Abstract

Many believe that there is at least some asymmetry between the extent to which moral and non-moral ignorance excuse. I argue that the exculpatory force of moral ignorance—or lack thereof—poses a thus far overlooked challenge to moral realism. I show, firstly, that if there were any mind-independent moral truths, we would not expect there to be an asymmetry in exculpatory force between moral and ordinary ignorance at all. I then consider several attempts the realist might make to deny or accommodate this datum, and show why none of them work.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The black American standup comedian Dave Chappelle tells the following story: Dave is driving around a nightly New York City with his white friend Chip. Chip is in the driver’s seat but has been drinking; at a traffic light, he capriciously decides that he needs to “race” the car next to him. Unsurprisingly, Chip and Dave get pulled over by the police for speeding. Dave is high on weed, and scared to death. Chip, on the other hand—not so much: “Dave, just relax … Let me do the talking”, he says. The cop approaches the car, and informs drunk Chip about his illicit speeding. Dave is amazed and bewildered by Chip’s response, which he describes as follows:

You wanna know what he said? This was almost exactly what he said. I couldn’t believe it. He says:”Oh, oh. Sorry officer. I… I didn’t know I couldn’t do that.” I was fucking shocked! The cop said, “Well now you know! Just get outta here.

And with that, Dave and Chip are let off the hook. This exchange is funny—and I apologize for explaining part of the joke—for the way it illustrates the privileged position Chip enjoys vis-à-vis the police. It’s not just that he isn’t scared of the police (he even refuses to turn down the radio before talking to the officer); rather, while the police tends to crack down on black people with the full force of the law and, all too often, more than that, Chip is perceived as so unthreatening that he is, in an important sense, above the law—ignorance of which, as everyone knows, does not excuse.

I share Dave’s bewilderment, and want to see what follows from it. Recently, the phenomenon of normative ignorance has received increasing philosophical attention. In particular, the focus of the debate has been on the exculpatory force of moral ignorance—the degree to which moral ignorance does or does not affect transgressors’ blameworthiness, and whether it can mitigate or even eliminate moral responsibility.Footnote 1 Some argue that moral ignorance can exculpate. Some argue that it cannot.Footnote 2 One important aspect that, to my best knowledge at least, has been completely overlooked so far is what the exculpatory force of moral ignorance—or lack thereof—would imply for metaethical questions. Boldly put, I will argue that if moral ignorance does not have exculpatory force, then moral realism is false. At the very least, I wish to argue that the comparative exculpatory power of moral ignorance poses a puzzle for the realist, and to show how intricate and formidable this puzzle is.

There are five sections. In the first, I will explain the asymmetry in exculpatory force between ordinary and moral ignorance. In the second, I will argue for the conditional claim that the asymmetry, if there is one, poses a challenge to the moral realist. There are three main ways for the realist to respond to the challenge: deny that the asymmetry exists, explain why it does, or show it to be metaethically irrelevant. In the third section, I will consider whether the existence of the asymmetry can be denied in realism-friendly ways, and argue that attempts to do so face serious obstacles. In the fourth, I show that attempts at explaining, in realism-friendly ways, why the asymmetry exists, granted that it does, are problematic, too. In the fifth and final section, I consider whether the realist can show that the asymmetry in exculpatory force is actually metaethically irrelevant, because differences in blameworthiness reflect differences in quality of will, and argue that the prospects of this strategy are limited as well.

2 The asymmetry

Consider the following two principles:

-

(1)

If subject S performs a morally bad action A on the basis of a false non-moral belief that p and she is not blameworthy for holding p, then S is not blameworthy for performing A.

-

(2)

If subject S performs a morally bad action A on the basis of a false moral belief that q, and even if she is not blameworthy for holding q, then S can be at least somewhat blameworthy for performing A.

Call the conjunction of (1) and (2) the asymmetry. I do not wish to get hung up on technical details at this point. The gist of the asymmetry is that non-culpable ordinary ignorance will typically excuse, whereas non-culpable moral ignorance typically will not. This datum is more than enough for my argument to get off the ground.

A frequently used pair of examples illustrates the asymmetry. If a father gives his children something to drink that contains poison, but he does not believe that it contains poison (and hence does not know that it contains poison) and he cannot be blamed for not believing that it contains poison, then he is not blameworthy for unwittingly poisoning his children. It may be a tragedy, but not a case of morally wrong action. If a father gives his children something to drink which he knows, or indeed merely believes, to contain poison, but non-culpably believes that poisoning his children is not wrong, then he is blameworthy for poisoning his children—at the very least, we hesitate to exonerate him as thoroughly as in the first case. In what follows, I will use this asymmetry to develop my challenge to moral realism.

Let me emphasize already at this point that some may not share the above intuition. However, my argument is supposed to work whether or not one does, because it hinges primarily on the conditional claim that if there is an asymmetry in exculpatory power, then moral realists have a problem. Moral realists who do not believe that there is such an asymmetry are of the hook for now, although I will argue below that they, too, face serious obstacles when it comes to explaining, in realism-friendly terms, why there is no asymmetry.

It is surprisingly difficult to make the above two cases perfectly parallel. Consider the fact that in describing the first case in which the father mistakenly believes the substance to be drinkable, we are tacitly given at least a somewhat clear idea of how the father’s error may have come about. Some villain may have replaced the drink with poison, for instance, or maybe two jars were wrongly labeled. In describing the second case, we are given no such idea. In fact, it seems rather difficult to understand how such a mistake could have occurred at all. If we are supposed to believe that this father is otherwise sane, his error becomes downright unintelligible, and indeed mysterious.

It is an interesting fact in its own right that it is so difficult to describe a case of mundane non-culpable moral ignorance that closely parallels cases of mundane non-moral ignorance. For why, if moral realism is true, would that be so? If there are mind-independent moral facts, it should be perfectly possible to come up with a suitable example to illustrate (2). And if it is not, it seems fair for the anti-realist to demand an explanation for this fact.

To be sure, our intuitions can also be swayed in the opposite direction. Rosen (2003, 64ff) makes a great deal out of a case involving an ancient Hittite slave owner to whom it never occurs that his buying, selling and exploiting human beings could be morally objectionable; Martha Nussbaum wrote about Bernard Williams that he was “as close to being a feminist as a powerful man of his generation could be”;Footnote 3 standards of blame shift, in particular across generations and with regard to those who are trapped in now obsolete worldviews and practices. All of this seems to cast the asymmetry into doubt.

Note, however, that the asymmetry does not state that an agent who acts on the basis of non-culpable moral ignorance is necessarily blameworthy for her action. She merely can be, whereas in cases of non-culpable non-moral ignorance, this possibility seems to be all but ruled out. This modally weak contrast is sufficient for my purposes, since what matters for there to be an asymmetry is that there be at least some difference, however subtle or small, in the degree to which non-culpable moral and non-moral ignorance affects agents’ blameworthiness.

Conversely, I do not wish to suggest that moral ignorance has zero effect on blameworthiness. My argument merely requires that in comparable cases—that is, ignorance of relatively mundane facts about the immediate environment or ignorance of rather obvious moral truths—the asymmetry stands. Likewise, I am not committed to the claim that non-moral ignorance always exculpates. I merely wish to suggest that there is some asymmetry here, and that realism is ill-equipped to explain it.Footnote 4

In setting up the asymmetry in this way, I do not want to beg the question against those who argue that (blameless) moral ignorance can exculpate just as much as (blameless) non-moral ignorance can (Rosen 2003 refers to this as the parity-thesis), and who thereby deny that there is an asymmetry in the first place. In the immediately following Sect. 3, the main aim of my argument is a conditional one: I do not intend to vindicate the asymmetry as such; instead, I wish to investigate how an asymmetry in the exculpatory power of various forms of ignorance, if there were one, would affect the plausibility of realist accounts in metaethics. I then go on to consider both options—that there is no asymmetry of the kind described above (3), and that there is one (4). Here, my argument takes the form of a dilemma: if there is an asymmetry between the way non-moral and moral ignorance exculpate, then this fact is puzzling for moral realists. The basic idea behind the second horn of my argument is this: if moral realism were true, then we would not expect such an asymmetry to exist at all. Therefore, the burden of proof of explaining why there is an asymmetry falls on the realist’s side, and the main attempts to explain it in realism-friendly ways do not work well. The best—most natural and intuitive—explanations for why there is an asymmetry are more compatible with anti-realist accounts in metaethics than they are with realist accounts.

