Abstract

Facilitating cross-disciplinary research has attracted much attention in recent years, with special concerns in nanoscience and nanotechnology. Although policy discourse has emphasized that nanotechnology is substantively integrative, some analysts have countered that it is really a loose amalgam of relatively traditional pockets of physics, chemistry, and other disciplines that interrelate only weakly. We are developing empirical measures to gauge and visualize the extent and nature of interdisciplinary interchange. Such results speak to research organization, funding, and mechanisms to bolster knowledge transfer. In this study, we address the nature of cross-disciplinary linkages using “science overlay maps” of articles, and their references, that have been categorized into subject categories. We find signs that the rate of increase in nano research is slowing, and that its composition is changing (for one, increasing chemistry-related activity). Our results suggest that nanotechnology research encompasses multiple disciplines that draw knowledge from disciplinarily diverse knowledge sources. Nano research is highly, and increasingly, integrative—but so is much of science these days. Tabulating and mapping nano research activity show a dominant core in materials sciences, broadly defined. Additional analyses and maps show that nano research draws extensively upon knowledge presented in other areas; it is not constricted within narrow silos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanoscale science and engineering is believed to provide for convergence of disparate science and engineering disciplines. If this is the case, such convergence has important implications, not only for nanoscale science but also for governance and regulation of these emerging technological areas (Roco 2006, 2008; Ziegler 2006). Mihail Roco introduced the concept of convergence of multiple disciplines and fields at the nanoscale. His work on “convergence at the nanoscale” put forth the concept of convergence of four broad fields, namely, nanotechnology, biotechnology, cognitive science, and information technology (NBIC) (Roco 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006; Roco and Bainbridge 2003). Research, education, and infrastructure are among the factors that contribute to unification “at the confluence of two or more NBIC domains” (Roco 2004). This convergence of fields was presaged in the National Science and Technology Council’s study of nanotechnology across the globe; this study reported that nanotechnology encompasses a wide range of disciplines, including materials science, physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and engineering (National Science and Technology Council 1999).

Convergence of diverse nano fields has been conceptualized in various ways, reflecting even the divergent top-down and bottom-up approaches of nanotechnology itself. Loveridge et al. (2008) view nanoscale convergence through the lens of nanoscale artefacts (nano-artefacts). Nano-artefacts form the basis for the migration of nanomaterials such as nanotubes into commercial applications in information technology, energy, and nano-medicine. Schmidt (2008) characterizes nanoscale convergence as “techno-object oriented interdisciplinarity.” That is, shared use of instruments and technologies (such as atomic force microscopes, scanning tunneling microscopes, simulation tools, and the like) leads the way for convergence by addressing problem-oriented issues at the boundaries of NBIC fields. In more of a top-down approach, Khushf (2004) suggests that a systems-oriented framework best facilitates the type of convergence represented in the NBIC domain.

However, evidence of an emerging convergence of fields in nanoscale research and commercialization has been mixed. Schummer (2004) conducted co-author analysis and visualization research of 600 publications published in journals deemed nanotechnology-oriented in 2002 and 2003, using the journal subject categories from the Science Citation Index (SCI) of Web of Science. He compares research collaboration patterns in nanotechnology with those of traditional disciplinary research. The results do not show distinctive patterns of interdisciplinarity. He concludes that nanotechnology is an aggregation of otherwise disconnected “mono-disciplinary” fields, rather than multidisciplinary convergence. Meyer (2006) contends that nanotechnology’s conceptualization of converging technologies represents a possible misinterpretation. Cluster analyses of patent data from the US Patent and Trade Office and SCI publications from 1992 to 2001 suggest that there are inter-related and overlapping nanotechnologies connected via instrumentation.

While the above studies question evidence of nanoscale disciplinary convergence, there are other works that have found some signs of cross-disciplinarity at the nanoscale. Grodal and Thoma (2008) identify migration of concepts between nanotechnology and biotechnology. They search for keywords associated with nanotechnology, biotechnology, and the emerging multidisciplinary field of nanobiotechnology in research publications, patents, and product announcements. The authors find that the “nanobiotechnology” keyword activity is growing to a greater extent than that of either of the parent nanotechnology or of the biotechnology fields. Eto (2003) supplements a national evaluation of Japanese nanotechnology government-sponsored projects with bibliometric analysis of journals, citations, and authorship patterns. He finds evidence of multidisciplinarity in nanotechnology centered on chemistry and extending to physics and material sciences and, to a lesser extent, biology and instrument technology.

This existing body of work relating to nano multidisciplinary convergence draws on a variety of definitions, data sources, and findings. Indeed, this variation reflects the state of research examining interdisciplinarity, in general, which encompasses varying definitions, perspectives, and evidence. That said, commitment to interdisciplinary research is notable these days. For instance, the US National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research (http://nihroadmap.nih.gov) includes initiatives that explicitly recognize the importance of interdisciplinary research for future advances. The National Science Foundation’s Nanoscale Interdisciplinary Research Teams program, launched in 2001, seeks to foster interdisciplinary research (IDR) in nanoscale science and engineering by requiring funded projects to have at least three co-principal investigators. Identifying where, how, and whether interdisciplinarity occurs, and could be fostered, may be vital to promote major advances in nanoscience and nanoengineering (hereafter “nano”). Nearly $10 billion has been invested in multiple departments and agencies as part of the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI), including a planned $1.5 billion in fiscal year 2009, so much is at stake in “getting it right.”

Neither there is consensual agreement on the definition of interdisciplinary research (IDR), nor are there widely recognized, valid, and reliable measures of IDR activity or output. Even what to consider as the “disciplines” among which interdisciplinarity would occur is messy. The match between the long-established academic disciplines and current research concentrations is tenuous. Consider psychology, for example; the commonality in research interests and approaches between an experimental psychologist and a clinical psychologist is likely to be rather low. Conversely, that experimental psychologist is apt to identify with research domains such as “neurosciences,” that engage biologists, medical doctors, and so on. Further, there is no universally accepted definition of what constitutes a research field (Zitt 2005). Klein (1999) suggests that specialty interactions may be the preferred indicators of interdisciplinary activity.

