Berry, C. R., Burden, B. C., & Howell, W. G. (2010). The president and the distribution of federal spending. American Political Science Review, 104, 783–799.

Bond, J. R., & Fleisher, R. (1990). The president in the legislative arena. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boyle, S. C. (2007). Consultation, cooperation, and delegation: Presidential power in the twenty-first century. PhD dissertation, University of Florida, Department of Political Science.

Cameron, C. M. (2006). The political economy of the US presidency. In B. Weingast & D. Wittman (Eds.), The handbook of political economy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chiou, F.-Y., & Rothenberg, L. S. (2003). When pivotal politics meets partisan politics. American Journal of Political Science, 47, 503–522.

Chiou, F.-Y., & Rothenberg, L. S. (2009). A unified theory of U.S. lawmaking: Preferences, institutions, and party discipline. Journal of Politics, 71, 1257–1272.

Chiou, F.-Y., & Rothenberg, L. S. (2014). Elusive search for presidential power. American Journal of Political Science, 58, 653–663.

Clarke, K. A. (2001). Testing nonnested models of international relations: Reevaluating realism. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 724–744.

Cooper, P. J. (1986). By order of the president: Administration by executive order and proclamation. Administration & Society, 18, 233–262.

Cox, G. W., & McCubbins, M. D. (2005). Setting the agenda: Responsible party government in the U.S. House of Representatives. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cox, G. W., & McCubbins, M. D. (2007). Legislative leviathan: Party government in the House (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cox, G. W., & Poole, K. T. (2002). On measuring partisanship in roll-call voting: The U.S. House of Representatives, 1877-1999. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 477–489.

Crain, W. M., & Tollison, R. D. (1979). The executive branch in the interest-group theory of government. Journal of Legal Studies, 8, 555–567.

Deering, C. J., & Maltzman, F. (1999). The politics of executive orders: Legislative constraints on presidential power. Political Research Quarterly, 52, 767–783.

Dickinson, M. J. (2009). We all want a revolution: Neustadt, new institutionalism, and the future of presidency research. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 39, 736–770.

Epstein, D., & O’Halloran, S. (1999). Delegating powers: A transaction cost politics approach to policy making under separate powers. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Howell, W. G. (2003). Power without persuasion: The politics of direct political action. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Howell, W. D. (2005). Unilateral powers: A brief overview. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 35, 417–439.

Krause, G., & Cohen, D. (2000). Opportunity, constraints, and the development of the institutional presidency: The issuance of executive orders issuance, 1939-1996. Journal of Politics, 62, 88–114.

Krehbiel, K. (1993). Where’s the party? British Journal of Political Science, 23, 235–266.

Krehbiel, K. (1998). Pivotal politics: A theory of U.S. lawmaking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kriner, D. L., & Reeves, A. (2012). The influence of federal spending on presidential elections. American Political Science Review, 106, 348–366.

Lewis, D. E. (2008). The politics of presidential appointments: Political control and bureaucratic performance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lowande, K. S. (2014). The contemporary presidency after the orders: Presidential memoranda and unitary action. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 44, 724–741.

Mayer, K. R. (2002). With the stroke of a pen: Executive orders and presidential power. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mayer, K. R. (2009). Going alone: The presidential power of unilateral action. In G. C. Edwards III & W. G. Howell (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the American presidency. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mayer, K. R., & Price, K. (2002). Unilateral presidential powers: Significant executive orders, 1949-1999. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 32, 367–386.

Miller, G. (1993). Formal theory and the presidency. In G. C. Edwards III, J. H. Kessel, & B. A. Rockman (Eds.), Researching the presidency: Vital questions, new approaches. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Moe, T. M., & Howell, W. G. (1999). The presidential power of unilateral action. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 15, 132–179.

Monroe, N. W., Roberts, J. M., & Rohde, D. W. (2008). Electoral accountability, party loyalty, and roll-call voting in the U.S. Senate. In N. W. Monroe, J. M. Roberts, & D. W. Rohde (Eds.), Why not parties? Party effects in the United States Senate. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Neustadt, R. E. (1990). Presidential power and the modern presidents: The political of leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan. New York: Free Press.

Patterson, S. C., & Calderia, G. A. (1988). Party voting in the United States Congress. British Journal of Political Science, 18, 111–131.

Poole, K. T. (1998). Recovering a basic space from a set of issue scales. American Journal of Political Science, 42, 954–993.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (1997). Congress: A political-economic history of roll call voting. New York: Oxford University Press.

Primo, D. M., Binder, S. A., & Maltzman, F. (2008). Who consents? Competing pivots in federal judicial selection. American Journal of Political Science, 52, 471–489.

Raftery, A. E. (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology, 25, 111–163.

Rohde, D. W. (1991). Parties and leaders in the postreform house. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rudalevige, A. (2012). Executive orders and presidential unilateralism. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 42, 138–160.

