Abstract

The scope anomaly observed in sentences like Mrs. J can’t live in Boston and Mr. J in LA (¬◊>∧) and No dog eats Whiskas or cat Alpo (¬∃>∨) is known to pose difficult challenges to many analyses of Gapping. We provide new arguments, based on both the basic syntactic patterns of Gapping and standard constituency tests, that the so-called ‘low VP coordination analysis’—the only extant analysis of Gapping in contemporary syntactic theories which accounts for this scope anomaly—is empirically untenable. We propose an explicit alternative analysis of Gapping in Hybrid Type-Logical Categorial Grammar, a variant of categorial grammar which builds on both the Lambek-inspired tradition and a more recent line of work modelling word order via a lambda calculus for the prosodic component. The flexible syntax-semantics interface of this framework enables us to characterize Gapping as an instance of like-category coordination, via a crucial use of the notion of hypothetical reasoning. This analysis of the basic syntax of Gapping is shown to interact with independently motivated analyses of scopal operators to immediately yield their apparently anomalous scopal properties in Gapping, offering, for the first time in the literature, a conceptually simple and empirically adequate solution for the notorious scope anomaly in Gapping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Instances of Gapping with nonfinite verbs can be found with ‘What—me worry?’ sentences and infinitival optatives:

We also find infinitival subject clauses parallel to (ib):

In addition, it has often been observed that there are typically just two remnants in the gapped conjunct. (Remnants are expressions that remain in non-initial conjuncts.) Thus, examples like the following are marginal at best:

Sag (1976) however notes that if the post-verbal remnants contain PPs, the examples sound much better:

We (like other authors) do not attempt to explain why (i) and (ii) differ in acceptability, but assume that a processing basis is responsible for the difference.

If the distributive reading of negation ‘no dog eats Whiskas or no cat eats Alpo’ seems difficult to get for (5c), consider the following, uttered in a ‘no matter which’ type context:

See the discussion on a related issue in Sect. 2.2.1 below.

In (14), the presence of rather seems crucial in making the sentence acceptance. We currently do not know why this is the case, but it seems most likely that this is not a syntactic issue. Note the following attested examples, which seem acceptable without an overt rather (many similar examples were found by a cursory Google search):

See also Vicente (2010) and Toosarvandani (2013a) for some discussion on the properties of corrective but.

Repp’s (2006, 2009) own analysis—the only explicit proposal in the literature addressing this ¬A∧B Gapping pattern—fails to predict the auxiliary wide-scope reading of sentences such as John shouldn’t eat steak and Mary just pizza. The core idea of her proposal is that wide scope negation readings arise as instances of ‘illocutionary negation’, a kind of negation corresponding to a speech act. But since only the negation in this sentence would have this illocutionary force—as vs. should, which denotes a deontic operator with no illocutionary content—only the former could reasonably be assumed to scope over the whole conjunction, predicting, in effect, ¬(□A∧□B) as the meaning of the sentence (where the correct meaning makes a much stronger assertion: □¬(A∧B) ≡ ¬◊(A∧B)). Furthermore, Tomioka (2011) provides examples ((2) on p. 223) exhibiting auxiliary wide-scope interpretations within conditional and relative clauses, a phenomenon that is highly problematic for Repp’s illocutionary negation-based account.

Aside from the question of how to move these items out of the VP to begin with, there is also the issue of how to ensure that the moved elements preserve their relative order with respect to each other. That is, since movement (albeit of a different kind) is involved in removing the verb from the second conjunct, an analogous problem arises as in Johnson’s approach (the difference is that here linearization becomes an issue not for the correlates of the elided material but for the remnants). Since Toosarvandani criticizes Johnson’s account on the basis of the conceptual implausibility of the linearization constraints, invoking the same constraints is not an option for him. But then, we fail to see any way in which the three elements that are removed from the elided VP are properly linearized with respect to each other.

We are aware that island ‘violations’ display a wide range of variability, both from speaker to speaker and in the judgment of the same speakers. In particular, one reviewer for the present paper notes that the particular examples in (24) are not acceptable for him/her. However, given that at least some of the examples listed in the text seem to be quite acceptable for many speakers (for example, we have consulted about seven speakers on the status of (24a) and (24e), and they unanimously found the latter to be impeccable, and the former to be not nearly as acceptable but well within the bounds of acceptability), we believe that such variability does not affect our overall conclusion here that the supposed island sensitivity cannot be used to argue for a movement-based analysis of Gapping.

