Abstract

Regardless of the increased interest in technological innovation in universities, relatively little is known about the technology developed by academic scientists. Long-term analyses of researchers’ technological contribution are notably missing. This paper examines university-based technology in Finland during the period 1900–85. The focus is on the quantity and technological specialization of applications created inside the universities and in the changes that occurred in scientists’ technological output over nine decades. In the long-term analysis several aspects in universities’ technological contribution, which are typically considered a recent phenomenon, turn out to have long historical roots. Thus the empirical evidence provided in the article challenges views emphasising that the world of science has faced a drastic change in recent decades.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

At the end of the period studied here (1985) UH employed around 1,845 teachers and researchers and there were 25,500 students (2010 figures are 3,700 and 35,000). In HUT there were 579 teachers and researchers and 8,700 students (2010 1,900 and 14,000). Since 2010 Helsinki University of Technology has been part of the Aalto University that was formed together with the Helsinki School of Economics and the University of Art and Design Helsinki.

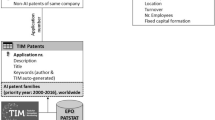

Only scientific personnel is examined and among them only those who had more permanent positions inside the scientific community. Therefore, applications developed by administrative staff and PhD students fall beyond the scope of this article. The focus is on professors, assistant professors, lecturers and adjunct professors working in UH and HUT. All HUT faculties are examined, but from UH only the three where patenting is likely to occur are included: Agriculture and Forestry, Medicine and Mathematics and Science. 1,247 of the researchers worked in UH, 1,020 in HUT and 117 worked in both universities during their academic careers.

The Pate-database includes all Finnish patents for the period 1842–1972 (http://patent.prh.fi/pate/). PatInfo-database provides patent information from the later period (http://patent.prh.fi/patinfo/default2.asp).

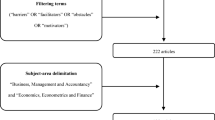

Of these academic patents, 515 were granted during the period 1900–85, on which this article focuses. For more on the definition of the academic patent, see Meyer 2003.

The fact that patenting was more common in HUT is a predictable result. In any university of technology coming from the Technische Hochschule tradition, the basic motive behind teaching and research is detecting and solving technical dilemmas, and the majority of research sectors are potential birthplaces of new technology. In a Humboldtian science university technology is not in a similar central position, and the development of new technology is possible only in some research areas. In the case of the University of Helsinki these were in the faculties of Agriculture and Forestry, Medicine and Mathematics and Science.

An exception is a study by Torkel Wallmark where he analysed the academic patents of the Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden 1945–89. The problem with Wallmark’s study is that he used researcher interviews to collect the patent data and not the actual patent statistics, which impairs the reliability of his results, especially regarding the early years. See Wallmark 1997.

Espacenet; Index of Patents Issued from the United States Patent Office; http://www.uspto.gov/go/stats/univ/org_gr/012_mit_ag.htm. MIT's patents are analysed from the 1960s onwards because MIT appears in the US patent statistics only then. Before that Research Corporation specialising in the university IPR was responsible for the patenting of technology developed in the MIT. (Etzkowitz 1994, 388, 398)

The number of researchers in MIT was calculated from the university’s annual reports and a factual profile leaflet.

Patents by the university adjunct professors who typically worked in industry are not included in the table. The change in the ownership of the immaterial property rights could take place before, during or after the patenting process. It also needs to be kept in mind that technology transfer can occur without changing the ownership of a patent (e.g. licensing).

Among successful innovations is the Orthopantomograph, a dental X-ray developed in UH in the 1950s. Based on this invention, Finnish producers of dental X-ray instruments have had a strong market position until recently. Another example is an ore separator developed in HUT. This instrument made the Otanmäki mines in northern Finland the biggest producer of vanadinium in Europe during the 1970s. An exceptional innovation is the method for preventing hair-loss that sprang up as a by-product of cancer research in UH in the 1970s. Hair care products based on this method (e.g. Helsinki Formula) have generated hundreds of millions of Euros globally.

