Abstract

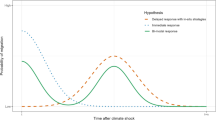

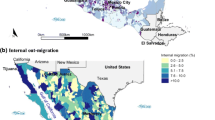

Environmental and climatic changes have shaped human mobility for thousands of years and research on the migration-environment connection has proliferated in the past several years. Even so, little work has focused on Latin America or on international movement. Given rural Mexico’s dependency on primary sector activities involving various natural resources, and the existence of well-established transnational migrant networks, we investigate the association between rainfall patterns and U.S.-bound migration from rural locales, a topic of increasing policy relevance. The new economics of labor migration theory provides background, positing that migration represents a household-level risk management strategy. We use data from the year 2000 Mexican census for rural localities and socioeconomic and state-level precipitation data provided by the Mexican National Institute for Statistics and Geography. Multilevel models assess the impact of rainfall change on household-level international out-migration while controlling for relevant sociodemographic and economic factors. A decrease in precipitation is significantly associated with U.S.-bound migration, but only for dry Mexican states. This finding suggests that programs and policies aimed at reducing Mexico-U.S. migration should seek to diminish the climate/weather vulnerability of rural Mexican households, for example by supporting sustainable irrigation systems and subsidizing drought-resistant crops.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In a report published by the International Organization of Migration (IOM), Kniveton et al. (2008) analyze the association between migration and rainfall using MMP data for the Mexican states of Zacatecas and Durango. A decrease in rainfall is significantly associated with a decrease in international out-migration to the U.S. for Durango, but for Zacatecas this correlation is not significant. However, these results lack reliability, because the study used bivariate associations and a small migrant sample size, and they are therefore not considered in our discussion.

There is also some evidence that in Mexico migration may be associated with sudden-onset events. Using the 2000 Mexican Census, Saldaña-Zorilla and Sandberg (2009) found that local susceptibility to natural disasters is associated with the municipal out-migration rate (which includes both internal and international movement). Here, susceptibility (and the “push” to migrate) included absence of credit and associated declines in income.

The MMP is a collaborative research project based at Princeton University and the University of Guadalajara (PUGU 2010) and provides high-quality data for public use.

We obtained this figure by doing a query at http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/proyectos/bd/consulta.asp?p=14048&c=10252&s=est#, last consulted July 13, 2012.

Our migration measure does not include members of entire households that emigrated abroad during this time (and did not return by the interview date). While this omission could bias our estimates, the amount of error is likely to be small in rural areas, where migrants are more likely to return (Cornelius 1992; Riosmena 2004). In addition, our theoretical framework assumes that the majority of international moves are the result of ex-post/ex-ante household-level responses towards environmental stressors. We are unable to separate such moves from moves that are solely based on economic considerations or motivated by normative expectations of male young adults who might view migration to the U.S. as a rite of passage (e.g., Kandel and Massey 2002). Using a measure of migration that combines all of these various migration motivations can be considered as conservative. We might expect a much stronger relationship for moves solely motivated by risk/insurance considerations and environmental factors.

First, items were included that reflect the physical quality of housing units, in terms of materials used for building the wall, the roof, and the floor; the nature of toilet facilities; the number of rooms in the house; type of sewage disposal; type of water supply (piped vs. nonpiped); cooking fuel (electricity, charcoal, wood, etc.); and whether a hot water heater was available. Second, households were asked to report about the ownership of various means of personal transportation and other household durables—a car, a bicycle, television, radio, videocassette recorder, telephone, refrigerator, and washing machine. These variables were coded on a continuous scale or as dummies, with higher values indicating higher levels of physical capital. All items were used to form a standardized scale with a Cronbach’s α reliability of 0.859.

The index reflects the proportions of a municipality’s households (1) with dirt floors, (2) without indoor plumbing or a toilet, (3) without electricity, (4) without access to piped water, and (5) with more than two people per room, as well as the proportion of adults in the municipality (6) who are illiterate, (7) who have not completed primary education, and (8) who earn less than twice the minimum wage. This measure has been used in other studies of Mexican migration (e.g., Riosmena et al. 2012; Saldaña-Zorilla and Sandberg 2009).