One reason for this variability in acceptability seems to be whether the examples are presented to the informant with the right prosody. In all of the examples in (24), strong contrastive/parallel stress is required on the corresponding elements in the antecedent and gapped clauses, along with distinct but quite short pauses before the second of these elements. For example, in (24a), lunch and dinner should be contrastively stressed, with the former receiving high/falling pitch, and the latter, following a clipped pause between you and for dinner, pronounced with steady mid-level pitch.

A reviewer notes that (25b) might be ruled out because of an independent constraint on Gapping requiring the remnants to be ‘major sentence constituents’ (Hankamer 1973, 18), but note that this generalization itself needs to be revised since there are well-formed instances of Gapping obviously violating this alleged constraint, such as the determiner gapping examples (4d) and (5c) from McCawley (1993).

This of course does not mean that there are no semantic/pragmatic principles governing the use of do so anaphora. In fact, there are: according to Ward and Kehler (2005), the acceptability difference in examples such as ?The tallest teachers do so by example vs. The greatest teachers do so by example (involving deverbal nouns) depends on whether the nominalization makes the associated event (or property) salient enough to support do so anaphora. The reason that do so has traditionally (but perhaps not totally unproblematically) been taken to be a syntactic constituency test is consistent with this view: if there is an overt syntactic constituent that denotes the relevant property in the preceding discourse, that alone makes the property salient enough. And since there would be nothing semantically or pragmatically incoherent in the denotation of the alleged VP constituent in the case of (28), the prediction follows that, on the low VP coordination analysis, the examples should be grammatical.

One might think that examples like (29) could be ruled out by assuming that reconstruction of the subject of the first conjunct to a VP-internal position (which one might motivate either from the CSC (Lin 2001) or perhaps just for the purpose of semantic interpretation) is blocked for fronted VPs. Such an assumption might in turn be taken to receive independent support from the fact that the object quantifier cannot scope over the subject quantifier in such an environment:

But the argument that (i) motivates this assumption is decisively undermined by contrasts such as that between (iia) and (iib).

In (iib) there is no question of the existentially quantified subject reconstructing to a position within the fronted constituent, since it did not originate within that constituent to begin with. Yet just as in (i), we find that the wide scope available to the in situ universal is unavailable when the universal is part of a topicalized constituent. Hence the claim that subjects cannot reconstruct back into fronted VPs receives no support from the scopal facts about (i), and appealing to such a claim to explain the pattern in (29) must therefore be purely stipulative.

Johnson (2014) claims that the pattern exhibited by (39) is limited to cases in which the two conjuncts have the same tense, based on his judgments on the following:

We do not think that this is a syntactic constraint. Note that the following minimally different example improves over (i) significantly:

To aid the reader’s understanding, we’d like to point out here that the Introduction rules, especially the one for the non-directional slash | that we introduce below, loosely correspond to Move in Minimalism. There are, however, two important caveats. First, conceptually, the Introduction rules in TLCG are inference rules in the deductive system, which means that they, together with the Elimination rules, define the properties of the connectives /, ∖and |, just as the rules in natural deduction formulations of standard logics (such as propositional logic) define the (proof-theoretic) properties of conjunction, implication and other connectives. For this reason, the ‘grammar rules’ in TLCG have very different statuses from ‘corresponding’ rules in other theories. Second, and relatedly, there is also a (by no means trivial) empirical difference as well, which the metaphorical allusion to Merge and Move might obscure: since these rules are not rules for structure building and structure manipulation, having the Introduction and Elimination rules in TLCG as inference rules has a different consequence than having Merge and Move in a derivational setup, a point which we return to below.

Here and elsewhere, calligraphic letters (\(\mathcal{U, V, W, \ldots}\)) are invariably used for polymorphic variables; copperplate letters (\(\mathscr{P, Q, \ldots}\)) are reserved for higher-order variables (with fixed types).

