Abstract

Inflation targeting countries generally define the inflation objective in terms of the consumer price index. Studies in the academic literature, however, reach conflicting conclusions concerning which measure of inflation a central bank should target in a small open economy. This paper examines the properties of domestic, CPI, and real-exchange-rate-adjusted (REX) inflation targeting. In one class of open economy New Keynesian models there is an isomorphism between optimal policy in an open versus closed economy. In the type of model we consider, where the real exchange rate appears in the Phillips curve, this isomorphism breaks down; openness matters. REX inflation targeting restores the isomorphism but this may not be desirable. Instead, under domestic and CPI inflation targeting the exchange rate channel can be exploited to enhance the effects of monetary policy. Our results indicate that CPI inflation targeting delivers price stability across the three inflation objectives and will be desirable to a central bank with a high aversion to inflation instability. CPI inflation targeting also does a better job of stabilizing the real exchange rate and interest rate which is an advantage from the standpoint of financial stability. REX inflation targeting does well in achieving output stability and has an advantage if demand shocks are predominant. In general, the choice of the inflation objective affects the trade-offs between policy goals and thus policy choices and outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a survey, see Walsh (2009).

Monacelli (2013) argues that consumption openness (under perfect exchange rate pass-through) also accounts for the breakdown of the isomorphism result.

Using a symmetric two-country framework, Bodenstein et al. (2012) analyze optimal interest rate responses to headline versus core inflation with endogenous energy prices.

Ball’s model is backward-looking while Svensson’s features both backward-and forward-looking elements. In Svensson’s framework domestic inflation in the Phillips curve is pre-determined so as to allow for a two-period lag of the effect of monetary policy on domestic inflation. This lag pattern is absent in our modelling framework. The real exchange rate channel in Svensson’s Phillips curve is more subdued than in our version. Domestic inflation in period t + 2 is affected by the expected change in the real exchange rate from period t + 1 to period t + 2. This expectation is formed in period t.

The definition of REX inflation differs from Ball’s definition of long-run inflation in one important respect. Ball’s measure relates the level of the lagged real exchange rate to overall inflation while our definition of REX inflation represents domestic inflation adjusted for the degree of supply openness and the change in the real exchange rate. Unlike Ball’s, our definition thus has the natural advantage of being able to distinguish between the REX price level (\( {p}_t^{REX}={p}_t-b{q}_t \)) and the REX inflation rate (\( {\pi}_t^{REX}={\pi}_t-b{\Delta q}_t \)). Froyen and Guender (2014) provides a discussion of the importance of choosing a REX price level target in delegating the conduct of monetary policy to a conservative central banker in an open economy.

In New Zealand, competitors’ price changes—both increases and decreases-- were deemed to be the most important factor in an exporting firm’s decision to change price. Exchange rate changes were found to be an important or very important factor in determining price changes by more than 70 % of exporters among the survey respondents in the United Kingdom. Support for the importance of exchange rate changes as an influence on price setting in the United Kingdom is also provided by Bunn and Ellis (2012a, 2012b).

From the definition of the firm-specific terms of trade and the fact that the firm cannot influence the price set by foreign competitors or the nominal exchange rate it follows that \( \frac{{\partial q(j)}_t}{{\partial p(j)}_t}=-1. \)

Equation (3) is the same as the one proposed by Roberts (1995). Within a general equilibrium framework, the co-movement between marginal cost and economic activity can be established by combining the labor supply and demand relations with the market clearing condition in the goods market. On this point see Clarida et al. (2001); Clarida et al. (2002) or Gali and Monacelli (2005).

For simplicity there is no distinction between the terms of trade and the real exchange rate.

The derivation of the forward-looking IS relation from microeconomic foundations is explained in Guender (2006). A separate appendix, available from the authors, shows how the shocks that appear in the IS relation can be motivated.

The property that all shocks are white noise follows Woodford (1999). Its purpose is to show that gradual adjustment of the output gap, the rate of inflation, etc. are not exclusively tied to the presence of auto-correlated disturbances in the model.