References

Balconi, Margherita, Stefano Breschi, and Francesco Lissoni. 2004. Networks of inventors and the role of academia: An exploration of Italian patent data. Research Policy 33(1): 127–145.

Etzkowitz, Henry. 2003. Research groups as “quasi-firms”: The invention of the entrepreneurial university. Research Policy 32(1): 109–121.

Etzkowitz, Henry. 1994. Knowledge as property: The Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the debate over academic patent policy. Minerva 32(4): 383–421.

Geuna, Aldo, and Lionel J.J. Nesta. 2006. University patenting and its effects on academic research: The emerging European evidence. Research Policy 35(6): 790–807.

Gibbons, Michael, Camille Limoges, Helga Nowotny, Simon Schwartzman, Peter Scott, and Martin Trow. 1994. The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. London: Sage Publications.

Grupp, Hariolf, and Ulrich Schmoch. 1992. Perceptions of scientification of innovation as measured by referencing between patents and papers: dynamics in science-based fields of technology. In Dynamics of science-based innovation, ed. Hariolf Grupp. Berlin: Springer.

Jones-Evans, Dylan. 1998. Universities, technology transfer and spin-off activities—academic entrepreneurship in different European regions. Targeted socio-economic research project no 1042. Final report. European Union.

Kaataja, Sampsa. 2010. Technology alongside science. Finnish academic scientists as developers of commercial technology during the 20th century. Bidrag till kännedom av Finlands natur och folk. Helsinki. The Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters (In Finnish).

Kutinlahti, Pirjo. 2006. Universities approaching markets. Intertwining scientific and entrepreneurial goals. Espoo/Helsinki. VTT technical research Centre of Finland and University of Helsinki.

Leydesdorff, Loet, and Henry Etzkowitz. 2001. The transformation of university-industry-government relations. Electronic Journal of Sociology 5(4). http://www.sociology.org/content/vol005.004/th.html.

Lissoni, Francesco, Patrick Llerena, Maureen McKelvey, and Bulat Sanditov. 2008. Academic patenting in Europe: New evidence from the KEINS database. Research Evaluation 17(2): 87–102.

Meyer, Martin. 2003. Academic patents as an indicator of useful research? A new approach to measure academic inventiveness. Research Evaluation 12(1): 17–27.

Meyer, Martin, Tanja Siniläinen, Jan Timm Utecht, Olle Persson, Jianzhong Hong. 2003. Tracing knowledge flows in the Finnish innovation system. A study of US patents granted to Finnish university researchers. Technology review 144/2003. Helsinki: Tekes.

Mowery, David, Richard Nelson, Bhaven Sampat, and Arvids Ziedonis. 2004. Ivory tower and industrial innovation. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Mowery, David, and Bhaven Sampat. 2001. Patenting and licensing university inventions: Lessons from the history of the Research Corporation. Industrial and Corporate Change 10(2): 317–355.

Nelson, Richard. 2001. Observations on the post-Bayh-Dole rise of patenting at American universities. Journal of Technology Transfer 26(1–2): 13–19.

OECD. 2003. Turning science into business. Patenting and licensing at public research institutions. Paris: OECD.

Saragossi, Sarina, and Bruno van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie. 2003. What patent data reveal about universities: the case of Belgium. Journal of Technology Transfer 28(1), 47–51.

Schmoch, Ulrich. 1999. Interaction of universities and industrial enterprises in Germany and the United States—a comparison. Industry and Innovation 6(1): 51–68.

Wallmark, J. Torkel. 1997. Inventions and patents at universities: The case of Chalmers University of Technology. Technovation 17(3): 127–139.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaataja, S. University Researchers Contributing to Technology Markets 1900–85. A Long-Term Analysis of Academic Patenting in Finland. Minerva 49, 447–460 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-011-9185-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-011-9185-z