You load 16 tons and what do you get? Another day older and deeper in debt.

Merle Travis.

Abstract

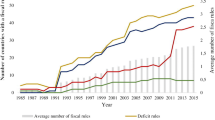

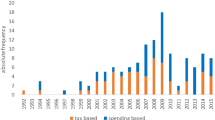

This article employs a duration analysis approach to empirically investigate whether political fractionalization leads to delayed fiscal stabilizations. Using a broad sample of both developed and developing countries for the period 1975–2011, we consistently find strong evidence that political fractionalization is significantly associated with longer delays in stabilizing high deficits. In particular, political fractionalization has a greater impact on delays in periods of macroeconomic distress. We also show that, while the fractionalization of government parties delays fiscal stabilization, the fractionalization of opposition parties tends to facilitate fiscal stabilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Sect. 2 for a more detailed review of the literature.

An important advantage of the duration analysis approach is that it enables us to estimate the effect of political fractionalization on the probability of fiscal stabilizations conditional on being in a high deficit spell. See Sect. 4 for detailed discussions.

Detailed variable definitions, data sources, and their summary statistics are provided in an earlier version of this article available online at http://hye.yolasite.com.

In defining entry into a high deficit spell, we also used 2.5 and 3.5 % as alternative threshold values. In doing so, we identified 307 and 268 fiscal stabilization events within our sample, respectively. We also estimated the benchmark Cox model with high deficit spells identified by these alternative entry criteria and obtained very similar results. Detailed estimation results are reported in the earlier version of this article available online at http://hye.yolasite.com.

Skewness and kurtosis tests strongly reject normality.

While Kontopoulos and Perotti 1999 argue that fractionalization of the fiscal policy decision-making process refers to both legislative fractionalization and executive fractionalization, their empirical evidence suggests that it is legislative fractionalization rather than executive fractionalization that is related more strongly to fiscal outcomes since the 1980s. Since our sample consists of mostly post-1980 observations, our primary measure of political fractionalization focuses on the legislative side of the fiscal decision-making process.

In DPI2012, frac takes the value of one if the legislature comprises independents with no party affiliations. Dropping those observations does not affect our results.

See Henisz (2002) for details on the construction of the political constraint index. The index is subsequently updated by Henisz to 2012.

It is also worth noting that the three countries also differ dramatically in their debt-to-GDP ratios at the entry to their respective high deficit spells. In 2009, the debt-to-GDP ratio is largest in Jordan (61.85 %), the second largest is in El Salvador (49.54 %), and Guatemala’s (23.02 %) is the smallest. The casual observation of a negative relation between the debt-to-GDP ratio at the entry and the duration of high deficit spells from these three cases is borne out in our formal duration analyses.

Following Roubini and Sachs (1989a), we also regressed the change in the debt-to-GDP ratio on its own lag, political fractionalization, a term of interacting fractionalization with lagged debt-to-GDP ratios, and other control variables using OLS. The interaction term in that specification is positive but insignificant.

Because of limited data availability for some covariates, 194 spells are used in the estimation of the benchmark model. The shrinkage in sample size is caused largely caused by entering initial debt as an explanatory variable. If we drop initial debt, we can estimate using 282 spells, and our main results still hold.

Here the marginal impact of a one standard deviation increase in frac on the conditional probability of starting fiscal stabilization is measured by [exp(−0.714 × 0.273) − 1] × 100 %.

We also followed Gunzinger and Sturm (2014) to use the all house variable from the DPI2012 as an inverse measure of political constraint. According to the DPI2012, the all house variable is set to one if the party of the executive has absolute majorities in the one or two legislative chambers having lawmaking powers, and zero otherwise. Although all house is not statistically significant, it does carry the expected positive sign, confirming that fewer political constraints (i.e., less fractionalized legislatures) facilitate fiscal stabilization.

One potential concern over the above analysis is that Greece, Spain and Italy used “creative accounting” to become and continue as Euro members, and their budgetary data on which we rely to identify the timing of entry into and exit from high deficit spells could be less than fully accurate. To address this issue, we excluded these three countries from the sample and re-estimated our benchmark Cox model. Our main results remain unchanged in this exercise.

Detailed results and discussions of these robustness checks are provided in the earlier version of this article available online at http://hye.yolasite.com.

See Terza et al. (2008) for details on the 2SRI method. While not reported here, we also used lagged political fractionalization to alleviate the endogeneity problem in our previous analysis and find that our previous results hold strongly.

References

Alesina, A., Ardagna, S., & Trebbi, F. (2006). Who adjusts and when? On the political economy of reforms. NBER Working Paper No. 12049.