Note also that the generality of the hypothetical reasoning mechanism mediating filler-gap dependency in the present setup entails that, unlike CCG (cf. Steedman 1996), the present proposal does not capture the nested dependency constraint (Fodor 1978) as a syntactic constraint, predicting that both of the following two sentences are licensed by the grammar:

If one desired to capture such a constraint in the grammar itself in a framework like the present one, one way to do so would be to adopt the proposal by Pogodalla and Pompigne (2012), whose key solution involves ‘indexing’ the gap positions and the corresponding fillers by means of subtyping in syntactic categories so that nested dependency configuration results in incoherent typing.

However, we find such a solution to be undesirable, since it also incorrectly rules out examples like the following:

The key difference between examples like (ia) and (ii)–(iii) seems to be that in the latter two cases, there is minimal ambiguity in the possible assignment of fillers to gap sites. In (ii), the syntactic categories of the two filler-gap pairs are different, corresponding to different fixed positions in the valence structure of the selecting head tell. In (iii), the construction itself imposes an ‘abstract property’ interpretation on the complement of like and a ‘concrete individual’ interpretation on the complement of talk to, again minimizing ambiguity effects associated with the two NPs Robin and what. Thus, following, e.g., Fodor (1983) and Pollard and Sag (1994), we take the nested dependency constraint to be essentially a processing-oriented condition, one which takes effect only when there is a potential ambiguity in the linking of the fillers and gaps.

Or, if one desired, this lexical rule could be reformulated as an empty operator of the following form:

This of course does not mean that such pragmatic and prosodic properties can be expressed/realized only in Gapping. As noted by a reviewer, a parallel discourse relation and a Gapping-like prosody is possible in ordinary coordination as well in the right kind of context such as the following:

The difference between Gapping and ordinary coordination is that while the association with this prosody/pragmatics pair is optional in the latter, it is obligatory in the former.

See Kubota (2010, Sect. 3.2.1), Kubota and Levine (2015) and Moot (2014) for extensive discussions on this point. In particular, Moot (2014) discusses the particular difficulty that these approaches face in the context of Gapping (as well as other empirical phenomena such as (ordinary) coordination and adverb modification), where the interpretation ‘Leslie saw Sandy and Bill saw Robin’ is predicted to be available for Leslie saw Sandy, and Robin Bill in a direct translation of the present analysis into ACG/Lambda Grammar.

And to matrix verbs, not embedded verbs; thus, we take it that Johnson’s (2009) ‘no embedding’ constraint on Gapping follows from this.

In connection to this, one might wonder how cross-speaker Gapping like the following is to be handled:

Note that the conjunction marker is obligatory in B’s utterance. We take this fact to indicate that this type of cross-speaker Gapping is felicitous only when the second speaker’s utterance can in effect be interpreted as completing the utterance of the first speaker. As such, we take it that examples like (i) do not constitute counterevidence to our claim that Gapping is a strictly sentence grammar phenomenon licensed in conjunction environments only.

As it is, the analysis of auxiliaries here overgenerates. To capture the clause-boundedness of the scope of auxiliaries, we follow Siegel (1987) and assume that auxiliaries lower into untensed sentences to produce tensed sentences. This can be achieved by positing a binary feature [tns±] for the category S and modifying the lexical entries for auxiliaries along the following lines:

This prevents auxiliaries from lowering into tensed sentences in a long-distance fashion. With (i), the clause that the auxiliary lowers into has to be specified as [tns−] originally, but such an untensed sentence cannot combine with a higher verb subcategorizing for a sentential complement (\(\mathrm {S_{[tns+]}}\)) unless an auxiliary combines with it to change the value of the tns feature from − to +. Thus, auxiliaries are bound to take scope immediately above the local clause, modulo cases involving coordination of untensed sentences, which give rise to the auxiliary wide-scope Gapping sentences, as we show below. The assumption that such Gapping sentences involve coordination of untensed clauses might explain why they allow accusative (instead of nominative) pronouns as subjects of the non-initial conjuncts, as in You can’t eat steak and me just pizza.

Note also that the internal \(\mathrm {VP/VP}\) is specified as \(\mathrm {VP_{[tns{}-]}/VP_{[tns{}-]}}\), not as \(\mathrm {VP_{[tns+]}/VP_{[tns{}-]}}\). This allows us to derive (as desired) the \(\mathrm {VP_{[tns+]}/VP_{[tns{}-]}}\) type derived auxiliary entry in the same procedure as shown in (76) in Appendix A.2.3.

