Abstract

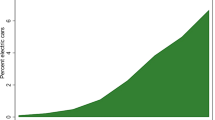

Local governments are increasingly adopting road pricing schemes to curb pollution and congestion in the cities. Despite its popularity, few empirical studies have made an attempt to estimate the effectiveness of such interventions. The aim of this paper is to assess the impact of road pricing on traffic flows by means of a synthetic control approach which allows for a wide heterogeneity of treatment effects. By using a large sample of 75 types of vehicles entering the centre of Milan between 2008 and 2012, we evaluate the enforcement of the road pricing scheme occurred in January 2012 across 20 types of vehicles. We have found a large variation in the reaction of traffic flows and a significant effect in terms of vehicles reduction after pricing for cars and for some types of commercial vehicles. Interestingly and surprisingly, no effect is detected for vehicles whose access in the city centre was forbidden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Residents within the restricted zone were exempted only if driving higher emission standard vehicles while owners of vehicles with older more polluting engines were only given a discount if they bought an annual pass that could cost up to €250 depending on the vehicle’s engine emission standards. Enforcement was carried out through digital cameras located at 43 electronic gates, with fines for offenders varying between €70 and €275.

Percoco (2012) made an attempt at estimating the effect of road pricing on housing price by using a difference-in-difference approach and found that the charge significantly decreased home prices in the treated area, indicating that the negative effect of an increase in transport costs offsets the benefits from a reduction in external costs such as congestion and pollution. This evidence, in particular, confirms the view that the main part of the social surplus is in the toll revenue and as such most motorists had a direct net loss (Eliasson et al. 2009). We thank a referee for pointing out this analogy.

In our case, we had 20 treated vehicles and 55 control types, hence K +1= 74.

In Abadie et al. (2012) the authors show that a regression based approach construct a counterfactual with a linear combination of the untreated units using coefficients that equals one. The difference with the synthetic control is that a regression approach does not restrict the weights to measure between zero and one. By applying negative or larger than one weights, a regression allows for extrapolation beyond the support of comparison units.

Besides public vehicles (police cars, ambulances, buses, etc.), special permits are issued by the municipal police department for health reasons, to journalists, to vehicles bringing construction materials within the charged area, vehicles used by nonprofit firms for social services.

References

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., Hainmueller, J.: Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: estimating the effect of California’s Tobacco Control Program. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 105, 490 (2010)

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., Hainmueller, J.: Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. MIT political science department research paper no. 2011–25, June (2012)

Abadie, A., Gardeazabal, J.: The economic costs of conflict: a case study of the Basque Country. Am. Econ. Rev. 93(1), 112–132 (2003)

AMAT: Valutazione Nuovi Scenari di Regolamentazione degli Accessi alla ZTL Cerchia dei Bastioni. Comune di Milano, Milan (2011)

AMMA: Ecopass - Primi Dati di Marzo. Comune di Milano, Milan (2008a)

AMMA: Monitaraggio indicatori ecopass. Prime Valutazioni, Comune di Milano, Milan (2008b)

AMMA: Sintesi Risultati Conseguiti e Scenari di Sviluppo. Comune di Milano, Milan (2008c)

Banister, D.: Critical pragmatism and congestion charging in London. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 176, 248–264 (2003)

Barnoya, J., Glantz, S.: Association of the California tobacco control program with declines in lung cancer incidence. Cancer Causes Control 15, 689–695 (2004)

Chen, Y., Whalley, W.: Green infrastrucutre: the effects of Urban rail transit on air quality. Am. Econ. J. 4(1), 58–97 (2012)

Davis, L.W.: The effect of driving restrictions on air quality in Mexico city. J. Polit. Econ. 116(1), 38–81 (2008)

Eliasson, J.: A cost-benefit analysis of the Stockholm congestion charging system. Transp. Res. Part A 43(4), 468–480 (2009)

Eliasson, J., Hultkrantz, L., Nerhagen, L.: The Stockholm congestion charging trial 2006: overview of the effects. Transp. Res. Part A 43(3), 240–250 (2009)

Fichtenberg, C.M., Glantz, S.A.: Controlling tobacco use. New Engl. J. Med. 344, 1798–1799 (2001)

Givoni, M.: Re-assessing the results of the London congestion charging scheme. Urban Stud. 49(5), 1089–1105 (2012)

Ieromonachou, P., Potter, S., Warren, J.P.: Norway’s urban toll rings: evolving towards congestion charging. Transp. Policy 13(5), 29–40 (2006)

Ison, S., Rye, T.: Implementing road user charging: the lessons learnt from Hong Kong. Camb. Central Lond., Transp. Rev. 25(4), 451–465 (2005)

Mackie, P.: The London congestion charge: a tentative economic appraisal - a comment on the paper by prud’homme and bocarejo. Transp. Policy 12(3), 288–290 (2005)

Percoco, M.: Urban transport policy and the environment: evidence from Italy. Int. J. Transp. Econ. 37(2), 223–245 (2010)

Percoco, M.: The impact of road pricing on housing prices: preliminary evidence from Milan. Università Bocconi, mimeo (2012)