Shipan, C. R. (2004). Regulatory regimes, agency actions, and the conditional nature of political influence. American Political Science Review, 98, 467–480.

Shughart, W. F, I. I., & Tollison, R. D. (1998). Interest groups and the courts. George Mason Law Review, 6, 953–969.

Smith, S. S. (2007). Partisan influence in Congress. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, S. S, Roberts, J. M., & Vander Wielen, R. J. (2009). The American Congress (6th ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Snyder, J. M, Jr., & Groseclose, T. (2000). Estimating party influence in congressional roll-call voting. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 193–211.

Sundquist, J. (1989). Needed: A political theory for the new era of coalition government in the United States. Political Science Quarterly, 103, 613–635.

Volden, C., & Bergman, E. (2006). How strong should our party be? Party member preferences over party cohesion. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 31, 71–104.

Warber, A. L. (2006). Executive orders and the modern presidency: Legislating from the Oval Office. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner.

Waterman, R. W. (2009). Assessing the unilateral presidency. In G. C. Edwards III & W. G. Howell (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the American presidency. New York: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: Formal presentation of model, proposition 1, and expected incentives of unilateral action

Appendix: Formal presentation of model, proposition 1, and expected incentives of unilateral action

Assume that every player, except the court, has a symmetric single-peaked preference with an ideal point whose notation coincides with that of the player. So, in step (5) of the game sequence, each legislative pivot will not veto if and only if the new status quo established by the agenda setter in Congress makes him or her better off than the status quo generated from the unilateral presidential action (i.e., if the former is closer to his or her ideal point than the latter). Given these decisions made by legislative pivots, we can obtain the set of status quos unaltered in the legislative stage comprising the equilibrium gridlock interval EGI (Krehbiel 1998). By Chiou and Rothenberg (2009), G L = min{A, L} and G R = max{A, L}, where G L and G R are denoted as the EGI’s left and right bounds, respectively, and where A and L denote the agenda setter and the set of legislative pivots in a given game. Furthermore, denote y as the status quo in the beginning of the legislative stage (i.e., at the start of step (3)). The agenda setter A’s proposal z is a function of y, as given belowFootnote 38:

We formally express alternative assumptions about directional constraints on presidential discretion’s use as follows. Let M = min{M H , M S } be the chamber median further away from the president. Let MP = min{MP H , MP S } under divided government and MP = max{MP H , MP S } under unified government. For the president’s unilateral action x, we can state the following three rules, each of which corresponds to the mechanisms mentioned above sequentially:

- C1:

-

unilateral presidential action will be sustained if and only if \(x - q/ \le t\)

- C2:

-

unilateral presidential action will be sustained if and only if \(\left| {x - q} \right| \le t\) and \((x - q)(M - q) \ge 0\) for \(q \ne M\)

- C3:

-

unilateral presidential action will be sustained if and only if \(\left| {x - q} \right| \le t\) and \((x - q)(MP - q) \ge 0\) for \(q \ne MP.\)

In words, rule C1 means that the president’s unilateral action cannot move the status quo more than t. Rule C2 (C3) implies that, in addition to the constraint in C1, the president’s action is permissible only for those moves in the direction of the chamber medians (majority party medians) in both legislative chambers.

Given the result above, we can now state the equilibrium unilateral action, denoted by \(x*\), with unilateral action occurring when \(x* \ne q\).Footnote 39

Proposition 1

Given that Nature draws t and q, Footnote 40

-

(1)

Under rule C1, when \(A < G_{R}\),

When \(A = G_{R}\)

-

(2)

Under rule C2 (C3), \(x^{*}\) is the same as under rule C1, except that \(x^{*} = q\) for \(q \in (M,G_{R} )\) (q locating between MP and G R ).Footnote 41

We calculate the expected incentives for unilateral action by integrating possible unilateral action over some distributions of discretion and status quos, i.e., \(\Pr (x^{*} \ne q) = \iint {\Pr (x^{*} \ne q|t,q)}g(t)g(q)dtdq\), where \(g(t)\) and \(g(q)\) are the distributions of discretion and the status quos, respectively, and \(\Pr (x^{*} \ne q|t,q)\) represents the probability of unilateral action given \(t\) and \(q\) being drawn. To reiterate, and as seen in Proposition 1, \(\Pr (x^{*} \ne q|t,q) = 1\) for some \(q\) regardless of the values of \(t\), but \(\Pr (x^{*} \ne q|t,q) = 0\) for some others. Therefore, \(\Pr (act) = \Pr (x^{*} \ne q)\) formally defines the unconditional expected incentive for unilateral action. As mentioned, this implies that a higher \(\Pr (act)\) is associated with more significant EOs being issued during a given Congress, a hypothesis which we can examine empirically for each of our 18 models.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chiou, FY., Rothenberg, L.S. Presidential unilateral action: partisan influence and presidential power. Public Choice 167, 145–171 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0335-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0335-6