One might wonder at this point whether the present approach can derive the ¬A∧B reading of examples like (14) from the previous section. This can be derived by taking (14) to instantiate a case of discontinuous Gapping where the missing elements in the second conjunct are the auxiliary was and the passive infinitive called (rather than the whole string wasn’t called). Then, by assuming that the contraction of negation on the auxiliary is a surface morpho-phonological process, the string in (14) can be matched with the intended interpretation.

For a recent alternative analysis of split scope, see Abels and Martí (2010). The key component of Abels and Martí’s analysis consists in treating negative quantifiers (and related expressions) as quantifiers over choice functions (of type ((et→e)→t)→t). We believe that this approach is also compatible with the syntax-semantics interface of determiner gapping in our analysis.

Steedman (2012) proposes an analysis of split scope in CCG that embodies a similar idea, though technically implemented in a somewhat different way.

Note that the derivability relation here is asymmetrical: (65) ⊢ (70) is a theorem but (70) ⊢ (65) isn’t.

Note also that, in the present analysis, cases such as (4d) involving non-negative quantifiers are equally straightforward. The only difference from the negative quantifier case outlined in the main text is that non-negative quantifiers have only the ordinary GQ-type lexical entries, and thus, only the latter type of derivation is available for them. This yields the distributive reading for the quantifier. Since split scope is not an issue, so far as we can tell, this suffices to derive the correct truth conditions for sentences like (4d).

References

Abeillé, Anne, Gabriela Bîlbîie, and Francois Mouret. 2014. A Romance perspective on Gapping constructions. In Romance in construction grammar, eds. Hans C. Boas and Francisco Gonzalvez Garcia, 227–265. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Abels, Klaus, and Luisa Martí. 2010. A unified approach to split scope. Natural Language Semantics 18: 435–470.

Carpenter, Bob. 1997. Type-logical semantics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Coppock, Elizabeth. 2001. Gapping: in defense of deletion. In Chicago Linguistics Society (CLS) 37, eds. Mary Andronis, Christoper Ball, Heidi Elston, and Sylvain Neuvel, 133–147. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Culicover, Peter W., and Ray Jackendoff. 2005. Simpler syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dalrymple, Mary, Stuart M. Shieber, and Fernando C. N. Pereira. 1991. Ellipsis and higher-order unification. Linguistics and Philosophy 14(4): 399–452.

de Groote, Philippe. 2001. Towards abstract categorial grammars. In Association for Computational Linguistics, 39th Annual Meeting and 10th Conference of the European Chapter, 148–155.

Deane, Paul. 1991. Limits to attention: A cognitive theory of island phenomena. Cognitive Linguistics 2(1): 1–63.

Dowty, David. 2007. Compositionality as an empirical problem. In Direct compositionality, eds. Chris Barker and Pauline Jacobson, 23–101. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fodor, Janet Dean. 1978. Parsing strategies and constraints on transformations. Linguistic Inquiry 9(3): 427–473.

Fodor, Janet Dean. 1983. Phrase structure parsing and the island constraints. Linguistics and Philosophy 6: 163–223.

Fox, Danny, and David Pesetsky. 2005. Cyclic linearization of syntactic structure. Theoretical Linguistics 31(1–2): 1–46.

Gengel, Kristen. 2013. Pseudogapping and ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hankamer, Jorge. 1973. Unacceptable ambiguity. Linguistic Inquiry 4(1): 17–68.

Hendriks, Petra. 1995. Ellipsis and multimodal categorial type logic. In Formal grammar: European Summer School in Logic, Language and Information (ESSLLI), Barcelona, 1995, eds. Glyn V. Morrill and Richard T. Oehrle, 107–122.

Hofmeister, Philip, and Ivan A. Sag. 2010. Cognitive constraints and island effects. Language 86(2): 366–415.

Hofmeister, Philip, Laura Staum Casasanto, and Ivan Sag. 2012a. How do individual cognitive differences relate to acceptability judgments?: A reply to Sprouse, Wagers, and Phillips. Language 88: 390–400.