The MOR was calculated as follows: MOR = exp(sqrt(2*σ2)*φ−1(0.75)), where φ(·) is the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1, φ−1(0.75) is the 75th percentile (0.674), exp(·) is the exponential function, and sqrt is the square-root (Larsen and Merlo 2005). The MOR is always greater than or equal to 1. If the MOR is 1, there is no variation between clusters. Large MOR values reflect substantial between-cluster variation. In contrast to the raw variance components, the MOR has the benefit of being directly comparable with the fixed-effects odds ratios. In addition the MOR has a substantively more meaningful interpretation. The MOR quantifies the variation between clusters by comparing two cases from two randomly chosen, different clusters.

The full model was checked for multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF) test. The VIF values for all variables remained smaller than two (except for the interaction and its involved variables). Heuristics suggest that values below 10 indicate that multicollinearity is of no concern.

To investigate whether the non-significant relationship for wet states can be attributed to the impact of Puebla we removed this state from the model. The rainfall decrease coefficient became positive (b = 1.092, z = 0.45) but did not reach significance. Due to convergence issues this model was fitted using the PQL1 instead of PQL2 estimation procedure.

Five robustness tests were performed. First, we used a repeated split sample procedure that randomly divided the sample of dry states (Model A, Table 3) into two groups of equal numbers of households and then ran the multilevel regression for each group separately. This procedure was repeated 150 times, resulting in 300 independent model estimations. We then calculated the mean and standard deviation of the coefficients and z-scores of the dryness increase measure across all iterations. This provides an indication regarding the stability of the parameter estimation when the model is fitted on a random subsample. The mean value of all iterations (b = 1.311) came close to the observed coefficient (b = 1.305), with a relatively small standard deviation (0.029). Also, the mean z-score (2.75) was only slightly smaller than the estimated value (2.84) for Model A, with a standard deviation of 0.25. Even if the standard deviation is subtracted from the mean, the z-score does not drop below the 5 % level, and thus both the rainfall decrease coefficient and its significance can be considered robust.

Second, we ran a jackknife type procedure to test for influential states by removing one state at a time from the sample of dry states in Model A of Table 3 (cf., Ruiter and De Graaf 2006). Regardless of which state was removed from the sample, the rainfall decrease measure remained significant.

Third, we reran Model A after removing the six states that border the U.S.: Baja California del Norte, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, Sonora, and Tamaulipas. It can be expected that emigration behavior in these states is quite different from that in the rest of Mexico owing to the economic and cultural influence of high concentrations of foreign-owned factories (“maquiladoras”) and the lower costs of border crossing (Feng et al. 2010). When these states were removed from the analysis the association remained similar in strength (b = 1.311) and increased in significance (z = 3.51, p < 0.001).

Fourth, it might be argued that our wet/dry classification masks differences in land use or number of people employed in the agricultural sector. To explore this potential problem we performed a group mean comparison (t test) between wet and dry states on major land use categories (forest, crops, pasture in square kilometers, obtained from the MMP supplemental file ENVIRONS) and the percentage of household heads employed as skilled agricultural and fishery workers. Wet and dry states did not differ on land use characteristics. However, a significant difference was detected for occupational categories with a higher percentage of household heads in wet states (48 %) working in the agricultural and fisher sector than in dry states (34 %). We then included the occupation and land-use variables one at a time in the interaction model (Model 4, Table 2) to control for these potentially confounding characteristics. Regardless which variable was included the interaction term between wet/dry areas and rainfall decline stayed significant.

Finally, we investigated the impact of outliers or influential cases on our main finding. Figure 4a reveals that the state of Pueblo constitutes an unusual case, with relatively high migration probability under conditions of substantial rainfall increase. If we remove this state from Models 3 and 4 in Table 2, both the nonlinear term and the interaction term become insignificant, and a significantly positive linear relationship (b = 1.268, p < 0.05) emerges across the remaining 31 Mexican states, in which a decline in rainfall predicts international out-migration. To explain this unique association between substantial out-migration under high levels of precipitation in Pueblo we can speculate that similarly to drought conditions excessive rainfall and associated flooding has detrimental impacts on crop yields. These results, thus, seem to suggest that extreme weather events at both ends of the continuum (wet to dry) and their impact on the agriculture sector may increase international outmigration.

References

Angelucci, M. (2012). U.S. border enforcement and the net flow of Mexican illegal migration. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 60(2), 311–357.