Commitment to interdisciplinarity is embodied in the US National Academies Keck Futures Initiative (NAKFI), a 15-year, $40 million effort funded by the W. M. Keck Foundation (www.keckfutures.org). NAKFI anticipates that breakthroughs in research increasingly will occur at the interstices of disciplines, so seeks to promote interdisciplinarity. The US National Academies Committee on Science, Engineering & Public Policy (COSEPUP), Committee on Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research report, Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research (2005) (http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11153) provides an operational definition of IDR essential to our work:

Interdisciplinary research (IDR) is a mode of research by teams or individuals that integrates information, data, techniques, tools, perspectives, concepts, and/or theories from two or more disciplines or bodies of specialized knowledge to advance fundamental understanding or to solve problems whose solutions are beyond the scope of a single discipline or area of research practice. (National Academies Committee on Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research 2005, p. 188)

Our study explores techniques to answer the question: what is the extent and nature of disciplinary diversity in nanoscale research? Certainly, nanotechnology’s fostering of disciplinary convergence must begin with the involvement of multiple fields. We examine the range of fields using a nanotechnology publication dataset that spans 1991–2008. Several methods are introduced to examine multidisciplinarity, including multi-tier mapping and accompanying IDR metrics to help understand the research networking taking place. The results show disciplinary diversity and a range of knowledge sourcing in nanoscale research.

Methods and data

In order to operationalize the concept of interdisciplinarity, this study uses SCI’s journal subject categories (SCs). Morillo et al. (2003), Van Raan (1999), Glanzel et al. (1999), Katz and Hicks (1995), Cozzens and Leydesdorff (1993), Moya-Anegon et al. (2004), and others have used the SCs to study various aspects of cross-disciplinary research knowledge interchange. The SCs match well to the level of “bodies of specialized knowledge or research practice” to which the National Academies Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research Committee (2005) pointed. However, the SCs are imperfect categorizations (c.f., Cozzens and Leydesdorff 1993; Boyack et al. 2005; Leydesdorff 2006). For example, Leydesdorff et al. (1994) and Hicks and Katz (1996) have demonstrated that SCs evolve, making trend comparisons difficult. Moreover, a good portion of journals are linked to two or more SCs, although the majority are categorized into a single SC.

A recent paper (Porter and Rafols, accepted) offers benchmarking analyses of six SCs at four 10-year intervals (from 1975 to 2005). That paper applies the science overlay mapping process (developed by Rafols and Meyer; see also Porter and Rafols 2008; Leydesdorff and Rafols 2009) and draws upon the science mapping of others (Chen 2003; especially Klavans, Borner and Boyack—c.f., Boyack et al. 2005; also Moya-Anegon et al. 2004, 2007). We use these benchmarks, science overlay maps, and IDR metrics to explore the degree of interdisciplinarity in nanotechnology.

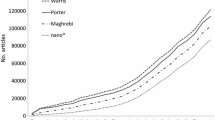

This analysis uses a dataset that identifies nano-related papers by means of a Boolean search in SCI [“nano*,” less exclusions; plus seven additional modules, detailed in this journal by Porter et al. (2008b)]. This inclusive search taps many nano specialties, yielding just over 508,000 SCI articles for the period, 1991–2008 (part-year for 2008). The dataset indicates that the growth of nano publications appears to roughly double every 5 years through 2005, although this exponential trend appears to be easing off in recent years (Fig. 1).Footnote 1

Nanoscience/nanotechnology publications. Source: database extracted from the Web of Science, Science Citation Index, Summer 2008 based on Porter et al. (2008b)

For some analyses, we now take random samples from this “nano” dataset, each containing about 900 papers, for each of 4 years (1991, 1995, 2000, and 2005). As shown in Fig. 1, 900 papers represent a decreasing percentage of the papers published in successive sample years as the amount of nano research is increasing, but this poses no major sampling concerns for our purposes.

Findings

We focus on three areas: (1) research areas (SCs) that are active in nano, presented in tabular and overlay mapping forms; (2) the relationship of research publications to the research they cite in their references; and (3) the extent of integration of these “disciplines” within nano.

Table 1 tallies the Subject Categories in which the greatest number of nano-related papers are published.Footnote 2 These are a subset of the 175 science SCs that are associated with the SCI portion of Web of Science, not including those additional SCs covering the social sciences and humanities. (We are working on a separate study of how nano is treated in the social sciences.) The table lists those SCs that accrue at least 1% of the documentsFootnote 3 in 2005. For 2005, 178 SCs show up with at least one nano publication; 151 SCs have five or more (out of 55,998). For 2008, the new Subject Category for nano, entitled “Nanoscience & Nanotechnology,” is added, and consequently is associated with a sufficiently sizeable number of publications to be included in the top tier nano SCs.

Particular materials sciences, physics, and chemistry SCs dominate the listing. Note that the relative shares of nano publication have shifted over this time period.

-

Most chemistry-related SCs (including chemical engineering) show a substantial increase in share. For the most common chemistry-related SCs—the six chemistry, plus chemical engineering—each increases anywhere from 78% to nearly 900% between 1991 and 2008 (the latter increase is observed for SCs associated with relatively smaller numbers of publications).

-

Materials science SCs, including polymer science, show modest gains, with the exception of the leading SC—materials science, multidisciplinary—which doubles, and materials science, biomaterials, which triples in share.

-

“Bio” related SCs increase as well, but these SCs tend to be starting at smaller levels in 1991; however, there is evidence of a drop-off in Biophysics publications for the partial year 2008 results.Footnote 4

-

Electrical engineering declines dramatically.