Hofmeister, Philip, Laura Staum Casasanto, and Ivan Sag. 2012b. Misapplying working memory tests: A reductio ad absurdum. Language 88: 408–409.

Huang, C. T. James. 1993. Reconstruction and the structure of VP: Some theoretical consequences. Linguistic Inquiry 24(1): 103–138.

Jackendoff, Ray S. 1971. Gapping and related rules. Linguistic Inquiry 2(1): 21–35.

Jacobs, Joachim. 1980. Lexical decomposition in Montague grammar. Theoretical Linguistics 7(1/2): 121–136.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 1990. Incomplete VP deletion and Gapping. Linguistic Analysis 20(1–2): 64–81.

Johnson, Kyle. 2000. Few dogs eat Whiskers or cats Alpo. In University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers (23), eds. Kiyomi Kusumoto and Elisabeth Villalta, 47–60. Amherst: GLSA Publications.

Johnson, Kyle. 2004. In search of the English middle field. Ms., University of Massachusetts, Amherst. http://people.umass.edu/kbj/homepage/Content/middle_field.pdf.

Johnson, Kyle. 2009. Gapping is not (VP-) ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 40(2): 289–328.

Johnson, Kyle. 2014. Gapping. Ms., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Kehler, Andrew. 2002. Coherence, reference and the theory of grammar. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Kluender, Robert. 1992. Deriving island constraints from principles of predication. In Island constraints: Theory, acquisition, and processing, eds. Helen Goodluck and Michael Rochemont, 223–258. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kluender, Robert. 1998. On the distinction between strong and weak islands: A processing perspective. In The limits of syntax, eds. Peter Culicover and Louise McNally. Vol. 29 of Syntax and Semantics, 241–279. San Diego: Academic Press.

Kubota, Yusuke. 2010. (In)flexibility of constituency in Japanese in Multi-Modal Categorial Grammar with Structured Phonology. Ph.D. diss., Ohio State University.

Kubota, Yusuke. 2014. The logic of complex predicates: A deductive synthesis of ‘argument sharing’ and ‘verb raising’. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32(4): 1145–1204.

Kubota, Yusuke. 2015. Nonconstituent coordination in Japanese as constituent coordination: An analysis in Hybrid Type-Logical Categorial Grammar. Linguistic Inquiry 46(1): 1–42.

Kubota, Yusuke, and Robert Levine. 2012. Gapping as like-category coordination. In Logical Aspects of Computational Linguistics 2012, eds. Denis Béchet and Alexander Dikovsky, 135–150. Heidelberg: Springer.

Kubota, Yusuke, and Robert Levine. 2015, to appear. Against ellipsis: Arguments for the direct licensing of ‘non-canonical’ coordinations. Linguistics and Philosophy.

Kubota, Yusuke, and Robert Levine. 2013a. Coordination in Hybrid Type-Logical Categorial Grammar. In OSU Working Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 60, 21–50. Department of Linguistics, Ohio State University.

Kubota, Yusuke, and Robert Levine. 2013b. Determiner gapping as higher-order discontinuous constituency. In Formal Grammar 2012 and 2013, eds. Glyn Morrill and Mark-Jan Nederhof, 225–241. Heidelberg: Springer.

Kubota, Yusuke, and Robert Levine. 2014a. Pseudogapping as pseudo-VP ellipsis. In Logical Aspects of Computational Linguistics 2014, eds. Nicholas Asher and Sergei Soloviev, 122–137. Heidelberg: Springer.

Kubota, Yusuke, and Robert Levine. 2014b. Pseudogapping as pseudo-VP ellipsis. ms. Ohio State University.

Kubota, Yusuke, and Robert Levine. 2014c. Unifying local and nonlocal modelling of respective and symmetrical predicates. In Formal Grammar 2014, eds. Glyn Morrill, Reinhard Muskens, Rainer Osswald, and Frank Richter, 104–120. Heidelberg: Springer.

Kubota, Yusuke, and Robert Levine. 2014d. Scope anomaly of Gapping. In North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 44 GLSA, 247–260.

Kuno, Susumu. 1976. Gapping: A functional analysis. Linguistic Inquiry 7: 300–318.

Lambek, Joachim. 1958. The mathematics of sentence structure. The American Mathematical Monthly 65: 154–170.