Aparicio, J., & Hidalgo, J. (2004). Water resources management at the Mexican borders. Water International, 29(3), 362–374.

Arias, A. C. S., & Roa, J. C. G. (2008). Instrumental characterization of Colombia’s IDPS: Empirical evidence from the Continuous Household Survey (2001–2006). Revista De Ciencias Sociales, 14(3), 439–452.

Aubee, E., & Hussein, K. (2002). Emergency relief, crop diversification and institution building: The case of sesame in the Gambia. Disasters, 26(4), 368–379.

Baez-Gonzalez, A. D., Chen, P. Y., Tiscareno-Lopez, M., & Srinivasan, R. (2002). Using satellite and field data with crop growth modeling to monitor and estimate corn yield in Mexico. Crop Science, 42(6), 1943–1949.

Baiphethi, M. N., Viljoen, M. F., Kundhlande, G., Botha, J. J., & Anderson, J. J. (2009). Reducing poverty and food insecurity by applying in-field rainwater harvesting (IRWH): How rural institutions made a difference. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 4(12), 1358–1363.

Bardsley, P., Abey, A., & Davenport, S. (1984). The economics of insuring crops against drought. Australian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 28(1), 1–14.

Bardsley, D. K., & Hugo, G. J. (2010). Migration and climate change: Examining thresholds of change to guide effective adaptation decision-making. Population and Environment, 32(2–3), 238–262.

Bates, D. C. (2002). Environmental refugees? Classifying human migrations caused by environmental change. Population and Environment, 23(5), 465–477.

Black, R., Kniveton, D., & Schmidt-Verkerk, K. (2011). Migration and climate change: Towards an integrated assessment of sensitivity. Environment and Planning A, 43(2), 431–450.

Boano, C. (2008). FMO research guide on climate change and displacement. Forced Migration Online (FMO). Retrieved February 28, 2011, from http://www.forcedmigration.org/guides/fmo046/fmo046.pdf.

Bohra, P., & Massey, D. S. (2009). Processes of internal and international migration from Chitwan, Nepal. International Migration Review, 43(3), 621–651.

Booysen, F. (2006). Out-migration in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic: Evidence from the Free State Province. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 32(4), 603–631.

Brooks, N., Chiapello, I., Di Lernia, S., Drake, N., Legrand, M., Moulin, C., et al. (2005). The climate–environment–society nexus in the Sahara from prehistoric times to the present day. Journal of North African Studies, 10(3–4), 253–292.

Brown, S. K., & Bean, F. D. (2006). International migration. In D. Posten & M. Micklin (Eds.), Handbook of population (pp. 347–382). New York: Springer.

BSM. (1998). Migration between Mexico and the United States: Binational study. Mexico City: Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Calavita, K. (1992). Inside the state: The bracero program, immigration, and the I.N.S. New York: Routledge.

Cardoso, L. A. (1980). Mexican emigration to the United States, 1897–1931: Socio-economic patterns. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Carr, D. L., Lopez, A. C., & Bilsborrow, R. E. (2009). The population, agriculture, and environment nexus in Latin America: Country-level evidence from the latter half of the twentieth century. Population and Environment, 30(6), 222–246.

Clark, W. A. V., Deurloo, M. C., & Dieleman, F. M. (2003). Housing careers in the United States, 1968–93: Modelling the sequencing of housing states. Urban Studies, 40(1), 143–160.

Cohen, J. H. (2004). The culture of migration in southern Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Cornelius, W. A. (1992). From sojourners to settlers: The changing profile of Mexican migration to the United States. In J. A. Bustamante, C. W. Reynolds, & R. A. Hinojosa Ojeda (Eds.), U.S.–Mexico relations: Labor market interdependence (pp. 155–195). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Davis, J., & Lopez-Carr, D. (2010). The effects of migrant remittances on population-environment dynamics in migrant origin areas: International migration, fertility, and consumption in highland Guatemala. Population and Environment, 32(2–3), 216–237.

Durand, J., Kandel, W., Parrado, E. A., & Massey, D. S. (1996). International migration and development in Mexican communities. Demography, 33(2), 249–264.

Durand, J., & Massey, D. S. (2003). Clandestinos: Migración México-Estados Unidos en los Albores del Siglo XXI. Zacatecas, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas.

Durand, J., Massey, D. S., & Zenteno, R. M. (2001). Mexican immigration to the United States: Continuities and changes. Latin American Research Review, 36(1), 107–127.

