“Major parties, let it be said for the hundredth time, are complex structures held together by the fact that disunity means defeat, the fact that the opposition is strong enough to take advantage of any failure of the party in power to maintain a united front”. Schattschneider (1942 , p. 95)

Abstract

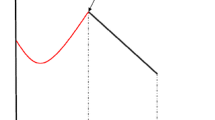

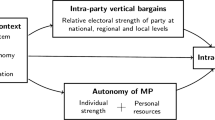

Under what conditions do political parties split? This paper presents a model of intra-party politics to explain party unity in parliamentary systems. The theory derived from an incomplete information game predicts that parties split with positive probability, which rises with the cost of dissent following a failed attempt to split and falls with the cost of forming a new party. Party unity also is predicted to be high when the leadership faction’s weight within the party is large. The model’s results have implications for the relationship between party unity and the majority status of the government party, party system polarization as well as intra-party polarization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

An online appendix with mathematical proofs will be made available as part of this article at https://files.nyu.edu/hm484/public.

In fact, single-party majority governments are not different from explicit coalitions as they both need to maintain a parliamentary majority (Laver 2006).

In the rest of the paper, I use “he” to refer to the minority faction leader and “she” to refer to the party leader.

Patty (2008) also treats party discipline as an endogenous outcome depending on the size of the majority. More specifically, Patty (2008) argues that the strength of the majority party’s leadership in enforcing party discipline is a decreasing function of the majority party’s seat share. Nevertheless, he focuses on the incentives of the majority party leadership to determine its members’ vote choices; whereas here, the focus is on the incentives of the party leader to keep her party united by preventing splits.

In the rest of the paper, R1 and R2 are used to denote both faction leaders and faction/party names.

The case in which R2 has a more extreme preference is discussed below.

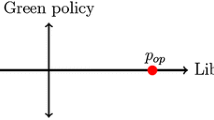

One might ask why R2 would want to challenge R1 in the first place. It is assumed here is that all governments are in equilibrium at the time of their formation following policy bargaining among actors with diverse preferences (Browne et al. 1986). However, over their lifetimes parties face policy shocks, which can change party positions on key policy dimensions, creating conflict among party factions (Laver and Shepsle 1998).

The party leader gets a zero payoff because she can implement her preferred policy and therefore does not experience disutility stemming from the policy distance between her policy position and the resulting policy.

Empirically, this would imply an equitable allocation of ministries, which have jurisdiction over the policy areas for which they are held responsible.

Note that the non-leadership faction is assumed to be pivotal.

Even if the splinter faction is not centrally located, a winning coalition is most likely to be formed between one of the larger parties and the small party (Baron 1991). Another point that needs clarification is that the focus here is on legislative politics and not electoral politics. Electoral politics would affect the expectations about the governments that are likely to form in the event of a split. If, for instance, one actor expects to increase its seat share, this would change the coalition alternatives by making some coalitions more likely than others and therefore affect the probability of a party split. However, the main intuition of the current model would still apply to a model that also takes electoral considerations into account.

The k parameter includes the cost related to the electoral system, but it is meant to capture more than that. In particular, in Eastern European countries, in the early years of 1990, k was small not only because of the permissiveness of the electoral system, but also because none of the existing political parties had time to build name recognition and reputational capital, hence lowering the cost of forming new parties.

It is assumed here that coalition parties will have a proportional say in the government’s policy. This is in fact in line with the prediction of Gamson’s Law, which refers to the strong empirical regularity that the proportion of cabinet ministries received by each government party tends strongly to be equal to the proportion of legislative seats contributed by that party to the government’s seat total (Gamson 1961).

This is analogous to having an indicator function that takes the value 1 when the party leader holds the premiership position, and 0 otherwise.

The formal derivations of the equilibria are presented in the Online Appendix.

Remember that the maximum value that \(\lambda\) can take is 1.