Lasnik, Howard. 1999. Pseudogapping puzzles. In Fragments: Studies in ellipsis and gapping, eds. Shalom Lappin and Elabbas Benmamoun, 141–174. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Levin, Nancy S., and Ellen F. Prince. 1986. Gapping and causal implicature. Papers in Linguistics 19: 351–364.

Lin, Vivian. 2000. Determiner sharing. In West Coast Conference in Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 19, eds. Roger Billerey and Brook Danielle Lillehaugen, 274–287. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Lin, Vivian. 2001. A way to undo A movement. In West Coast Conference in Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 20, eds. Karine Megerdoomian and Leora Anne Bar-el, 358–371. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Lin, Vivian. 2002. Coordination and sharing at the interfaces. Ph.D. diss., MIT.

McCawley, James D. 1993. Gapping with shared operators. In Berkeley Linguistics Society, ed. David A. Peterson, 245–253. Berkeley: University of California.

Mihaliček, Vedrana. 2012. Serbo-Croatian word order: A logical approach. Ph.D. diss., Ohio State University.

Mihaliček, Vedrana, and Carl Pollard. 2012. Distinguishing phenogrammar from tectogrammar simplifies the analysis of interrogatives. In Formal Grammar 2010/2011, eds. Philippe de Groote and Mark-Jan Nederhof, 130–145. Heidelberg: Springer.

Montague, Richard. 1973. The proper treatment of quantification in ordinary English. In Approaches to Natural Language: 1970 Stanford Workshop on Grammar and Semantics, eds. Jaakko Hintikka, Julius M. E. Moravcsik, and Patrick Suppes, 221–242. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Moortgat, Michael. 1988. Categorial investigations: Logical and linguistic aspects of the Lambek calculus. Dordrecht: Foris.

Moortgat, Michael. 1997. Categorial Type Logics. In Handbook of logic and language, eds. Johan van Benthem and Alice ter Meulen, 93–177. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Moot, Richard. 2014. Hybrid type-logical grammars, first-order linear logic and the descriptive inadequacy of lambda grammars. ms., Laboratoire Bordelais de Recherche en Informatique.

Morrill, Glyn. 1994. Type Logical Grammar: Categorial logic of signs. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Morrill, Glyn, Oriol Valentín, and Mario Fadda. 2011. The displacement calculus. Journal of Logic, Language and Information 20: 1–48.

Muskens, Reinhard. 2001. Categorial Grammar and Lexical-Functional Grammar. In Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG) ’01, eds. Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong. http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/LFG/6/lfg01.html.

Muskens, Reinhard. 2003. Language, lambdas, and logic. In Resource sensitivity in binding and anaphora, eds. Geert-Jan Kruijff and Richard Oehrle, 23–54. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Muskens, Reinhard. 2007. Separating syntax and combinatorics in categorial grammar. Research on Language and Computation 5(3): 267–285.

Oehrle, Richard T. 1971. On Gapping. ms., MIT.

Oehrle, Richard T. 1987. Boolean properties in the analysis of gapping. In Syntax and semantics: Discontinuous constituency, eds. Geoffrey J. Huck and Almerindo E. Ojeda, Vol. 20, 203–240. San Diego: Academic Press.

Oehrle, Richard T. 1994. Term-labeled categorial type systems. Linguistics and Philosophy 17(6): 633–678.

Partee, Barbara, and Mats Rooth. 1983. Generalized conjunction and type ambiguity. In Meaning, use, and interpretation of language, eds. Rainer Bäuerle, Christoph Schwarze, and Arnim von Stechow, 361–383. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Penka, Doris. 2011. Negative indefinites. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pogodalla, Sylvain, and Florent Pompigne. 2012. Controlling extraction in Abstract Categorial Grammars. In Formal Grammar 2010/2011, eds. Philippe de Groote and Mark-Jan Nederhof, 162–177. Heidelberg: Springer.

Pollard, Carl. 2014. What numerical determiners mean: A non-ambiguity analysis. Talk presented at the Workshop on Semantics of Cardinals, Ohio State University, March 6, 2014.

Pollard, Carl, and E. Allyn Smith. 2012. A unified analysis of the same, phrasal comparatives and superlatives. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 2012, 307–325.