Eakin, H. (2000). Smallholder maize production and climatic risk: A case study from Mexico. Climatic Change, 45(1), 19–36.

Eakin, H. (2005). Institutional change, climate risk, and rural vulnerability: Cases from central Mexico. World Development, 33(11), 1923–1938.

Fan, X. F., & Yakita, A. (2011). Brain drain and technological relationship between skilled and unskilled labor: Brain gain or brain loss? Journal of Population Economics, 24(4), 1359–1368.

Fang, J. Q., & Liu, G. (1992). Relationship between climatic change and the nomadic southward migrations in eastern Asia during historical times. Climatic Change, 22(2), 151–169.

Feng, S. Z., Krueger, A. B., & Oppenheimer, M. (2010). Linkages among climate change, crop yields and Mexico-US cross-border migration. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(32), 14257–14262.

Findley, S. E. (1994). Does drought increase migration? A study of migration from rural Mali during the 1983–1985 drought. International Migration Review, 28(3), 539–553.

Fixico, D. L. (2003). The American Indian mind in a linear world. New York: Routledge.

Franzen, A., & Meyer, R. (2010). Environmental attitudes in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of the ISSP 1993 and 2000. European Sociological Review, 26(2), 219–234.

Fussell, E., & Massey, D. S. (2004). The limits to cumulative causation: International migration from Mexican urban areas. Demography, 41(1), 151–171.

Goldstein, H. (2003). Multilevel statistical models. London: Arnold.

González, J. M., Cháidez, J. J. N., & Ontiveros, V. G. (2008). Análisis de tendencias de precipitación (1920–2004) en México. Investigaciones Geográficas, 65, 38–55.

Gray, C. L. (2009). Environment, land, and rural out-migration in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. World Development, 37(2), 457–468.

Gray, C. L. (2010). Gender, natural capital, and migration in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. Environment and Planning, 42, 678–696.

Gutmann, M. P., & Field, V. (2010). Katrina in historical context: Environment and migration in the US. Population and Environment, 31(1–3), 3–19.

Halliday, T. (2006). Migration, risk, and liquidity constraints in El Salvador. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 54(4), 893–925.

Hamilton, E. R., & Villarreal, A. (2011). Development and the urban and rural geography of Mexican emigration to the United States. Social Forces, 90(2), 661–683.

Hanson, G. H., & Spilimbergo, A. (1999). Illegal immigration, border enforcement, and relative wages: Evidence from apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border. American Economic Review, 89(5), 1337–1357.

Henry, S., Schoumaker, B., & Beauchemin, C. (2004). The impact of rainfall on the first out-migration: A multi-level event-history analysis in Burkina Faso. Population and Environment, 25(5), 423–460.

Hill, K., & Wong, R. (2005). Mexico-US migration: Views from both sides of the border. Population and Development Review, 31(1), 1–18.

Hoefer, M., Rytina, N., & Baker, B. (2012). Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2011. Washington, DC: Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics.

Hoffman, A. (1974). Unwanted Mexican Americans in the Great Depression: Repatriation pressures, 1929–1939. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. (1994). Gendered transitions: The Mexican experience of immigration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hunter, L. M., Murray, S., & Riosmena, F. (2011). Climatic variability and U.S. migration from rural Mexico. Boulder: University of Colorado, Institute of Behavioral Sciences.

INEGI. (1994). Sistema de Cuentas Nacionales de Mexico Producto Interno Bruto por Entidad Federativa 1985 y 1988. Aguascalientes: Instituto Nacional de Estadistica Geografia e Informatica.

INEGI. (2001). Sistema de Cuentas Nacionales de Mexico: Producto Interno Bruto por entidad federativa 1993–2000. Aguascalientes: Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia.

INEGI. (2011). Censo General de Poblacion y Vivienda 1990. Aguascalientes, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia. Retrieved October 31, 2011, from http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/Proyectos/bd/censos/cpv1990/P5.asp?s=est&c=11895&proy=cpv90_p5.

IPCC. (2007). The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: IPCC.

Jones, R. C. (1995). Immigration reform and migrant flows: Compositional and spatial changes in Mexican migration after the Immigration Reform Act of 1986. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 85(4), 715–730.