Exclusive reliance on utility-based welfare metrics has drawn some criticism. Clarida et al. ((1999), p.1688) conclude that the micro-founded DSGE New Keynesian approach “could be misleading as a guide to welfare analysis because of its highly stylized microeconomic underpinnings.” Sims (2012) echoes their concerns citing the implausibility of the microeconomic foundations of these DSGE models.

The target for the output gap and the rate of inflation are set at zero.

A step-by-step derivation of all target rules and an explanation of the solution technique employed to determine the forward-looking expectations of inflation, output, and the real exchange rate appear in the appendix which is available upon request from the authors. The coefficients w π , w q , w y are the respective coefficient on the lagged real exchange rate in the putative solution for π t , q t , and y t .

The coefficients ϕ π , ϕ q , ϕ y are the respective coefficient on the lagged real exchange rate in the putative solution for \( {\pi}_t^{CPI},{q}_t, \) and y t .

Arguably, price stability goes beyond keeping one measure of inflation low and stable. In New Zealand, for instance, price stability is defined not solely in terms of CPI inflation but in terms of changes in the general level of prices. This clearly indicates that changes in other price indices figure in the overall assessment of flexible CPI inflation targeting (Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Monetary Policy and the New Zealand Financial System (1992), p. 35).

As analytical solutions do not exist under domestic and CPI inflation targeting these results are established by solving the models numerically. The numerical solutions establish, for instance, that |ϕ π | > |w π |. The effect of the current real exchange rate on expected CPI inflation is greater than on expected domestic inflation. More details on the numerical solution procedure are given in the appendix.

To give precise meaning to the concept of “importance”, we let μ take on values 1, 4, and 8.

The ranking of policy regimes under discretion is not altered by considering optimal policy under commitment from a timeless perspective as in Woodford (1999). In general, the output gap becomes more variable and each rate of inflation less variable under commitment.

For each strategy, the inflation-output variability frontier is constructed by varying the relative weight on the rate of inflation in the objective function; μ takes on values 1, 4, and 8.

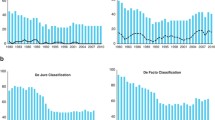

We have also checked the sensitivity of the results reported to a change in the size of b, a key parameter. If supply side openness increases from 0.1 to 0.25, domestic and CPI inflation targeting achieve lower inflation variability at the expense of higher output gap variability. Losses increase somewhat under domestic and CPI inflation targeting but remain invariant under REX inflation targeting. The inflation-output gap variability trade-off frontiers shift up and to the left but the general shape of the frontiers remains similar to those in Figure 1 .

References

Allsopp C, Kara A, Nelson E (2006) United Kingdom inflation targeting and the exchange rate. Economic Journal 116:F232–F244

Aoki K (2001) Optimal monetary responses to relative price changes. J Monet Econ 48:55–80

Ball L (1999) Policy rules for open economies. In: Taylor JB (ed) Monetary policy rules. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 129–156

Benigno G, Benigno P (2006) Designing targeting rules for international monetary policy cooperation. J Monet Econ 53:473–506

Blanchard O, Dell’Ariccia G, and Mauro P (2010) “Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy,” IMF Staff Position Note No. 10/03

Bodenstein M, Guerrieri L, and Kilian L (2012) “Monetary Responses to Oil Price Fluctuations,” unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan

Bunn P, Ellis C (2012a) How do individual UK producer prices behave? Economic Journal 122:F16–F34

Bunn P, Ellis C (2012b) Examining the behavior of individual UK consumer prices. Economic Journal 122:F35–F55

Calvo G (1983) Staggered Prices in a Utility-Maximizing Framework. J Monet Econ 12:383–398

Clarida R, Gali J, Gertler M (1999) The science of monetary policy: a new Keynesian perspective. J Econ Lit 37:1661–1707

Clarida R, Gali J, Gertler M (2001) Optimal monetary policy in open vs. closed economies: an integrated approach. Am Econ Rev 91:248–252

Clarida R, Gali J, Gertler M (2002) A simple framework for international monetary policy analysis. J Monet Econ 49:879–904