-

The two physics SCs with heaviest nano engagement (applied physics and condensed matter physics) decline somewhat (but with a modest rebound in 2008). Physics sub-specialties with lesser nano involvement (including some below the 1% threshold) show a mixed pattern.

We note that Schummer (2007) has also noted shifts in disciplinary emphases within nano research over time—with notable decline for EE and increase for chemistry, but his results do not show the prominence of materials science nearly as strongly as we see here.

Figures 2 and 3 show where nano papers have been published among the SCs. These visualizations overlay the SCs of the nano publications over a base map of science that is also used in Figs. 4 and 5. This base map presents the 175 science SCs—those appear as vertices (points of intersection) in Figs. 2 and 3, and as discernible colored nodes in Figs. 4 and 5. The location of the SCs represents the similarity in citation pattern—if two SCs similarly cite other SCs, they are located close to each other. We have used two approaches to assign SC similarities.

The 175-SC map, as used here, draws upon a cross-journal citation matrix for all SCI publications. That cosine matrix is analyzed using principal components analysis (PCA) to group SCs based on citation pattern similarity. The base map uses the Kamada-Kawai algorithm—available in Pajek to present the resulting pattern in two dimensions. In such maps, location along the axes has no inherent meaning; the representation only conveys relative association among research fields (i.e., closer indicates more association).

The labels in the map are the “macro-disciplines” (i.e., PCA-based factors that group highly associated SCs). Details of the mapping procedures using Pajek are provided in the supplementary information of Leydesdorff and Rafols (2009) and Rafols and Meyer (forthcoming) at www.sussex.ac.uk/spru/irafols (User KIT). Procedures complementing Pajek with VantagePoint are given in the auxiliary appendices with an expanded version of this paper at //tpac.gatech.edu, and elaborated in that expanded version on the website includes color versions of the figures as well. Figures 2 and 3 overlay the nano publication SCs over the base science map, showing its stronger associations as underlying arcs to help discern the nano emphases. Larger nodes reflect more articles. Exercise caution in comparing between the two figures as node sizes have been adjusted to see in which regions the papers concentrate. (Were scaling the same in both figures, the nodes would either overwhelm the map in Fig. 3, or be tiny in Fig. 2, because there are so many more nano articles published in 2005.)

Figures 2 and 3 indicate that the nano distribution is centered on materials science, chemistry, and physics. However, there is significant and sustained nanotechnology activity in particular other areas of biology, medicine, environmental sciences, and geosciences. Moreover, these figures resemble one another suggesting but minor changes in positioning of nano publications across SCs.

In this study of cross-disciplinarity in nanoscience and nano engineering we are also quite interested in the SCs that are heavily cited by the nano publications. Cited SCs provide an indicator of which research areas are contributing knowledge to the nano research—i.e., they show research knowledge transfer patterns.

For part-year 2008, all but 305 of the 30,762 documents retrieved by our nano search of SCI cite at least one reference. Those 30,762 cite an average of 34 references (median, 28; mode, 20). That yields 1,031,757 cited references for which we locate 1,402,203 cited SCs.Footnote 5

For Cited SCs, we have a choice of interpreting either:

-

Records—indicating how many papers reference that SC at least once

-

Instances—indicating the total citations to that SC (i.e., if a particular paper has 20 references to journals associated with a given SC, that counts as 20—whereas it would be a “1” in the Records tally); put another way, a focus on instances provides a “weighting” to the record count.

The distribution of cited SCs encompasses nearly the full complement of 175 science and engineering SCs in SCI. Eighty-eight SCs receive at least 1,000 cites by these 30,457 documents that cite at least one reference (30,762—305) and 151 SCs receive at least 100 cites. If we focus, instead, on “records,” 33 SCs are cited by at least 3,000 of these documents (10%); 57 SCs are cited by at least 1,000 documents and 134 SCs are cited by at least 100. These data suggest that the foundational research knowledge for nanoscience & nanoengineering is highly distributed.

Table 2 lists the top 29 cited SCs with at least 10,000 cites (see the “Instances” column).Footnote 6 Note the record coverage in Table 2. Five Subject Categories are cited at least once by over half of the nano publications and also dominate in terms of number (or percentage) of citation instances. There is a substantial drop from these five to the others in citation instances. Multidisciplinary Sciences is also cited by over half of the publications, but its citation instances are fewer. Subject categories range widely in terms of the number of journals they include, so any cross-SC comparisons should be approached somewhat cautiously. That said, we suggest that these are the core research areas for nano in 2008:

-

Physical Chemistry

-

Multidisciplinary Materials Science

-

Multidisciplinary Chemistry

-

Applied Physics

-

Condensed Matter Physics

Those are also the top five in terms of nano publication frequency in 2005 (Table 1); “Nanoscience & Nanotechnology” joins to make a “Top 6” in terms of nano publication frequency in 2008, but it lags in citation frequency (11th in citation instances; seventh in the % of articles citing an article whose journal is included in the Nanoscience & Nanotechnology SC).

Three SCs rank notably higher in terms of being cited than in their nano publication frequency: Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, Multidisciplinary Sciences (i.e., the SC that holds the elite general science journals, including Science and Nature), and Mathematics (in which only nine of these publications appeared). Quite a few SCs slip in the citation rank compared to their publication rank, notably EE and Metallurgy & Metallurgical Engineering.