Jonsson, G. (2010). The environmental factor in migration dynamics—A review of African case studies. Oxford: International Migration Institute, James Martin 21st Century School, University of Oxford.

Juelich, S. (2011). Drought triggered temporary migration in an East Indian village. International Migration, 49, e189–e199.

Kanaiaupuni, S. M. (2000). Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Social Forces, 78(4), 1311–1347.

Kandel, W., & Massey, D. S. (2002). The culture of Mexican migration: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Social Forces, 80(3), 981–1004.

Kandel, W., & Parrado, E. A. (2005). Restructuring of the US meat processing industry and new Hispanic migrant destinations. Population and Development Review, 31(3), 447–471.

Katz, E., & Stark, O. (1986). Labor migration and risk-aversion in less developed countries. Journal of Labor Economics, 4(1), 134–149.

Kniveton, D., Schmidt-Verkerk, K., Smith, C., & Black, R. (2008). Climate change and migration: Improving methodologies to estimate flows. Brighton: International Organization for Migration.

Lamb, H. H. (1995). Climate, history and the modern world. New York: Routledge.

Larsen, K., & Merlo, J. (2005). Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: Integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. American Journal of Epidemiology, 161(1), 81–88.

Lauby, J., & Stark, O. (1988). Individual migration as a family strategy: Young women in the Philippines. Population Index, 54(3), 484–485.

Leckie, G., & Charlton, C. (2011). runmlwin: Stata module for fitting multilevel models in the MLwiN software package. Bristol: Center for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol.

Leiva, A. J., & Skees, J. R. (2008). Using irrigation insurance to improve water usage of the Rio Mayo irrigation system in northwestern Mexico. World Development, 36(12), 2663–2678.

Lindstrom, D. P. (1996). Economic opportunity in Mexico and return migration from the United States. Demography, 33(3), 357–374.

Lindstrom, D. P., & Lauster, N. (2001). Local economic opportunity and the competing risks of internal and US migration in Zacatecas, Mexico. International Migration Review, 35(4), 1232–1256.

Lindstrom, D. P., & Ramirez, A. (2010). Pioneers and followers: Migrant selectivity and the development of U.S. migration streams in Latin America. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 630, 53–77.

Liverman, D. M. (1990). Drought impacts in Mexico: Climate, agriculture, technology, and land tenure in Sonora and Puebla. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 80(1), 49–72.

Lucas, R. E. B., & Stark, O. (1985). Motivations to remit: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy, 93(5), 901–918.

Martin, P., & Midgley, E. (2010). Immigration in America 2010. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

Massey, D. S. (1987). Understanding Mexican migration to the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 92(6), 1372–1403.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466.

Massey, D. S., Axinn, W. G., & Ghimire, D. J. (2010). Environmental change and out-migration: Evidence from Nepal. Population and Environment, 32(2–3), 109–136.

Massey, D. S., Durand, J., & Malone, N. J. (2002). Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican immigration in an era of economic integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, D. S., & Espinosa, K. E. (1997). What’s driving Mexico-US migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 102(4), 939–999.

Massey, D. S., Goldring, L., & Durand, J. (1994). Continuities in transnational migration: An analysis of nineteen Mexican communities. American Journal of Sociology, 99(6), 1492–1533.

Massey, D. S., & Parrado, E. (1994). Migradollars: The remittances and savings of Mexican migrants to the USA. Population Research and Policy Review, 13(1), 3–30.

Massey, D. S., & Riosmena, F. (2010). Undocumented migration from Latin America in an era of rising U.S. enforcement. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 630, 294–321.

Mberu, B. U. (2006). Internal migration and household living conditions in Ethiopia. Demographic Research, 14, 509–539.

McKenzie, D. J. (2006). The consumer response to the Mexican peso crisis. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 55(1), 139–172.

McLeman, R., Herold, S., Reljic, Z., Sawada, M., & McKenney, D. (2010). GIS-based modeling of drought and historical population change on the Canadian prairies. Journal of Historical Geography, 36(1), 43–56.

McLeman, R. A., & Hunter, L. M. (2010). Migration in the context of vulnerability and adaptation to climate change: Insights from analogues. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Climate Change, 1(3), 450–461.

McLeman, R., & Smit, B. (2006). Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Climatic Change, 76(1–2), 31–53.