On the first horn, the realist can deny that there is such an asymmetry. But rejecting that there is an asymmetry between the way non-moral and moral ignorance affect blameworthiness challenges moral realism as well, for the main attempts to come up with cases in which moral ignorance does excuse do not work well under realist assumptions, either. Here, too, the most natural and intuitive explanations for the putative exculpatory force of moral ignorance are more compatible with an anti-realist metaethics.

Finally, I consider the claim that the asymmetry is actually metaethhically irrelevant. If, as many authors argue, differences in blameworthiness track differences in subjects’ quality of will rather than some kind of epistemic failing (Mason 2015), then the fact that factual ignorance excuses while moral ignorance does not need not have any implications for moral realism whatsoever.

For what it’s worth, I happen to think that the asymmetry is not just rather strong and robust, but also extremely compelling. Let me emphasize again, however, that this doesn’t undermine either my conditional point, which is about the compatibility of realism and the asymmetry as such, or the rest of my argument, where I show that denying and rejecting the asymmetry both spell trouble for realism.

3 Does the asymmetry challenge moral realism?

Moral realism is the view that there are knowable, mind-independent moral facts.Footnote 5 This view has two components: an epistemological one, usually referred to as cognitivism, according to which we can form (justified) beliefs about the moral facts, and a metaphysical one, according to which at least some of these beliefs are mind-independently true.

The puzzle I wish to develop is epistemological rather than straightforwardly metaphysical. In this regard, it can be compared to the argument from disagreement or anti-realist challenges which are based on the putative non-existence of legitimate moral deference. I will point out that realist explanations of the asymmetry rely on a moral epistemology which is not the realist’s first choice—the asymmetry is much more plausible on an account that views morality as mind-dependent. The realist can thus accommodate a large part of my argument by changing her preferred epistemology but leaving her ontology untouched, saying that our attitudinal responses are simply the way in which subjects gain access to the response-independent moral facts.

This is a possible view (Kahane 2013), and it escapes many of the issues raised below. But it is also an unusual minority view, and the more natural combination is to pair cognitivism about moral judgments with response-independence about moral properties.Footnote 6 This is the account I will focus on: when I talk about realism, I shall refer to the conjunction of cognitivism about moral epistemology and mind-independence about the ontology of moral properties (see Clarke-Doane 2012 and Das 2016 for two recent examples of the same use; for earlier uses, see Smith 1991). This view, and this view alone, is the one I am challenging, although it should cover virtually all realist positions actually occupied by anyone.Footnote 7

Do those who endorse realism’s metaphysical claim have any actual reason to incur the aforementioned epistemological commitments at all, thus making them vulnerable to my challenge to begin with? I think the answer is “yes”. First of all, most moral realists want to accept a view in moral epistemology according to which moral knowledge is acquired through respectable, non-obscure means. I take this to encompass a very broad range of possible views, on which moral knowledge can be acquired, for instance, in fairly ordinary ways via perception, inference, memory, testimony, or even moral intuition (Audi 2004; Huemer 2005; Enoch 2011). Details and intrafamilial disputes do not matter for my purposes; what matters is that, for most moral realists, the source of moral knowledge is not supposed to be downright myterious, such as a benevolent demon seductively whispering moral truths into the ears of a chosen few.

Moral realists thus tend to be cognitivists about moral knowledge. And this is not a mere accident, since cognitivism is indeed the most attractive view for moral realists to adopt. I already pointed out that those who subscribe to the mind-independence of moral properties do not have to be cognitivists; but the alternatives seem rather less useful, since the view that, for instance, we gain access to moral properties via emotional responses, though possible, invites charges of moral skepticism (Sinnott-Armstrong 2006). This would not be much of a problem unless realists typically wished to avoid moral skepticism, for it leaves them essentially empty-handed: I take it that the prime (though perhaps not the only) motivation for being a moral realist is that this will facilitate our taking morality seriously (Enoch 2011) and acknowledge its binding authority, rather than having to succumb to its awkward and uncomfortable rules only half-heartedly or not at all. If there is no way of gaining reliable knowledge of what morality demands, however, we are in essentially the same position as if an error theory were true: either way, the moral facts can play no serious role in our deliberations and actions—in the latter instance, because there are none, in the former, because we cannot know what they are. Realism sine cognitivism is therefore rather less attractive than realism cum, and the two share a close elective affinity.

Why does the fact that non-culpable moral ignorance does not have the same exculpatory force as non-culpable non-moral ignorance challenge realism? The short answer is that if moral facts are plain, mind-independent facts about rightness and wrongness, it is hard to see why being ignorant of them should not exculpate. If there are moral facts, and we can know what they are, then we can also fail to know them: we can overlook, misconstrue, and dismiss them. Why should failures of this kind give rise to anything like the aforementioned asymmetry? On the face of it, I see no reason why it should. It may be, of course, that moral facts are especially easy for us to know, which may explain the asymmetry. I will discuss this suggestion at great length below (Sect. 5), and argue that it is unhelpful to the realist.

Notice that according to the realist, the moral domain and the facts inhabiting it are exactly the kind of thing we should expect to play the same role in our moral discourse and our attributions of praise and blame as the non-moral domain and the electric bunch of facts we find in it. It is characteristic of mind-independent facts that we can have a perspective on them: we don’t see the squirrel because we are on one side of the tree, and it is on the other. If moral facts are objective in at least this perspective-allowing sense, it seems unreasonable not to excuse people who act on while being ignorant of them.

My argument is not committed to the claim that realism is the only position that is challenged by the asymmetry. On the other hand, one may argue that the asymmetry is more easily accommodated by non-realist accounts in metaethics. The reason why moral ignorance does not have comparable exculpatory force may be that there are no moral facts for us to overlook, misconstrue, or dismiss. Consider the following quote: “Someone who claimed that it would be impossible to figure out what is obligatory by just thinking about the circumstances of action would be misusing the word “obligatory”. [This] is because we can subject our desires about what is to be done in various circumstances to critical evaluation by just reflecting on our desires that moral knowledge seems to be such a relatively a priori matter” (Smith 2000).Footnote 8 If gaining moral knowledge works (roughly) this way, we can readily see why moral ignorance should not affect attributions of blame in ways similar to ignorance of the non-moral kind. Acquiring moral knowledge is not about gathering information about mind-independent truths. It consists in consulting our own attitudes towards non-moral truths. For my argument to work, I thus do not need to hold that the challenge is specific to realism, and does not apply to other metaethical accounts as well. I suspect that it is indeed specific to realism, although I will merely sketch some reasons why this may be so in what follows. My suggestion will be that non-realist accounts of value (e.g. response-dependence accounts) are better equipped to explain the asymmetry than realist accounts are. Let me emphasize again, however, that my challenge to moral realism still works even if my suggestion should turn out to be incorrect. In that case, my argument would change its target and become a more generally skeptical one, but it would not become unsound.