A noteworthy set of evidence are nano publications that reference articles from different “macro-disciplines.” A macro-discipline is a grouping of SCs that tend to group together—over all publications in the SCI. These macro-disciplines were constituted based on a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) of SC co-citations by a large general sample of papers indexed in the WOS/SCI (Porter and Rafols, accepted; detailed in the auxiliary appendices located at //tpac.gatech.edu). Just to keep the sample numbers straight, recall that of the 30,762 nano publications for 2008 (part-year), 30,406 have at least one Cited SC (the total shown in Table 3).Footnote 7

The top row of Table 3, labeled “Total publication %,” shows the macro-disciplines of the journals in which these papers appear. Materials Science dominates (63%), followed by Chemistry (23%). Physics, Biomedical Sciences, and Engineering Sciences trail at 10%, 9%, and 8%, respectively. The second row, “Total citation %,” shows the distribution of macro-disciplines based on the journals cited by the 30,406 papers. The same five macro-disciplines dominate, but note the richer interplay. For example, 64% of the papers cite at least one reference from Biomedical Sciences. The next tier of macro-disciplines—Clinical Medicine, Computer Sciences, Agricultural Sciences, and Environmental Science & Technology—are cited by 14–18% of the papers. This cross-macro-discipline citation pattern supports the hypothesis that nano research draws upon widely distributed research knowledge, not just that in “nearby” research fields (i.e., Subject Categories).

The subsequent rows of Table 3 present snapshots of the papers associated with each macro-discipline. For instance, 7,020 papers appear in a journal associated with an SC bundled into the Chemistry macro-discipline. Of those papers, 96% cite at least one such Chemistry article and nearly as many, 91%, cite at least one Materials Science article. Note the rich engagement by Chemistry articles of other macro-disciplines as well: 77% cite a work from Biomedical Sciences and 58% from Physics. One can conclude from these data that the Chemistry subset of the nano publications do not just draw narrowly upon Chemistry research knowledge. This general citation pattern holds for the other macro-disciplines as well. Papers published in one macro-discipline richly cite papers from other macro-disciplines.

For the Top 10 macro-disciplines (those with at least 1% of these nano publications), we summed the percentages across all the macro-disciplines cited at least once, subtracted the percentage referencing that given macro-discipline, and divided by that percentage of papers referencing the given one. These ratios range from 3.7 for Materials Sciences to 6.4 for Civil Engineering. For example, the summation of percentages across the Chemistry row of Table 3 = 489. We subtract 96 (which represents the percentage of papers that cite 1 or more articles published in Chemistry macro-discipline journals) and divide by 96 to get 4.1. We do not want to make too much of this calculated value, but it does offer one perspective on the richness of the reach by nano articles in drawing upon research knowledge from other macro-disciplines.

One consideration of this aspect of the analysis has to do with the empirical construction of the macro-disciplines and the extent to which they may mask the diversity of disciplinary positioning and linkage. Because the macro-disciplines have been composed empirically using PCA (factor analysis), SCs with “chemistry” in their name, for example, are not automatically assigned to the macro-discipline named “chemistry.” It is useful to underscore that five of the top six SCs are associated with Materials Sciences, including two named “physics” and one named “chemistry.” (The list of which SCs are grouped into which macro-disciplines is available in the auxiliary appendices as Table 2, on our website: //tpac.gatech.edu. Also present there is Table 3 which shows the instances of citations to each macro-discipline.) This casts “nano” in a somewhat different light—as heavily concentrated in Materials Sciences. Table 3 affirms the dominant position of Materials Sciences in the citations by the 2008 nano publications. The top two rows of Table 3 also convey the preponderance of Materials Sciences in terms of where nano research is published and that it is the most often cited research. Figures 2 and 3 further underscore this central positioning of articles in or near the Materials Science region on the nano publication overlay maps in 1991 and 2005, regardless of whether the articles are grouped into the Physics or Chemistry macro-disciplines.

Examining “snapshots” of the most prevalent disciplines offers an additional perspective on the diversity of knowledge flow patterns within the nano research community. We now focus on nano articles published in each of the five most common SCs in 2008. And, to obtain a clearer picture, we focus on only those articles whose journal is associated solely with a single SC. We then mapped (1) the top tier of 12 most frequently cited SCs; and (2) a second tier of the top 25 most frequently appearing SCs. (All maps, in color, are available in the auxiliary appendices located at //tpac.gatech.edu.)

The results suggest that:

-

Multidisciplinary Chemistry most commonly cites articles from the Materials Sciences macro-discipline, with a notable extension into the Biomedical Sciences. Its secondary concentration of citations demonstrates extensive reach into the Biomedical Sciences, Chemistry, Health Sciences, and Mathematics.

-

Physical Chemistry papers also heavily cite Materials Sciences, with extensions into Biomedical and Environmental Sciences.

-

Multidisciplinary Materials Sciences, as well, heavily cites Materials Sciences, with singular outreach to Multidisciplinary Sciences (this SC includes Science, Nature & PNAS) and Mathematics. Secondary concentrations of citations link into two areas of Clinical Medicine.

-

Applied Physics shows a strong influence of Materials Sciences, as well as Physics, Chemistry, Electrical Engineering, and Multidisciplinary Sciences. Secondary linkages are related to several Biomedical and Engineering Sciences SCs and to Computer Sciences.

-

Condensed Matter Physics likewise shows concentration of its citations in the Materials Sciences and near-neighbors, Multidisciplinary Sciences, and Electrical Engineering. Secondary linkages touch on Agricultural Science and Mathematics.

Figures 4 and 5 present two network overlay maps that correspond to “snapshots” of two of these SCs within nano: Applied Physics and Physical Chemistry.Footnote 8 The base science map nodes represent the same 175 SCs as in Figs. 2 and 3. Here, they are shown as colored dots that match the macro-disciplines with which they are most associated. In each map, we have selected a single subset of nano publications associated with one SC. We then show arrows from that SC to those SCs that this subset most highly cites—i.e., the key research knowledge upon which those articles draw. (Similar maps for the other three leading SCs and for “top 25” cited SCs for all five SCs appear on our website—//tpac.gatech.edu.)