Meze-Hausken, E. (2000). Migration caused by climate change: How vulnerable are people in dryland areas? Migration and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 5(4), 379–406.

Montgomery, M. R., Gragnolati, M., Burke, K. A., & Paredes, E. (2000). Measuring living standards with proxy variables. Demography, 37(2), 155–174.

MPC. (2011). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 6.1. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota.

Munshi, K. (2003). Networks in the modern economy: Mexican migrants in the US labor market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(2), 549–599.

Myers, N. (2002). Environmental refugees: A growing phenomenon of the 21st century. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B—Biological Sciences, 357(1420), 609–613.

Myers, N. (2005). Environmental refugees: An emergent security issue. Prague: 13th Economic Forum, Session III—Environment and Migration.

Orrenius, P. M., & Zavodny, M. (2003). Do amnesty programs reduce undocumented immigration? Evidence from IRCA. Demography, 40(3), 437–450.

Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. V. (2011). Unauthorized immigrant population: National and state trends, 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology, 36(4), 859–866.

PUGU. (2010). Mexican Migration Project. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University and University of Guadalajara. Retrieved December 1, 2010, from http://mmp.opr.princeton.edu.

Rasbash, J., Charlton, C., Browne, W. J., Healy, M., & Cameron, B. (2009). MLwiN Version 2.1. Bristol, UK: Center for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol.

Riosmena, F. (2004). Return versus settlement among undocumented Mexican migrants, 1980 to 1996. In J. Durand & D. S. Massey (Eds.), Crossing the border: Research from the Mexican Migration Project (pp. 265–280). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Riosmena, F. (2009). Socioeconomic context and the association between marriage and Mexico-US migration. Social Science Research, 38(2), 324–337.

Riosmena, F., Frank, R., Akresh, I., & Kroeger, R. A. (2012). U.S. migration, translocality, and the acceleration of the nutrition transition in Mexico. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102(5), 1–10.

Riosmena, F., & Massey, D. S. (2012). Pathways to El Norte: Origins and characteristics of recent Mexican migrants to new U.S. destinations. International Migration Review, 46(1), 3–36.

Rosenzweig, M. R., & Stark, O. (1989). Consumption smoothing, migration, and marriage: Evidence from rural India. Journal of Political Economy, 97(4), 905–926.

Ruggles, S., King, M. L., Levison, D., McCaa, R., & Sobek, M. (2003). IPUMS—International. Historical Methods, 36(2), 60–65.

Ruiter, S., & De Graaf, N. D. (2006). National context, religiosity, and volunteering: Results from 53 countries. American Sociological Review, 71(2), 191–210.

Saenz, R., & Morales, M. C. (2006). Demography of race and ethnicity. In D. L. Poston & M. Micklin (Eds.), Handbook of population (pp. 169–208). New York: Springer.

Saldaña-Zorrilla, S. O., & Sandberg, K. (2009). Spatial econometric model of natural disaster impacts on human migration in vulnerable regions of Mexico. Disasters, 33(4), 591–607.

Sana, M., & Massey, D. S. (2005). Household composition, family migration, and community context: Migrant remittances in four countries. Social Science Quarterly, 86(2), 509–528.

Schwartz, M. L., & Notini, J. (1994). Desertification and migration: Mexico and the United States. San Francisco: U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform.

Shen, S., & Gemenne, F. (2011). Contrasted views on environmental change and migration: The case of Tuvaluan migration to New Zealand. International Migration, 49, e224–e242.

Shiferaw, B. A., Kebede, T. A., & You, L. (2008). Technology adoption under seed access constraints and the economic impacts of improved pigeon pea varieties in Tanzania. Agricultural Economics, 39(3), 309–323.

Smeal, D., & Zhang, H. (1994). Chlorophyll meter evaluation for nitrogen management in corn. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 25(9), 1495–1503.

Smith, S. K., & McCarty, C. (2009). Fleeing the storm(s): An examination of evacuation behavior during Florida’s 2004 hurricane season. Demography, 46(1), 127–145.

Solomon, S., Plattner, G. K., Knutti, R., & Friedlingstein, P. (2009). Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(6), 1704–1709.

Stahle, D. W., Cook, E. R., Villanueva Diaz, J., Fye, F. K., Burnette, D. J., Griffin, R. D., et al. (2009). Early 21st-century drought in Mexico. EOS Transactions of the American Geographical Union, 90(11), 89–100.