One may wonder whether the challenge put forward here applies only to some versions of moral realism. I suspect that it does not, and that my point holds regardless of whether one thinks that moral facts are identical to natural facts (Boyd 1988; Brink 1989; Sturgeon 1988), that they merely supervene on them (Mackie 1977; Joyce 2002), or that they are irreducibly normative and sui generis (Huemer 2005; Enoch 2011). If the moral facts are mind-independent in the relevant sense, then why should being ignorant of them not exculpate just like being ignorant about other mind-independent facts does? If the moral facts are out there, it should be possible to miss them more or less easily, to maneuver one’s moral beliefs around them, as it were, in an epistemically infelicitous way. With regard to this issue, the particular ontology of mind-independent moral properties is neither here nor there.

Doesn’t the phenomenon of moral ignorance commit us to moral realism, rather than being incompatible with it? After all, if moral realism is false, and there are no moral facts, what is there for people to be ignorant about? This is a legitimate question. The short answer is that properties need not be mind-independent to allow for the possibility of us being wrong about them. They could, for instance, be constituted by our epistemically improved desires (Smith 1994), or by the constitutive requirements of agency (Korsgaard 1996; Velleman 2009; Rosati 2003; cf. Enoch 2006; Tiffany 2012). I will not defend this claim, but will simply assume that there is room for error and ignorance even for non-realists.

To be sure, there are some cases in which factual ignorance does not excuse, and seeing why these types of ignorance do not have the same exculpatory power as ordinary ones is very enlightening for my argument. Consider the following example: I stand with my stiletto heels on your foot, but I (non-culpably) don’t believe that I do. In this case, blame would be inappropriate. Compare: I know that I stand with my stiletto heels on your foot, but I don’t believe that this is painful. In this case the question of blame is very different, and in the latter case, it seems rather more unclear whether this type of ignorance excuses at all. The reason for this is very telling, and I will return to it below: in the “I didn’t know that it was painful” case, we simply find it too hard to believe that when someone knows pretty much all there is to know, factually, about a situation, she could not know this. But why should it be so implausible not to know that it is painful (or, by analogy, that causing pain is pro tanto wrong?) to stand on someone’s foot (or, by analogy, that causing pain is pro tanto wrong?)? This is because it is extremely easy to find out that stepping on a person’s foot is painful. In order to do so, we do not need to learn another fact about the situation; all we need to do is imagine how we would feel under similar circumstances, and voilà.

A similar point applies to lack of relevant belief, as in cases of negligence: I omit to put a warning sign next to an open hole in the floor in my shop. You fall in.Footnote 9 (It is dark in my shop and I am poor at maintenance. Deal with it.) If I was unaware that there was such a hole, I may be excused. If I claim to have been unaware of the possibility that people might fall in, I am blameworthy. In these two cases—neglicence and the rather elementary knowledge that standing on someone’s foot is painful—we are reluctant to assign blame, I wish to suggest, essentially out of incredulity. We find it hard to believe that someone could not know these things and therefore, we dismiss the claim to be excused as unwarranted.

Now the crucial thing to ask is why, in the case of moral ignorance, we experience the same kind of incredulity. My suggestion is that this intuition, too, tracks degrees of difficultyFootnote 10: we see no obvious way in which someone who is fully informed about the non-moral facts could then fail to know the moral facts as well—and this is because moral realism is false, and there are no additional, irreducibly normative moral facts to know on top of the ordinary facts; it is much more plausible that there are only non-moral facts plus our responses to them. Or so I will argue.

My challenge can be put forward somewhat more neatly with the following argument:

The Asymmetry Argument

-

(1)

Being non-culpably ignorant of the mind-independent moral facts does not have exculpatory power comparable to being ignorant of non-moral facts.

-

(2)

If there are mind-independent moral facts, then being non-culpably ignorant of them should have exculpatory power comparable to being non-culpably ignorant of non-moral facts.

-

(3)

(Part of) The best explanation of (1) in light of (2) is that there are no mind-independent moral facts.

-

(4)

Therefore, there are no mind-independent moral facts.

The remaining sections are organized around this structure. In the third, I will discuss possible realist rejoinders to premise (2). The fourth section will be about rejections of premise (1). I will also have something to say about (3) at various points. Inferences to the best explanation are comparative in nature: they crucially depend on the idea that a hypothesis—here: moral realism—fares worse with respect to the explanandum than an alternative—here: non-realist metaethical accounts. It is therefore important to at least sketch what such a superior alternative explanation might look like, and what makes it superior. Let me emphasize that I will not explain this in great detail. For now, I focus on showing that moral realism has a hard time explaining the asymmetry. The fifth section is about why this argument may have no bearing on metaethical issues at all. I conclude with some general remarks about the prospects of my argument and the family of new challenges to moral realism to which my argument contributes.

A lot hangs on the meaning of “comparably”, of course. Here is one possible understanding: we should have roughly the same exculpatory response to cases featuring comparable forms and degrees of ignorance: to the father who unwittingly poisons his children because he thinks the liquid at hand is water as to the father who poisons his children because he thinks poisoning them is a good thing. Likewise, we should have roughly the same response to the person who, through no fault of her own, subscribes to a deeply mistaken scientific world-view with objectionable moral consequences and the agent who non-culpably subscribes to a deeply mistaken moral framework. But we obviously do not have roughly the same response to these two types of comparable cases (which is compatible with the admission that in some incomparable cases, we do.) This off-the-cuff response may be untutored and best abandoned. For now, however, I will take it as my starting point.

In general, it should be noted that there are various ways for a subject to be ignorant of some (non-moral or moral) fact. Peels (2014); see also Le Morvan and Peels (2016) and Nottelmann (2016) distinguishes ignorance on the basis of false belief from ignorance due to lack of belief, suspended judgment or unwarranted belief. It is an interesting question whether the asymmetry holds for all these types of non-moral and moral ignorance: it may turn out, for instance, that there is no asymmetry in exculpatory power between suspended beliefs about some normative or non-normative fact, respectively. My discussion in this paper is restricted to cases of ignorance as false belief. I argue that an asymmetry in the exculpatory force between false moral and false-non-moral beliefs poses a challenge to moral realism. This point involves no commitment to whether a similar asymmetry applies to other ways of being ignorant.Footnote 11 However, the asymmetry I zoom in on is sufficient for my purposes.

Some have taken a more radical approach according to which there is no asymmetry not because both moral and non-moral ignorance occassionally excuse, but because both almost always do. Zimmerman (2008, 173ff, 2017) has argued for what he refers to as the “origination thesis”, according to which an action can only be morally culpable if it can be traced back to an action for which the agent is (directly) culpable and which she believed, at the time of acting, to be morally wrong. This has the surprising implication that both non-moral and moral ignorance can, in principle, excuse, and that the conditions required for this almost always obtain. Culpability for ignorant behavior is thus, according to Zimmerman, and in drastic contrast to our (possibly mistaken) everyday practices of praising and blaming, an extremely rare bird. There is no space here to respond in the required detail to the substance of Zimmerman’s intricate argument, so let it suffice to say that my argument is compatible with the revisionary claim that ignorant behavior is almost never culpable as long as in the few remaining cases where it is, there remains some asymmetry in the exculpatory force of non-moral and moral ignorance.

Let me remind you that I am not claiming that the asymmetry is perfectly incompatible with moral realism. Instead, I shall argue that moral realism offers the comparatively worse explanation of it. The asymmetry is pro-tanto evidence against realism, rather than strictly inconsistent with it.Footnote 12 My argument should thus not be seen as attempting a knock-down refutation of realism, but as a puzzle realists are particularly ill-equipped to resolve.

4 Is there an asymmetry at all?

Perhaps the best evidence for the fact that there is at least some asymmetry in the respective exculpatory power of moral and non-moral ignorance is that there are plenty of articles defending that moral ignorance can play an excusing role, while the exculpatory power of non-moral ignorance is always taken for granted. It would be hard to deny this very suggestive datum. The second best piece of evidence, at least for the intuitiveness of the asymmetry, comes from developmental psychology: children as young as 5–6 years use false ordinary beliefs to exculpate, but not false moral ones (Chandler et al. 2000; see also Mikhail 2007). Now the realist has two options: deny, contrary to this data, that the asymmetry exists, or explain why it does. I will take up these options in turn, starting, perhaps unsurprisingly, with the first.