Percoco, M.: Is road pricing effective in abating pollution? Evidence from Milan, Transp. Res. D, forthcoming (2013a)

Percoco, M.: The effect of road pricing on traffic composition: evidence from a natural experiment in Milan, Italy, Transport Policy, forthcoming (2013b)

Percoco, M.: Regional perspectives on policy evaluation, Springer, forthcoming (2013c)

Prud’homme, R., Bocarejo, J.P.: The London congestion charge: a tentative economic appraisal. Transp. Policy 12(3), 279–287 (2005)

Quddus, M.A., Carmel, A., Bell, M.G.H.: The impact of congestion charge on retail: the London experience. J. Transp. Econ. Policy 41(1), 113–133 (2007)

Raux, C.: Comments on “the London congestion charge: a tentative economic appraisal”. Transp. Policy 12(4), 368–371 (2005)

Rotaris, L., Danielis, R., Marcucci, E., Massiani, J.: The Urban road pricing scheme to curb pollution in Milan, Italy: description, impacts and preliminary cost-benefit Anal- ysis assessment. Transp. Res. A 44, 359–375 (2010)

Santos, G.: Urban congestion charging: a comparison between London and Singapore. Transp. Rev. 25(5), 511–534 (2005)

Santos, G., Bhakar, J.: The impact of London congestion charging scheme on the generalised cost of car commuters to the city of London from a value of travel time Savings perspecitve. Transp. Policy 13(1), 22–33 (2006)

Santos, G., Fraser, G.: Road pricing: lessons from London. Econ. Policy 21(46), 263–310 (2006)

Santos, G., Shaffer, B.: Preliminary results of the London congestion charging scheme. Public Works Manag. Policy 9, 164–168 (2004)

van den Berg, V., Verhoef, E.T.: Winning or losing from dynamic bottleneck congestion pricing? the distributional effects of road pricing with Heterogeneity in values of time and schedule delay. J. Public Econ. 95(7–8), 983–992 (2011)

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Marco Bedogni and Silvia Moroni of AMAT for their guidance through and work with the data. This research was carried out during a visit at LSE Department of Geography and Environment whose hospitality is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Types of vehicles in the sample

Cars: Electric, Euro 0 fuel, Euro 1 fuel, Euro 2 fuel, Euro 3 fuel, Euro 4 fuel, Euro 5 fuel, Euro 0 diesel, Euro 1 diesel, Euro 2 diesel, Euro 3 diesel, Euro 4 diesel, Euro 5 diesel, Euro 0 Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG), Euro 1 LPG, Euro 2 LPG, Euro 3 LPG, Euro 4 LPG, Euro 5 LPG, Euro 4 fuel hybrid, Euro 5 fuel hybrid, Euro 6 fuel hybrid, Euro 4 diesel hybrid, Euro 0 methane, Euro 1 methane, Euro 2 methane, Euro 3 methane, Euro 4 methane, Euro 5 methane.

Vans: Electric, Euro 0 fuel, Euro 1 fuel, Euro 2 fuel, Euro 3 fuel, Euro 4 fuel, Euro 5 fuel, Euro 0 diesel, Euro 1 diesel, Euro 2 diesel, Euro 3 diesel, Euro 4 diesel, Euro 5 diesel, Euro 0 Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG), Euro 1 LPG, Euro 2 LPG, Euro 3 LPG, Euro 4 LPG, Euro 5 LPG, Euro 4 fuel hybrid, Euro 5 fuel hybrid, Euro 6 fuel hybrid, Euro 4 diesel hybrid, Euro 0 methane, Euro 1 methane, Euro 2 methane, Euro 3 methane, Euro 4 methane, Euro 5 methane.

Buses: Electric, Euro 0 fuel, Euro 1 fuel, Euro 2 fuel, Euro 3 fuel, Euro 4 fuel, Euro 5 fuel, Euro 0 diesel, Euro 1 diesel, Euro 2 diesel, Euro 3 diesel, Euro 4 diesel, Euro 5 diesel, Euro 0 Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG), Euro 1 LPG, Euro 2 LPG, Euro 3 LPG, Euro 4 LPG, Euro 5 LPG, Euro 4 fuel hybrid, Euro 5 fuel hybrid, Euro 6 fuel hybrid, Euro 4 diesel hybrid, Euro 0 methane, Euro 1 methane, Euro 2 methane, Euro 3 methane, Euro 4 methane, Euro 5 methane.

Motorbikes

Appendix 2: European emissions standards classification

Emission standards legislation has been imposed for new vehicles sold in Europe since 1992. This applies acceptable limits for exhaust emissions of all new vehicles that are sold in the EU, covering oxides of nitrogen (NOx), hydrocarbons (HC), carbon monoxide (CO) and particulate matter (PM) emissions. The following tables provides Euro classification according to the date of construction of vehicles (see Tables 6 , 7) .

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Percoco, M. Heterogeneity in the reaction of traffic flows to road pricing: a synthetic control approach applied to Milan. Transportation 42, 1063–1079 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-014-9544-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-014-9544-3