The theoretical model presented in this paper is on single-party majority governments analyzed in the context of two-party systems. In a multi-party system, such as Italy, the coalition formation dynamics following a split are expected to be different, making some coalitions more likely than others and affecting the actors’ actions ex-ante. However, the main intuition of the model’s results extends to multi-party cases since in multi-party systems, as in two-party systems, political competition often takes place between the government’s main party leader (who is usually also the leader of the largest party) and the main opposition party leader (who is also usually the leader of the second largest party) who compete for the prime minister’s position. Comparative data on governments shows that out of the 304 governments formed in 12 advanced industrialized democracies between 1960 and 2005, 242 (\(80\,\%\)) had the largest party’s leader and 38 (\(12\,\%\)) had the second largest party’s leader as the PM (Mutlu-Eren 2010).

Following Ezrow (2007), the polarization variable is measured as the weighted average of the absolute deviations of party positions from the weighted mean of all parties. Alternative measures include Dalton’s polarization measure (Dalton 2008) and the standard deviations of party policies. Party positions are coded using Comparative Manifesto Data (Klingemann et al. 2006).

References

Baron, D. P. (1991). A spatial bargaining theory of government formation in parliamentary systems. American Political Science Review, 85(1), 137–164.

Belloni, F. P., & Beller, D. C. (1976). The study of party factions as competitive political organizations. The Western Political Quarterly, 294, 531–549.

Boucek, F. (2009). Rethinking factionalism: Typologies, intra-party dynamics and three faces of factionalism. Party Politics, 15(4), 455–485.

Bouissou, J. M. (2001). Party factions and the politics of coalition: Japanese politics under the “system of 1955.”. Electoral Studies, 20, 581–602.

Browne, E., Frendreis, J. P., & Gleiber, D. W. (1986). The process of cabinet dissolution: An exponential model of duration and stability in Western democracies. American Journal of Political Science, 30, 628–650.

Carey, J. M. (2007). Competing principals, political institutions, and party unity in legislative voting. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 92–107.

Ceron, A. (2012). Bounded oligarchy: How and when factions constrain leaders in party position-taking. Electoral Studies, 31, 689–701.

Ceron, A. (2015). The politics of fission: An analysis of factional breakaways among Italian parties (1946–2011). British Journal of Political Science, 45(1), 121–139.

Cowley, P., & Norton, P. (1999). Rebels and rebellions: Conservative MPs in the 1992 parliament. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 1(1), 84–105.

Cox, G. W., & McCubbins, M. (2005). Setting the agenda: Responsible party government in the US house of representatives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cox, G. W., & Rosenbluth, F. M. (1995). Anatomy of a split. Electoral Studies, 14, 355–376.

Cox, G. W., Rosenbluth, F. M., & Thies, M. F. (1999). Electoral reform and the fate of factions: The case of Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party. British Journal of Political Science, 29, 22–56.

Dalton, R. J. (2008). The quantity and the quality of party systems: Party system polarization, its measurement, and its consequences. Comparative Political Studies, 41, 899–920.

Desposato, S. W. (2006). Parties for rent? Careerism, ideology, and party switching in Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies. American Journal of Political Science, 50(1), 62–80.

Druckman, J. N. (1996). Party factionalism and cabinet durability. Party Politics, 2(3), 397–407.

Eguia, J. (2011). Endogenous parties in an assembly. American Journal of Political Science, 55(1), 16–26.

Ezrow, L. (2007). The variance matters: How party systems represent the preferences of voters. Journal of Politics, 69(1), 182–192.

Gamson, W. A. (1961). A theory of coalition formation. American Sociological Review, 26(3), 373–382.

Giannetti, D., & Laver, M. (2001). Party system dynamics and the making and breaking of Italian governments. Electoral Studies, 20, 529–553.

Giannetti, D., & Laver, M. (2008). Party cohesion, party discipline, party factions in Italy. In D. Giannetti & K. Benoit (Eds.), Intra-party politics and coalition governments. London: Routledge.

Golder, M. (2003). Electoral institutions, unemployment, and extreme right parties. British Journal of Political Science, 33, 525–534.

Harmel, R., & Tan, A. (2003). Party actors and party change: Does factional dominance matter? European Journal of Political Research, 42, 409–424.

Heller, W. B., & Mershon, C. (2005). Party switching in the Italian Chamber of Deputies, 1996–2001. The Journal of Politics, 67(2), 536–559.

