Abstract

In presidential nomination campaigns, individual state primaries and a national competition take place simultaneously. The relationship between divisive state primaries and general election outcomes is substantially different in presidential campaigns than in single-state campaigns. To capture the full impact of divisiveness in presidential campaigns, one must estimate both the impact of national party division (NPD) and the impact of divisive primaries in individual states. To do so, we develop a comprehensive model of state outcomes in presidential campaigns that incorporates both state-level and national-level controls. We also examine and compare several measures of NPD and several measures of divisive state primaries found in previous research. We find that both NPD and divisive state primaries have independent and significant influence on state-level general election outcomes, with the former having a greater and more widespread impact on the national results. The findings are not artifacts of statistical techniques, timeframes or operational definitions. The results are consistent—varying very little across a wide range of methods and specifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A national party can have a set of divisive state primaries yet remain united (e.g., 2000 Republicans). Alternatively, a party could be divided nationally yet see few divisive state primaries, especially if “divisive” is operationalized as a small victory margin. One candidate could win handily in some regions while losing by large margins in others (e.g., 1976 Republicans). In some elections there are numerous divisive state primaries yet the national party is able to unite during the general election campaign (e.g., 1976 Democrats, 1980 Republicans). In some elections there are few divisive primaries, yet the national party is severely divided at the convention and beyond (e.g., 1964 Republicans). Some state primaries are not even contested since they occur after the nomination has effectively been decided.

Studies of subnational divisive primaries have reached a confusing variety of conclusions (Lengle and Owen 1996). Several found that such primaries negatively affect general election outcomes (e.g., Bernstein 1977), others found mixed effects (Born 1981; Kenney and Rice 1984), others found little or no effect (Hacker 1965; Kenney 1988), and some found a positive effect in the out-party (Westlye 1991; Partin 2002). Jacobson’s (1978) work on congressional elections helps to make sense of these results. A congressional or gubernatorial incumbent whose reelection chances are relatively low may be challenged within his or her own party, leading to a (potentially) divisive primary that hurts the incumbent in the general election. On the other hand, challengers typically are not well-known—a primary battle in the out-party

brings media attention to the candidates in that party and thus raises their name recognition, a valuable resource in a congressional or gubernatorial race (Westlye 1991; Lazarus 2005).

The nature of single-state primaries in presidential campaigns is dramatically different. Unlike sub-national primaries, candidates may or may not choose to compete vigorously in certain states. Thus it is possible for a number of presidential state primaries to be non-divisive (if it is clear which candidate is likely to win that state) even though the national campaign may be highly competitive. For example, in 1980 few Democratic state primaries were competitive; most were assumed to be easy victories for one candidate or the other and thus not seriously contested. Conversely, it is possible for there to be a number of divisive state primaries even though the result of the national campaign is not really in doubt. In 1976, for example, most non-Southern primary were seriously contested, yet the national Democratic party did not suffer substantial internal divisions and quickly united behind Jimmy Carter once the primaries ended.

The divisive primary hypothesis is rooted in cognitive psychology, but there are several behavioral explanations that could cause the phenomenon. Voters may rationally use divisiveness as a cue for low candidate quality. One could hypothesize a divisiveness effect without making strong assumptions about voter rationality.

For example, voters in Iowa and New Hampshire usually can choose among 5–9 potentially viable candidates; after Iowa and New Hampshire the field typically narrows to 2 or 3 viable candidates because the unsuccessful candidates withdraw. Thus the choices of voters in subsequent states is restricted.

State party resources are rarely used during primary battles, whether subnational or presidential, rather resources come from the individual candidate campaigns.

Economic and other national contextual variables are adjusted to account for the party of the incumbent president.

After the mid-1970s, the second dimension is best characterized as reflecting “social issues” such as abortion, busing, and gun control. (Poole, Keith; 2015; interview with author)

As a test for possible realignment effects, the model was re-estimated with a dummy for the post-1968 period; the dummy is not significant and its inclusion barely alter the coefficients.

There is some collinearity between the national economy and national party division (r = .67). A weak economy is often associated with divisions within the incumbent party. If the economic variable was excluded from the model, it would bias the coefficient of national party division, probably by artificially inflating the estimated impact of that variable.

For example, there were roughly as many out-party candidates in the primaries opposing popular incumbents such as Reagan and Bill Clinton as there were opposing unpopular incumbents such as Ford and Carter. Similarly, the two most popular incumbents running in the past 50 years were Nixon and Reagan; both faced several strong candidates in the other party (Muskie, Humphrey, Wallace and Scoop Jackson in 1972; Mondale and John Glenn in 1984).