Even though one of these maps is a physics subfield, and the other chemistry, both maps have a concentration of citations in and around the Materials Science macro-discipline. At the same time, there is a diversity of reach toward knowledge in fields outside the Materials Science neighborhood, with the Applied Physics map showing linkages into electrical engineering, and the Physical Chemistry map connecting into environmental and biosciences. (Both connect to the field “Multidisciplinary Sciences” which corresponds to journals such as Science and Nature.) These visualization mechanisms reinforce the notion that the core nano disciplines cluster closely with the Materials Sciences.

At the same time, nano research draws upon knowledge distributed across a range of disciplines. Indeed, the nano overlay maps in Figs. 2 and 3 touch into virtually the full spectrum of science represented in SCI; 151 of the 175 SCs comprise five or more nano publications in 2005 alone. Yet, the knowledge integration can also be characterized as selective—witness the differences in the citation patterns of the nano physics and chemistry subfield mapped, respectively, in Figs. 4 and 5.

Interdisciplinarity metrics

We have presented indications of cross-disciplinary nano research interconnections through citations in tables and science maps. These indications suggest that nano has a focal concentration in the Materials Sciences, but wide dispersion as well. One could surmise quite different research knowledge exchange mechanisms at work. At one extreme, one might have nano research in certain disciplines drawing almost completely upon research within that one domain. Conversely, one could imagine that nano in one research field (e.g., published in journals linked to one SC) draws upon “every” nano-relevant field. Here, we probe the extent to which individual papers draw upon research from diverse research fields (SCs). To do so, we introduce a measure to gauge the degree of interdisciplinarity in nanotechnology.

Researchers have rich and varied notions about what constitutes interdisciplinary research. We earlier presented the National Academies Committee on Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research (2005) definition that emphasizes integration of knowledge. We have devised a way to measure this concept based on the degree to which a body of research draws upon disparate bodies of knowledge, as reflected by the range of SCs it cites (Porter et al. 2006, 2007, accepted). We gauge this by associating the cited reference journals to SCs. Articles that cite widely dispersed SCs more heavily are deemed more integrative (i.e., more interdisciplinary).Footnote 9 This metric draws on a body of work ranging from Stirling’s (2007) diversity framework to Salton’s cosine measure of similarity between particular SCs (Salton and McGill 1983; Ahlgren et al. 2003).Footnote 10 We have calculated Integration scores for random samples of the nano publications in years spanning the 1991–2008 timeframe. Figure 6 shows moderately high levels of Integration for nano-related articles, increasing over time. We base “moderately high” on comparison with samples of research not restricted to nano, to be discussed shortly (see Table 5). As per footnote 10, Integration scores can range from 0, for a paper that cites only articles published in a single SC, to 1, for extremely wide distribution across diverse SCs.

Average integration scores for samples of nano articles. Note: On the basis of randomized samples of nano-related articles from SCI; the number of articles in each yearly sample ranges from 796 to 872 articles. Source: Samples from nano-database described in Porter et al. (2008b)

Table 4 presents Integration averages for subsets of the top six SC nano-subsets.Footnote 11 The results show that all of these average Integration scores are quite close, suggesting that knowledge sourcing behavior does not vary widely among these six subsets of nano research. Just to provide some statistical benchmarks, a t test between the least Integrative SC (Physics, Condensed Matter) and the most Integrative (Chemistry, Multidisciplinary) is significant. However, a t test between the next lowest (Nano S&T) and the most Integrative (Chemistry, Multidisciplinary) is not quite significant (p = 0.06). Given that nearly all such individual comparisons are not significant, we do not make much of these differences. We also tested variations in integration scores for nano publications that appear in journals associated with a single SC versus those associated with multiple SCs, under the theory that articles published in journals associated with multiple SCs would seem likely to be more interdisciplinary than those associated with a single SC. However, we did not find substantial differences between single-SC and multiple-SC sets of nano publications.Footnote 12

To give some feel for these Integration scores, Appendix 1 includes the set of cited journals, and the cited SCs, for one nano article chosen because its Integration score is closest to the sample average of 0.64 for 2008. This “average” paper is really quite striking in the degree of cross-disciplinary citation. Published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, it cites papers from 16 SCs, including biophysics, biomedical engineering, genetics, multidisciplinary materials science, mathematical & computational biology, and applied physics.

Do these integration scores represent a distinctive pattern of interdisciplinarity within nano publications or are they the result of trends toward interdisciplinarity in the broader research enterprise? To address this question, we have calculated integration scores for article samples from selected SCs that represent science and engineering research in the general set of all publications indexed by Web of Science (including SCI). We have selected six SCs in the general science and engineering research publication index to benchmark at 10-year intervals, 1975–2005 (Porter and Rafols, accepted). One of these benchmark SCs—Physics, Atomic, Molecular & Chemical—is prominently represented in the nano publications (it is the 11th most common subject category) for 2008; its Integration scores in 1995 average 0.56, rising to 0.60 in 2005; these scores are very similar to this SC’s nano publication scores (average 0.56 in 1995 and 0.61 in 2005). For additional comparison, Table 5 gives the other average integration scores for the six general benchmark SCs. Mathematics stands apart as more disciplinary (i.e., researchers in Mathematics primarily draw upon research knowledge associated with Math—they tend to reference other Math articles). These scores suggest that nano-related articles are quite interdisciplinary, but “general” (i.e., not specifically nano) research also tends to be quite interdisciplinary these days.

Conclusions

One of the key characteristics of the nano vision is that it is ‘convergent,’ in the sense that it brings together different sciences and technologies into a single field. This convergence has been expected to lead to an increase in interdisciplinarity in research at the nanoscale. It also has science policy and human capital implications for the development of educational programs and training approaches. There are consequences as well for governance regimes that must incorporate diverse R&D and regulatory policies, and allow for flexibility of structures and approaches.