Children Children are excused on the basis of moral ignorance. Take Eliza. Eliza is a 3-year old who loves going to day care. However, she also has quite a temper, and her more tenderly disposed playmates often have difficulties to cope with her outbursts. When she loses at a game, or when someone claims a toy she takes to be firmly entitled to, she snaps, and she has often been told off by her caregivers for hitting, biting or pushing her fellow would-be persons. It seems clear that we do not hold Eliza fully accountable; her educators will, of course, attempt to reign her in when possible. They may also inform her that she is not supposed to behave this way, and ask her to make amends and apologize. But we excuse her on the basis of her young age, and place all our blame on her parents or no one at all.

Does this example show that the asymmetry must be rejected? I doubt that it does. Firstly, one could question whether the fact that children are excused is due to their moral ignorance at all or merely due to factual ignorance. Is there any case in which we are inclined to excuse children that are clear cases of genuine moral ignorance, rather than them not really understanding the situation properly, or not really seeing the consequences of their actions?

But let us grant the point. Secondly, then, one could argue that even if one thinks that children are sometimes excused on the basis of genuine moral ignorance, the explanation for why this is the case does not support moral realism, that is, its cognitivist conjunct. Typically, the reason for our inclination to cut children some slack will be that their emotional capacities are not yet fully developed. They are simply unable to properly imagine how their actions may affect others and hurt their feelings.

A non-realist account of moral properties in terms of response-dependence explains this datum better than a realist one: Eliza is excused not because she is unable to appreciate facts about the rightness or wrongness of her actions, but because her emotional sensitivity has not yet developed enough for her to be disposed against inflicting unnecessary harm on others, and she does not yet have the requisite degree of self-control to step back from her vengeful desires and wait for them to cool off. In short: nothing about the reasons why children are excused due to their moral ignorance, and about how adults try to deal with this situation, suggests that cognitive access to mind-independent moral facts plays a crucial role.

Mental disorders Many mental impairments—from mental retardation (Anderson 1998) to modular deficiencies (from fairly specific ones like facial recognition/prosopagnosia to theory of mind/autism) to various delusions such as Capgras syndrome (Hirstein 2005) or neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or frontotemporal dementia—figure in excuses or exemptions of behavior otherwise deemed blameworthy.

Similar worries apply, however. Firstly, one could doubt that one can unambiguously identify a case in which we excuse mentally disabled people on the basis of genuine moral ignorance. People who suffer from paranoid schizophrenia or depression may well be in the grip of inaccurate (or perhaps, in the case of depression, unhealthily accurate, see Alloy and Abramson 1979) non-moral beliefs about the world or other people which may lead to various forms of undesirable behavior. Mentally disabled people such as individuals on the Autism spectrum are not known to fail moral/conventional tasks (Blair 1996). Their moral knowledge thus seems mostly intact.

Realists may want to reply that all it takes to recognize moral facts are the usual epistemic powers that figure in the acquisition of other forms of knowledge as well—so that when those powers are compromised, so is the capacity to gain moral knowledge. However, the impairments observed in people with mental disorders are typically too specific for it to be plausible that damage to subjects’ general purpose epistemic machinery may then have collaterally damaged their moral knowledge as well. Persons suffering from delusions (Bortolotti 2009) make highly specific cognitive errors: they are convinced their spouse has been replaced by an impostor, or claim not to be paralyzed when they evidently are. These impairments typically do not generalize to other types of knowledge or cognitive skills.

Conversely, even if one could attribute genuine moral ignorance to mentally disabled persons, and where the causes of their ignorance can be attributed to impairments of sufficiently general information processing mechanisms for this reply to work, the reason why mentally handicapped individuals are ignorant of such truths seems, as in the case of children, to have more to do with their ability to respond emotionally in appropriate ways, rather than with their inability to recognize the mind-independently existing moral facts. Autists, for instance, suffer from empathy deficits (Baron-Cohen 2009), as do patients with FTD (Mendez et al. 2005). In short: when the ability to recognize mind-independent facts is impaired as a result of a mental disorder, this ability will typically be too specific to supply an explanation of the asymmetry that will help the moral realist; and when the impaired ability is sufficiently general, it tends not to affect abilities that are concerned with the recognition of facts at all, but about patients’ emotional sensibilities and how they are compromised.

Psychopaths In many ways, psychopaths are the realist’s best shot. They seem to exhibit glaring moral ignorance, as evidenced by the fact that they are unable to draw the moral/conventional distinction (Blair 1995; Nichols 2004); their general sanity and intelligence are uncompromised by their disorder, so they remain appreciative of mind-independent facts; and yet, it is often argued that they ought to be exempt from blame (Levy 2007; cf. Maibom 2008).

Again, it is worth asking whether psychopaths are genuinely morally ignorant. Here, denying that they are appears much more promising, as many of the judgmental and behavioral patterns found in psychopathic patients and offenders are more plausibly explained by motivational than by cognitive deficiencies. Psychopaths (and acquired sociopaths) know right from wrong, but do not care (Cima et al. 2010; Roskies 2003).

Moreover, recent evidence suggests that the findings originally supporting psychopathic moral ignorance may have to be reconsidered (Levy 2014). In Blair’s famous study on psychopathic inmates’ ability to distinguish moral from conventional violations, it was found that they cannot, albeit in surprising ways: participants turned out to treat all norms as moral, contrary to the more nearby expectation that they would treat all norms as conventional. This pattern was explained by psychopathic inability to draw the relevant distinction, combined with their desire to appear reformed and ready for society, which made them overshoot the mark. In a recent forced choice paradigm, however, this incentive was removed by telling participants upfront how many of the items given to them belonged in each category, which restored their task performance to normal levels (Dolan and Fullam 2010; Aharoni et al. 2012). It thus appears that according to the most frequently used criterion, psychopaths do have moral knowledge, which rather undermines their usefulness for the moral realist for rejecting the asymmetry.

But even if one grants that psychopaths are genuinely morally ignorant, their ignorance primarily seems to be due to their emotional impairments of reduced empathy and guilt—in fact, these are part of the diagnostic criteria established by the PCL-R—in cases that concern the suffering of others (they do not realize that it is wrong to hurt others, for example). Their moral understanding of situations involving violations of norms of fairness is perfectly normal (Koenigs et al. 2010), at least when their own standing has been affected by such violations. This schism in the kinds of moral knowledge they are capable of maps exactly onto their respective impaired and normally functioning affective capacities: their capacity for empathy is impaired, but their capacity for anger and outrage is not. Presumably, their selective moral ignorance is thus due to impaired emotional responses, not due to an inability to recognize mind-independent moral facts.

In all cases mentioned thus far, it is unlikely that deficient behavior is based on genuine, non-derivative moral ignorance in the first place. But the important thing to file away is that even if one grants that it is, the explanation for where this ignorance comes from features emotional impairments and poor factual knowledge first and foremost, rather than an inability to appreciate mind-independent moral facts.

Let me emphasize again that I am not committed to the claim that moral ignorance never exculpates, so the fact that there are some cases in which it does exculpate does not undermine the idea that there is some asymmetry. But the fact that the alleged counterexamples are all based on special cases should not only make us suspicious; it also shows that apparently, the asymmetry does apply to normally functioning, healthy adults. The explanation this demands is more than enough for my argument.Footnote 13

In order to escape the challenge by rejecting premise (2) of the asymmetry argument, the realist would thus have to show, on a priori grounds, that the asymmetry couldn’t hold. In my view, this claim carries with it an exceptionally heavy justificatory burden, so I will only hint at what type of argument may yield this conclusion, and briefly sketch what I think is wrong with it.