In-party challenges to an incumbent president are rare. During the 1948–2012 period, nine incumbents faced no serious challenge in the primaries; only two (Ford and Carter) were challenged (though some would not classify Ford as a true incumbent). The case of Johnson in 1968 is open to interpretation—Johnson was challenged but withdrew early (1968 is not included in our dataset).

Results are substantively similar if July approval ratings are used.

We believe that war, as measured by casualties, is a national-level phenomenon. Certainly there are variations across states during wartime but we believe that the difference between wartime and peacetime has a greater effect on the electorate than do variations across states. We tested state-level war deaths and found it was not statistically significant. It should be noted however that Karol and Miguel (2007) found state-level war casualties to be significant in their analysis of the 2004 election.

To account for the possibility of serial correlation, the model was also estimated with Baltagi and Wu’s (1999) GLS estimator for AR(1) panel data and OLS with a lagged dependent variable and Panel Corrected Standard Errors (Beck and Katz 1996); both yield substantively similar results to those presented in the text. (See table A-1, online appendix)

A possible problem arises in that the statistical model assumes a continuous and unbounded dependent variable. While the general election outcome is indeed continuous, a proportion is, by definition, bounded. Paolino (2001) shows that when there are many cases close to the bounds (in this case 0 and 1), there are substantial benefits to using a maximum likelihood model for beta-distributed dependent variables. However, in this dataset there are no cases within .19 of the bounds and only 9 cases (about 1.2 %) within .25 of the bounds. As such, the gains from a beta-distributed dependent variable model would be minimal. Indeed, Paolino’s replication of Atkeson (1998) uses a similar dependent variable and shows no difference between a model assuming an unbounded dependent variable and the beta-distributed dependent variable model.

Since the McGovern–Fraser reforms dramatically changed the nature of nomination campaigns, the model was also applied only to the elections of 1972–2012.

Both the divisive state primary measure and the national party division measure in 1968 are anomalous. The nomination phase is unique in that one of the two leading candidates, Robert Kennedy, was assassinated before the convention, thus likely altering the impact of divisive state primaries on general election results. Also, Hubert Humphrey entered no primaries, thus every primary shows up as extremely divisive. The general election results are also anomalous because of the strong performance of a non-centrist third party candidate (see online appendix). Although we decided to exclude 1968 from the analysis, we tested the model with 1968 included. The parameter estimates for national party division and divisive state primaries were essentially unchanged (see online Table A-1).

Two cases were excluded because neither the Democratic candidate nor electors pledged to him appeared on the ballot (Mississippi in 1960, Alabama in 1964). One was excluded because it was an extreme outlier (Johnson received less than 13 % in Mississippi in 1964). These outlying cases could bias the parameter estimates (Achen 1982).

The Democrats lacked an early dominant frontrunner in 1976 and 1992, yet the party was relatively united by convention time. The 1972 and 1984 Democratic campaigns both had dominant early frontrunners, yet the party was divided and lost the general election. Typically we observe five to nine candidates in a presidential nomination contest that does not include an in-party incumbent; some of these campaigns lead to a divided national party; others do not.

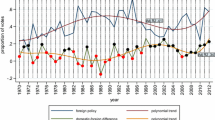

This research focuses on the potential negative impact of short-term national party division on that year’s general election. It is important to differentiate between preexisting national party division (before the primaries) and national party division when it is most likely to impact general election results (during the primaries, at the convention, and beyond). The existence of long-term underlying division is not sufficient to hurt a party’s general election vote. Rather, the harm becomes manifest when there is intense competition for the party’s nomination and the nominee is unable to unite the party. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, there were severe long-term divisions in the Democratic party while the Republican party was much more united. Nonetheless, in 1964 and 1976, the Democrats were mostly united and the Republicans seriously divided.

Aggregate primary vote gets around the problem of stage-managed conventions but it is not a good measure for the pre-reform period. Fifty years ago, less than a third of the states used primaries (rather than caucuses), and many of them were either “delegate primaries”, “favorite son” or “beauty contest” primaries. Nowadays, more than two-thirds of states use primaries, delegates are generally bound or committed to vote for a particular candidate.

Primaries vary in many ways (timing, winner-take-all vs. proportional representation, open vs. closed, number of candidates, turnout, etc.). Although each of these is potentially related to divisiveness and thus reflected in our parameter estimates, we recognize that timing and the number of candidates (and possibly turnout) could cause some divisive state primaries to have greater or lesser impact on general election results than others. We address these concerns in the online appendix.