This study weighs in with evidence about the extent of convergence through two approaches. First, we used a new “map of science” approach, devised by Rafols, Leydesdorff, and Meyer (Rafols and Meyer, forthcoming) to visualize the position of emerging technologies across disciplines. The map is based on similarity measures in the aggregated citing patterns of “scientific disciplines” as measured by using Web of Science Subject Categories. Applied to nano, these visualizations suggest that nano exhibits a high degree of disciplinary diversity. Nano publication centers on materials science (and chemistry and physics). However, nano also significantly involves many other fields, including biomedical sciences, computer sciences & math, environmental sciences, and engineering, among others.

Most importantly, this study shows that nano publications cite, and therefore draw knowledge from, multiple disciplines. Citation patterns show extensive referencing across macro-disciplines (not just across Subject Categories within a macro-discipline). Put inversely, this means that nano researchers do not operate within narrow silos. Nano-related articles in, for instance, chemistry journals integrate knowledge that draws upon research in multiple non-chemistry fields as well. As per Table 3, the preponderance of references in nano-related articles are to research outside the macro-discipline in which the article is published.

Second we presented integration scores as another means to gauge interdisciplinarity. These scores indicate high levels of integration for nano publications, although a similar dynamic was shown in the set of general science and engineering benchmark publications. Still, the integration results are in agreement with case studies of particular nanotechnologies. Some of these technologies represent highly interdisciplinary topics, for example, lab-on-a-chip, merging nanofabrication with microfluidics and biological applications (Rafols 2007). Others appear much more focused, even when the application of this research has implications for very different fields. For example, most research on quantum dots occurs in the materials science/physics zone, although it has major biological applications.

Some questions about the degree of nano interdisciplinarity remain. The high integration scores in the general sample of science and engineering publications raise questions as to whether nano’s interdisciplinarity is a function of what is going on in the broader research enterprise or whether there is something specific to it. Moreover, our maps of science demonstrate that the distribution of nanotechnologies on the map has remained relatively constant from 1991 to 2005, suggesting no noticeable increase in disciplinary diversity, even as the integration scores rise in citation of diverse disciplines. (On the other hand, recall that Table 1 shows important shifts in nano research concentrations over time—with notable increases in chemistry.)

Nanotechnology is, at this point in time, a multidisciplinary collection of fields. These fields, in turn, draw on, and integrate knowledge from, a wide range of diverse fields in different ways. For instance, as per Figs. 4 and 5, note that these two nano sub-fields share emphases on knowledge resources in the materials science neighborhood, but evidence differential outreach to additional other research areas. Materials science, broadly and inclusively defined, serves as a central macro-discipline around which this interdisciplinary knowledge sourcing is taking place. We do not know at this juncture whether the component nano research fields are essentially converging. Future research could examine these questions by focusing on the disciplinary diversity and network coherence of nano sub-topics [e.g., Rafols has been studying kinesin (a molecular motor) research]. Sharpened focus could enable identification of the local areas where knowledge integration is occurring.

The present findings suggest that as part of the future development of nanoscience and nanoengineering, attention needs to be paid to facilitating the diffusion and absorption of research across disciplines. Our findings emphasize the importance of assisting researchers’ ability to source knowledge from disparate areas. Potential barriers to cross-disciplinary knowledge sourcing are many, including difficulties of locating and understanding relevant research in other disciplinary contexts. Sharing relevant research across disciplines has long been fostered by mechanisms such as review articles that summarize findings in a given area.

We suggest two additional paths to nurture cross-disciplinary research. First, to enhance understanding of findings in other disciplines, we encourage attention be given to the language used to present essential findings. Authors and editors should strive to assure that the essential findings of nano-relevant research are presented so as to be as accessible as possible to researchers from other disciplines. For instance, work presented in a materials science journal may well hold high value for a nano-bio researcher. Minimizing jargon and acronyms (and we know that we use them here!), and checking understandability by researchers from other disciplines, should reduce the barriers to nano research knowledge transfer.

Second, to enhance the ability to locate relevant nano research, we encourage exposure to, if not training in, “infometrics” tools and methods to better locate relevant research by using leading databases, such as SCI, INSPEC, EI Compendex, and Chem Abstracts. Enhanced infometrics capabilities can allow researchers to efficiently identify applicable research beyond their immediate field. Furthermore, such skills can allow them to generate research profiles (Porter et al. 2002). Those provide “big picture” landscapes in which to position their own research. Such outreach can help connect to empirical findings, conceptual models, and methods/tools novel to their own research areas. By fostering cognitive cross-disciplinary relationships in these ways, we anticipate that the progress of nanotechnology research can only be enhanced.

Notes

The original Georgia Tech searches were done in 2006. These were updated for Science Citation Index in Summer, 2008. Tallies are 62,351 (2006) and 63,283 (2007). These are apt to increase marginally as SCI continues to index publications that lag somewhat.

The full Table A1 is appended for review purposes; that table will be made available on our website.

For comparisons on random samples of ~900 records each, results correspond closely if we restrict the tally to “articles only”; here we report for all document types captured in SCI.

The 2008 tally of 30,762 records through summer; this is likely to be about half the eventual total publications for the year.

Not all references show up as SCs. To be tallied, the reference must be to a journal; that journal must be indexed by SCI; and our thesaurus must successfully recognize that journal-to-SC match. The thesaurus captures a high percentage of journals that are heavily cited, but does not do so on the low-frequency citations. This reflects the highly skewed journal citation pattern (and this is typical). For instance, one journal (“Phys Rev B”) is cited 35,112 times by these documents; in contrast, 31,495 sources are cited only once. Furthermore, most of those rarely cited sources are not WOS journals.

Just to mention three SCs that are not listed but were cited by a high percentage of the publications—crystallography (by 4436); instruments and instrumentation (by 3975); and chemistry, applied (by 3815).