Alesina, A., & Drazen, A. (1991). Why are stabilizations delayed? American Economic Review, 81(5), 1170–1188.

Alesina, A., & Perotti, R. (1997). Fiscal adjustments in OECD countries: Composition and macroeconomic effects. Staff Papers-International Monetary Fund, 44(2), 210–248.

Borrelli, S. A., & Royed, T. J. (1995). Government ‘strength’ and budget deficits in advanced democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 28(2), 225–260.

Cooper, R., Haltiwanger, J., & Power, L. (1999). Machine replacement and business cycle: Lumps and bumps. American Economic Review, 89(5), 921–946.

Cox, D. R. (1975). Partial likelihood. Biometrika, 62(2), 269–276.

De Haan, J., & Sturm, J. (1994). Political and institutional determinants of fiscal policy in the European community. Public Choice, 80(1–2), 57–72.

De Haan, J., & Sturm, J. (1997). Political and economic determinants of OECD budget deficits and government expenditures: A reinvestigation. European Journal of Political Economy, 13(4), 739–750.

De Haan, J., Sturm, J., & Beekhuis, G. (1999). The weak government thesis: Some new evidence. Public Choice, 101(3–4), 163–176.

Dollar, D., & Svensson, J. (2000). What explains the success or failure of structural adjustment programs? The Economic Journal, 110(466), 894–917.

Drazen, A., & Grilli, V. (1993). The benefit of crises for economic reforms. American Economic Review, 83(3), 598–607.

Dunne, T., & Mu, X. (2010). Investment spikes and uncertainty in the petroleum refining industry. Journal of Industrial Economics, 58(1), 190–213.

Edin, P., & Ohlsson, H. (1991). Political determinants of budget deficits: Coalition effects versus minority effects. European Economic Review, 35(8), 1597–1603.

Efron, B. (1977). The efficiency of Cox’s likelihood function for censored data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 72(359), 557–565.

Fabrizio, S., & Mody, A. (2010). Breaking the impediments to budgetary reforms: Evidence from Europe. Economics and Politics, 22(3), 362–391.

Grilli, V., Masciandaro, D., & Tabellini, G. (1991). Political and monetary institutions and public financial policies in the industrial countries. Economic Policy, 6(13), 342–392.

Gunzinger, F., & Sturm, J. (2014). It’s politics, stupid! Political constraints determine governments’ reactions to the great recession. KOF Working papers.

Henisz, W. J. (2002). The institutional environment for infrastructure investment. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(2), 355–389.

Hsieh, C. (2000). Bargaining over reform. European Economic Review, 44(9), 1659–1676.

Kiefer, N. M. (1988). Econometric duration data and hazard functions. Journal of Economic Literature, 26(2), 646–679.

Kontopoulos, Y., & Perotti, R. (1999). Government fragmentation and fiscal policy outcomes: evidence from OECD countries. In J. M. Poterba (Ed.), Fiscal institutions and fiscal performance (pp. 81–102). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mierau, J. O., Jong-A-Pin, R., & de Haan, J. (2007). Do political variables affect fiscal policy adjustment decisions? New empirical evidence. Public Choice, 133(3–4), 297–319.

Padovano, F., & Venturi, L. (2001). Wars of attrition in Italian government coalitions and fiscal performance: 1948–1994. Public Choice, 109(1–2), 15–54.

Perotti, R., & Kontopoulos, Y. (2002). Fragmented fiscal policy. Journal of Public Economics, 86(2), 191–222.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2004). Constitutional rules and fiscal policy outcomes. American Economic Review, 94(1), 25–45.

Roubini, N., & Sachs, J. D. (1989a). Political and economic determinants of budget deficits in the industrial democracies. European Economic Review, 33(5), 903–938.

Roubini, N., & Sachs, J. D. (1989b). Government spending and budget deficits in the industrial countries. Economic Policy, 4(8), 100–132.

Spolaore, E. (1993). Macroeconomic policy, institutions and efficiency. PhD Dissertation, Department of Economics, Harvard University.

Tagkalakis, A. (2009). Fiscal adjustments: do labor and product market institutions matter? Public Choice, 139(3–4), 389–411.

Terza, J. V., Basu, A., & Rathouz, P. J. (2008). Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: Addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. Journal of Health Economics, 27(3), 531–543.

Volkerink, B., & de Haan, J. (2001). Fragmented government effects on fiscal policy: New evidence. Public Choice, 109(3–4), 221–242.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank William F. Shughart II and the referees for their comments. Shu Lin acknowledges financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of China (71222301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grier, K., Lin, S. & Ye, H. Political fractionalization and delay in fiscal stabilizations: a duration analysis. Public Choice 164, 157–175 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-015-0267-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-015-0267-6