Comparing the consequences of a 1-unit change in DSP with a 1-unit change in NPD may not be a fair comparison. It may be that changing DSP is “easy” while changing NPD is “hard”. In nomination campaigns, party leaders try to unify the national party as soon as possible; at the state level, candidates try to stay active, run in primaries and defeat opponents. It's easy to get national party unity when there's a popular incumbent running; it's hard to do so when there are several strong candidates representing different factions. It's easier to get high divisiveness scores when one party has selected its nominee and the other has not; it's harder to do so after both parties have selected their nominees (see online appendix).

In this research, we seek to show that the full impact of divisiveness in presidential elections involves both state primary divisiveness and national party division. A model of election outcomes that does not include the latter is misspecified; thus the estimate of state primary divisiveness is potentially biased (see Table A-1 online).

The coefficients of divisive state primaries measured in terms of support for the eventual nominees and by victory margin are not comparable because they are measured on different scales. Nonetheless, the former are statistically significant while the latter are not.

The potential for deleterious effects is greatest when nomination candidates differ ideologically and regionally, as was the case in the 1980 Democratic campaign. In 2008, the Obama–Clinton struggle did not prevent the party from winning the general election. However, we specifically test the effects of state and national party division in 2008. First, two interactive variables were created to see if the impact of divisive state primaries or national party division was different in 2008 than in other elections. Neither was significant, indicating no discernible difference in the impact of divisiveness in 2008. Similarly, estimating the analysis without 2008 produced nearly identical parameter estimates indicating that the 2008 election results fit the general pattern seen in previous elections. Other researchers reached similar conclusions (Henderson et al 2010; Makse and Sokhey 2010; Southwell 2010; but see Wichowsky and Niebler 2010).

The analysis shows that state general election outcomes are influenced by both long-term and short-term factors and by both national-level and state-level factors. Among the state-level factors, state partisanship and both state ideology variables are statistically significant. A state in which the average previous congressional and gubernatorial Democratic vote was 60 %, for example, would tend to have more than a 2 % higher presidential vote than a state with 50 % previous Democratic vote. The difference in the presidential vote between a very moderate state and a state with the most extreme general ideology score would be approximately 7–8 %. The corresponding civil rights/social issues ideology difference would be 4 %. In addition, a presidential candidate tends to receive about 3 % more in his home state than would otherwise be expected.

References

Achen, C. (1982). Interpreting and using regression. Beverly Hills: Sage.

America Votes, 1996–2004. Government Affairs Institute, CQ Inc., Washington D.C., v. 22–26.

Atkeson, L. R. (1998). Divisive primaries and general election outcomes: Another look at presidential campaigns. American Journal of Political Science, 42, 256–271.

Baltagi, B. H. (2005). Econometric analysis of panel data (3rd ed.). Wiley: Hoboken.

Baltagi, B. H., & Wu, P. X. (1999). Unequally spaced panel data regressions with AR(1) disturbances. Econometric Theory, 15, 814–823.

Bartels, L., & Zaller, J. (2001). Presidential vote models: A recount. P.S Political Science and Politics, 34, 9–20.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1996). Nuisance vs. substance: Specifying and estimating time-series-cross-section models. Political Analysis, 6(1), 1–36.

Bernstein, R. A. (1977). Divisive primaries do hurt: U.S. Senate races, 1956-1972. American Political Science Review, 71, 540–545.

Born, R. (1981). The influence of house primary election divisiveness on general election margins, 1962-76. Journal of Politics, 43, 640–661.

Campbell, J. (1992). Forecasting the presidential vote in the states. American Journal of Political Science, 36, 386–407.

Campbell, J. (2000). The American campaign: U.S. presidential campaigns and the national vote. College Station: Texas A&M Press.

Campbell, J. (2001). The referendum that didn’t happen: The forecasts of the 2000 presidential election. P.S Political Science and Politics, 34, 33–38.

Campbell, J. (2004). Nomination politics, party unity, and presidential elections. In J. Pfiffner & R. Davidson (Eds.), Understanding the Presidency (4th ed.). New York: Longman.

Congressional Quarterly. Guide to U.S. elections, 3rd edition.

Echols, M. T., & Ranney, A. (1976). The impact of interparty competition reconsidered: The case of Florida. Journal of Politics, 38, 142–152.