In considering Table 3, one should keep in mind that 39% of papers are associated with multiple SCs and 30,179 have at least three Cited SCs, the minimum used in calculating interdisciplinarity metrics.

The science overlay mapping procedure was developed by Rafols and Meyer (forthcoming), working with Leydesdorff (c.f., Leydesdorff and Rafols 2009).

The formula for Integration can be expressed as:

$$ I = 1 - \sum\limits_{i,j} {p_{i} p_{j} s_{ij} } $$where p i is the proportion of references citing the SC i in a given paper. The summation is taken over the cells of the SC × SC matrix. s ij is the cosine measure of similarity between SCs i and j (the cosine measure may be understood as a variation of correlation). Here this matrix s ij is based on a US national co-citation sample of 30,261 papers from Web of Science. More details are provided in appendices with an expanded version of this paper at //tpac.gatech.edu.

We considered, but did not adopt, the refinement proposed by Boyack et al. (2005), as our cosine values derive from very large samples. We particularly thank Klavans and Boyack for advice on enhancing our original Integration formulation to that used herein, and on our mapping. We continue to work toward improving our interdisciplinary scoring calibration, so the exact numbers reported here should be interpreted with caution.

Our original notion was to compare for the top six SCs, but then we noted that five of those are associated with the same Macro-Discipline (Materials Sciences).

We have not run ANOVA, but would be very surprised were that to show significant differences for the set of six SCs compared.

References

Ahlgren P, Jarneving B, Rousseau R (2003) Requirement for a cocitation similarity measure, with special reference to Pearson’s correlation coefficient. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 54(6):550–560. doi:10.1002/asi.10242

Boyack KW, Klavans R, Börner K (2005) Mapping the backbone of science. Scientometrics 64(3):351–374. doi:10.1007/s11192-005-0255-6

Chen C (2003) Mapping scientific frontiers: the quest for knowledge visualization. Springer, London

Cozzens S, Leydesdorff L (1993) The delineation of specialties in terms of journals using the dynamic journal set of the SCI. Scientometrics 26:135–156. doi:10.1007/BF02016797

Eto H (2003) Interdisciplinary information input and output of nano-technology project. Scientometrics 58(1):5–33. doi:10.1023/A:1025423406643

Glanzel W, Schubert A, Czerwon J-J (1999) An item-by-item subject classification of papers published in multidisciplinary and general journals using reference analysis. Scientometrics 44(3):427–439. doi:10.1007/BF02458488

Grodal S, Thoma G (2008) Cross-pollination in science and technology: concept mobility in the nanobiotechnology field. Paper presented at the NBER conference on emerging industries: nanotechnology and nanoindicators, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1–2 May 2008

Hicks DM, Katz JS (1996) Where is science going? Sci Technol Human Values 21(4):379–406. doi:10.1177/016224399602100401

Katz JS, Hicks D (1995) The classification of interdisciplinary journals: a new approach. In: Koenig MED, Bookstein A (eds) Proceedings of the fifth international conference of the international society for scientometrics and informetrics. Learned Information, Melford

Khushf G (2004) Systems theory and the ethics of human enhancement—a framework for NBIC convergence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1013:124–149. doi:10.1196/annals.1305.007

Klein JT (1999) Crossing boundaries: knowledge, disciplinarities, and interdisciplinarities. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville

Leydesdorff L (2006) Can scientific journals be classified in terms of aggregated journal-journal citation relations using the journal citation reports? J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 57(5):601–613. doi:10.1002/asi.20322

Leydesdorff L, Rafols I (2009) A global map of science based on the ISI subject categories. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 60(2):348–362. doi:10.1002/asi.20967

Leydesdorff L, Cozzens S, Van den Besselaar P (1994) Tracking areas of strategic importance using scientometric journal mappings. Res Policy 23:217–229. doi:10.1016/0048-7333(94)90054-X

Loveridge D, Dewick P, Randles S (2008) Converging technologies at the nanoscale: the making of a new world? Technol Anal Strateg Manag 20(1):29–43. doi:10.1080/09537320701726544

Meyer M (2006) What do we know about innovation in nanotechnology? Some propositions about an emerging field between hype and path-dependency. Paper presented at the 2006 technology transfer society conference, Atlanta, Georgia, 27–29 Sept

Morillo F, Bordons M, Gomez I (2003) Interdisciplinarity in Science: a tentative typology of disciplines and research areas. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 54(13):1237–1249. doi:10.1002/asi.10326

Moya-Anegon F, Vargas-Quesada B, Herrero-Solvana V, Chinchilla-Rodriguez Z, Corera-Alvarez E, Munoz-Fernandez FJ (2004) A new technique for building maps of large scientific domains based on the cocitation of classes and categories. Scientometrics 61:129–145. doi:10.1023/B:SCIE.0000037368.31217.34

Moya-Anegon F, Vargas-Quesada B, Chinchilla-Rodriguez Z, Corera-Alvarez E, Munoz-Fernandez FJ, Herrero-Solvana V (2007) Visualizing the marrow of science. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 58(14):2167–2179. doi:10.1002/asi.20683

National Academies Committee on Facilitating Interdisciplinary Research, Committee on Science, Engineering, Public Policy (COSEPUP) (2005) Facilitating interdisciplinary research. National Academies Press, Washington

National Science and Technology Council (1999) In: Siegel RW, Roco MC (eds) Nanostructure science and technology: a worldwide study. National Science and Technology Council, Washington

Porter AL, Rafols I (2008) Science overlay maps: easy-to-use tools to help visualize and track bodies of research, a deeper look at the visualization of scientific discovery in the federal context (a workshop at the national science foundation), Washington, DC, 11–12 Sept 2008

Porter AL, Kongthon A, Lu J-C (2002) Research profiling: improving the literature review. Scientometrics 53:351–370. doi:10.1023/A:1014873029258