Moral luck In one way or another, the main attempts when it comes to rejecting the asymmetry all draw on the phenomenon of moral luck.Footnote 14 Arguments from moral luck hold that in many cases, one’s moral ignorance will be due to causal factors which are beyond one’s control, such as which moral community one is born into—for instance, a community of slave-owners in the antebellum south whose objectionable views one ends up adopting. But, the argument continues, one cannot be blameworthy for one’s bad luck. However, as has often been noted, as plausible as the control principle seems to be when considered in the abstract, this initial compellingness tends to fall apart in light of specific cases, especially ones involving circumstantial luck. Two agents may have identical dispositions but find themselves in benign or malignate circumstances (e.g. in Nazi Germany with all its social pressures or outside of it) which leads only one of them to commit horrible crimes or remain complacent when confronted with such crimes. She would not have behaved this way if placed in different circumstances; conversely, the luckier agent would have behaved the same under comparably detrimental conditions. Nevertheless, the two agents are differentially blameworthy.Footnote 15

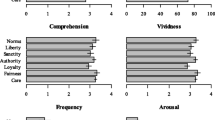

In saying this, I rely on my intuitions about cases of circumstantial moral luck. Not everyone shares those intuitions, of course. Susan Wolf’s famous work on normative insanity, for instance, draws on the exculpatory force of moral luck to arrive at the opposite conclusion. In order to adjudicate, we could employ empirical evidence. If experimental philosophy has taught us anything (and I think it has), then it is that our intuitions are a curious thing—we often do not know the causal origins of our intuitive beliefs, and consequently, we often do not know whether they are elicited by relevant or extraneous factors. Even more surprisingly, we often do not know which intuitions we have, or overestimate the degree to which they are shared. This fact is not just psychologically interesting. To the extent that philosophers appeal to shared intuitions, the force of such an appeal can be severely undermined, particularly in cases where an entire argument is based on little else but such putatively shared intellectual seemings. It is thus relevant and warranted, when such an appeal is made, to investigate empirically whether the invoked intuitions are as intuitive as they are alleged to be. In this spirit, Faraci and Shoemaker (2010) have shown that folk intuitions undermine Wolf’s counterexamples: non-culpable moral ignorance mitigates blame only somewhat, but nowhere near completely.

I have said in the beginning that there are some cases of extreme moral brainwashing, like JoJo’s, which make us inclined to think that the subjects described in those scenarios are excused from being responsible for their immoral acts by their deep and all-encompassing moral ignorance. Perhaps these are extreme cases real-life analogues of which are probably very hard to come by. Be that as it may, I wish to insist that these cases do not help the moral realist, because here, too, the explanation for why we allow moral ignorance to excuse in these cases does not support realism. JoJo seems to be the victim of extreme emotional manipulation, rather than cognitive biases, or an inability to appreciate facts. He has not been given false factual information; rather, his ability to properly respond to facts has been twisted and distorted. On the other hand, Wolf does intend JoJo to be genuinely morally ignorant, although the way she describes it, JoJo’s case of bad moral luck is highly exceptional.

One final thing to consider: Faraci and Shoemaker (2014, 16) have shown that, intuitively, moral ignorance does not just leave blameworthiness more or less unaffected; in some cases, it actually increases praiseworthiness. People judge a man who acts against the racist beliefs he was brought up with and still holds by helping a black man in distress as more praiseworthy than a comparable case.Footnote 16 This is a striking pattern which, I would suggest, makes no sense whatsoever from a realist perspective. On a realist account, the proper exercise of moral agency should be facilitated by knowledge of the moral facts. It would be mysterious, then, why ignorance of those facts should have such an amplifying effect on an agent’s praiseworthiness.

5 Can the asymmetry be explained away?

Let me turn now to an alternative realist strategy. Perhaps she can, rather than deny that there is one, satisfyingly explain the asymmetry in ways that fit with her realist commitments. I argue that there are two general ways to explain the puzzling contrast in the respective exculpatory powers of moral and non-moral ignorance and that neither supports realism: for one, pragmatic explanations aim to show that there are some extrinsic, perhaps consequentialist, reasons for our unwillingness to let moral ignorance count as a valid excuse. Epistemic explanations, for another, are based on the idea that our type of epistemic access to moral truths—the way we arrive at them—is such that the asymmetry should come as no surprise.

Pragmatic explanations The asymmetry could be pragmatic in nature. Very roughly put, the idea behind this is that it would not be prudent, or desirable, to disrespect the asymmetry in our everyday practices of assigning blame and praise. For instance, if the asymmetry did not hold, everyone would always have a watertight excuse for everything: one could always say that one did not know what was right or wrong, and it would be difficult for others to disprove this defense.

After all, how could one disprove it? What is the evidence one person could cite for believing that another person was in possession of a certain piece of moral information? In the case of non-moral information, this seems unproblematic: one could demonstrate that the person was present at the scene, looked in the right direction, had functioning vision, and that lighting conditions were normal. What type of evidence would I need to adduce to show that you were in a position to form a true moral judgment? Sure, you witnessed this group of youths pour gasoline over a cat and ignite it; you didn’t stop them, and now you are trying to defend yourself by saying that you didn’t know that feline treatment of this kind was objectionable. What is my reply? How could I show that you had to be able to see that this was wrong? In short: accepting excuses on the basis of non-moral ignorance would have disastrous social consequences in the form of a get-out-of-jail-free card for everyone. Given that there are good consequentialist reasons for having a functioning practice of holding people accountable, we must accept the asymmetry for such pragmatic, instrumental reasons.

Does this strategy help the moral realist explain the asymmetry in a satisfying way? On a first glance, it seems that it does. After all, if the asymmetry can be explained instrumentally, the claim that if there were any mind-independent moral facts, we would not expect the asymmetry to exist at all can be rejected, because said instrumental reasons would recommend our respecting the asymmetry regardless of whether or not there were any moral facts, simply because this would be a good and useful thing.

On a second glance, there are reasons for doubt. Firstly, pragmatic explanations of the asymmetry seem mostly relevant in legal contexts rather than the context of moral norms and values. The “mistake of law” doctrine, as it is typically called, is supposed to provide an incentive for citizens to familiarize themselves with the law. By not granting normative ignorance any exculpatory power, the state offloads its interest in the dissemination of legal knowledge onto the motivations of individual citizens. Since under modern, liberal conditions, the state has no comparable interest, nor indeed a coherent idea of, the dissemination of moral knowledge throughout the public, this particular rationale for not allowing non-moral ignorance to exculpate is removed.

Moreover, even if the realist could capitalize on parallels between the legal and the moral, pragmatic explanations of the asymmetry in the legal context have been challenged (Kahan 1997). Again, the idea behind these explanations is that the state has an interest in disseminating legal knowledge amongst its citizens; by providing them with an incentive to know the law (because being ignorant of it is no excuse), this result is guaranteed. Kahan, however, argues that the state does not actually have an unambiguous interest in securing that people know the law. When they have detailed knowledge of it, this will only result in the fact that people will be able to exploit the gap between valid moral norms and the legal norms that only ever embody them imperfectly. Detailed legal knowledge facilitates mere compliance with exactly what is required by the law and nothing more, whereas the state has an interest in incentivizing its citizens to be good people even when there is no law (yet) to specify what exactly this means. (Kahan 1997, 129ff). The state thus does not have a pragmatic interest in the asymmetry due to the fact that it wants people to behave in legally supererogatory—that is: moral—ways.

However, even if the pragmatic explanation did work for moral ignorance outside the legal context, this would not explain the asymmetry in a way that helps the moral realist. For why is it that if we allowed moral ignorance to excuse, people would always have a watertight excuse readily available to them? Why would it be so easy for people to claim moral ignorance, far easier than to claim ignorance of the non-moral facts in favorable epistemic conditions?