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. E. (1985). The new economics of labor migration. American Economic Review, 75(2), 173–178.

Stark, O., & Levhari, D. (1982). On migration and risk in LDCs. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 31(1), 191–196.

Stark, O., & Taylor, J. E. (1991). Migration incentives, migration types: The role of relative deprivation. Economic Journal, 101(408), 1163–1178.

Stern, N. (2007). Economics of climate change: The Stern review. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Suhrke, A. (1994). Environmental degradation and population flows. Journal of International Affairs, 47(2), 473–496.

Takenaka, A., & Pren, K. A. (2010). Determinants of emigration: Comparing migrants’ selectivity from Peru and Mexico. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 630, 178–193.

Taylor, J. E. (1987). Undocumented Mexico-U.S. migration and the returns to households in rural Mexico. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 69(3), 626–638.

Taylor, J. E. (1999). The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration, 37(1), 63–88.

Taylor, J. E., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Massey, D. S., & Pellegrino, A. (1996). International migration and national development. Population Index, 62(2), 181–212.

Thomas, D. S. G., & Twyman, C. (2006). Adaptation and equity in resource dependent societies. In W. N. Adger, J. Paavola, S. Huq, & M. J. Mace (Eds.), Fairness in adaptation to climate change (pp. 223–237). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Todaro, M. P. (1976). Internal migration in developing countries. Geneva: International Labor Office.

Todaro, M. P., & Maruszko, L. (1987). Illegal migration and US immigration reform: A conceptual framework. Population and Development Review, 13, 101–114.

Trenberth, K. E., Jones, P. D., Ambenje, P., Bojariu, R., Easterling, D., Klein Tank, A., et al. (2007). Observations: Surface and atmospheric climate change. In S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. B. Averyt, M. Tignor, & H. L. Miller (Eds.), Climate change 2007: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tyson, P. D., Lee-Thorp, J., Holmgren, K., & Thackeray, J. F. (2002). Changing gradients of climate change in Southern Africa during the past millennium: Implications for population movements. Climatic Change, 52(1–2), 129–135.

VanGeel, B., Buurman, J., & Waterbolk, H. T. (1996). Archaeological and palaeoecological indications of an abrupt climate change in The Netherlands, and evidence for climatological teleconnections around 2650 BP. Journal of Quaternary Science, 11(6), 451–460.

Vasquez-Leon, M., West, C. T., & Finan, T. J. (2003). A comparative assessment of climate vulnerability: Agriculture and ranching on both sides of the US-Mexico border. Global Environmental Change: Human and Policy Dimensions, 13(3), 159–173.

Warner, K., Erhart, C., de Sherbinin, A., Adamo, S., & Chai-Onn, T. (2009). In search of shelter: Mapping the effects of climate change on human migration and displacement. Chatelaine: CARE International.

Warner, K., Hamza, M., Oliver-Smith, A., Renaud, F., & Julca, A. (2010). Climate change, environmental degradation and migration. Natural Hazards, 55(3), 689–715.

White, M. J., & Lindstrom, D. P. (2006). Internal migration. In D. Poston & M. Micklin (Eds.), Handbook of population (pp. 311–346). New York: Kluwer.

Wiggins, S., Keilbach, N., Preibisch, K., Proctor, S., Herrejon, G. R., & Munoz, G. R. (2002). Agricultural policy reform and rural livelihoods in central Mexico. Journal of Development Studies, 38(4), 179–202.

Winters, P., Davis, B., & Corral, L. (2002). Assets, activities and income generation in rural Mexico: Factoring in social and public capital. Agricultural Economics, 27(2), 139–156.

Zeuli, K. A., & Skees, J. R. (2005). Rainfall insurance: A promising tool for drought management. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 21(4), 663–675.

Acknowledgments

This project received funding and administrative support from the University of Colorado Population Center (NICHD R21 HD051146). Special thanks to three anonymous reviewers for insightful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this manuscript. We express our thanks to Nancy D. Mann for her careful editing and helpful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nawrotzki, R.J., Riosmena, F. & Hunter, L.M. Do Rainfall Deficits Predict U.S.-Bound Migration from Rural Mexico? Evidence from the Mexican Census. Popul Res Policy Rev 32, 129–158 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-012-9251-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-012-9251-8