Erikson, R. S., Gerald, C. W., & John, P. M. (1993). Statehouse democracy: Public opinion and policy in the American states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gelman, A., & King, G. (1993). Why are American presidential election campaign polls so variable when votes are so predictable? British Journal of Political Science, 23, 409–451.

Hacker, A. (1965). Does a divisive primary harm a candidate’s election chances? American Political Science Review, 59, 105–110.

Henderson, M., Sunshine Hillygus, D., & Thompson, T. (2010). Sour grapes or rational voting. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74(3), 499–529.

Herrera, R. (1993). Cohesion at the party conventions. Polity, 26, 75–89.

Holbrook, T. M. (1991). Presidential elections in space and time. American Journal of Political Science, 35, 91–109.

Holbrook, T. M. (1996). Do campaigns matter? Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Jackson, R. A., & Carsey, T. M. (1999). Presidential voting across the American states. American Politics Quarterly, 27, 379–402.

Jacobson, G. (1978). The effects of campaign spending in congressional elections. American Political Science Review, 72(2), 469–491.

Jacobson, G., & Kernell, S. (1981). Strategy and choice in congressional elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Karol, D., & Miguel, E. (2007). The electoral cost of war: Iraq casualties and the 2004 U.S. presidential election. Journal of Politics, 69, 633–648.

Kenney, P. J., & Rice, T. W. (1984). The effect of primary divisiveness in gubernatorial and senatorial elections. Journal of Politics, 46, 904–915.

Kenney, P. J., & Rice, T. W. (1987). The relationship between divisive primaries and general outcomes. American Journal of Political Science, 31, 31–44.

Key, V. O. (1953). Politics, parties and pressure groups. New York: Thomasy Crowell.

Lazarus, J. (2005). Unintended consequence: Anticipation of general election outcomes and primary election divisiveness. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 30, 3.

Lengle, J. I., & Owen, D. (1996). Studying divisive primaries. Presented to the Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association, Atlanta, Georgia.

Lengle, J. I., Owen, D., & Sonner, M. (1995). Divisive nominating mechanisms and democratic party electoral prospects. Journal of Politics, 57, 370–383.

Makse, T., & Sokhey, A. (2010). Revisiting the divisive primary hypothesis. American Politics Research, 38(2), 233–265.

Mayer, W. G. (1996). The divided Democrats. Boulder: Westview Press.

McCarty, N., Poole, K., & Rosenthal, H. (2006). Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. Cambridge: MIT Press.

N.E.S. website at www.umich.edu/~nes/nesguide.

Norpoth, H. (2001). Primary colors: A mixed blessing for Al Gore. PS Political Science and Politics, 34, 45–48.

Paolino, P. (2001). Maximum likelihood estimation of models with beta-distributed dependent variables. Political Analysis, 9, 325–346.

Partin, R. (2002). Assessing the impact of campaign spending in governors’ races. Political Research Quarterly, 55, 213–233.

Poole, Keith T., & Rosenthal, Howard. (1997). A political-economic history of roll call voting. New York: Oxford University Press.

Poole, K.T. website: http://voteview.com/dwnl.htm.

Rabinowitz, G., Gurian, P.-H., & MacDonald, S. E. (1984). The structure of presidential elections and the process of realignment, 1944-1980. American Journal of Political Science, 28, 611–635.

Rosenstone, S. J. (1983). Forecasting presidential elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Southwell, P. (1986). The politics of disgruntlement: Nonvoting and defection among supporters of nomination losers, 1968–1984. Political Behavior, 8, 85–91.

Southwell, P. (2010). The effect of nomination divisiveness on the 2008 presidential election. PS Political Science and Politics, 43(2), 255–258.

State Personal Income, 1929-2000. 2000. U.S. Department of Commerce. Washington D.C. Statistical Abstract of the United States. 1984, 1990, 1995, 1999. U.S. Census Bureau, D.C

Steger, W. P. (2008). Interparty differences in elite support for presidential nomination candidates. American Politics Research, 36(5), 724–749.

Stimson, J. A. (1985). Regression in time and space: A statistical essay. American Journal of Political Science, 29(4), 914–947.

Westlye, H. C. (1991). Senate elections and campaign intensity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wichowsky, A., & Neibler, S. (2010). Narrow victories and hard gains. American Politics Research, 38(6), 1052–1071.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gurian, PH., Burroughs, N., Atkeson, L.R. et al. National Party Division and Divisive State Primaries in U.S. Presidential Elections, 1948–2012. Polit Behav 38, 689–711 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9332-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9332-1