The explanation for this comes back to a point made earlier. Presumably, the reason why it would be so easy for people to claim lack of relevant moral knowledge is because in the case of non-moral ignorance, one could simply investigate which information was objectively available to the agent at the time of committing the act in question. (Was the agent present? Could she see what was going on?) Apparently, this option is simply not available to us in the moral case because these cases are not about which “moral information” was objectively available to the agent at the time at all—which is to say that the pragmatic difference we make here presupposes that there are no objective, mind-independent moral facts the agent could have been ignorant about in ways similar to non-moral ignorance.

Pragmatic explanations of the asymmetry that exploit parallels to the legal context thus backfire. Facts about what is lawful are evidently not a mind-independent part of a situation or an event. We can look at a situation, get all the facts right, and still have no idea what is legal or illegal in it. Positive legal norms are quite literally constructed. Because of this, ignorance of the law among legally untrained citizens is profound and pervasive. Because of the constructive nature of positive law, it would also be very difficult, if not impossible, to show that a particular subject could not have been ignorant of it. Therefore, claiming legal ignorance would always offer a plausible excuse. It is thus the falsity of realism about this domain of norms that makes pragmatic explanations of the asymmetry possible to begin with.

Epistemic explanations The important lesson we may take away from the discussion of pragmatic explanations of the asymmetry is that the difference in the exculpatory powers of moral and non-moral ignorance may track degrees of difficulty. The more difficult it is to obtain knowledge about a target domain, the more likely we are to think that ignorance about that domain has exculpatory power. It could thus be that there are moral facts, but that they are almost always so easy to know that it is almost never plausible to claim that one did not.Footnote 17

The idea that moral knowledge is in some sense readily available or easily attained has attracted a lot of support from an eclectic group of eminent people.Footnote 18 Michael Smith, for instance, writes: “It is agreed on nearly all sides that moral knowledge is relatively a priori, at least in the following sense: if you equip people with a full description of the circumstances in which someone acts, then they can figure out whether the person acted rightly or wrongly just by thinking about the case at hand” (2000, 203). Many others believe that moral knowledge is “easy” in just this way: “Morality does not require beliefs that are not known to all moral agents” (Gert 2004, 90). And: “this book […] contains no new information about what kinds of actions morality prohibits, requires, discourages, encourages, or allows. Anyone who is intelligent enough to read this book already has all of this information” (3). Here is Nicholas Rescher: “Anything that requires extensive knowledge or deep cogitation is ipso facto ruled out as a moral precept or principle. The very idea of moral expertise…is for this reason totally unrealistic” (2005, 200). Michael Smith again: “Our moral life seems to presuppose that [moral] facts are in principle available to all; that no one in particular is better placed to discover them than anyone else” (1994, 5). And, finally: “It seems implausible to say that it would take a ‘moral genius’ to see through the wrongness of chattel slavery” (Guerrero 2007, 71; see also Wieland 2015). So there is widespread, though perhaps not universal, agreement that obtaining moral knowledge is easy. Put this together with the claim that we are inclined to grant ignorance about a domain exculpatory power only if obtaining knowledge about the facts in the respective domain is at least somewhat difficult, and we have an epistemic explanation for why moral ignorance does not exculpate.

But again, the explanation for why it is so easy to gain moral knowledge does not fit well with realist accounts of moral value—on which, to put it simply, it should not be. “Easy” knowledge in the sense at issue here should only be expected in domains where knowledge is either trivial as far as its content is concerned (e.g. the basic truths of arithmetic or certain conceptual truths such as that all bachelors are unmarried men), or obvious as far as its availability, given our means of access to it, is concerned (e.g. knowing that one is in pain). However, it is implausible to think that, if moral realism is true, moral facts should be this easily accessible or trivial.

Availability and triviality Why should moral truths be so readily available to epistemic subjects? Presumably, this is because once we have a non-moral, descriptive understanding of a situation, we get a moral, normative understanding of the situation “for free”, without having to scrutinize the situation any further in pursuit of the elusive mind-independent moral facts. But this is precisely the opposite of what we would expect if moral realism were true. If there were any such facts, it is hard to see a reason why they should be so easily accessible. It seems more plausible to concede that once we have a more or less thorough grasp of the situation, the ease of access to what morality requires stems from the fact that we only need to consult our emotional reactions to the case at hand to find out about its moral status, rather than having to look for any irreducible moral facts over and above the non-moral facts.

The basic point of this argument is that if realism were true, it would be hard to see why knowledge of mind-independent evaluative facts should be as easily available as to adequately explain the contrast.

But perhaps there is another way. The easiness with which true moral beliefs are acquired may not be due to the fact of moral truths somehow throwing themselves at us, but due to the content of those truths. If, for instance, moral propositions are a priori, then many of them may well be trivially true (or false). This triviality response offers an explanation for why moral truths may be so easily accessible without undermining moral realism.

There are several problems with this. Firstly, one could argue that moral knowledge just isn’t a trivial matter. Suggesting that it is would be implausibly optimistic and explanatorily inadequate, as it would either predict much more rapid and smooth moral progress or render the very need for moral progress unintelligible in the first place. It would also be empirically unconvincing, as it would fail to account for both the widespread interpersonal moral disagreement as well as intrapersonal moral uncertainty found in the real world.

Moreover, it seems hard to understand how knowledge of mind-independent facts could be trivial at all. It may not be very difficult to determine the number of chairs in my office. But it is certainly far from trivial, or a priori, and one could describe various close possible worlds in which I may form false beliefs about what the correct number is. Knowledge of mind-independent facts requires informational input, the reception of which can go wrong. If knowledge of objective moral facts is different, realists must explain why.

Three further points put the nail in the coffin of the triviality reply. For one, the reply comes dangerously close to denying that moral ignorance can ever be non-culpable. This is unwelcome for several reasons. Firstly, this move seems to amount to the admission that, in fact, moral ignorance can never exculpate. If only non-culpable forms of ignorance have exculpatory force, and moral ignorance is so easily avoided as to always be culpable, moral ignorance can never stifle blame. Secondly, it suggests that moral knowledge is always so easily obtained that when one knows all the facts, one always ought to know what’s right. But ought implies can, so for this to make sense, it must always be possible for someone to know the moral facts when one knows the non-moral facts. But if moral facts are mind-independent and objective, how could this be? This throws us back to the availability strategy rejected above.

For another, the cases that opponents of the asymmetry most frequently invoke, such as the ancient Hittite slaveowner, tend to feature scenarios in which the circumstances for acquiring true moral beliefs are paradigmatically deleterious, thus rendering successful epistemic performance extremely difficult, if not downright impossible. This, too, makes the triviality strategy very difficult to sustain: it does not work for the very cases that motivated it in the first place.

Most importantly, perhaps, the triviality strategy is just not available for all, or even for most, brands of moral realism. Notably, Cornell realists maintain that moral truths are synthetic and thus cannot be known by reflecting on one’s conceptual intuitions alone (Boyd 1988; Brink 1989; Sturgeon 1988; cf. Tropman 2014). In fact, Cornell realists often maintain that moral knowledge is acquired observationally, which makes the asymmetry particularly hard to account for. Other, non-naturalistic forms of realism explicitly state that obtaining moral knowledge on the basis of reason or intuition is difficult (Huemer 2008; Enoch 2011), and that this is what explains the slow pace of moral progress. There are thus few versions of moral realism that could count any real people among its adherents for which the strategy would work.Footnote 19

6 Is the asymmetry metaethically irrelevant?

One final option for the realist is to argue that with respect to the existence of mind-independent moral facts, the asymmetry in exculpatory force is actually neither here nor there. What grounds differences in praise- and blameworthiness are differences in the quality of will agents display towards those affected by their actions (Mason 2015; Arpaly 2002, 2003; Markovits 2010). If one acts from ill will, whether or not one knows one’s action to be wrong is irrelevant to the issue of whether or not one is blameworthy. Hence, the issue of moral ignorance has nothing to do with the asymmetry at all.