Corsetti G, Dedola L, Leduc S (2011) Optimal monetary policy in open economies. In: Benjamin M. Friedman & Michael Woodford (ed.), Handbook of Monetary Economics, edition 1, vol. 3, chapter 16. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 861–933

Curdia V, Woodford M (2011) The central-Bank balance sheet as an instrument of monetary policy. J Monet Econ 58(1):54–79

De Paoli B (2009) Monetary policy and welfare in a small open economy. J Int Econ 77:11–22

Dennis R (2001) ‘Optimal Policy in Rational Expectations Models: New Solution Algorithms,’mimeo, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Engel C (2010) Currency misalignments and optimal monetary policy: a Re-examination. Am Econ Rev 101:2796–2822

Froyen R, Guender A (2007) Optimal monetary policy under uncertainty. Edward Elgar, Cheltingham

Froyen R, Guender A (2014) Price level targeting and the delegation issue in an open economy. Econ Lett 122:12–15

Gali J, Monacelli T (2005) Optimal monetary policy and exchange rate volatility in a small open economy. Review of Economic Studies 72:707–734

Greenslade J, Parker M (2012) New insights into price-setting behaviour in the United Kingdom: introduction and survey results. Economic Journal 122:F1–F15

Guender A (2006) Stabilizing properties of discretionary monetary policies in a small open economy. Economic Journal 116:309–326

Kirsanova T, Leith C, Wren-Lewis S (2006) Should central banks target consumer prices or the exchange rate? Economic Journal 116:F208–F231

Leeper E and Nason J (2015) “Bringing Financial Stability into Monetary Policy,” Sveriges Riksbank Working Paper, 305

Monacelli T (2005) Monetary policy in a low pass-through environment. J Money, Credit, Bank 37(6):1047–1066

Monacelli T (2013) Is monetary policy fundamentally different in an open economy. IMF Economic Review 61:6–21

Parker M (2013) “Price-Setting Behaviour in New Zealand,” unpublished manuscript

Poole W (1970) Optimal choice of monetary policy instrument in a simple stochastic macro model. Q J Econ 84(2):197–216

Reserve Bank of New Zealand (1992) Monetary policy and the New Zealand financial system, 3rd edn. Wellington, New Zealand

Roberts JM (1995) New Keynesian economics and the Phillips curve. J Money, Credit, Bank 27:975–984

Rotemberg J (1982) Sticky prices in the United States. J Polit Econ 90:1187–1211

Sims C (2012) Statistical modeling of monetary policy and its effects. Am Econ Rev 102:1187–1206

Smets F (2014) “Financial stability and monetary policy: how closely interlinked?” European Central Bank Note

Svensson L (2000) Open economy inflation targeting. J Int Econ 50:117–153

Svensson L (2011) Inflation targeting. In: Benjamin M. Friedman & Michael Woodford (ed.), Handbook of Monetary Economics, edition 1, vol. 3, chapter 22. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 1237–1302

Vredin A (2015) “Inflation Targeting and Financial Stability: Providing Policymakers with Relevant Information,” BIS Working Paper, No 503, Bank of International Settlements

Walsh C (2009) Inflation targeting: what have We learned? International Finance 12(2):195–233

Woodford M (1999) “Commentary: How Should Monetary Policy Be Conducted in an Era of Price Stability?” in New Challenges for Monetary Policy: A Symposium Sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, 277–316

Woodford M (2011) Optimal monetary stabilization policy. In: Benjamin M. Friedman & Michael Woodford (ed.), Handbook of Monetary Economics, edition 1, vol. 3, chapter 14. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 723–828

Woodford M (2012) “Inflation Targeting and Financial Stability,” Economic Review 2012:1, Sveriges Riksbank, 7–32

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the editors of this journal for helpful comments. We also appreciate the feedback from seminar participants at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Froyen, R.T., Guender, A.V. What to Aim for? The Choice of an Inflation Objective when Openness Matters. Open Econ Rev 28, 167–190 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-016-9409-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-016-9409-9