Abstract

The mechanism through which outsourcing favourably impacts on workplace performance, particularly productivity, is still unclear. I explore the hypothesis that it does so by impacting workers’ training. I use AWIRS-1995, a matched employer–employee survey that reports ample information on the extent of technology and organizational change in Australian workplaces. I find that there is a positive and significant impact of outsourcing on training when I do not control for the correlation between ununobservable factors in these two binary outcomes. However, once I control for this correlation using a bivariate probit estimator, the training impact of outsourcing becomes negative. I then assess the sensitivity of the outsourcing effect to endogeneity by using the method advocated by Altonji et al. (J Polit Econ 113(1):151–184, 2005) to find that this latter result persists even in the presence of a low correlation between unobservables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Caveats and limitations of this measure of training are discussed in Magnani (2006a).

The relevant question is: “In which of these categories (including technology), does this workplace benchmark?”

Magnani (2006a) finds evidence of a differential effect of technology innovation and technology diffusion of workers’ training.

According to the labour-cost saving hypothesis, an increase in outsourcing could indicate a desire by the firm to save on labour costs, possibly by reducing its training expenses and thus reducing workers’ training opportunities.

The technology standardization hypothesis appeals to explanations such as special expertise possessed by the outside contractor and that are applicable to the hiring firm. For instance, Segal and Sullivan (1997) and Kahn (2000) suggest that, insofar as tasks requiring substantial investment in firm-specific skills are usually ill-suited to the use of temporary workers, technological standardization makes firm-specific knowledge less important and thus shifts upward the demand for outsourced labour services.

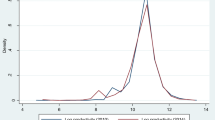

We estimate a large number of specifications for (Contr_up). In the selection of the specification we use to compute the ATT of (Contr_up) on workers’ training we are bound to satisfy the common support requirement and the balancing property requirement.

The CIA states that all relevant differences between the group of workplaces that undergo vertical disintegration and the group of workplaces that do not, are captured by a set of observable characteristics \(\Updelta\), such that the event Y0 is independent from the focal control D, conditional on the propensity p(x), where \(p(x)\equiv \hbox{Pr} (D=1|\Updelta=x)\).

The common support assumption states that in the control group the distribution of the estimated propensity to vertically disintegrate is as similar as possible to the distribution of such propensity in the “treated” group.

The results related to the workplace technology variables are consistent with those already reported in Magnani (2006a).

References

Abraham KG, Taylor SK (1996) Firms’ use of outside contractors: theory and evidence. J Labor Econ 13(3):394–424

Altonji JG, Elder TE, Taber CR (2005) Selection on observed and unoberved variables: assessing the effectiveness of catholic schools. J Polit Econ 113(1):151–184

Antras P, Helpman E (2007) Contractual frictions and global sourcing. CEPR discussion papers 6033, CEPR discussion papers

AWIRS (1997) Technical report. Department of workplace relations and small business, Canberra

Blau DM, Shvydko T (2007) Labor market rigidities and the employment behavior of older workers. IZA discussion paper no. 2996, August

Department of Workplace Relations and Small Business (1997) The 1995 Australian workplace industrial relations survey (AWIRS-1995): employee survey questionnaire [computer file]. Data collected by reark research. Canberra: Social Science Data Archives, The Australian National University [distributor]

Drucker P (1995) Managing in a time of great change. Truman Talley Books Dutton, New York

Geischeker I (2008) The impact of international outsourcing on individual employment security: a micro-level analysis. Labour Econ 15(3):291–314

Greene WH (1998) Gender economics courses in liberal arts colleges: further results. J Econ Educat Fall 29(4):291–300

Greene WH (2008) Econometric analysis, sixth edition, pearson international edition. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Griliches Z (1979) Issues in assessing the contribution of research and development to productivity growth. Bell J Econ 10(1):92–116