Consider the fact that the two fathers who poison their children are importantly different in that only one of the two fathers intentionally poisons his children under that description.Footnote 20 Plausibly, this constitutes an objectionable quality of will, which explains why we blame this father but exonerate the other. What matters, it seems, is the quality of will my actions express towards others. If I torment a snail, non-culpably believing it to be non-sentient, I may be excused. If I do the same while being aware of the suffering I am causing, it seems that I am blameworthy for acting out of indifference or even cruelty.Footnote 21

Quality of will approaches are thus attractive for the moral realist because they seem to show that regarding the asymmetry, there is nothing for them to deny or explain. Note that in examining the prospects of this reply, I cannot do justice to the complexity of quality of will accounts, or discuss them in any detail. In what follows, I only wish to consider the extent to which quality of will accounts of praise and blame can be used to shield moral realism from the asymmetry challenge. Let me offer two replies to the suggestion just sketched.

The first is a moderate, but to my mind nevertheless interesting one about the resulting metaethical landscape. Suppose that the argument I have developed so far is sound. Realists can neither successfully deny the asymmetry nor explain it away. Suppose, also, that quality of will accounts would provide an explanation of the asymmetry that shows it to be metaethically irrelevant. This would mean, then, that the asymmetry gives realists strong reason to become quality of will theorists, because this is the most promising way for them to get rid of the challenge posed by the asymmetry. Now, many prominent quality of will theorists are already moral realists, because they insist that agents agents are blameworthy to the extent that they disregard the features that are in fact right- or wrong-making (see, for instance, Arpaly 2015). But (until now?) there is no special reason for moral realists to subscribe to a quality of will account of blameworthiness. At the very least, my argument would have the interesting result that realists should subscribe to such an account. In the end, then, one could hold that, though the asymmetry can be accounted for by moral realists, it creates intense pressure for them to adopt a quality of will approach. And this, it seems to me, would be a substantial and surprising discovery about the logical connection between two accounts previously thought to hang together more loosely.

A second possible reply is this. Suppose the result of my argument is that in order to escape the asymmetry, realists need to adopt a quality of will account of praise and blame. It could then be argued that the resulting combination of realism and the quality of will approach leads to the following problem that has to do with the particular shape of quality of will theory we get when such a theory is combined with standard moral realism.

Let me return to factual ignorance for a moment. Moral failings that occur due to factual ignorance are blameworthy if, and only if, the agent violated her procedural epistemic obligations in acquiring her false non-moral beliefs (or in remaining oblivious of some relevant non-moral fact). But for the moral realist, moral ignorance should consist in essentially the same kind of thing: a false belief, or lack of true belief, about some relevant mind-independent moral fact. This means that, for the realist, there are cases in which an agent’s moral ignorance is due to some violation of her procedural epistemic obligations regarding which objective moral facts there are. Now, the realist who wants to escape the challenge posed by the asymmetry may want to hold that although such cases do exist, blame and praise nevertheless only track an agent’s quality of will, rather than violations of epistemic duties regarding objective non-moral or moral facts. But why would this be the case? Why would only differences in quality of will, but not moral ignorance based on irresponsible epistemic behavior regarding the objective moral facts, the possibility of which realists should acknowledge in virtue of the internal logic of their position, have an impact on an agent’s blame- or praiseworthiness?

My point is that a version of the asymmetry, and the task of explaining it, comes back to haunt the moral realist who has adopted a quality of will account of moral praise and blame in order to escape the asymmetry. For now the realist has to explain why only differences in quality of will ground differences in praise and blame, while moral ignorance resulting from a violation of an agent’s procedural epistemic obligations does not, which is simply a restatement of the claim that moral ignorance has no exculpatory force. We may ask why, regardless of the significance of an agent’s quality of will to her blameworthiness, which may well be considerable, there is an asymmetry in exculpatory force between non-culpable factual and moral ignorance, such that the former is relevant to an agent’s blameworthiness, while the latter is not. We are thus thrown back to our original question. Realists could of course say, without further explanation, that non-culpable moral ignorance simply lacks exculpatory force. But this suggest that either, moral realism cannot be combined with quality of will theories in the desired way, or that the combination of realism and quality of will accounts can only escape the asymmetry by begging the question against it. At any rate, if moral realism is true, it would be surprising if non-culpable moral ignorance had no relevance whatsoever to issues of praise- and blameworthiness. So the challenge still stands.

I do not wish to suggest that quality of will realists, as one may call them, do not have the correct explanation of what grounds praise- and blameworthiness in even the majority of cases. My point is that the realist should have no problem admitting the existence of at least some cases in which an agent non-culpably overlooks some relevant moral fact. It then seems legitimate to ask why such cases should have no relevance at all for questions of praise and blame. And if they do after all, why should agents not be excused in such cases, if moral facts are indeed mind-independent?

This point can also be expressed as a dilemma. Remember that the quality of will realist wants to explain the asymmetry in a way that renders it metaethically irrelevant. Now the quality of will realist has the following two options: either, an agent’s quality of will depends on the moral reasons an agent merely believes to have, or it depends on the reasons the agent actually has. If the former is true, then the position cannot explain why the two fathers are different, because both believe to have good reasons for their actions (or, at least, do not believe that there are any good moral reasons against it). If the latter is true, and quality of will depends on the reasons that actually obtain, then the most natural explanation a realist could give for the fact that the morally ignorant father is blameworthy while the factually ignorant is not, and hence what exactly it is about the morally ignorant father’s will that makes it a fitting object of blame, is that the morally ignorant father hasn’t recognized the morally relevant facts. But why is the other merely factually ignorant father not also blameworthy, since he has failed to recognize a morally relevant fact as well? Quality of will realists cannot satisfyingly explain why either the morally ignorant father is blameworthy and the factually ignorant father is not, or why the factually ignorant father is excused but the morally ignorant father is not. That is to say they cannot satisfyingly explain the asymmetry.Footnote 22

7 Conclusion

Let me take stock by widening the perspective. The energy of the traditional challenges to moral realism, the arguments from queerness and disagreement (Mackie 1977; Brink 1984), appears to be exhausted. Disagreement is now widely considered irrelevant (Enoch 2009; cf. Doris and Plakias 2008), while queerness seems to be question-begging (Huemer 2005; Enoch 2011). Whether or not this impression is justified is a separate question, and I will take no stand on it here. What matters is that in recent years, several authors have tried to challenge realist accounts of the nature of moral judgment and value from entirely new angles, either by arguing that realism is difficult to defend in light of what we know about the evolutionary origins of our moral norms and values (Street 2006), that it cannot satisfyingly explain why scientific facts cannot be refuted by putative moral facts (Barber 2013) or that, on a realist account, it remains puzzling why there should no so such thing as moral expertise (McGrath 2011; cf. Enoch 2014). Together, these arguments begin to constitute a novel, collaborative challenge to moral realism. The present paper aims to make a contribution to this effort.

Notes

The debate focuses almost exclusively on cases of norm transgressions and blameworthiness, rather than norm compliance (or supererogation) and praiseworthiness [see Rosen (2003) for an example]. I will follow this convention in this paper, with one small exception towards the end of Sect. 5, where I briefly discuss the impact of moral ignorance on folk attributions of praiseworthiness.

See Rosen (2003, 2004, 2008), Guerrero (2007), Fitzpatrick (2008), Levy (2009), Harman (2011, forthcoming) and Robichaud (2014). The recent debate really took off with Rosen’s (2004)-paper. For earlier discussions of similar issues, see Wolf (1982), Buss (1997), Zimmerman (1997) and Montmarquet (1999). In many ways, this debate is also related to and/or foreshadowed by the famous discussion on “inverse akrasia”, see Arpaly (2000, 2002).

http://www.bostonreview.net/books-ideas/martha-c-nussbaum-tragedy-and-justice. Accessed Oct 21, 2015.