Porter AL, Roessner JD, Cohen AS, Perreault M (2006) Interdisciplinary research—meaning, metrics and nurture. Res Eval 15(3):187–195. doi:10.3152/147154406781775841

Porter AL, Cohen AS, Roessner JD, Perreault M (2007) Measuring researcher interdisciplinarity. Scientometrics 72(1):117–147. doi:10.1007/s11192-007-1700-5

Porter AL, Rafols I, Meyer M (2008a) The cognitive geography of nanotechnologies: locating nano-research in the map of science. Paper Presented at the NBER conference on nanotechnology and nanoindicators, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1–2 May 2008

Porter AL, Youtie J, Shapira P, Schoeneck DJ (2008b) Refining search terms for nanotechnology. J Nanopart Res 10(5):715–728. doi:10.1007/s11051-007-9266-y

Porter AL, Rafols I Is science becoming more interdisciplinary? Measuring and mapping six research fields over time. Scientometrics (accepted)

Porter AL, Roessner JD, Heberger AE How interdisciplinary is a given body of research? Res Eval (accepted)

Rafols I (2007) Strategies for knowledge acquisition in bionanotechnology: why are interdisciplinary practices less widespread than expected? Innov Eur J Soc Sci Res 20(4):395–412

Rafols I, Meyer M Diversity and network coherence as indicators of interdisciplinarity: case studies in bionanoscience. Scientometrics (forthcoming)

Roco MC (2002) Coherence and divergence of megatrends in science and engineering. J Nanopart Res 4(1–2):9–19. doi:10.1023/A:1020157027792

Roco MC (2003) Nanotechnology: convergence with modern biology and medicine. Curr Opin Biotechnol 14(3):337–346. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(03)00068-5

Roco MC (2004) Nanoscale science and engineering: unifying and transforming tools. AIChE J 50(5):890–897. doi:10.1002/aic.10087

Roco MC (2006) Progress in governance of converging technologies integrated from the nanoscale. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1093:1–23. doi:10.1196/annals.1382.002

Roco MC (2008) Possibilities for global governance of converging technologies. J Nanopart Res 10(1):11–29. doi:10.1007/s11051-007-9269-8

Roco MC, Bainbridge WS (2003) Converging technologies for improving human performance: nanotechnology, biotechnology information technology and cognitive science. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Salton G, McGill MJ (1983) Introduction to modern information retrieval. McGraw-Hill, Auckland

Schmidt JC (2008) Tracing interdisciplinarity of converging technologies at the nanoscale: a critical analysis of recent nanotechnosciences. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 20(1):45–63. doi:10.1080/09537320701726577

Schummer J (2004) Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and patterns of research collaboration in nanoscience and nanotechnology. Scientometrics 59:425–465. doi:10.1023/B:SCIE.0000018542.71314.38

Schummer J (2007) The globalization of nanotechnology research: a bibliometric approach to the assessment of science policy. Scientometrics 70(3):669–692. doi:10.1007/s11192-007-0307-1

Stirling A (2007) A general framework for analysing diversity in science, technology and society. J R Soc Interface. doi:10.1098/rsif.2007.0213

Van Raan AFJ (1999) The interdisciplinary nature of science: theoretical framework and bibliometric-empirical approach. In: Weingart P, Stehr N (eds) Practising interdisciplinarity. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Ziegler AS (2006) Regulation: threat to converging technologies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1093:339–349. doi:10.1196/annals.1382.022

Zitt M (2005) Facing diversity of science: a challenge for bibliometric indicators. Measurement 3(1):38–49

Acknowledgments

Significant research assistance in data treatment, software to facilitate the analyses, and development of visualizations was provided by Jon Garner and Webb Myers. The authors received helpful comments and advice from Ismael Rafols and Philip Shapira. This research was undertaken at Georgia Tech with support by the Center for Nanotechnology in Society (Arizona State University), supported by the National Science Foundation (Award No. 0531194) and the National Partnership for Managing Upstream Innovation: The Case of Nanoscience and Technology (North Carolina State University; NSF Award No. EEC-0438684). The findings and observations contained in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1: Citations by a 2008 nano article whose integration score is at the sample average of 0.638

Appendix 1: Citations by a 2008 nano article whose integration score is at the sample average of 0.638

The selected paper is:

Afonin, K.A., Cieply, D.J., and Leontis, N.B. (2008), Specific RNA self-assembly with minimal paranemic motifs, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 130, p. 93–102.

Cited titles (journals and other sources)

-

Angew Chem Int Ed

-

Annu Rev Biophys Biom

-

Bionanotechnology Le

-

Biophys J

-

Chem Biol

-

Crit Rev Bioch Mol

-

Curr Opin Biotechnol

-

Curr Opin Struc Biol

-

Genet

-

J Amer Chem Soc

-

J Biomol Struc Dyn

-

J Mol Biol

-

J Theor Biol

-

Nanotechnol

-

Nat

-

Nucl Acid Res

-

Org Biomol Chem

-

Proc Nat Acad Sci U

-

Proc Nat Acad Sci USA

-

Sci

-

Unpub

Cited subject categories: based on associating the above journal titles to WOS Subject Categories using our thesaurus

-

Biochemical Research Methods

-

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

-

Biology

-

Biophysics

-

Biotechnology & Applied Microbiology

-

Cell Biology

-

Chemistry, Multidisciplinary

-

Chemistry, Organic

-

Engineering, Biomedical

-

Engineering, Multidisciplinary

-

Genetics & Heredity

-

Materials Science, Multidisciplinary

-

Mathematical & Computational Biology

-

Multidisciplinary Sciences

-

Nanoscience & Nanotechnology

-

Physics, Applied

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Porter, A.L., Youtie, J. How interdisciplinary is nanotechnology?. J Nanopart Res 11, 1023–1041 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-009-9607-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-009-9607-0