Pollard, Carl J., and Ivan A. Sag. 1994. Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar. Studies in contemporary linguistics. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Repp, Sophie. 2006. ¬(A&B). Gapping, negation and speech act operators. Research on Language and Computation 4(4): 397–423.

Repp, Sophie. 2009. Negation in Gapping. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ross, John Robert. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Ph.D. diss., MIT. Reproduced by the Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Ross, John Robert. 1970. Gapping and the order of constituents. In Progress in linguistics, eds. Manfred Bierwisch and Karl E. Heidolph, 249–259. The Hague: Mouton.

Sag, Ivan. 1976. Deletion and logical form. Ph.D. diss, MIT.

Sag, Ivan A., Gerald Gazdar, Thomas Wasow, and Steven Weisler. 1985. Coordination and how to distinguish categories. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 3(2): 117–171.

Siegel, Muffy E. A. 1984. Gapping and interpretation. Linguistic Inquiry 15(3): 523–530.

Siegel, Muffy A. 1987. Compositionality, case, and the scope of auxiliaries. Linguistics and Philosophy 10(1): 53–75.

Steedman, Mark. 1985. Dependency and coordination in the grammar of Dutch and English. Language 61(3): 523–568.

Steedman, Mark. 1990. Gapping as constituent coordination. Linguistics and Philosophy 13(2): 207–263.

Steedman, Mark. 1996. Surface structure and interpretation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Steedman, Mark. 2012. Taking scope. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Takahashi, Shoichi. 2004. Pseudogapping and cyclic linearization. In North East Linguistics Society (NELS) 34, eds. Keir Moulton and Matthew Wolf, 571–585. University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Graduate Linguistic Student Association.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2011. Review of Negation in Gapping by Sophie Repp. Language 87(1): 221–224.

Toosarvandani, Maziar. 2013a. Corrective but coordinates clauses not always but sometimes. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31: 827–863.

Toosarvandani, Maziar. 2013b. Gapping is low coordination (plus VP-ellipsis): A reply to Johnson. ms., MIT.

Vicente, Luis. 2010. On the syntax of adversative coordination. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 28: 381–415.

Ward, Gregory, and Andrew Kehler. 2005. Syntactic form and discourse accessibility. In Anaphora processing: Linguistic, cognitive, and computational modelling, eds. António Branco, Tony McEnery, and Ruslan Mitkov, 365–384. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Winkler, Susanne. 2005. Ellipsis and focus in generative grammar. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Worth, Chris. 2014. The phenogrammar of coordination. In European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (EACL) 2014 Type Theory and Natural Language Semantics (TTNLS), 28–36. Gothenburg: Association for Computational Linguistics. http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W14–1404.

Yoshida, Masaya, Honglei Wang, and David Potter. 2012. Remarks on “gapping” in DP. Linguistic Inquiry 43(5): 475–494.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we would like to thank our NLLT editor Louise McNally for her very thoughtful editorial guidance, which made going through the reviewing process an intellectually quite challenging, but an utterly pleasant process. Thanks are also due to the three reviewers for NLLT in this regard, whose comments were extremely useful in shaping both the content and the structure of the paper in the final form. In addition, the paper has benefited from discussions and comments from Kyle Johnson, Michael Moortgat, Glyn Morrill, Carl Pollard and William Schuler. We have presented parts of the paper at NELS 44, Logical Aspects of Computational Linguistics 2012, and Formal Grammar 2013. We thank the abstract reviewers and participants of these conferences, as well as the participants of the LLIC discussion group at OSU for their feedback. The first author was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS; PD 2010–2013 and Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad 2013–2014) when he worked on this paper, and would like to thank JSPS for its financial support. The second author thanks the Department of Linguistics and College of Arts and Sciences for grant support during the course of the research for this paper over the past two years.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Deductive rules and ancillary derivations

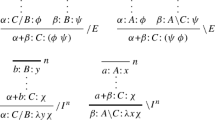

1.1 A.1 Rules of Hybrid TLCG

-

(71)

1.2 A.2 Derivations

1.2.1 A.2.1 Interaction of topicalization and Gapping

First, the gapped string Chris gave can be derived via hypothetical reasoning in the usual manner:

-

(72)