Heller, W. B., & Mershon, C. (2008). Dealing in discipline: Party switching in the Italian Chamber of Deputies, 1998–2000. American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 910–925.

Hix, S. (2002). Parliamentary behavior with two principals: Preferences, parties, and voting in the European Parliament. American Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 688–698.

Hopkin, J. (1999). Party formation and democratic transition in Spain: The creation and collapse of the Union of the Democratic Centre. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Press.

Hortala-Vallve, R., & Mueller, H. (2015). Primaries: The unifying force. Public Choice, forthcoming.

Hug, S. (2001). Altering party systems: Strategic behavior and the emergence of new political parties in Western democracies. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Iaryczower, M. (2006). Contestable leadership: Party leaders as principals and agents. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 3(3), 203–225.

Jackson, M. O., & Moselle, B. (2002). Coalition and party formation in a legislative voting game. Journal of Economic Theory, 103, 49–87.

Kam, C. (2009). Party discipline and parliamentary government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kato, J. (1998). When the party breaks up: Exit and voice among Japanese legislators. American Political Science Review, 92(4), 857–870.

Klingemann, H.-D., Volkens, A., Bara, J., Budge, I., & McDonald, M. (2006). Mapping policy preferences II: Estimates of parties, electors, and governments in Eastern Europe, European Union, and OECD, 1990–2003. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krehbiel, K. (1993). Where’s the party? British Journal of Political Science, 23(1), 253–266.

Krehbiel, K. (2000). Party discipline and measures of partisanship. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 212–227.

Kreuzer, M., & Pettai, V. (2009). Party switching, party systems, and political representation. In W. Heller & C. Mershon (Eds.), Political parties and legislative party switching. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Laver, M. (2006). Legislatures and parliaments. In B. Weingast & D. Wittman (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Laver, M., & Benoit, K. (2003). The evolution of party systems between elections. American Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 215–233.

Laver, M., & Kato, J. (2001). Dynamic approaches to government formation and the generic instability of decisive structures in Japan. Electoral Studies, 20, 509–527.

Laver, M., & Shepsle, K. A. (1998). Events, equilibria, and government survival. American Journal of Political Science, 42(1), 28–54.

Levy, G. (2004). A model of political parties. Journal of Economic Theory, 115, 250–277.

Magaloni, B. (2006). Voting for autocracy: Hegemonic party survival and its demise in Mexico. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mair, P. (1990). The electoral payoffs of fission and fusion. British Journal of Political Science, 20(1), 131–142.

Maor, M. (1995). Intra-party determinants of coalition bargaining. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 7(1), 65–91.

McCarty, H., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2001). The hunt for party discipline in congress. American Political Science Review, 95(3), 673–687.

Morelli, M. (2004). Party formation and policy outcomes under different electoral systems. Review of Economic Studies, 71, 829–853.

Mutlu-Eren, H. (2010). De-selection of Prime ministers by party members. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL.

Patty, J. W. (2008). Equilibrium party government. American Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 636–655.

Rakner, L., Svasand, L., & Khembo, N. S. (2007). Fissions and fusions, foes and friends: Party system restructuring in Malawi in the 2004 general elections. Comparative Political Studies, 40(9), 1123–1137.

Roemer, J. E. (2001). Political competition: Theory and applications. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Schattschneider, E. E. (1942). Party government. New York: Rinehart.

Snyder, J. M., & Ting, M. M. (2002). An informational rationale for political parties. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 90–110.

Tavits, M. (2006). Party system change: Testing a model of new party entry. Party Politics, 12(1), 99–119.

Tavits, M. (2008). Party systems in the making: The emergence and success of new parties in new democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 38(1), 113–133.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Michael Laver, Torun Dewan, Steven Brams, David Stasavage, Kanchan Chandra, and the anonymous referees for extremely helpful comments. A previous version of this manuscript was presented at the 2011 Annual Meeting of the European Political Science Association, Dublin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mutlu-Eren, H. Keeping the party together. Public Choice 164, 117–133 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-015-0277-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-015-0277-4