My discussion is restricted to cases of non-culpable ignorance. It seems clear that, when the ignorance involved has no claim to a faultless genealogy, the asymmetry collapses: both moral and non-moral ignorance, when culpable, fail to excuse.

Moral facts, according to realism, are supposed to exist independently of anyone’s mental states. But the sense of independence at issue here can only be one of stance-independence (Street 2006), since the fact that Josef Fritzl was a despicable individual is of course not independent of Josef Fritzl’s mental states.

I use “natural” in the literal sense of “these two claims tend to cluster together”, see the empirical evidence compiled by Bourget and Chalmers (2014), where the correlation between cognitivism and realism is the strongest of all (r = 0.562).

One notable exception can be found in Roeser (2011).

Note that Smith’s position, which famously ties moral truths to idealized desires, and thus not to mind-independent facts, does not count as realist in my sense.

I am indebted to Bruno Verbeek for helpful discussions on this point.

A similar proposal is made by Faraci and Shoemaker (2014), 22 with their “difficulty hypothesis”.

I thank an anonymous referee for pointing this out to me.

Compare Sarah McGrath’s strategy in her paper on moral expertise (2011), where she asks: if realism is true, then why is moral expertise so much more controversial than non-moral expertise? My challenge has a similar status.

In healthy adults, cases of genuine moral ignorance may be rare. They are, however, far from non-existent: people who grew up wrapped in all-encompassing twisted belief-systems are value-ignorant; people like the father who poisons his children because he didn’t know that poisoning his children was wrong are judgment-ignorant, even thought such case may be rare indeed. But this need not impress us so much, because the question I am interested in here is whether, and if not why, we would be inclined to excuse him to a comparable degree on the basis of his ignorance in this admittedly far-fetched case. The answer, it seems to me, is ‘no’.

A second but less common argument against the asymmetry which has it that when talking about exculpatory power, we are talking about blameworthiness, and when talking about blameworthiness, we are talking about subjective wrongness. A person can only be blameworthy, the suggestion goes, if she acted in a way that she believed to be wrong. But this suggests that a morally ignorant agent can never be blameworthy, because such an agent thinks, on the basis of the (moral) evidence available to her, that an action is permissible that is not really permissible. However, this argument depends on the premise that if one (falsely) believes something to be permissible, then it cannot be (subjectively) morally wrong—which is equivalent to the claim that moral ignorance exculpates. Therefore, the argument begs the question against defenders of the asymmetry. See Harman (forthcoming), 8.

Note that Rosen’s (2003) examples are only supposed to establish that non-culpable moral ignorance exists. On their own, they do not show that non-culpable moral ignorance has any exculpatory power. This would require specific examples to pump our intuitions. In fact, Rosen frequently admits that this is all he has to appeal to. Notice the pervasive use of mere appeals to intuition: “The example is meant to show that blameless moral ignorance is a possibility. But I should add that in my view it also makes it plausible that insofar as he acts from blameless ignorance, it would be a mistake for us to blame the slaveholder—to feel anger or indignation directed at him for his action. If the historical situation is as we have supposed, then the appropriate attitude is rather a version of what Strawson calls the ‘objective’ attitude. We may condemn the act. We may rail at the universe or at history for serving up injustice on so vast a scale. But in my view it makes no sense to hold this injustice against the per-petrator when it would have taken a miracle of moral vision for him to have seen the moral case for acting differently. It may be hard to believe that moral evil might turn out to be, in the relevant sense, no one’s fault. But so long as we believe that the underlying ignorance is no one’s fault, it seems to me that this is just what we should think” (66).

“Tom is a white male who was raised on an isolated island in the bayous of Louisiana. Growing up, he was taught to believe that all non- white people are inferior and that he has a moral obligation to humiliate them when he gets a chance. As an adult, he decided to become a proud racist, embracing what he was taught. At the age of 25, Tom moves to another town. Walking outside his home, he sees a black man trip and fall. Usually, Tom would spit on the man. But this time, Tom goes against his current moral beliefs, and helps the man up instead” (15).

This is taken into account by some legal systems, where knowledge about certain far-fetched, complicated or new laws is not always assumed.

For the following sample of representative quotes, I am indebted to McGrath (2011).

Perhaps the asymmetry can be “swallowed” by the moral realist by saying that the fact that there is such an asymmetry is a moral fact itself: namely the fact that moral ignorance excuses less than non-moral ignorance. This fact could then be accounted for along familiar realist lines. I do not have a satisfying reply to this, other than that it seems dubiously ad hoc to me. Notice how, if this move is considered legitimate, virtually every phenomenon of the slightest normative significance could be effortlessy accommodated by the moral realist in just this way. Methodologically—considerations of parsimony spring to mind—this strikes me as a slippery slope one would want to avoid.

Thanks to Andreas Müller for pointing this out to me.

A different way of putting this is that our intuitions about the two fathers and comparable cases may track a modal fact. We blame the morally ignorant father more because we can assume, plausibly to my mind, that he will go around poisoning children left and right, in many nearby possible worlds. But this intuition seems mistaken to me, because the example says nothing about the fathers general recklessness in seeking out information about the moral facts, and stipulates that he non-culpably acquired the false moral belief that it is not wrong to poison his children. We therefore have no more reason to think that he will go around poisoning other children than we have with regard to the factually ignorant father.

Thanks to Sebastian Köhler and Daan Evers for helpful discussions on this point.

References

Aharoni, E., Sinnott-Armstrong, W., & Kiehl, K. A. (2012). Can psychopathic offenders discern moral wrongs? A new look at the moral/conventional distinction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(2), 484–497.

Alloy, L. B., & Abramson, L. Y. (1979). Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: Sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 108(4), 441–485.

Anderson, M. (1998). Mental retardation, general intelligence, and modularity. Learning and Individual Differences, 10(3), 159–178.

Arpaly, N. (2000). On acting rationally against one’s best judgement. Ethics, 110(3), 488–513.

Arpaly, N. (2002). Moral worth. Journal of Philosophy, 99(5), 223–245.

Arpaly, N. (2003). Unprincipled virtue: An inquiry into moral agency. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arpaly, N. (2015). Huckleberry Finn revisited: Inverse akrasia and moral ignorance. In R. Clarke, M. McKenna, & A. Smith (Eds.), The nature of moral responsibility. New essays (pp. 141–156). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Audi, R. (2004). The good in the right. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Barber, A. (2013). Science’s immunity to moral refutation. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 91(4), 633–653.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2009). Autism: The empathizing–systemizing (E–S) theory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1156, 68–80.

Blair, R. J. R. (1995). A cognitive developmental approach to morality: Investigating the psychopath. Cognition, 57(1), 1–29.

Blair, R. J. R. (1996). Brief report: Morality in the autistic child. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 26(5), 571–579.

Bortolotti, L. (2009). Delusions and other irrational beliefs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bourget, D., & Chalmers, D. J. (2014). What do philosophers believe? Philosophical Studies, 170(3), 465–500.

Boyd, R. (1988). How to be a moral realist. In G. Sayre-McCord (Ed.), Essays on moral realism. New York: Cornell University Press.

Brink, D. O. (1984). Moral realism and the sceptical arguments from disagreement and queerness. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 62(2), 111–125.

Brink, D. O. (1989). Moral realism and the foundations of ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buss, S. (1997). Justified wrongdoing. Nous, 31(3), 337–369.

Cima, M., Tonnaer, F., & Hauser, M. D. (2010). Psychopaths know right from wrong but don’t care. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 5(1), 59–67.