Then the two conjuncts to be coordinated are derived by binding a gap of type \(\mathrm {S/PP/NP}\) in a topicalized sentence (note that two hypothetical reasonings are involved here, one for Gapping and the other for topicalization):

-

(73)

The derivation completes by conjoining two expressions of type \(\mathrm {S|(S/PP/NP)}\) and lowering the type \(\mathrm {S/PP/NP}\) gapped expression to the first conjunct:

-

(74)

1.2.2 A.2.2 Intermediate derivation for auxiliary + verb gapping

We first lower a TV-type constituent (consisting of the verb itself and an unbound variable representing the gap position for the auxiliary) to a gapped sentence of type \(\mathrm {S|TV}\). Then, by binding the \(\mathrm {VP/VP}\) gap for the auxiliary with |, an \(\mathrm {S|(VP/VP)}\) expression is derived which can then be given as an argument to the auxiliary (as in (63) in the main text).

-

(75)

1.2.3 A.2.3 Distributive reading for auxiliary gapping

We first show how a \(\mathrm {VP/VP}\) entry for an auxiliary is obtained from the lexically assigned higher-order entry of type \(\mathrm {S|(S|(VP/VP))}\).

-

(76)

By using this entry, the distributive reading for examples like (58b) can be derived straightforwardly, as in (77).

-

(77)

Appendix B: Full formal analysis of determiner gapping

We assign the following type of lexical entry for negative determiners (= (65)):

-

(78)

We can intuitively make sense of the phonological term assigned to this entry as follows. Since ordinary quantificational determiners are of type st

((st

((st

st)

st)  st), the prosodic type of this type-raised determiner is ((st

st), the prosodic type of this type-raised determiner is ((st

((st

((st

st)

st) st))

st)) st)

st) st. The right form of this higher-order phonology of a type-raised determiner can be inferred from the phonological term that is assigned to a syntactically type-raised ordinary determiner. This is shown in the following derivation, where a determiner whose phonology is built from the string c is type-raised to the syntactic category \(\mathrm {S|(S|Det)}\), with the corresponding higher-order phonology:

st. The right form of this higher-order phonology of a type-raised determiner can be inferred from the phonological term that is assigned to a syntactically type-raised ordinary determiner. This is shown in the following derivation, where a determiner whose phonology is built from the string c is type-raised to the syntactic category \(\mathrm {S|(S|Det)}\), with the corresponding higher-order phonology:

-

(79)

By replacing the string c with no, we obtain the phonological term in the lexical entry in (78).

We illustrate how this entry is used in the derivation for a simple sentence containing a negative quantifier.

-

(80)

Since the negative determiner is lexically assigned a raised, higher-order type, an ordinary determiner is first hypothesized in the subject position and later gets bound by the negative determiner via hypothetical reasoning with |. Note in particular that the right surface string is obtained by applying the higher-order functional phonology of the negative determiner to its argument of type \(\mathrm {S|Det}\) (an expression missing a determiner).

With this lexical entry for the determiner no, split scope of examples like the following is straightforward.

-

(81)

The company need fire no employee.

As shown in the derivation in (82), by hypothesizing a determiner in the sentence below the modal verb need and binding that hypothesis by a negative determiner above the modal, the desired ¬>need>∃ reading is obtained.

-

(82)

The lexical entry for the conjunction word for determiner gapping can be written as in (83), generalizing the Gapping-type conjunction entry to the \(\mathrm {S|Det|TV}\) type:

-

(83)

Expressions that are of the right type to be coordinated by this conjunction category can be derived via hypothetical reasoning in the usual way:

-

(84)

This is then conjoined with another expression of the same type via the determiner-gapping conjunction in (83) to yield the following coordinated \(\mathrm {S|Det|TV}\):

-

(85)

Note in particular that the right string cat Alpo is obtained for the second conjunct. This is a straightforward result of a couple of β-reduction steps:

-

(86)

The rest of the derivation just involves combining the main verb and the negative determiner with this \(\mathrm {S|Det|TV}\) expression:

-

(87)

The GQ-type entry for the negative quantifier, used in the distributive reading of the negative quantifier in determiner gapping, is obtained from the lexically specified higher-order entry in (78) as follows:

-

(88)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kubota, Y., Levine, R. Gapping as hypothetical reasoning. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 34, 107–156 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9298-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9298-4