Hamermesh DS (2008) Fun with matched firm—employee data: progress and road maps. Labour Econ 15:663–673

Harris R, Siegel D, Wright M (2005) Assessing the impact of management buyouts on economic efficiency: plant-level evidence from the United Kingdom. Rev Econ Stat 87(1):148–153

Hoffman MES (2010) Job losses and perceptions of globalization. J World Trade 44(5):967–983

Houseman S, Kurz C, Lengermann P, Mandel B (2011) Offshoring bias in US Manufacturing. J Econ Perspect 25(2):111–132

Irving P, Steels J, Hall N (2005) Factors affecting the labour market participation of older workers: qualitative research. Research report No 281 Department of Work and Pensions, London

Kahn S (2000) The bottom-line impact of temporary work on companies’ profitability and productivity. In: Francoise C, Ferber MA, Golden L, Herzenberg SA (eds) Nonstandard work: the nature and challenges of emerging employment arangements, Industrial Relations Research Association, New York, pp 235–266

Koskela E, Schob R (2010) Outsourcing of unionized firms and the impact of labor market policy reforms. Rev Int Econ 18(4):682–95

Lynch LM (2007) The adoption and diffusion of organizational innovation: evidence for the U.S economy. NBER working papers 13156. National Bureau of Economic Research, Boston, MA

Magnani E (2006a) Technological diffusion, the diffusion of skill and the gowth of outsourcing in US manufacturing. Econ Innov New Technol 15:617–647

Magnani E (2006b) Technological change and older workers’ training. Int J Econ Policy Stud 1:45–69

Magnani E, Prentice D (2010) Outsourcing and unionization: a tale of misallocated (Resistance) resources. Econ Inq 48(2):460–482

Morrison Paul CJ, Yasar M (2009) Outsourcing, productivity and input composition at the plant level. Can J Econ 42:422–439

Morrison Paul CJ, Siegel D (2001) The impacts of technology, trade and outsourcing on employment and labor composition. Scand J Econ 103(2):241–264

Munch JR, Skaksen JR (2009) Specialization, outsourcing and wages. Rev World Econ 145:57–73

Novak S, Stern S (2007) How does outsourcing affect performance dynamics? Evidence from the automobile industry. July, NBER working paper No. W13235

Organization for economic co-operation and development (OECD) (1998) Work force ageing in OECD countries. In:The OECD employment outlook, OECD Paris, June: 123–151

Rao JNK, Wu CFJ (1988) Resampling inference with complex survey data. J Am Stat Assoc 83(401):231–241

Segal LM, Sullivan DG (1997) The growth of temporary services work. J Econ Perspect 11(2):117–136

Siamesi B (2001) Propensity score matching. United Kingdom stata users’ goup meetings 2001 12, stata users group, revised 23 Aug 2001

Shapiro C, Stiglitz JE (1984) Equilibrium unemployment as a worker discipline device. Am Econ Rev 74(3):433–444

Siegel D (1995) Errors of measurement and the recent acceleration in manufacturing productivity growth. J Prod Anal 6:297–320

Ten Raa T, Wolff EN (2001) Outsourcing of services and the productivity recovery in US manufacturing in the 1980s and 1990s. J Prod Anal 16:213–237

Williams G (2008) Managing by insecurity: work and managerial control under outsourcing. Compet Change 12(3):245–61

Acknowledgments

Thanks to James Chowhan for excellent research assistance. The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge the support of the Canadian Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), which approved this research project and allowed Magnani to work with the Statistics Canada WES dataset (SSHRC Project Number: 281868). Special thanks to Thomas Crossley for his assistance in accessing the WES data. Financial support from the Centre of Excellence for Population Ageing Research (CEPAR), University of New South Wales, and from the Australian Research Council Discovery Project scheme (DP0559431) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Magnani, E. Vertical disintegration and training: evidence from a matched employer–employee survey. J Prod Anal 38, 199–217 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-011-0256-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-011-0256-9