Abstract

This is an invited commentary on five articles on obstetric care in rural Georgia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Significance

This commentary provides historical and contextual perspective on why these five papers on obstetric care in rural Georgia are unique and important and why the work needs to continue and to be expanded to include all OBGYN services.

Urban rural differentials in health and health care are common and due in part to sparsely populated rural areas [1]. But rarely do we get an in-depth look at the problem and potential solutions of providing obstetric care in a large, sparsely populated region. Beginning in 2010, the Georgia Obstetrics and Gynecology Society (GOGS) invited Emory University allied health students to evaluate obstetric care in Georgia where small hospitals had been closing. Dr. Adrienne Zertuche, then a MD MPH student, responded to GOGS’ request by developing and leading an evolving team of over 40 students in a series of studies designed to respond to specific policy concerns. She describes how collaboration between GOGS and Emory University students led to legislative action aimed at improving women’s health [2]. Dr. Bridget Spelke, then a medical student, surveyed all local hospitals outside metropolitan Atlanta to gather data and provide a baseline estimate of the status of current and near future obstetric person power [3].

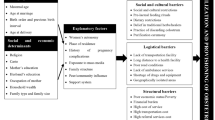

Three public health students conducted research used for their MPH theses. Meredith Pinto recruited and managed six research assistants who interviewed 81 professionals and women who gave birth in last 2 years outside Atlanta. Erika Meyer, one of the research assistants and a fellow MPH student, utilized her surveys to evaluate delays and barriers to prenatal care in rural and peri-urban areas [4]. Meredith Pinto reported on the challenges faced by obstetric service providers [5]. Finally, Elizabeth Smulian surveyed OBGYN residents and midwifery students to evaluate their potential as future clinicians in rural Georgia [6].

Part of the public health success of GMIHRG’s work is that it focused on obstetric care at the local level—an area in which all politicians have a stake. These efforts have characterized the rural obstetric shortage problem and led to an Emory initiative to train midwives in South Georgia. But future work needs to focus further on developing solutions to rural shortages and hospital closures. We need to develop rural health care systems for family planning and maternity resources.

Georgia couples also need effective contraception to facilitate having children when they want them and can afford them. The unique 1995 Georgia Women’s Health Survey of 3130 women reported 53 % of last pregnancies were planned, 29 % mistimed and 17 % unwanted. At that time only 60 % of women aged 15–44 years used contraception and fewer than 2 % were using LARC methods. Virtually all (98 %) young women had sexual intercourse before marriage and 17 % of all women had been forced to have sexual intercourse. Moreover, 44 % of those with no children were using contraception [7].

Historically, the Centers for Disease Control [8] assigned medical epidemiologists to support and evaluate Georgia’s family planning program from 1964 (CDC MMWR) through 1981 (Rochat RW, personal recollection) and stopped doing so only when state priorities shifted away from family planning. Forty-five years ago, Georgia’s family program was so successful that a map of Georgia counties’ family planning services was on the front cover of Family Planning Perspectives [9]. Yet today the Georgia Department of Public Health lacks federal Title X family planning funds and its rural southern citizens are facing potential Zika virus exposure through Aedes aegypti mosquitoes [10]. In response to the Zika epidemic in Puerto Rico, CDC has published estimates for contraceptive needs [11]. Moreover, an important national initiative has begun [12] to provide LARC for postpartum women and Georgia has initiated postpartum LARC services [13]. Few states provide funding for LARC methods postabortion [14].

In summary, the work that GMIHRG has done has been important, low cost, and responsive to an urgent and specific health care problem. But the current assessment of obstetric needs for women in rural Georgia needs to be rapidly expanded to include an assessment of their family planning needs. New studies should explore the effectiveness of the current LARC initiatives for postpartum women and the need to expand LARC services to include non-postpartum women, women receiving emergency Medicaid services, and women immediately after an abortion.

References

Rochat, R. W. (2008). The challenges of conducting research to improve the Health of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12, S126–S127.

Zertuche, A. D., Spelke, B., Julian, Z., Pinto, M., & Rochat R. (2016). Georgia maternal and infant health research group (GMIHRG): Mobilizing allied health students and community partners to put data into action. Maternal and Child Health Journal. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-1996-y.

Spelke, B., Zertuche, A., Julian, Z., & Rochat, R (2016). Obstetric provider maldistribution: Georgia, USA, 2011. Maternal and Child Health Journal. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-1999-8.

Meyer, E., Hennink, M., Rochat, R., Julian, Z., Pinto, M., Zertuche, A., & Spelke, B. (2016). Working towards safe motherhood: Delays and barriers to prenatal care for women in rural and peri-urban areas of Georgia. Maternal and Child Health Journal. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-1997-x.

Pinto, M., Rochat, R., Hennink, M., Zertuche, A., Spelke, B. (2016). Bridging the gaps in obstetric care: Perspectives of service delivery providers on challenges and core components of care in rural Georgia. Maternal and Child Health Journal. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-1995-z.

Smulian, E. A., Zahedi, L., Hurvitz, J., Talbot, A., Williams, A., Julian, Z., Zertuche, A., & Rochat, R. (2016). Obstetric provider trainees in Georgia: Characteristics and attitudes about practice in obstetric provider shortage areas. Maternal and Child Health Journal. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-1998-9.

Serbanescu, F., Rochat, R., Georgia Women’s Health Survey (1995). Preliminary report, 1996, office of perinatal epidemiology, epidemiology and prevention branch, division of public health, Georgia Department of Human Resources, 110 p.

CDC’s 60th Anniversary: Director’s Perspective—Sencer, D. J., M.D., M.P.H., (2006). 1966–1977. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 55(27), 745–749. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr//preview/mmwrhtml/mm5527a2.htm.

Allen, D. T., Rochat, R. W., Murray, M. A., & Tyler, C. W., Jr. (1970). Computer mapping of family planning need and services. Family Planning Perspectives, 2(4), 32–34.

Hotez, P. J. (2016). Zika is coming. NY Times op-ed, April 8.

Tepper, N. K., Goldberg, H. I., Bernal, M. I., et al. (2016). Estimating contraceptive needs and increasing access to contraception in response to the Zika virus disease outbreak—Puerto Rico, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 65, 311–314. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6512.

Kroelinger, C., Waddell, L. F., Addison, D., et al. (2015). Working with state health departments on emerging issues in maternal and child health: Immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraceptives. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(9), 693–701.

Brown, P., Csukas, S., Burnett, C., & Kottke, M. (2014). Postpartum LARC. Presented at ASTHO LARC meeting. http://www.astho.org/Georgia-LARC-Presentation/.

http://larcprogram.ucsf.edu/immediate-post-abortion. Accessed May 1 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rochat, R.W. Commentary on Obstetric Care in Rural Georgia. Matern Child Health J 20, 1321–1322 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2024-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2024-y