Abstract

In contrast to what we know about the sources of political trust among whites, recent research suggests that political mistrust among blacks indicates discontent with the political system. The current study adds to research investigating racial differences in political trust by examining racial differences in the influence of the 2000 United States presidential election on political trust. Specifically, I test for whether whites and blacks adjusted their trust in government in response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush versus Gore (2000) and whether the influence of the Court’s decision on trust was dependent on partisan identification. The findings indicate that blacks perceived the Court’s decision as illegitimate, reinforcing their mistrust in their political system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Specifically, there are 474 black Republican interviewed before the Bush versus Gore decision and 23 interviewed after the decision. Likewise, there are 520 black independents interviewed before the decision and 25 interviewed after the decision.

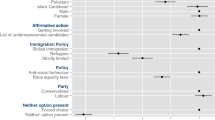

The racial differences in effects of predictors of political trust were estimated by including interaction terms between race and all other independent variables (see Appendix B).

I also set all dummy variables at their means, which is substantively meaningless but representative of their “average” value.

One potential concern when comparing predicted probabilities of political trust across race, partisanship, and interview period is that there are small numbers of black Republicans and Independents in the post-Bush versus Gore period, making the assumption that these comparisons are normally distributed tenuous. However, this is not a concern in this case because Clarify uses simulations based on repeated (in this case 1,000) draws from the data. Thus, estimates of predicted probabilities and standard errors are based on a much larger number of (simulated) cases than actually exist in the dataset.

References

Avery, J. M. (2006). The sources and consequences of political mistrust among African Americans. American Politics Research, 34, 655–682.

Citrin, J. (1974). Comment: The political relevance of trust in government. American Political Science Review, 68, 973–988.

Citrin, J., & Luks, S. (2001). Political trust revisited: Déjà Vu all over again? In J. R. Hibbing, & E. Theiss-Morse (Eds.), What is it about government that Americans dislike? New York: Cambridge University Press.

Easton, D. (1965). A systems analysis of political life. New York: Wiley.

Gurin, P., & Epps, E. (1975). Black consciousness, identify and achievement. New York: John Wiley.

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The political relevance of political trust. American Political Science Review, 92, 791–808.

Hetherington, M. J., & Globetti, S. (2002). Political trust and racial policy preferences. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 253–276.

Hibbing, J. R. (2002). The people’s craving for unselfish government. In B. Norrander, & C. Wilcox (Eds.), Understanding public opinion (Chap. 14). Washington, DC: C.Q. Press.

Keele, L. (2005). The authorities really do matter: Party control and trust in government. Journal of Politics, 67, 873–886.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analysis: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 347–361.

Levi, M., & Stoker, L. (2000). Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 475–507.

Miller, A. H. (1974a). Political issues and trust in government: 1964–1970. American Political Science Review, 68, 951–972.

Miller, A. H. (1974b). Rejoinder to comment by Jack Citrin: Political discontent or Ritualism. American Political Science Review, 68, 989–1001.

Miller, A. H., & Borrelli, S. (1991). Confidence in government during the 1980s. American Politics Quarterly, 19, 147–173.

Miller, A. H., Gurin, P., Gurin, G., & Malanchuk, O. (1981). Group consciousness and political participation. American Journal of Political Science, 25, 494–511.

Romer, D., Kenski, K., Waldman, P., Adasiewicz, C., & Jamieson, K. H. (2004). Capturing campaign dynamics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rosenstone, S. J., & Hansen, J. M. (1993). Mobilization, participation, and democracy in America. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Shingles, R. D. (1981). Black consciousness and political participation: The missing link. American Political Science Review, 75, 76–91.

USCCR (2001). Voting irregularities in Florida during the 2000 presidential election, executive summary. Retrieved from http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/vote2000/report/exesum.htm.

Verba, S., & Nie, N. H. (1972). Participation in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Walsh, K. C. (2004). Talking about politics: Informal groups and social identify in American life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weatherford, M. S. (1987). How does government performance influence political support? Political Behavior, 9, 5–28.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The author would like to thank Jeff Fine, Scott McClurg, three anonymous reviewers, and the editors for helpful comments on earlier drafts. All remaining errors are the author’s alone.

Appendices

Appendix A: Question Wording and Summary Statisitcs

Political trust: “Thinking about the federal government in Washington, how much of the time do you think you can trust the federal government to do what is right? Just about always, most of the time, or only some of the time?” Mean: 0.43, SD: 0.20.

Clinton, Gore, and Bush Evaluations: “On a scale of 0 to 100, how would you rate _____? Zero means very unfavorable, and 100 means very favorable.” Fifty means you do not feel favorable or unfavorable.” Clinton: mean: 0.50, SD: 0.35. Gore: mean: 0.52, SD: 0.32. Bush: mean: 0.52, SD: 0.28.

Economic evaluations: “How would you rate economic conditions in this country today? Would you say they are excellent, good, only fair or poor?” Mean: 0.59, SD: 0.27.

Policy satisfaction: Spending Preferences: “Should the federal government spend more money on this, the same as now, less or no money at all?” (1) social security, (2) schools, (3) health care, (4) Medicare, (5) Medicaid, (6) missile defense, (7) defense, (8) welfare. Problems: “Is _____ an extremely serious problem, serious, not too serious or not a problem at all?” (1) tax rates, (2) lack of health insurance, (3) under-punishment of criminals, (4) immigration, (5) poverty, (6) job loss to foreign competition. Each question is scaled from 0 to 1 then summed to form one variable and rescaled again to range from 0 to 1. High values indicate greater satisfaction. Mean: 0.43, SD: 0.24. The various policy items are weighted equally and included in an additive index of policy satisfaction where high values are associated with greater policy satisfaction.

Party identification: “Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, or something else?” Democrat: 45%; Republican: 41%; Independent: 14%.

Appendix B: Racial Differences in Predictors of Political Trust

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Avery, J.M. Race, Partisanship, and Political Trust Following Bush versus Gore (2000). Polit Behav 29, 327–342 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-006-9021-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-006-9021-6